Introduction

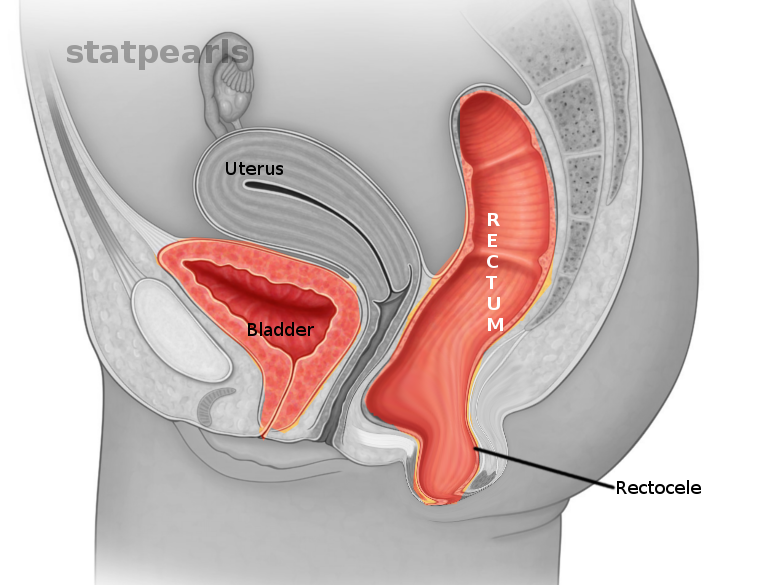

Rectocele is a variety of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) that involves the herniation of the rectum through the rectovaginal septum into the posterior vaginal lumen.

Anatomically, the vagina begins at the hymenal ring and terminates at the cervix. The bladder lies anterior to the vagina, while the rectum lies posterior to the vagina. The vagina has support at three levels. Most superiorly, it is supported by the uterosacral ligament complex. While in the middle, it is supported by the levator ani muscles, and by the endopelvic fascia in the lower segments. The vaginal wall tissue is composed of multiple layers. The innermost tissue layer is a nonkeratinized squamous epithelium, then stroma consisting of collagen and elastic tissue, and the outermost tissue layer is a smooth muscle and collagen layer.[1]

The rectovaginal septum connects to the endopelvic fascia at the level of the perineal body. The loss of integrity in the rectovaginal fascia would result in a herniation of the rectal tissue into the vaginal lumen, and vice versa, leading to a vaginal bulge along the posterior vaginal wall on examination that would become more pronounced with the Valsalva maneuver.[1]

These herniations are also associated with enteroceles, or herniation of bowel into the vaginal lumen if there is a separation of the fascia from the vaginal cuff. Many women have an anatomic presence of pelvic organ prolapse. It is present in two-thirds of parous women.[2] However, not all women who have a rectocele found on the examination will be symptomatic. Over time, as the defect becomes larger, women can become symptomatic. The symptoms include vaginal bulge, obstructive defecation, constipation, and perineal pressure.[3] As the bulge becomes larger, it can become exteriorized - meaning that the bulge is outside the level of the hymen. The mucosa becomes exposed to the outside environment; it is at risk for erosion and bleeding.[3]

The management of this condition largely depends on the extent of the prolapse and the severity of the symptoms. Management options include lifestyle changes, medications, pessaries, and surgery.[4][5][6]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The posterior vaginal wall is supported by uterosacral ligament complex superiorly, levator ani muscles in the middle, and by the endopelvic fascia in the lower segments. The rectovaginal septum is attached to the endopelvic fascia at the level of the perineal body and runs between the vagina and rectum. The loss of integrity in this septum would result in a herniation of the rectal tissue into the vaginal lumen resulting in a vaginal bulge on examination. Many factors play a role in the loss of integrity of the rectovaginal septum, including non-modifiable and modifiable factors.[7]

Non-modifiable risk factors: e.g., advanced age and genetics.

Modifiable risk factors: These include greater parity, history of vaginal delivery, history of pelvic surgery, obesity, level of education, constipation, and conditions that increase intra-abdominal pressure chronically such as COPD or a chronic cough.

Age, BMI, parity, and vaginal delivery are the most well-documented risk factors.[8][9]

Epidemiology

The incidence and prevalence of all pelvic organ prolapse are unknown because many patients are asymptomatic and do not seek out medical care for their prolapse. Another reason for unknown prevalence is the lack of a comprehensive classification system for rectoceles. For pelvic organ prolapse in general, the incidence is around 67% of parous women.[2] About 11.1% of women by the age of 80 years have undergone surgical intervention for pelvic organ prolapse.[10]

Pathophysiology

A rectocele occurs when healthy rectovaginal septal tissue loses integrity, and the rectum herniates through into the vaginal lumen. Loss of integrity can happen in a variety of ways, including childbirth, age-related connective tissue changes, and increased stress on the tissue through straining or obesity. A patient may have one or many of these issues, as they can be additive.[11] The most common findings of rectocele when symptomatic are a vaginal bulge from the herniation of tissue, pelvic pressure, and changes in defecation.

History and Physical

History:

Rectoceles have a broad range of symptoms. Some patients may present as asymptomatic while others may demonstrate a significant impact on the quality of life, including the following symptoms[3]:

- Pelvic pain/pressure

- Posterior vaginal bulge

- Obstructive defecation

- Incomplete defecation

- Constipation

- Dyspareunia

- Erosions and bleeding of mucosa if there is tissue exposure to the outside environment

Physical Exam:

A thorough examination will include a vaginal exam, rectal exam, abdominal exam, and focused neurological exam.

The focused neurological exam consists of levator ani muscle tone and contraction strength.

The vaginal exam can be evaluated using the Baden-Walker or POP-Q exam. The Baden-Walker system utilizes one measurement. The distance of the most distal portion of the prolapse from the hymen while the patient is completing the Valsalva maneuver.[12] The grades are:

- Grade 0 - normal position

- Grade 1 - Descent halfway to the hymen

- Grade 2 - Descent to the hymen

- Grade 3 - Descent halfway past the hymen

- Grade 4 - Descent is as far as possible past the hymen

The POP-Q system involves taking several measurements and is more complex, but it is highly reliable. The posterior points Ap and Bp are the measurements needed to determine the severity of the rectocele.[13]

- TVL: total vaginal length after reducing the prolapse

- Gh: Genital hiatus length

- Pb: perineal body length

- Ap: A Point on the posterior vaginal wall that is 3 cm proximal to the hymen

- Bp: A point that is the most distal position of the remaining upper posterior vaginal wall

- C: Cervical depth

- D: Posterior fornix depth (only in patients with a uterus)

- Aa: anterior point analogous to Ap

- Ba: anterior point analogous to Bp

These points are measured while the patient is performing the Valsalva maneuver. The range of values for the Ap and Bp points, which are important for rectocele measurement, is -3 cm to +3 cm for the Ap point and -3cm to +tvl length in the Bp point. The POP-Q staging criteria are[13]:

- Stage 0: Ap, Bp at the leading edge (X) = -3 cm

- Stage I: X less than -1 cm

- Stage II: -1 cm less than X less than +1 cm

- Stage III: +1 cm less than X less than +(TVL-2) cm

- Stage IV: X greater than +(TVL-2) cm

Evaluation

Evaluation of a rectocele is determined mainly by the clinical exam. Other laboratory tests and radiographic tests are generally not necessary.

A special test that can be done to confirm a rectocele is defecography. The patient will have contrast medium instilled in the vagina, bladder, and rectum. Using a special commode, the patient will be instructed to defecate while the X-ray is taken. This test can be useful to determine the size of the rectocele, larger than 2 cm is considered abnormal.[14]

Urodynamic studies can be helpful in patients with rectocele and complex voiding issues. If a patient is receiving surgery, it may be useful to determine if the patient has urinary incontinence with the prolapse reduced. If there is incontinence with reduction with prolapse, it may be helpful to include a procedure to prevent urinary incontinence in the plan.[15]

Another useful diagnostic tool for surgical planning is dynamic MRI (DMRI) which provides visualization of the rectocele and movements of the pelvic floor.[11] DMRI is a valuable adjunct test when a patient's symptoms are more significant than the physical examination findings suggest. Its use for preoperative planning has made it more widespread.[16]

Treatment / Management

The severity of the patient's symptomatology dictates the management approach to rectocele.

Conservative medical management of rectoceles begins with behavioral modifications. A high fiber diet and increased water intake to reduce constipation/defecatory symptoms may be enough to improve the patient’s quality of life. The patient should be drinking at least 2 to 3 liters of nonalcoholic, noncaffeinated fluids daily. The patient can also begin performing Kegel exercises and may benefit from the supervision of a pelvic floor physiotherapist.[4][6]

When the conservative treatment is unsuccessful, the next step is the use of a vaginal pessary. The vaginal pessaries come in different shapes and sizes. Therefore, fitting the patient with a pessary will come with a little trial and error. The function of this device is to stabilize the defects in the pelvic floor while also managing any other issues, such as cystoceles and prolapse of other organs.[5] Pessaries have been used to manage pelvic organ prolapse since Hippocrates when he used a halved pomegranate to treat prolapse.[17] Currently, there are a variety of devices used which differ in shape and size, made of medical-grade silicone. One of the most common shapes is the ring support pessary. Risk factors for pessary failure include large genital hiatus, short vaginal length, and prior pelvic organ prolapse surgery.[17] If the pessary cannot be manually inserted, then it may be inserted under anesthesia, or it may not be a treatment option for the patient. The most common complications from pessary use include vaginal discharge, vaginal bleeding, and odor.[17] There is little evidence on how often a pessary cleaning and changing should be performed.[18] However, teaching the patient how to remove and clean the pessary will increase the patient's bodily autonomy.[17](B2)

Surgical management is reserved for those with obstructive defecatory symptoms and bothersome symptoms who have failed other forms of treatment.[19] The principle of the surgical treatment is posterior vaginal wall or fibromuscular tissue repair or plication to strengthen the tissue and reduce the prolapsing rectum through the posterior vaginal wall. There are different surgical approaches to rectocele repair. These approaches include the vaginal approach, the abdominal approach, and the rectal approach. There is no consensus on the best approach or the best surgical repair for treating rectoceles.[20] Many factors contribute to determining which procedure would work best for the patient. These include age, vaginal length, desire for coitus, stage of prolapse, and symptoms of bowel dysfunction.[20][21] Urogynecologists generally perform vaginal and abdominal procedures, and colorectal surgeons generally perform transrectal procedures.[20] Traditionally, the posterior colporrhaphy with transvaginal access is the preferred approach to rectocele repair. In this procedure, the surgeon cuts the vaginal mucosa from the perineal body toward vaginal apex along the posterior wall. The vaginal lumen is then bluntly dissected from the rectovaginal septum. Then the fibromuscular tissue is plicated along the midline with sutures to increase the integrity of the rectovaginal fistula. Any areas of weakness are often plicated as well. After plication, the incision through the vaginal mucosa gets closed, with excision of redundant tissue. Several studies suggest a perineoplasty to avoid perineal rectocele.[22] There are proposals to use mesh as a method to strengthen the plication of fibromuscular tissue; however, recent studies have found no difference in failure rates in procedures that used mesh and those who did not.[23][24] For posterior colporrhaphy, rate of anatomic failure is 8.6% without mesh and 11.9% with graft.[24](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

While the condition will be very apparent on physical exam, some conditions may have similar symptoms. The differential diagnosis for these symptoms includes rectocele, rectal prolapse, enterocele, and sigmoidocele.[25]

Prognosis

Rectoceles and other types of pelvic organ prolapse have a good prognosis as they are not life-threatening conditions. They affect the patient’s quality of life. Baden-Walker type I prolapse has an annual regression rate of 22% per 100-woman years. Baden-Walker types II and III, a lower regression rate. Increased parity correlates with increased progression rates for rectoceles.[26]

Complications

Lifestyle changes and pelvic floor physical therapy have a minimal risk for complications. Pessaries have a slightly increased risk of ulceration as a complication if not cared for properly.[5]

Surgery bears the highest potential for complications. Outside of the regular risk for surgery (bleeding, infection, etc.), complications vary depending on the type of surgery and whether the surgeon used a mesh. Mesh can erode the tissue. The most significant complication that can occur post-surgically is the risk of recurrent prolapse.

When using transvaginal mesh repair, there has been found to be a higher reoperation rate (11%) in comparison to native tissue repair (3.7%). Posterior vaginal repairs have less recurrent prolapse symptoms and lower recurrence on a physical exam than transanal repairs.[27]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Both the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS) and the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) have patient fact sheets that clinicians can give to patients suffering from rectoceles. ASCRS has patient education videos for many conditions, including pelvic floor dysfunction, which can be helpful with educating the patient on their rectocele.

There is a commercially available pelvic prolapse quantification tool where a physician can input the patient’s measurements, and the software creates a model with the patient’s anatomy. This tool is useful in explaining the severity of the rectocele to the patient. The patient education handouts provided with the tool also include a pessary care handout, which would be necessary for patients electing to use pessaries for their treatment.[28]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Rectoceles may be benign but have enormous morbidity. The disorder is underdiagnosed and undertreated. For this reason, management is best when performed by an interprofessional team. Rectoceles are not well studied because many patients are either asymptomatic or do not seek care for their symptoms. While the gynecologist is usually the physician who makes the initial exam finding and is involved in the care of patients with a rectocele, it is essential to consult with an interprofessional team of specialists that include a colorectal surgeon and urogynecologist. Since these patients have conditions of a complex nature involving the genital and gastrointestinal systems, an interprofessional team would be optimal for the management of rectoceles.[29] [Level II] A wound care nurse should educate the patient on the management of the prolapsed rectocele and what complications may occur; these need to be shared with the treating physician and the rest of the team. Pelvic floor physiotherapists and nurses are also essential members of the interprofessional group as they are necessary for the promotion of pelvic health for patients with pelvic floor disorders.[30] [Level II] Before performing surgery, the patient must receive education to set realistic expectations, and informed consent is vital.

As demonstrated above, the treatment of rectocele requires the collaboration of an interprofessional team with each discipline contributing from their area of expertise but communicating actions and findings to all members of the team to drive positive outcomes. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

This sagitall image from MR Defecography shows severe perineal descent syndrome involving the posterior compartment. Also note the moderate to severe anterior rectocele. No intrarectal intuscusseption or internal prolapse was seen. This image also demonstrates how all the measurements are performed. Contributed by Nishant Gupta, MD

References

Beck DE, Allen NL. Rectocele. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery. 2010 Jun:23(2):90-8. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1254295. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21629626]

Bump RC, Norton PA. Epidemiology and natural history of pelvic floor dysfunction. Obstetrics and gynecology clinics of North America. 1998 Dec:25(4):723-46 [PubMed PMID: 9921553]

Iglesia CB, Smithling KR. Pelvic Organ Prolapse. American family physician. 2017 Aug 1:96(3):179-185 [PubMed PMID: 28762694]

Berman L, Aversa J, Abir F, Longo WE. Management of disorders of the posterior pelvic floor. The Yale journal of biology and medicine. 2005 Jul:78(4):211-21 [PubMed PMID: 16720016]

Bash KL. Review of vaginal pessaries. Obstetrical & gynecological survey. 2000 Jul:55(7):455-60 [PubMed PMID: 10885651]

Tso C, Lee W, Austin-Ketch T, Winkler H, Zitkus B. Nonsurgical Treatment Options for Women With Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Nursing for women's health. 2018 Jun:22(3):228-239. doi: 10.1016/j.nwh.2018.03.007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29885711]

Vergeldt TF, Weemhoff M, IntHout J, Kluivers KB. Risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse and its recurrence: a systematic review. International urogynecology journal. 2015 Nov:26(11):1559-73. doi: 10.1007/s00192-015-2695-8. Epub 2015 May 13 [PubMed PMID: 25966804]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNygaard I, Bradley C, Brandt D, Women's Health Initiative. Pelvic organ prolapse in older women: prevalence and risk factors. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2004 Sep:104(3):489-97 [PubMed PMID: 15339758]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGlazener C, Elders A, MacArthur C, Lancashire RJ, Herbison P, Hagen S, Dean N, Bain C, Toozs-Hobson P, Richardson K, McDonald A, McPherson G, Wilson D, ProLong Study Group. Childbirth and prolapse: long-term associations with the symptoms and objective measurement of pelvic organ prolapse. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2013 Jan:120(2):161-168. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12075. Epub 2012 Nov 27 [PubMed PMID: 23190018]

Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1997 Apr:89(4):501-6 [PubMed PMID: 9083302]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePatcharatrakul T, Rao SSC. Update on the Pathophysiology and Management of Anorectal Disorders. Gut and liver. 2018 Jul 15:12(4):375-384. doi: 10.5009/gnl17172. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29050194]

Baden WF, Walker TA. Genesis of the vaginal profile: a correlated classification of vaginal relaxation. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 1972 Dec:15(4):1048-54 [PubMed PMID: 4649139]

Boyd SS, O'Sullivan D, Tulikangas P. Use of the Pelvic Organ Quantification System (POP-Q) in published articles of peer-reviewed journals. International urogynecology journal. 2017 Nov:28(11):1719-1723. doi: 10.1007/s00192-017-3336-1. Epub 2017 Apr 29 [PubMed PMID: 28456821]

Palmer SL, Lalwani N, Bahrami S, Scholz F. Dynamic fluoroscopic defecography: updates on rationale, technique, and interpretation from the Society of Abdominal Radiology Pelvic Floor Disease Focus Panel. Abdominal radiology (New York). 2021 Apr:46(4):1312-1322. doi: 10.1007/s00261-019-02169-y. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31375862]

Adelowo A, Dessie S, Rosenblatt PL. The role of preoperative urodynamics in urogynecologic procedures. Journal of minimally invasive gynecology. 2014 Mar-Apr:21(2):217-22. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2013.10.002. Epub 2013 Oct 18 [PubMed PMID: 24144925]

Gupta AP, Pandya PR, Nguyen ML, Fashokun T, Macura KJ. Use of Dynamic MRI of the Pelvic Floor in the Assessment of Anterior Compartment Disorders. Current urology reports. 2018 Nov 13:19(12):112. doi: 10.1007/s11934-018-0862-4. Epub 2018 Nov 13 [PubMed PMID: 30421087]

Lamers BH, Broekman BM, Milani AL. Pessary treatment for pelvic organ prolapse and health-related quality of life: a review. International urogynecology journal. 2011 Jun:22(6):637-44. doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1390-7. Epub 2011 Apr 7 [PubMed PMID: 21472447]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHanson LA, Schulz JA, Flood CG, Cooley B, Tam F. Vaginal pessaries in managing women with pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence: patient characteristics and factors contributing to success. International urogynecology journal and pelvic floor dysfunction. 2006 Feb:17(2):155-9 [PubMed PMID: 16044204]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHall GM, Shanmugan S, Nobel T, Paspulati R, Delaney CP, Reynolds HL, Stein SL, Champagne BJ. Symptomatic rectocele: what are the indications for repair? American journal of surgery. 2014 Mar:207(3):375-9; discussion 378-9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.12.002. Epub 2013 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 24444857]

Barbalat Y, Tunuguntla HS. Surgery for pelvic organ prolapse: a historical perspective. Current urology reports. 2012 Jun:13(3):256-61. doi: 10.1007/s11934-012-0249-x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22528116]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTasev V, Todorov R, Taseva A. RECTOCELE - A LITERATURE REVIEW WITH A CASE REPORT. Khirurgiia. 2015:81(1):34-7 [PubMed PMID: 26506638]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMustain WC. Functional Disorders: Rectocele. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery. 2017 Feb:30(1):63-75. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1593425. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28144214]

Sand PK, Koduri S, Lobel RW, Winkler HA, Tomezsko J, Culligan PJ, Goldberg R. Prospective randomized trial of polyglactin 910 mesh to prevent recurrence of cystoceles and rectoceles. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2001 Jun:184(7):1357-62; discussion 1362-4 [PubMed PMID: 11408853]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSung VW, Rardin CR, Raker CA, Lasala CA, Myers DL. Porcine subintestinal submucosal graft augmentation for rectocele repair: a randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2012 Jan:119(1):125-33. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823d407e. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22183220]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchwandner O, Poschenrieder F, Gehl HB, Bruch HP. [Differential diagnosis in descending perineum syndrome]. Der Chirurg; Zeitschrift fur alle Gebiete der operativen Medizen. 2004 Sep:75(9):850-60 [PubMed PMID: 15258747]

Handa VL, Garrett E, Hendrix S, Gold E, Robbins J. Progression and remission of pelvic organ prolapse: a longitudinal study of menopausal women. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2004 Jan:190(1):27-32 [PubMed PMID: 14749630]

Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Schmid C. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2013 Apr 30:(4):CD004014. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004014.pub5. Epub 2013 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 23633316]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMurray C, Thomas E, Pollock W. Vaginal pessaries: can an educational brochure help patients to better understand their care? Journal of clinical nursing. 2017 Jan:26(1-2):140-147. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13408. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27239963]

Pandeva I, Biers S, Pradhan A, Verma V, Slack M, Thiruchelvam N. The impact of pelvic floor multidisciplinary team on patient management: the experience of a tertiary unit. Journal of multidisciplinary healthcare. 2019:12():205-210. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S186847. Epub 2019 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 30936714]

Dufour S, Hondronicols A, Flanigan K. Enhancing Pelvic Health: Optimizing the Services Provided by Primary Health Care Teams in Ontario by Integrating Physiotherapists. Physiotherapy Canada. Physiotherapie Canada. 2019 Spring:71(2):168-175. doi: 10.3138/ptc.2017-81.pc. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31040512]