Introduction

Calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease (CPPD) is a crystal deposition arthropathy involving the synovial and periarticular tissues.[1] Its clinical presentation may range from being asymptomatic to acute or chronic inflammatory arthritis.[2]

Different terms are used to describe the varied phenotypes of calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease.[1] Acute calcium pyrophosphate (CPP) deposition arthritis, frequently referred to as “pseudogout,” presents as an acute flare of synovitis that resembles acute urate arthropathy (gout). Chronic CPP deposition arthritis informally referred to as pseudo-rheumatoid arthritis may present with a waxing and waning clinical course that may last for several months and resemble rheumatoid arthritis involving the wrists and metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints.[1] The term chondrocalcinosis describes the characteristic radiological finding of intraarticular fibrocartilage calcification.[3]

The crystals involved in calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease are composed of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate and commonly affect larger and weight-bearing joints, including the hips, knees, or shoulders.[2] A large number of patients present with underlying joint disease or metabolic abnormalities predisposing to CPP deposition, including osteoarthritis, trauma, surgery, or rheumatoid arthritis.[3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease is believed to be caused by an imbalance between the production of pyrophosphate and the levels of pyrophosphatases in diseased cartilage. As pyrophosphate deposits in the synovium and adjacent tissues, it combines with calcium to form CPP.[4]

Several comorbidities have correlations with CPPD. In a number of studies, hyperparathyroidism presented the highest positive association with CPPD, followed by gout, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and hemochromatosis. Other comorbidities associated with it include osteoporosis, hypomagnesemia, chronic kidney disease, and calcium supplementation.[5][6][7][8]

Deposition of calcium pyrophosphate is believed to cause activation of the immune system producing inflammation and further soft tissue injury.[9]

Epidemiology

Most patients affected by acute calcium pyrophosphate deposition arthritis are over the age of 65. Thirty to fifty percent of patients present over the age of 85 years.[4] A cross-sectional study involving 2,157 cases of CPPD in US veterans reported a point prevalence of 5.2 per 1000, with an average age of 68 years and 95% of male prevalence.[5] CPPD rarely presents in patients under the age of 60.[10]

A large cross-sectional study reported a 4 % crude prevalence of radiographic chondrocalcinosis in the general population.[10]

History and Physical

In patients presenting with acute calcium pyrophosphate arthritis, manifestations are similar to acute urate arthropathy with joint edema, erythema, and tenderness.[3] Up to 50% of these patients may also present with a low-grade fever.[1] The most commonly affected joint is the knee, but other weight-bearing joints may also be affected, including the hips and shoulders.[11]

A subset of patients present with chronic CPP arthritis, often with waxing and waning episodes of non-synchronous, inflammatory arthritis affecting multiple non-weight bearing joints such as wrists and MCP joints, resembling rheumatoid arthritis.[1]

Clinicians should suspect crystal deposition disease in elderly patients presenting with acute degenerative arthritis in weight-bearing joints.[9] The elderly population will commonly run a milder course.[12] Some patients will present acute flares after traumatic injuries.[4]

Evaluation

After an appropriate physical examination, patients suspected to have calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease should undergo arthrocentesis for synovial fluid analysis, in addition to radiography of the involved joints.[13]

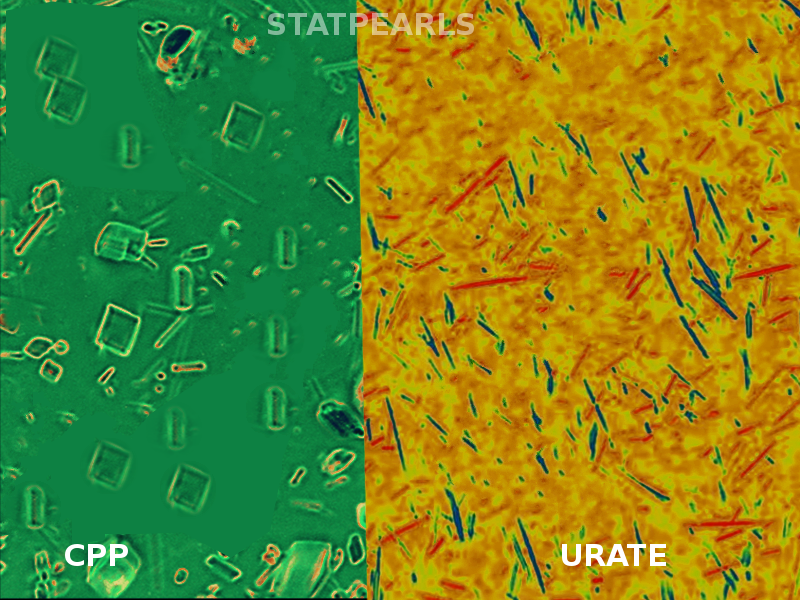

Diagnostic confirmation may be via the presence of rhomboid crystals in the synovial fluid aspirate visualized under polarized microscopy. These crystals typically present positive birefringence.[4]

While imaging findings consistent with chondrocalcinosis support the diagnosis of CPPD, its absence does not rule it out.[14] Early signs may be evidenced through ultrasound (US) as cartilage abnormalities. Joint cartilage calcification, known as chondrocalcinosis, may be visualized through radiographic imaging.[9][14][15]

Previous studies have demonstrated the usefulness of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), particularly gradient-echo sequences, for the evaluation of calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposition burden in joint cartilage.[16]

Treatment / Management

The treatment for patients with calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease is based on decreasing inflammation and stabilizing any underlying metabolic disease that may predispose them to calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposition. In patients with acute flares, with the involvement of one or two joints, the treatment of choice is usually joint aspiration and intra-articular glucocorticoid administration, unless contraindicated.[4][17]

For patients presenting with acute inflammation involving three or more joints, the treatment is typically systemic, often with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Patients with contraindications for NSAIDs may receive treatment with colchicine or systemic glucocorticoids.[1]

Corticosteroid injection should only be performed after septic arthritis has been ruled out or considered unlikely. In patients presenting with signs and symptoms suggestive of septic arthritis, the recommendation is to defer glucocorticoid administration until synovial fluid cultures are negative.[1][4]

Other measures include the application of ice packs and joint rest with restriction of weight-bearing to decrease further inflammation. Patients with recurrent episodes of acute CPP arthritis may receive daily low-dose colchicine.[4]

While several medications decrease serum urate levels and prevent urate crystal formation, there is no current therapy directly targeting CPP crystal deposition. Hence, the treatment of CPPD relies on treating predisposing metabolic diseases, soft tissue inflammation, and symptomatology.[9]

Differential Diagnosis

As discussed above, calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease has different phenotypes. Therefore, the differential diagnosis should be based on the clinical presentation and may include gout, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and erosive osteoarthritis.[4]

The intra-articular radiological calcification seen in patients with CPPD is characteristic. In knee x-rays, chondrocalcinosis presents as a thin dense intraarticular opacification that runs parallel and separated from the bone cortex or as a calcifying opacification in the menisci.[12][15]

Diagnosis of CPPD is presumed in patients with symptomatic joint disease who present the characteristic radiological findings of chondrocalcinosis.[12] As discussed, several imaging modalities may present characteristic findings of CPPD, including x-ray, US, or MRI.[9] When needed, a definite diagnosis is achieved by polarizing light microscopy of synovial fluid, showing the presence of CPP crystals.[12][15]

Prognosis

Acute calcium pyrophosphate arthritis is generally self-limited, and the inflammation usually resolves within days to weeks of treatment.[1]

Patients with chronic CPP inflammatory arthritis may present overlapping manifestations with rheumatoid arthritis, such as morning stiffness, localized edema, and decreased range of motion. Some patients also present tenosynovitis with carpal or cubital tunnel syndrome.[11] Multiple joints are commonly involved, and the episodes of inflammation may present in a nonsynchronous, waxing, and waning clinical course lasting several months.[7][8]

Patients with underlying joint comorbidities, such as osteoarthritis, have an increased risk for acute CPP arthritis. When deposited, CPP crystals activate the immune system, promoting inflammation and fibrocartilage injury.[1]

Complications

The molecular structure of calcium pyrophosphate has the potential of triggering inflammatory responses.[9] The presence of chondrocalcinosis has associations with the degradation of menisci and synovial tissue.[16]

Rarely, patients may present with palpable nodules or masses that resemble gout tophi after several episodes of acute CPP crystal arthritis. These nodules localize in the periarticular tissue and represent CPP crystal accumulations within the synovium and adjacent soft tissue; they may lead to further degradation of the affected joint.[18]

A subset of patients may present with spinal involvement, occasionally causing clinical manifestations such as spine stiffness and bony ankylosis resembling ankylosing spondylitis. Some individuals may have clinical manifestations similar to diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) with calcification of the posterior longitudinal ligament leading to spinal cord compression symptoms.[19][20]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with chondrocalcinosis or previous episodes of acute calcium pyrophosphate arthritis will benefit from knowing that certain conditions carry associations with arthritic flares, including surgical procedures or trauma.[4] Individuals who present at a younger age with CPPD may receive screening for underlying metabolic abnormalities such as hyperparathyroidism or hemochromatosis. Obtaining an adequate family history is also necessary.[21]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Chondrocalcinosis is a relatively common imaging finding in asymptomatic patients. Studies have described a higher prevalence of these findings in late adulthood without gender predilection.[22] Furthermore, although chondrocalcinosis correlates with osteoarthritis, studies suggest that the risk of both diseases increases independently with age, meaning that chondrocalcinosis may develop without osteoarthritis.[23] Asymptomatic older patients may not require further workup or therapy for an isolated finding of chondrocalcinosis.

Due to a broad range of clinical manifestations, calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease should be considered in patients presenting with signs and symptoms suggestive of rheumatoid arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis.[24]

A number of specialists use the high-resolution US in the evaluation of patients with crystal arthropathies, as it may provide useful findings to help differentiate CPPD from other conditions such as gout. Chondrocalcinosis presents earlier in the US than in plain films. This modality may also find use in patients with symptomatic arthropathies of unclear etiology, or with inconclusive results in the fluid aspirate. Additionally, it could potentially decrease the need for using more expensive imaging modalities such as MRI.[16][25][26]

Media

References

Rosales-Alexander JL, Balsalobre Aznar J, Magro-Checa C. Calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposition disease: diagnosis and treatment. Open access rheumatology : research and reviews. 2014:6():39-47 [PubMed PMID: 27790033]

Bencardino JT, Hassankhani A. Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition disease. Seminars in musculoskeletal radiology. 2003 Sep:7(3):175-85 [PubMed PMID: 14593559]

Abhishek A. Calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease: a review of epidemiologic findings. Current opinion in rheumatology. 2016 Mar:28(2):133-9. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000246. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26626724]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHiggins PA. Gout and pseudogout. JAAPA : official journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants. 2016 Mar:29(3):50-2. doi: 10.1097/01.JAA.0000475472.40251.58. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26914781]

Kleiber Balderrama C, Rosenthal AK, Lans D, Singh JA, Bartels CM. Calcium Pyrophosphate Deposition Disease and Associated Medical Comorbidities: A National Cross-Sectional Study of US Veterans. Arthritis care & research. 2017 Sep:69(9):1400-1406. doi: 10.1002/acr.23160. Epub 2017 Aug 8 [PubMed PMID: 27898996]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGalozzi P, Oliviero F, Frallonardo P, Favero M, Hoxha A, Scanu A, Lorenzin M, Ortolan A, Punzi L, Ramonda R. The prevalence of monosodium urate and calcium pyrophosphate crystals in synovial fluid from wrist and finger joints. Rheumatology international. 2016 Mar:36(3):443-6. doi: 10.1007/s00296-015-3376-0. Epub 2015 Oct 6 [PubMed PMID: 26440935]

Gerster JC, Varisco PA, Kern J, Dudler J, So AK. CPPD crystal deposition disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clinical rheumatology. 2006 Jul:25(4):468-9 [PubMed PMID: 16365684]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTheiler G, Quehenberger F, Rainer F, Neubauer M, Stettin M, Robier C. The detection of calcium pyrophosphate crystals in the synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis using the cytospin technique: prevalence and clinical correlation. Rheumatology international. 2014 Jan:34(1):137-9. doi: 10.1007/s00296-012-2608-9. Epub 2012 Dec 27 [PubMed PMID: 23269567]

Tausche AK, Aringer M. [Chondrocalcinosis due to calcium pyrophosphate deposition (CPPD). From incidental radiographic findings to CPPD crystal arthritis]. Zeitschrift fur Rheumatologie. 2014 May:73(4):349-57; quiz 358-9. doi: 10.1007/s00393-014-1364-5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24811359]

Neame RL, Carr AJ, Muir K, Doherty M. UK community prevalence of knee chondrocalcinosis: evidence that correlation with osteoarthritis is through a shared association with osteophyte. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2003 Jun:62(6):513-8 [PubMed PMID: 12759286]

Yamamura M. Acute CPP Crystal Arthritis Causing Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan). 2018 Oct 1:57(19):2767-2768. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.0791-18. Epub 2018 May 18 [PubMed PMID: 29780133]

MUNDAY MC. PSEUDOGOUT. British medical journal. 1964 Oct 10:2(5414):889-90 [PubMed PMID: 14185646]

Becker JA, Daily JP, Pohlgeers KM. Acute Monoarthritis: Diagnosis in Adults. American family physician. 2016 Nov 15:94(10):810-816 [PubMed PMID: 27929277]

Zhang W, Doherty M, Bardin T, Barskova V, Guerne PA, Jansen TL, Leeb BF, Perez-Ruiz F, Pimentao J, Punzi L, Richette P, Sivera F, Uhlig T, Watt I, Pascual E. European League Against Rheumatism recommendations for calcium pyrophosphate deposition. Part I: terminology and diagnosis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2011 Apr:70(4):563-70. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.139105. Epub 2011 Jan 7 [PubMed PMID: 21216817]

Schlee S, Bollheimer LC, Bertsch T, Sieber CC, Härle P. Crystal arthritides - gout and calcium pyrophosphate arthritis : Part 2: clinical features, diagnosis and differential diagnostics. Zeitschrift fur Gerontologie und Geriatrie. 2018 Jul:51(5):579-584. doi: 10.1007/s00391-017-1198-2. Epub 2017 Feb 23 [PubMed PMID: 28233118]

Gersing AS, Schwaiger BJ, Heilmeier U, Joseph GB, Facchetti L, Kretzschmar M, Lynch JA, McCulloch CE, Nevitt MC, Steinbach LS, Link TM. Evaluation of Chondrocalcinosis and Associated Knee Joint Degeneration Using MR Imaging: Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. European radiology. 2017 Jun:27(6):2497-2506. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4608-8. Epub 2016 Oct 4 [PubMed PMID: 27704199]

Sidari A, Hill E. Diagnosis and Treatment of Gout and Pseudogout for Everyday Practice. Primary care. 2018 Jun:45(2):213-236. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2018.02.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29759121]

Shen G, Su M, Liu B, Kuang A. A Case of Tophaceous Pseudogout on 18F-FDG PET/CT Imaging. Clinical nuclear medicine. 2019 Feb:44(2):e98-e100. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000002308. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30325826]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMuthukumar N, Karuppaswamy U. Tumoral calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease of the ligamentum flavum. Neurosurgery. 2003 Jul:53(1):103-8; discussion 108-9 [PubMed PMID: 12823879]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYayama T, Kobayashi S, Sato R, Uchida K, Kokubo Y, Nakajima H, Takamura T, Mwaka E, Orwotho N, Baba H. Calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposition in the ligamentum flavum of degenerated lumbar spine: histopathological and immunohistological findings. Clinical rheumatology. 2008 May:27(5):597-604 [PubMed PMID: 17934688]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAbhishek A, Doherty M. Update on calcium pyrophosphate deposition. Clinical and experimental rheumatology. 2016 Jul-Aug:34(4 Suppl 98):32-8 [PubMed PMID: 27586801]

Stensby JD, Lawrence DA, Patrie JT, Gaskin CM. Prevalence of asymptomatic chondrocalcinosis in the pelvis. Skeletal radiology. 2016 Jul:45(7):949-54. doi: 10.1007/s00256-016-2376-9. Epub 2016 Apr 2 [PubMed PMID: 27037810]

Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Naimark A, Kannel W, Meenan RF. The prevalence of chondrocalcinosis in the elderly and its association with knee osteoarthritis: the Framingham Study. The Journal of rheumatology. 1989 Sep:16(9):1241-5 [PubMed PMID: 2810282]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMoshrif A, Laredo JD, Bassiouni H, Abdelkareem M, Richette P, Rigon MR, Bardin T. Spinal involvement with calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease in an academic rheumatology center: A series of 37 patients. Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism. 2019 Jun:48(6):1113-1126. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.10.009. Epub 2018 Oct 14 [PubMed PMID: 30415946]

Grassi W, Okano T, Filippucci E. Use of ultrasound for diagnosis and monitoring of outcomes in crystal arthropathies. Current opinion in rheumatology. 2015 Mar:27(2):147-55. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000142. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25633243]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFilippucci E, Di Geso L, Girolimetti R, Grassi W. Ultrasound in crystal-related arthritis. Clinical and experimental rheumatology. 2014 Jan-Feb:32(1 Suppl 80):S42-7 [PubMed PMID: 24528621]