Introduction

Asthma is a prevalent chronic inflammatory respiratory condition affecting millions of people worldwide and presents substantial challenges in both diagnosis and management. This respiratory condition is characterized by inflammation of the airways, causing intermittent airflow obstruction and bronchial hyperresponsiveness. The hallmark asthma symptoms include coughing, wheezing, and shortness of breath, which can be frequently exacerbated by triggers ranging from allergens to viral infections. The prevalence and severity of asthma are determined by a complex interplay between genetic and environmental factors. Despite treatment advancements, disparities persist in asthma care, with variations in access to diagnosis, treatment, and patient education across different demographics.

The development of asthma, often presenting in childhood, is associated with other atopic features, such as eczema and hay fever.[1][2][3] Severity varies from intermittent symptoms to life-threatening airway closure. Healthcare professionals establish a definitive diagnosis through patient history, physical examination, pulmonary function testing, and appropriate laboratory testing. Spirometry with a post-bronchodilator response (BDR) is the primary diagnostic test. Treatment focuses on providing continued education, routine symptom assessment, access to fast-acting bronchodilators, and appropriate controller medications tailored to disease severity.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Genetics

Asthma manifests with diverse phenotypes, likely influenced by intricate interactions between genetic and environmental factors.[4][5] Genomewide association studies have linked childhood-onset asthma to markers near the ORMDL sphingolipid biosynthesis regulator 3 (ORMDL3) and gasdermin B (GSDMB) genes on chromosome 17q21, encoding ORM1-like protein 3 and gasdermin-like protein.[6] Other associations include genes such as interleukin-33 (IL33), IL-1 receptor-like 1 (IL1R1) genes, and a novel susceptibility locus at the IF-inducible protein X (PYHIN1) gene, particularly affecting individuals of African descent.[7]

The EVE Consortium also identifies a susceptibility locus for thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), an epithelial cell–derived cytokine implicated in asthma-related inflammation initiation.[8] Asthma patients exhibit higher TSLP expression in their airways compared to healthy controls. Additional genetic loci involved in asthma include major histocompatibility complex class II DQ α1 (HLA-DQA1), HLA-DQB1 antisense RNA 1 (HLA-DQB1), Toll-like receptor 1 (TLR1), IL-6 receptor (IL6R), zona pellucida-binding protein 2 (ZPBP2), and gasdermin A (GSDMA).

Genetics may also be pivotal in asthma treatment. The hydroxy-δ-5-steroid dehydrogenase, 3-beta- and steroid δ-isomerase 1 (HSD3B1) genotype is associated with glucocorticoid resistance among patients. In addition, single-nucleotide polymorphisms in protein kinase cGMP-dependent 1 (PRKG1) and SPATA13 antisense RNA 1 (SPATA13-AS1) are associated with BDR in Black children.[9]

Differing concordance rates among monozygotic twins suggest that exposure to environmental factors has an essential role in the development of asthma. Specific alleles have different effects depending on the environmental exposures. For example, exposure to secondhand smoke associates variations in the N-acetyltransferase 1 (NAT1) gene with the development of asthma in children. A study involving 983 children with single-nucleotide polymorphisms related to ORMDL3 and GSDMB at chromosome locus 17q21 reveals that the same genotype poses genetic risk while also offering environmental protection.[10]

Risk Factors

Risk factors for asthma development encompass exposures throughout a patient's lifespan, including the perinatal period. The most substantial known risk factor is atopy, which is characterized by the genetic tendency to produce specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies in response to common environmental allergens. Nearly one-third of children with atopy will develop asthma later in life.

Prenatal and Perinatal Factors

Prematurity is the most crucial risk factor influencing asthma incidence during this period.[11][12][13][14] Preterm birth, occurring before 36 weeks, is associated with an elevated risk of asthma throughout childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. Researchers posit that impaired lung development in preterm infants, even in those without early respiratory complications, increases the long-term risk of asthma.[15] Exposure to maternal smoking during pregnancy causes diminished pulmonary function in newborns and an increased probability of developing childhood asthma. Moreover, smoking during pregnancy correlates with several adverse pregnancy outcomes, including premature delivery, further elevating the asthma risk.

The incidence of childhood asthma increases with a maternal age of 20 or younger and decreases with a maternal age of 30 or older. Maternal diet during pregnancy holds significance, with researchers suggesting that vitamin D deficiency contributes to early-life wheezing and asthma primarily by impacting the immune function of various cell types, notably dendritic and T regulatory cells. Additionally, vitamin D plays a role in fetal lung development.[16][17] Although some studies present conflicting findings regarding the association between maternal vitamin D levels and childhood asthma, a meta-analysis of 2 large studies indicates that maternal vitamin D intake offers protection against wheezing or asthma in offspring up to the age of 3.[16]

The Copenhagen Prospective Studies on Asthma in Childhood (COPSAC2010) reveals that 17% of children born to mothers with diets high in omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids developed persistent wheeze or asthma during the first 3 years of life compared to nearly 24% in the group with diets high in omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Vitamins E and C and zinc may also have protective effects. Administering vitamin C at a dose of 500 mg/d to pregnant mothers appears to offer protection against the harmful effects of tobacco exposure. Offspring of mothers who receive vitamin C supplementation exhibit a wheezing incidence of 28%, while those without vitamin C supplementation have a higher incidence of 47%.[18][19]

Childhood

Wheezing caused by viral infections, particularly respiratory syncytial virus and human rhinovirus, may predispose infants and young children to develop asthma later in life. In addition, early-life exposure to air pollution, including combustion by-products from gas-fired appliances and indoor fires, obesity, and early puberty, also increases the risk of asthma.

Adulthood

The most significant risk factors for adult-onset asthma include tobacco smoke, occupational exposure, and adults with rhinitis or atopy. Studies also suggest a modest increase in asthma incidence among postmenopausal women taking hormone replacement therapy.

Furthermore, the following factors can contribute to asthma and airway hyperreactivity:

- Exposure to environmental allergens such as house dust mites, animal allergens (especially from cats and dogs), cockroach allergens, and fungi

- Physical activity or exercise

- Conditions such as hyperventilation, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and chronic sinusitis

- Hypersensitivity to aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), as well as sulfite sensitivity

- Use of β-adrenergic receptor blockers, including ophthalmic preparations

- Exposure to irritants such as household sprays and paint fumes

- Contact with various high- and low-molecular-weight compounds found in insects, plants, latex, gums, diisocyanates, anhydrides, wood dust, and solder fluxes, which are associated with occupational asthma

- Emotional factors or stress

Aspirin-Exacerbated Respiratory Disease

Aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD) is a condition characterized by a combination of asthma, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis, and NSAID intolerance. Patients with AERD present with upper and lower respiratory tract symptoms after ingesting aspirin or NSAIDs that inhibit cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1). This condition arises from dysregulated arachidonic acid metabolism and the overproduction of leukotrienes involving the 5-lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase pathways. AERD affects approximately 7% of adults with asthma.

Occupational-Induced Asthma

Two types of occupational asthma exist based on their appearance after a latency period:

- Occupational asthma triggered by workplace sensitizers results from an allergic or immunological process associated with a latency period induced by both low- and high-molecular-weight agents. High-molecular-weight substances, such as flour, contain proteins and polysaccharides of plant or animal origin. Low-molecular-weight substances, like formaldehyde, form a sensitizing neoantigen when combined with a human protein.

- Occupational asthma caused by irritants involves a nonallergic or nonimmunological process induced by gases, fumes, smoke, and aerosols.

Epidemiology

The worldwide incidence of asthma is estimated to affect 260 million individuals.[20] Recent studies examining asthma prevalence across 17 countries reveal varying rates, ranging from 3.4% to 6% for adults and children in India, Taiwan, Kosovo, Nigeria, and Russia, and higher rates of 17% to 33% for Honduras, Costa Rica, Brazil, and New Zealand.[21] Despite data showing the death rate consistently declining for asthma between 2001 and 2015, asthma continues to account for approximately 420,000 deaths per year.[22] Factors such as under-prescription of inhaled glucocorticoids and limited access to emergency medical care or specialist care all play a role in asthma-related deaths.

Asthma prevalence in the United States differs among demographic groups, including age, gender, race, and socioeconomic status. The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that around 25 million Americans are currently affected by asthma. Among individuals younger than 18, boys exhibit a higher prevalence compared to girls, while among adults, women are more commonly affected than men. Additionally, asthma prevalence is notably higher among Black individuals, with a prevalence of 10.1%, compared to White individuals at 8.1%. Hispanic Americans generally have a lower prevalence of 6.4%, except for those from Puerto Rico, where the prevalence rises to 12.8%. Moreover, underrepresented minorities and individuals living below the poverty line experience the highest incidence of asthma, along with heightened rates of asthma-related morbidity and mortality.

Similar to worldwide data, the mortality rate of asthma in the United States has also undergone a consistent decline. The current mortality rate is 9.86 per million compared to 15.09 per million in 2001. However, mortality rates remain consistently higher for Black patients compared to their White counterparts. According to the CDC, from 1999 to 2016, asthma death rates among adults aged 55 to 64 were 16.32 per 1 million persons, 9.95 per 1 million for females, 9.39 per 1 million for individuals who were not Hispanic or Latino, and notably higher at 25.60 per 1 million for Black patients.

Pathophysiology

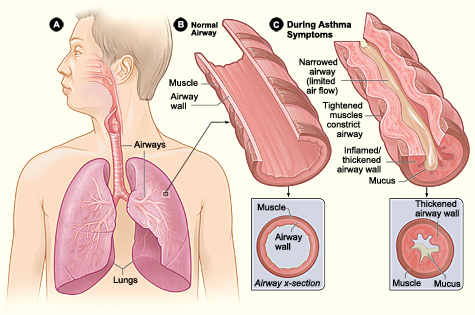

Asthma is a syndrome characterized by diverse underlying mechanisms and involves intricate interactions among inflammatory and resident airway cells. These mechanisms lead to airway inflammation, intermittent airflow obstruction, and bronchial hyperresponsiveness (see Image. Pathophysiology of Asthma).

Airway Inflammation

The activation of mast cells by cytokines and other mediators plays a pivotal role in the development of clinical asthma. Following initial allergen inhalation, affected patients produce specific IgE antibodies due to an overexpression of the T-helper 2 subset (Th2) of lymphocytes relative to the Th1 type. Cytokines produced by Th2 lymphocytes include IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, which promote IgE and eosinophilic responses in atopy. Once produced, these specific IgE antibodies bind to receptors on mast cells and basophils. Upon additional allergen inhalation, allergen-specific IgE antibodies on the mast cell surface undergo cross-linking, leading to rapid degranulation and the release of histamine, prostaglandin D2 (PGD2), and cysteinyl leukotrienes C4 (LTC4), D4 (LTD4), and E4 (LTE4).[23][24] This triggers contraction of the airway smooth muscle within minutes and may stimulate reflex neural pathways. Subsequently, an influx of inflammatory cells, including monocytes, dendritic cells, neutrophils, T lymphocytes, eosinophils, and basophils, may lead to delayed bronchoconstriction several hours later.

Airflow Obstruction

The narrowing of the airway lumen throughout the tracheobronchial tree is caused by the contraction of airway smooth muscle, thickening of the airway wall due to edema, mucus plugging in the airways, and airway remodeling, which collectively contributes to varying levels of airflow obstruction.

Mediators such as histamine and leukotrienes, released from inflammatory cells or through reflex neural pathways, trigger the contraction and relaxation of airway smooth muscle. The precise mechanism leading to airway hyperresponsiveness, characterized by an excessive tightening of the airway's smooth muscles in response to various physical, chemical, or environmental triggers, remains unclear. Some researchers propose alterations in breathing patterns where smooth muscles contract excessively or fail to relax adequately during deep breaths as a potential explanation.

Airway remodeling, which involves thickening of the basement membrane, deposition of collagen, and shedding of epithelial cells, can lead to irreversible changes in the airways. This process accelerates the decline in lung function, particularly in individuals with severe and early-onset asthma.[25] In addition, remodeling contributes to the heightened bronchial sensitivity observed in asthma.

Aspirin-Exacerbated Respiratory Disease

Arachidonic acid metabolism by the enzyme 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO) leads to the generation of leukotrienes, which serve as potent bronchoconstrictors. The metabolism of arachidonic acid by the 2 cyclooxygenase (COX) isoforms—COX-1 and COX-2—generates prostaglandins and thromboxanes. PGD2 is a potent bronchodilator, while PGE2 suppresses the production of leukotrienes. Patients with AERD have dysregulated arachidonic acid metabolism, causing decreased production of PGE2 and loss of control of leukotriene production.[26]

Occupational-Induced Asthma

Patients with occupational-induced asthma can undergo an immunologically mediated response similar to those without occupational-induced asthma. Alternatively, others may present with nonimmunological occupational asthma. The possible underlying mechanisms of the nonimmunological form are denudation of the airway epithelium, direct β-2 adrenergic receptor inhibition, or elaboration of substance P by injured sensory nerves.

History and Physical

History

The 4 cardinal symptoms associated with asthma are wheezing, cough (often worse at night), shortness of breath, and chest tightness. Individuals may experience 1 or more of these symptoms. Asthma symptoms typically occur intermittently, lasting for hours to days, and resolve upon the removal of triggers or the administration of asthma medications. Nighttime exacerbation of symptoms or onset triggered by exercise, cold air, or allergen exposure suggests asthma. In contrast to exertional dyspnea, which manifests shortly after beginning exertion and resolves within 5 minutes of cessation, exercise-induced asthma symptoms typically emerge around 15 minutes into activity and dissipate within 30 to 60 minutes afterward. Patients may also have a history of other forms of atopy, such as eczema and hay fever.

During patient history-taking, healthcare professionals should inquire about particular triggers that exacerbate symptoms. Common household triggers include dust, animals, and infestations of rodents and cockroaches. Some individuals may experience intermittent asthma symptoms related to their work shifts. A strong family history of asthma and allergies, or a personal history of atopic conditions and childhood asthma symptoms, suggests asthma in patients exhibiting suggestive symptoms.

Physical Examination

During physical examination, widespread, high-pitched wheezes are a characteristic finding associated with asthma. However, wheezing is not specific to asthma and is typically absent between acute exacerbations. Findings suggestive of a severe asthma exacerbation include tachypnea, tachycardia, a prolonged expiratory phase, reduced air movement, difficulty speaking in complete sentences or phrases, discomfort when lying supine due to breathlessness, and adopting a "tripod position."[27] The use of the accessory muscles of breathing during inspiration and pulsus paradoxus are additional indicators of a severe asthma attack.

Healthcare professionals may identify extrapulmonary findings that support the diagnosis of asthma, such as pale, boggy nasal mucous membranes, posterior pharyngeal cobblestoning, nasal polyps, and atopic dermatitis. Nasal polyps should prompt further inquiry about anosmia, chronic sinusitis, and aspirin sensitivity to evaluate for AERD. Although AERD is uncommon in children or adolescents, the presence of nasal polyps in a child with lower respiratory disease should prompt an evaluation for cystic fibrosis. Clubbing, characterized by bulbous fusiform enlargement of the distal portion of a digit, is not associated with asthma and should prompt evaluation for alternative diagnoses. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Nail Clubbing," for further information.

Evaluation

Intermittent symptoms consistent with asthma, in addition to wheezing observed during physical examination, strongly indicate asthma. Confirming the diagnosis involves the exclusion of alternative diagnoses and a demonstration of variable airflow limitation, usually seen in spirometry.

Spirometry

Spirometry assesses forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) by measuring a maximal inhalation followed by rapid and forceful exhalation into a spirometer. Asthma typically presents as an obstructive pattern on spirometry, indicated by a reduced FEV1 to FVC ratio.[28] Additionally, a visual examination of the expiratory flow-volume loop can reveal an obstructive pattern. A scooped, concave appearance in the expiratory portion of the flow-volume loop indicates diffuse intrathoracic airflow obstruction characterizes asthma. In rare cases where complete exhalation is impossible, the FEV1/FVC ratio may appear normal, falsely suggesting a restrictive pattern if not assessed along with flow-time curves.

Patients showing airflow limitations on spirometry receive 2 to 4 puffs of a short-acting bronchodilator like albuterol, followed by repeat spirometry in 10 to 15 minutes. According to the European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society guidelines, a positive BDR is determined by a change in FEV1 or FVC compared to their predicted value. Clinicians calculate the patient's BDR using the formula:

BDR=([Post-bronchodilator value – Pre-bronchodilator value] × 100) / Predicted value of either FEV1 or FVC

Increases exceeding 10% are considered significant.[28]

According to the Global Initiative for Asthma, a significant BDR is indicated by an increase in the FEV1 of 12% or 200 mL or more. In addition, the slow vital capacity, or the maximal amount of air exhaled in a relaxed expiration from full inspiration to residual volume over 15 seconds, may also be helpful when the FVC is reduced and airway obstruction is present. During slow exhalation, airway narrowing is less pronounced, and the patient can produce a larger vital capacity. In cases of restrictive disease, both slow and fast exhalations result in reduced vital capacity.

Spirometry results may be normal in asymptomatic individuals or those with cough-variant asthma. Bronchodilator responsiveness is evident in asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cystic fibrosis, non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis, and bronchiolitis. However, patients with asthma may yield false negative results if they are on chronic controller medications, exhibit underlying airway remodeling, have minimal symptoms during testing, or have recently used bronchodilators before the test. Ideally, clinicians should conduct baseline spirometry before commencing treatment.[29][30]

Bronchoprovocation Testing

During bronchoprovocation testing, clinicians induce bronchoconstriction using inhaled methacholine or mannitol, exercise, or eucapnic hyperventilation of dry air. This testing method can be beneficial for patients presenting with atypical symptoms or an isolated cough. Patients receive incremental doses of the provocative agent followed by spirometry to generate a dose-response curve. A fall in FEV1 of 20% or more from baseline with the standard dose of methacholine or a decline of 15% or more with the standard dose of hypertonic saline, mannitol, or hyperventilation indicates a positive test.[31] Clinicians may also conduct additional provocative testing using exercise, aspirin, and exposure to environmental triggers encountered in the workplace.

Peak Flow Meter

Although consistent reductions of 20% during symptomatic periods, followed by a gradual return to baseline as symptoms resolve, indicate asthma, clinicians typically use peak flow measurement to monitor patients with known asthma rather than for initial diagnosis. To measure peak flow, the patient takes a maximal breath and seals the peak flow meter between their lips before blowing forcefully for 1 to 2 seconds. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Peak Flow Measurement," for additional information regarding peak flow measurement and its clinical significance in the evaluation and management of asthma.

Patients repeat this process 3 times, recording the highest reading as the current peak flow measurement. Patients can compare their recorded values to established graphs based on age and height for adults and height for adolescents to determine their predicted value. Notably, reduced peak flow values are not specific to asthma. Patients with either an obstructive or restrictive pattern on spirometry can have decreased peak flow values. Additionally, the accuracy of results is highly contingent on patient effort.

Exhaled Nitric Oxide

Eosinophilic airway inflammation causes an upregulation of nitric oxide synthase in the respiratory mucosa, leading to elevated nitric oxide levels in exhaled breath. In certain asthma patients, the fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FENO) surpasses levels observed in individuals without asthma. A FENO of measurement exceeding 40 to 50 ppb can aid in confirming an asthma diagnosis.

Pulse Oximetry

Pulse oximetry can help assess the severity of an asthma attack or monitor for deterioration. Notably, pulse oximetry measurements may exhibit a lag, and the physiological reserve of many patients implies that a declining oxygen level on pulse oximetry is a late stage, indicating an increasingly unwell or peri-arrest patient.

Laboratory

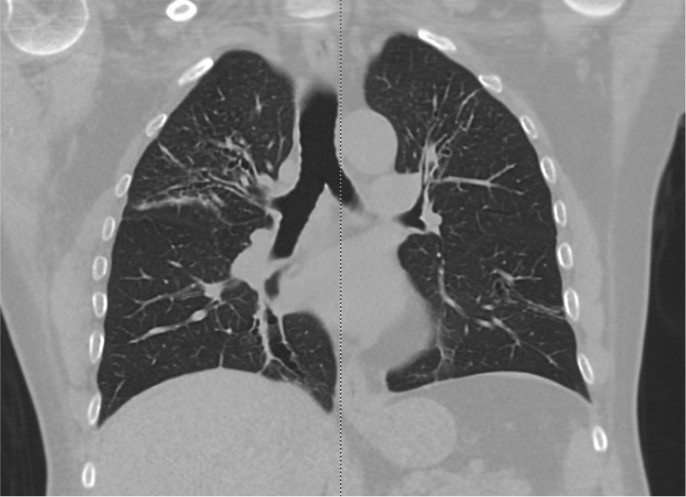

No specific laboratory tests are necessary for diagnosing asthma. However, patients who present with a severe asthma exacerbation should undergo a complete blood count to evaluate eosinophil levels and check for anemia, which may be the underlying cause of the patient's dyspnea. A significantly elevated eosinophil count should prompt further investigation for conditions, including parasitic infections such as Strongyloides, drug reactions, and syndromes characterized by pulmonary infiltrates with eosinophilia. These syndromes include allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and hypereosinophilic syndrome (see Image. Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis on CT Scan).

Non-smoking patients who present with irreversible airflow obstruction should undergo serum α1-antitrypsin level testing to rule out emphysema caused by homozygous α1-antitrypsin deficiency. Allergy testing may prove beneficial for patients experiencing symptoms upon exposure to specific allergens. Clinicians should obtain total serum IgE levels in patients with moderate-to-severe persistent asthma, particularly when considering treatment with anti-IgE monoclonal antibodies or when there is suspicion of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Please refer to the Treatment/Management section for further details on anti-IgE monoclonal antibodies.

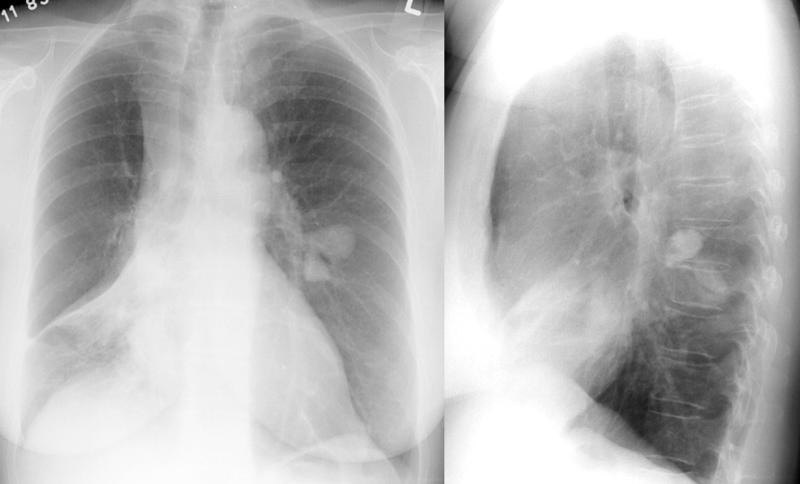

Imaging

Chest radiographs in asthma patients are often normal; however, during acute exacerbations, abnormal findings such as hyperinflation, pneumomediastinum, and bronchial thickening may be observed (see Image. A Chest Radiograph Depicting Asthma). A chest radiograph is recommended for patients aged 40 or older with new-onset, moderate-to-severe asthma to rule out conditions that can mimic asthma, such as a mediastinal mass with tracheal compression or heart failure.

Additional indications for chest radiography include patients experiencing symptoms that are difficult to control, fever, chronic purulent sputum production, persistently localized wheezing, hemoptysis, weight loss, clubbing, inspiratory crackles, significant hypoxemia, and moderate or severe airflow obstruction that does not reverse with bronchodilators. High-resolution computed tomography is necessary to clarify any abnormalities noted on chest radiographs or for patients with other suspected conditions that may not be well visualized on routine radiographs.

Evaluation During an Acute Exacerbation

Each patient should undergo a rapid assessment of their vital signs, including oxygen saturation. Measuring the peak flow can indicate the severity of the exacerbation and monitor the response to therapy. Predicted peak flow measurements vary based on age and height; however, a peak flow below 200 L/min indicates severe obstruction except in patients aged 65 or older or with very short stature. A peak flow measurement below 50% predicted or the patient's personal best is considered severe, while between 50% and 70% is considered moderate. Chest radiographs are not uniformly necessary unless the diagnosis of acute asthma exacerbation is uncertain, the patient requires hospitalization, or evidence of a comorbid condition is present.

Identification of Patients at Risk of Fatal or Near-Fatal Asthma

Most asthma-related deaths are preventable if risk factors are identified and addressed early. Major risk factors that place patients at high risk for future fatal asthma exacerbations include:

- A recent history of poorly controlled asthma

- A prior history of near-fatal asthma

- A history of endotracheal intubation for asthma

- A history of intensive care unit admission for asthma

Minor risk factors include exposure to aeroallergens and tobacco smoke, illicit drug use, older patients, aspirin sensitivity, long duration of asthma, and frequent hospitalizations for asthma-related issues.

Treatment / Management

Patient Education

Multiple sources of patient education are available. According to the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program's Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma, personalized education from the patient's primary clinician is especially impactful. Studies reveal that such education reduces the number of asthma exacerbations and hospitalizations. Healthcare professionals should provide culturally specific asthma education that includes understanding asthma and its symptoms, identifying the patient's specific triggers, and strategies for their avoidance. Each patient should understand how to properly use an inhaler and be familiar with medications that serve as rescue options, those used for symptom control, and those that may fulfill both roles. Clinicians should inquire about any obstacles hindering medication adherence and work collaboratively with patients to overcome concerns or barriers, thus enhancing overall adherence.

Although the data on effectiveness are limited, a general consensus among experts exists that individuals with asthma should possess a personalized "action plan" to follow at home (please refer to the link to an action plan download in the Deterrence and Patient Education section). This action plan provides a structured maintenance medication regimen and delineates steps to take when symptoms exacerbate. Clinicians develop an action plan based on symptoms or peak flow readings and divide it into 3 zones—green, yellow, and red.

Patients in the green zone are asymptomatic, with peak flows at 80% or higher than their personal best. They feel well and continue with their long-term control medication. Peak flow readings falling within the yellow zone range between 50% and 79% of the patient's personal best, accompanied by symptoms such as coughing, wheezing, and shortness of breath, which begin to interfere with activity levels. In the red zone, patients experience peak flow readings below 50% of their best, severe shortness of breath, and an inability to perform everyday activities.

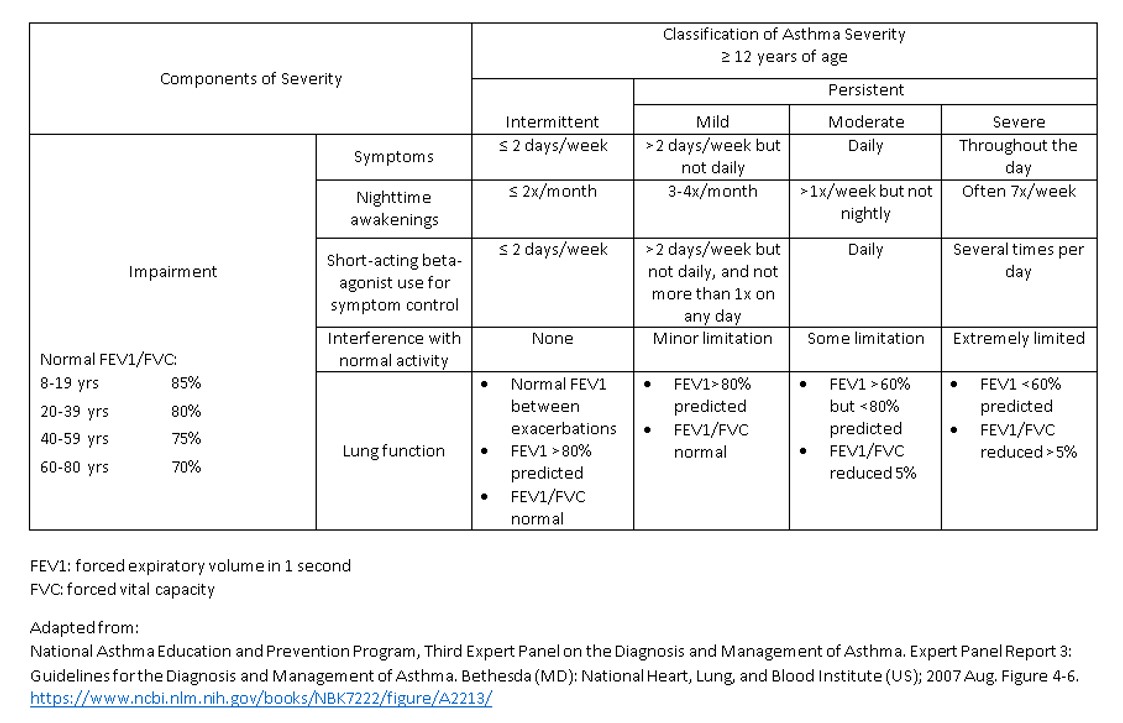

Asthma Severity

Guidelines established by the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) and the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) determine therapy based on the frequency and severity of asthma symptoms, the degree of respiratory impairment, and the risk of future exacerbations. Risk factors contributing to future exacerbations include frequent asthma symptoms, a history of intensive care unit admission for asthma, obesity, poor medication adherence, chronic rhinosinusitis, and a low FEV1. The severity categories and treatment guidelines vary based on age. This activity will address asthma severity and management in adolescents and adults aged 12 or older. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Pediatric Asthma," for additional information regarding the treatment of asthma in infants and children.

Every patient should have access to a bronchodilator with a rapid onset of action. Traditionally, this has been a short-acting β-agonist (SABA) such as albuterol. However, GINA recommends a low-dose glucocorticoid/formoterol inhaler, such as 80 to 160 mcg budesonide/4.5 mcg formoterol inhaled by mouth 1 or 2 times daily, for asthma symptoms. Notably, this is an off-label indication for this preparation.

Treatment progresses in a stepwise manner, with the highest severity category in which the patient experiences any symptoms, designating the treatment category from which the patient receives treatment (see Image. Asthma Severity Classification by National Asthma Education and Prevention Program). Tables 1 and 2 below include the NAEPP and GINA asthma severity classifications and treatment initiation guidelines based on the patient's symptoms and lung function.

Table 1. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program: Expert Panel Working Group Initial Asthma Therapy in Adolescents and Adults

| Steps | Asthma Symptoms/Lung Functions | Therapies |

| Step 1 |

Must have all of the following: Daytime symptoms ≤2 days per week Nocturnal awakenings ≤2 per month Normal FEV1 Exacerbations ≤1 per year |

SABA, as needed. Patients with exercise-induced asthma should use 1 to 2 puffs of a SABA inhaler for 5 to 20 minutes before engaging in a designated physical activity. |

| Step 2 | If any of the following:

Daytime symptoms >2 but <7 days per week Nocturnal awakenings up to 3 to 4 nights per month Minor interference with activities Exacerbations ≥2 per year |

Preferred: Low-dose ICS daily and SABA as needed. Or, Low-dose ICS-SABA or ICS plus SABA, concomitantly administered as needed. Alternative option(s): Daily LTRA and SABA as needed. |

| Step 3 | If any of the following:

Daily asthma symptoms Nocturnal awakenings >1 per week Need daily relief inhaler Some activity limitation FEV1 60% to 80% predicted Exacerbations ≥2 per year |

Preferred: Low-dose ICS-formoterol as maintenance and reliever therapy. Alternative option(s): Medium-dose ICS daily and SABA as needed. Or, Low-dose ICS-LABA combination daily, low-dose ICS plus LAMA daily, or low-dose ICS plus anti-leukotriene daily and SABA as needed. |

| Step 4 | If any of the following:

Symptoms all-day Nightly awakenings due to asthma symptoms Need for SABA several times per day Extreme limitation in activity FEV1 <60% predicted Exacerbations ≥2 per year An acute exacerbation |

Preferred: Medium-dose ICS-formoterol as maintenance and reliever therapy. Alternative option(s): Medium-dose ICS-LABA daily or medium-dose ICS plus LAMA daily. Or, Medium-dose ICS daily plus anti-leukotrieneand SABA as needed. |

Abbreviations: FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting β-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; LTRA, leukotriene receptor antagonist; SABA, short-acting β-agonist.

Table 2. Global Initiative for Asthma Initial Asthma Therapy in Adolescents and Adults

| Steps | Asthma Symptoms/Lung Functions | Therapies |

| Step 1 |

Asthma symptoms <2 times per week No risk factors for exacerbations |

Preferred: Low-dose ICS-formoterol as needed. Or, Low-dose ICS whenever SABA is used or as-needed low-dose ICS-SABA. Patients with exercise-induced asthma should use 1 to 2 puffs for 5 to 20 minutes before engaging in a designated activity. |

| Step 2 |

Asthma symptoms or need for reliever inhaler ≥2 times per week No daily symptoms |

Preferred: Low-dose ICS-formoterol as needed. Or, Low-dose ICS daily and SABA as needed Other option(s): Low-dose ICS-SABA or ICS plus SABA, concomitantly administered as needed. Or, Less preferred: LTRA daily and SABA as needed. |

| Step 3 |

Asthma symptoms most days Nocturnal awakening due to asthma ≥1 time per month Multiple risk factors for exacerbations |

Preferred: Low-dose ICS-formoterol as maintenance and reliever therapy. Or, Low-dose ICS-LABA combination daily and SABA as needed. Other option(s): Medium-dose ICS daily and SABA or ICS-SABA as needed. Or, Low-dose ICS plus LTRA daily and SABA or ICS-SABA as needed. |

| Step 4 | Severely uncontrolled asthma with ≥3 of the following:

Daytime asthma symptoms >2 times per week Nocturnal awakening due to asthma Reliever needed for symptoms >2 times per week Activity limitation due to asthma |

Preferred: Medium-dose ICS-formoterol as maintenance and reliever therapy. Or, Medium dose ICS-LABA daily and SABA or ICS-SABA as needed. Other option(s): Possible add-on LAMA or switch to ICS-LAMA-LABA. Possible add-on LTRA. |

| Step 5 |

A LAMA can be added. The patient should be referred for phenotypic assessment and possible biological therapy. High-dose ICS-formoterol should be considered. Possibly LTRA. Low-dose OCS as a last resort. |

Abbreviations: ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting β-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; LTRA, leukotriene receptor antagonist; OCS, oral corticosteroid; SABA, short-acting β-agonist.

Routine follow-up every 1 to 6 months is necessary to ensure adequate symptom management. Upon reevaluation, patients facing inadequate asthma symptom management, exacerbations necessitating systemic glucocorticoids, or those at high risk of exacerbation on their current therapy level should escalate to the next level of therapy. Therapy adjustments proceed incrementally until symptoms are adequately managed. After maintaining control for 3 to 6 months, clinicians may consider gradual therapy reduction following the stepwise protocols outlined by GINA or NAEPP guidelines.

Severe Asthma

Adults and adolescents with severe asthma that remains uncontrolled despite Step 4 recommended therapy should receive a LAMA, such as tiotropium, alongside their inhaled glucocorticoid and LABA regimen. Clinicians should direct these patients for phenotypic assessment and consideration for biological therapy options. Anti-IgE monoclonal antibody therapy with omalizumab may be helpful for those still experiencing inadequate control and possessing documented sensitivity to a perennial allergy with IgE levels ranging between 30 and 700 IU/mL.

Patients with severe eosinophilic asthma who are not adequately controlled can utilize mepolizumab and reslizumab, monoclonal antibodies against IL-5, benralizumab, a monoclonal antibody against the IL-5 receptor α-subunit, and dupilumab a monoclonal antibody against the IL-4 receptor α-subunit. Tezepelumab is a human monoclonal IgG2-λ antibody that binds to TSLP, preventing its interaction with the TSLP receptor complex.[32]

Acute Exacerbation

Patients experiencing an acute asthma exacerbation may manage symptoms at home or need urgent medical care depending on their symptom severity and risk factors for fatal asthma. These risk factors include prior life-threatening exacerbations, exacerbations despite glucocorticoid use, more than 1 asthma-related hospitalization or 3 emergency room visits in the past year, and comorbidities such as cardiovascular or chronic lung disease. Immediate medical attention is warranted for patients showing significant breathlessness, inability to speak beyond short phrases, reliance on accessory muscles, or peak flow measurements at 50% or less of their baseline measurement.

All patients require a fast-acting β-agonist. Potential options include the LABA formoterol combined with ICS, the SABA albuterol combined with budesonide, or albuterol alone. Combination with ICS is the preferred choice. Albuterol dosing is 2 to 4 puffs from a metered dose inhaler (MDI) at home and 4 to 8 puffs in the office with a valved holding chamber or spacer every 20 minutes for 1 hour as needed. Albuterol may also be nebulized. ICS-formoterol dosing is 1 to 2 puffs every 20 minutes for 1 hour as required, with a maximum of 8 puffs per day.

Patients whose symptoms improve after administering a bronchodilator and whose peak flow returns to 80% of their baseline or better can continue to manage their symptoms at home. Oral glucocorticoids equivalent to 40 to 60 mg prednisone daily for 5 to 7 days are warranted for the following patients:

- Those experiencing recurrent symptoms over the following 1 to 2 days.

- Those whose peak flow remains less than 80% of their normal baseline (high-dose ICSs are an alternative).

- If they do not improve after 1 to 3 doses of a fast-acting bronchodilator.

- If they have recently completed a course in OCS.

- Those who are on a maximal dose of controller medications.

Patients with a peak flow value of 50% or lower despite administering a bronchodilator or continuing to worsen should seek immediate medical care while continuing to administer their fast-acting bronchodilator.

Office management is similar to home management, with the addition that according to GINA guidelines, all patients with oxygen saturation below 90% should receive oxygen to maintain saturation above 92% or 95% for pregnant individuals. Albuterol treatment can be administered via an MDI or nebulizer, with a dosage of 4 to 8 puffs or 2.5 to 5 mg every 20 minutes for 1 hour, respectively. Research comparing the efficacy of an MDI combined with a valved-holding chamber to nebulizer delivery, both administering the same β-agonist but with significantly lower doses via MDI, demonstrates similar enhancements in lung function and risk reduction for hospitalization.[33][34][35] (A1)

If oral glucocorticoids are unavailable, intramuscular steroids such as triamcinolone suspension (40 mg/mL) 60 to 100 mg can be an alternative. However, it is noteworthy that intramuscular glucocorticoids have a delayed onset of action of 12 to 36 hours. Patients meeting certain criteria such as a respiratory rate of 30 breaths per minute, a heart rate of more than 120 bpm, a continued peak flow of less than 50% predicted, oxygen saturation of less than 90%, or the inability to speak in full sentences should be transferred to the emergency department.

Patients who can be sent home from the office should have their controller medications advanced in 1 step. In addition, it is essential to review the correct use of their inhaler, discuss trigger avoidance strategies, ensure they have an asthma action plan, and emphasize the importance of adhering to their controller medication.

Emergency Department Care

Within the first hour, patients should receive 3 treatments of an inhaled SABA, such as albuterol, via a nebulizer or MDI, followed by repeat dosing every 1 to 4 hours. In addition to a SABA, patients with severe asthma exacerbations should also receive inhaled ipratropium, a short-acting muscarinic antagonist (SAMA), at a dosage of 500 µg by nebulization or 4 to 8 puffs by MDI, every 20 minutes for 3 doses, and then hourly as needed for up to 3 hours. Current guidelines recommend discontinuing SAMA therapy once the patient requires hospital admission, except in specific cases such as refractory asthma requiring treatment in the intensive care unit, concurrent treatment with monoamine oxidase inhibitors due to potential increased toxicity from sympathomimetic therapy due to impaired drug metabolism, presence of COPD with an asthmatic component, or asthma triggered by β-blocker therapy.

As with outpatient management, patients also receive glucocorticoids equivalent to 40 to 60 mg of prednisone daily for 5 to 7 days. A systematic review reveals no difference between a higher dose and a longer course when compared to a lower dose with a shorter course of prednisone or prednisolone.[36] Oral and intravenous glucocorticoids have equivalent effects when administered in comparable doses. Intravenous steroids are necessary for patients with impending or actual respiratory arrest or who are intolerant of oral glucocorticoids. Some clinicians administer higher doses of glucocorticoids for severe asthma exacerbations based on their expert opinion and concern that a lower dose might be insufficient in a critically ill patient. (A1)

Magnesium sulfate

Per GINA guidelines, magnesium is not recommended for routine use in asthma exacerbations. However, a 1-time dose of 2 g given intravenously over 20 minutes reduces hospitalization rates in adults with an FEV1 less than 25% to 30% predicted on presentation and in those who fail to respond to initial treatment and continue to have hypoxemia. Nebulized MgSO4 is not beneficial in the management of an acute asthma exacerbation.

A Cochrane Database review in 2014 concluded that a single infusion of intravenous MgSO4 for patients not responding to conventional therapy results in improved lung functions and fewer hospital admissions.[37] However, in a recent systematic review, the comparison of the same studies, eliminating those involving children and those containing only abstracts, revealed conflicting results. The review examined the effects of intravenous and nebulized MgSO4. Although 3 out of 9 studies addressing treatment with intravenous MgSO4 found a significant effect on lung function compared to placebo, these results are not statistically significant.[38] Only 2 of the 8 studies investigating hospital admission rates reveal a significant effect of MgSO4.[38] Conversely, 6 of the 9 studies investigating treatment with nebulized MgSO4 compared to placebo reveal a favorable effect on the FEV1 and peak expiratory flow rate.[38] These results somewhat contradict the Cochrane Database review conducted in 2014, which evaluated the same studies.[37] (A1)

An additional study reveals a small benefit of adding inhaled magnesium to inhaled albuterol plus ipratropium in reducing hospital admissions but no significant improvement in peak expiratory flow when added to inhaled albuterol plus ipratropium or inhaled albuterol alone.[39] (A1)

Intubation or Noninvasive Ventilation

Indications for intubation and mechanical ventilation or noninvasive ventilation include the following:

- Slowing of the respiratory rate

- Depressed mental status

- Inability to maintain respiratory effort

- Inability to cooperate with the administration of inhaled medications

- Worsening hypercapnia and associated respiratory acidosis

- Inability to maintain oxygen saturation above 92% despite face mask supplemental oxygen

A 1- to 2-hour trial of bilevel noninvasive positive pressure ventilation is appropriate for patients with an acute asthma exacerbation, but clinicians should maintain a low threshold for intubation.[40][41] (A1)

Additional Therapies

Occasionally, nonstandard therapies, such as ketamine, halothane, helium-oxygen mixtures, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and parenteral terbutaline, can be helpful for certain patients. However, these therapies are not routinely utilized due to limited evidence of efficacy. The indication for parenteral epinephrine is asthma associated with anaphylaxis and angioedema.

All patients who are smokers should be educated on the benefits of smoking cessation and provided with appropriate support and resources. Empiric antibiotics are not recommended since most infections triggering asthma exacerbations are viral. According to both GINA and NAEPP guidelines, intravenous methylxanthines such as theophylline are deemed ineffective and are no longer part of the standard of care.[42](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses for asthma include the following conditions:

- Bronchiectasis

- Bronchiolitis

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Chronic sinusitis

- Cystic fibrosis

- α1-antitrypsin deficiency

- Aspergillosis

- Exercise-induced anaphylaxis

- Foreign body aspiration

- Heart failure

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- Tracheomalacia

- Pulmonary embolism

- Pulmonary eosinophilia

- Sarcoidosis

- Upper respiratory tract infection

- Vocal cord dysfunction

- Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Bronchogenic carcinoma

- Post-viral tussive syndrome

- Eosinophilic bronchitis

- Cough induced by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

- Bordetella pertussis infection

- Interstitial lung disease

- Obesity

- Recurrent oropharyngeal aspiration

Prognosis

The development and prognosis of asthma involve a complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors. Social determinants of health, such as poor housing quality and indoor and outdoor pollution, profoundly impact asthma prognosis. In the United States, asthma is a chronic illness characterized by a significant racial and ethnic disparity in both prevalence and prognosis. Underrepresented racial and ethnic minorities, as well as individuals living below the poverty line, experience higher morbidity rates, increased emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and mortality due to asthma.[43][44] Additionally, lack of access to healthcare—whether due to difficulties in accessing clinicians or lack of insurance—further exacerbates prognosis-related challenges.

The international asthma mortality rate reaches as high as 0.86 deaths per 100,000 persons in certain countries. The overall prognosis is predominantly linked to lung function, with mortality rates 8 times higher among individuals in the bottom 25% of lung function. Several factors contribute to a poorer prognosis, including inadequate asthma management, age 40 or older, a history of more than 20 pack-years of cigarette smoking, blood eosinophilia, and FEV1 of 40% to 69% of predicted values

Complications

The complications related to asthma include disease-related complications and adverse effects of glucocorticoids, LTRA, and endotracheal intubation. The following list contains complications associated with asthma:

- Decline in lung function

- Osteoporosis

- Fracture

- Infections

- Adrenal suppression

- Hypertension

- Diabetes

- Cataract

- Peptic ulcer

- Sleep disorders

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- Mood disorders

- Cardiac arrest

- Glaucoma

- Respiratory failure or arrest

- Pneumothorax

- Aspiration [45]

Consultations

Healthcare professionals should seek consultation with an asthma specialist in pulmonology or allergy when the diagnosis of asthma is uncertain, the patient's symptoms remain poorly controlled, medication adverse effects become intolerable, or the patient experiences frequent exacerbations. Accessing appropriate specialist care aids in excluding alternate diagnoses, determining the need for additional diagnostic testing, and effectively escalating medical therapy.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education plays a pivotal role in the effective management of asthma by clinicians. To deter exacerbations and improve patient outcomes, clinicians should emphasize the importance of adherence to medication regimens, avoidance of triggers, and regular monitoring of symptoms. Educating patients about asthma triggers, such as allergens, air pollution, and tobacco smoke, can empower them to make informed lifestyle choices. Furthermore, clinicians should highlight the significance of having an asthma action plan, which outlines steps to take during worsening symptoms or exacerbations. See the National Heart and Lung Institute's website, "Asthma Action Plan," for a printable version of an action plan.

Patient education should also prioritize the recognition of early warning signs of an asthma attack and prompt seeking of medical attention when necessary. Routine follow-up visits for patients with active asthma are recommended, occurring every one to six months, contingent on the severity of asthma and adequacy of control. During these follow-up visits, clinicians should assess asthma control, lung function, exacerbations, inhaler technique, adherence, adverse effects of medication, quality of life, and patient satisfaction with care. By instilling a comprehensive understanding of asthma management strategies and fostering proactive patient involvement, clinicians can significantly reduce the burden of asthma and enhance patient well-being.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Asthma is characterized by complex pathophysiology involving airway inflammation, intermittent airflow obstruction, and bronchial hyperresponsiveness. The condition presents various signs and symptoms, such as wheezing, coughing, shortness of breath, and chest tightness. Wheezing may not always be present, particularly in cases primarily affecting small airways, and its absence does not exclude asthma. Additionally, a cough might be the sole symptom, especially one that occurs or worsens at night. Diagnostic evaluation involves spirometry, assessing lung function parameters such as FEV1 and FVC, measuring peak flow, and possibly conducting bronchoprovocation testing in some individuals.

Treatment strategies include trigger avoidance, ensuring access to rescue medications, and personalized pharmacological interventions, with inhaled corticosteroids being the preferred controller medication. Patient education, regular assessment of symptom control, and adherence to treatment plans are crucial components in effectively managing asthma. Adequate patient readiness and preparation, including the development of an asthma action plan, help minimize illness severity and optimize patient outcomes by promoting self-management and reducing healthcare utilization.

Enhancing patient-centered care, outcomes, patient safety, and team performance in asthma management demands a strategic approach. Each healthcare team member should possess the necessary clinical expertise to diagnose and treat asthma effectively, which involves interpreting spirometry findings and customizing treatment plans according to individual patient needs. Adhering to evidence-based guidelines and protocols will ensure uniform practices across healthcare settings.

Effective interprofessional communication enables the exchange of information, collaborative decision-making, and seamless care transitions. Each healthcare team member, including physicians, advanced care practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, respiratory therapists, and social workers, contributes unique skills to asthma care, further enriching interdisciplinary collaboration. By fostering a culture of collaboration, communication, and coordination, healthcare professionals can deliver comprehensive, patient-centered asthma care, decreasing morbidity and mortality and enhancing team performance.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Lee J, McDonald C. Review: Immunotherapy improves some symptoms and reduces long-term medication use in mild to moderate asthma. Annals of internal medicine. 2018 Aug 21:169(4):JC17. doi: 10.7326/ACPJC-2018-169-4-017. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30128507]

Tesfaye ZT, Gebreselase NT, Horsa BA. Appropriateness of chronic asthma management and medication adherence in patients visiting ambulatory clinic of Gondar University Hospital: a cross-sectional study. The World Allergy Organization journal. 2018:11(1):18. doi: 10.1186/s40413-018-0196-1. Epub 2018 Aug 10 [PubMed PMID: 30128064]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSalo PM, Cohn RD, Zeldin DC. Bedroom Allergen Exposure Beyond House Dust Mites. Current allergy and asthma reports. 2018 Aug 20:18(10):52. doi: 10.1007/s11882-018-0805-7. Epub 2018 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 30128784]

Piloni D, Tirelli C, Domenica RD, Conio V, Grosso A, Ronzoni V, Antonacci F, Totaro P, Corsico AG. Asthma-like symptoms: is it always a pulmonary issue? Multidisciplinary respiratory medicine. 2018:13():21. doi: 10.1186/s40248-018-0136-5. Epub 2018 Aug 3 [PubMed PMID: 30123502]

Aggarwal B, Mulgirigama A, Berend N. Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction: prevalence, pathophysiology, patient impact, diagnosis and management. NPJ primary care respiratory medicine. 2018 Aug 14:28(1):31. doi: 10.1038/s41533-018-0098-2. Epub 2018 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 30108224]

Gui H, Levin AM, Hu D, Sleiman P, Xiao S, Mak ACY, Yang M, Barczak AJ, Huntsman S, Eng C, Hochstadt S, Zhang E, Whitehouse K, Simons S, Cabral W, Takriti S, Abecasis G, Blackwell TW, Kang HM, Nickerson DA, Germer S, Lanfear DE, Gilliland F, Gauderman WJ, Kumar R, Erle DJ, Martinez FD, Hakonarson H, Burchard EG, Williams LK. Mapping the 17q12-21.1 Locus for Variants Associated with Early-Onset Asthma in African Americans. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2021 Feb 15:203(4):424-436. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202006-2623OC. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32966749]

Torgerson DG, Ampleford EJ, Chiu GY, Gauderman WJ, Gignoux CR, Graves PE, Himes BE, Levin AM, Mathias RA, Hancock DB, Baurley JW, Eng C, Stern DA, Celedón JC, Rafaels N, Capurso D, Conti DV, Roth LA, Soto-Quiros M, Togias A, Li X, Myers RA, Romieu I, Van Den Berg DJ, Hu D, Hansel NN, Hernandez RD, Israel E, Salam MT, Galanter J, Avila PC, Avila L, Rodriquez-Santana JR, Chapela R, Rodriguez-Cintron W, Diette GB, Adkinson NF, Abel RA, Ross KD, Shi M, Faruque MU, Dunston GM, Watson HR, Mantese VJ, Ezurum SC, Liang L, Ruczinski I, Ford JG, Huntsman S, Chung KF, Vora H, Li X, Calhoun WJ, Castro M, Sienra-Monge JJ, del Rio-Navarro B, Deichmann KA, Heinzmann A, Wenzel SE, Busse WW, Gern JE, Lemanske RF Jr, Beaty TH, Bleecker ER, Raby BA, Meyers DA, London SJ, Mexico City Childhood Asthma Study (MCAAS), Gilliland FD, Children's Health Study (CHS) and HARBORS study, Burchard EG, Genetics of Asthma in Latino Americans (GALA) Study, Study of Genes-Environment and Admixture in Latino Americans (GALA2) and Study of African Americans, Asthma, Genes & Environments (SAGE), Martinez FD, Childhood Asthma Research and Education (CARE) Network, Weiss ST, Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP), Williams LK, Study of Asthma Phenotypes and Pharmacogenomic Interactions by Race-Ethnicity (SAPPHIRE), Barnes KC, Genetic Research on Asthma in African Diaspora (GRAAD) Study, Ober C, Nicolae DL. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of asthma in ethnically diverse North American populations. Nature genetics. 2011 Jul 31:43(9):887-92. doi: 10.1038/ng.888. Epub 2011 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 21804549]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceParnes JR, Molfino NA, Colice G, Martin U, Corren J, Menzies-Gow A. Targeting TSLP in Asthma. Journal of asthma and allergy. 2022:15():749-765. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S275039. Epub 2022 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 35685846]

Fishe JN, Labilloy G, Higley R, Casey D, Ginn A, Baskovich B, Blake KV. Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) in PRKG1 & SPATA13-AS1 are associated with bronchodilator response: a pilot study during acute asthma exacerbations in African American children. Pharmacogenetics and genomics. 2021 Sep 1:31(7):146-154. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0000000000000434. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33851947]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLoss GJ, Depner M, Hose AJ, Genuneit J, Karvonen AM, Hyvärinen A, Roduit C, Kabesch M, Lauener R, Pfefferle PI, Pekkanen J, Dalphin JC, Riedler J, Braun-Fahrländer C, von Mutius E, Ege MJ, PASTURE (Protection against Allergy Study in Rural Environments) Study Group. The Early Development of Wheeze. Environmental Determinants and Genetic Susceptibility at 17q21. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2016 Apr 15:193(8):889-97. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201507-1493OC. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26575599]

Jaakkola JJ, Ahmed P, Ieromnimon A, Goepfert P, Laiou E, Quansah R, Jaakkola MS. Preterm delivery and asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2006 Oct:118(4):823-30 [PubMed PMID: 17030233]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBeen JV, Lugtenberg MJ, Smets E, van Schayck CP, Kramer BW, Mommers M, Sheikh A. Preterm birth and childhood wheezing disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS medicine. 2014 Jan:11(1):e1001596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001596. Epub 2014 Jan 28 [PubMed PMID: 24492409]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLeps C, Carson C, Quigley MA. Gestational age at birth and wheezing trajectories at 3-11 years. Archives of disease in childhood. 2018 Dec:103(12):1138-1144. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-314541. Epub 2018 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 29860226]

Crump C, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Preterm or early term birth and long-term risk of asthma into midadulthood: a national cohort and cosibling study. Thorax. 2023 Jul:78(7):653-660. doi: 10.1136/thorax-2022-218931. Epub 2022 Jul 30 [PubMed PMID: 35907641]

Castro-Rodriguez JA, Forno E, Rodriguez-Martinez CE, Celedón JC. Risk and Protective Factors for Childhood Asthma: What Is the Evidence? The journal of allergy and clinical immunology. In practice. 2016 Nov-Dec:4(6):1111-1122. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.05.003. Epub 2016 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 27286779]

Wolsk HM, Chawes BL, Litonjua AA, Hollis BW, Waage J, Stokholm J, Bønnelykke K, Bisgaard H, Weiss ST. Prenatal vitamin D supplementation reduces risk of asthma/recurrent wheeze in early childhood: A combined analysis of two randomized controlled trials. PloS one. 2017:12(10):e0186657. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186657. Epub 2017 Oct 27 [PubMed PMID: 29077711]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLitonjua AA, Weiss ST. Is vitamin D deficiency to blame for the asthma epidemic? The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2007 Nov:120(5):1031-5 [PubMed PMID: 17919705]

McEvoy CT, Schilling D, Clay N, Jackson K, Go MD, Spitale P, Bunten C, Leiva M, Gonzales D, Hollister-Smith J, Durand M, Frei B, Buist AS, Peters D, Morris CD, Spindel ER. Vitamin C supplementation for pregnant smoking women and pulmonary function in their newborn infants: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014 May:311(20):2074-82. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5217. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24838476]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMcEvoy CT, Shorey-Kendrick LE, Milner K, Schilling D, Tiller C, Vuylsteke B, Scherman A, Jackson K, Haas DM, Harris J, Schuff R, Park BS, Vu A, Kraemer DF, Mitchell J, Metz J, Gonzales D, Bunten C, Spindel ER, Tepper RS, Morris CD. Oral Vitamin C (500 mg/d) to Pregnant Smokers Improves Infant Airway Function at 3 Months (VCSIP). A Randomized Trial. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2019 May 1:199(9):1139-1147. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201805-1011OC. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30522343]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet (London, England). 2020 Oct 17:396(10258):1204-1222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33069326]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMortimer K, Lesosky M, García-Marcos L, Asher MI, Pearce N, Ellwood E, Bissell K, El Sony A, Ellwood P, Marks GB, Martínez-Torres A, Morales E, Perez-Fernandez V, Robertson S, Rutter CE, Silverwood RJ, Strachan DP, Chiang CY, Global Asthma Network Phase I Study Group. The burden of asthma, hay fever and eczema in adults in 17 countries: GAN Phase I study. The European respiratory journal. 2022 Sep:60(3):. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02865-2021. Epub 2022 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 35210319]

Pate CA, Zahran HS, Qin X, Johnson C, Hummelman E, Malilay J. Asthma Surveillance - United States, 2006-2018. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Surveillance summaries (Washington, D.C. : 2002). 2021 Sep 17:70(5):1-32. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss7005a1. Epub 2021 Sep 17 [PubMed PMID: 34529643]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLiu MC, Hubbard WC, Proud D, Stealey BA, Galli SJ, Kagey-Sobotka A, Bleecker ER, Lichtenstein LM. Immediate and late inflammatory responses to ragweed antigen challenge of the peripheral airways in allergic asthmatics. Cellular, mediator, and permeability changes. The American review of respiratory disease. 1991 Jul:144(1):51-8 [PubMed PMID: 2064141]

Riccio MM, Proud D. Evidence that enhanced nasal reactivity to bradykinin in patients with symptomatic allergy is mediated by neural reflexes. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 1996 Jun:97(6):1252-63 [PubMed PMID: 8648021]

Limb SL, Brown KC, Wood RA, Wise RA, Eggleston PA, Tonascia J, Adkinson NF Jr. Irreversible lung function deficits in young adults with a history of childhood asthma. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2005 Dec:116(6):1213-9 [PubMed PMID: 16337448]

Förster-Ruhrmann U, Olze H. [Importance of aspirin challenges in patients with NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease]. HNO. 2024 Apr 10:():. doi: 10.1007/s00106-024-01460-9. Epub 2024 Apr 10 [PubMed PMID: 38597968]

Lee DL, Baptist AP. Understanding the Updates in the Asthma Guidelines. Seminars in respiratory and critical care medicine. 2022 Oct:43(5):595-612. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-1745747. Epub 2022 Jun 21 [PubMed PMID: 35728605]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStanojevic S, Kaminsky DA, Miller MR, Thompson B, Aliverti A, Barjaktarevic I, Cooper BG, Culver B, Derom E, Hall GL, Hallstrand TS, Leuppi JD, MacIntyre N, McCormack M, Rosenfeld M, Swenson ER. ERS/ATS technical standard on interpretive strategies for routine lung function tests. The European respiratory journal. 2022 Jul:60(1):. pii: 2101499. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01499-2021. Epub 2022 Jul 13 [PubMed PMID: 34949706]

Tsuyuki RT, Midodzi W, Villa-Roel C, Marciniuk D, Mayers I, Vethanayagam D, Chan M, Rowe BH. Diagnostic practices for patients with shortness of breath and presumed obstructive airway disorders: a cross-sectional analysis. CMAJ open. 2020 Jul-Sep:8(3):E605-E612. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20190168. Epub 2020 Sep 25 [PubMed PMID: 32978240]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAaron SD, Vandemheen KL, FitzGerald JM, Ainslie M, Gupta S, Lemière C, Field SK, McIvor RA, Hernandez P, Mayers I, Mulpuru S, Alvarez GG, Pakhale S, Mallick R, Boulet LP, Canadian Respiratory Research Network. Reevaluation of Diagnosis in Adults With Physician-Diagnosed Asthma. JAMA. 2017 Jan 17:317(3):269-279. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19627. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28114551]

Coates AL, Wanger J, Cockcroft DW, Culver BH, Bronchoprovocation Testing Task Force: Kai-Håkon Carlsen, Diamant Z, Gauvreau G, Hall GL, Hallstrand TS, Horvath I, de Jongh FHC, Joos G, Kaminsky DA, Laube BL, Leuppi JD, Sterk PJ. ERS technical standard on bronchial challenge testing: general considerations and performance of methacholine challenge tests. The European respiratory journal. 2017 May:49(5):. pii: 1601526. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01526-2016. Epub 2017 May 1 [PubMed PMID: 28461290]

Gauvreau GM, O'Byrne PM, Boulet LP, Wang Y, Cockcroft D, Bigler J, FitzGerald JM, Boedigheimer M, Davis BE, Dias C, Gorski KS, Smith L, Bautista E, Comeau MR, Leigh R, Parnes JR. Effects of an anti-TSLP antibody on allergen-induced asthmatic responses. The New England journal of medicine. 2014 May 29:370(22):2102-10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402895. Epub 2014 May 20 [PubMed PMID: 24846652]

Dhuper S, Chandra A, Ahmed A, Bista S, Moghekar A, Verma R, Chong C, Shim C, Cohen H, Choksi S. Efficacy and cost comparisons of bronchodilatator administration between metered dose inhalers with disposable spacers and nebulizers for acute asthma treatment. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2011 Mar:40(3):247-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.06.029. Epub 2008 Dec 11 [PubMed PMID: 19081697]

Cates CJ, Welsh EJ, Rowe BH. Holding chambers (spacers) versus nebulisers for beta-agonist treatment of acute asthma. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2013 Sep 13:2013(9):CD000052. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000052.pub3. Epub 2013 Sep 13 [PubMed PMID: 24037768]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNewman KB, Milne S, Hamilton C, Hall K. A comparison of albuterol administered by metered-dose inhaler and spacer with albuterol by nebulizer in adults presenting to an urban emergency department with acute asthma. Chest. 2002 Apr:121(4):1036-41 [PubMed PMID: 11948030]

Normansell R, Kew KM, Mansour G. Different oral corticosteroid regimens for acute asthma. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2016 May 13:2016(5):CD011801. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011801.pub2. Epub 2016 May 13 [PubMed PMID: 27176676]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKew KM, Kirtchuk L, Michell CI. Intravenous magnesium sulfate for treating adults with acute asthma in the emergency department. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2014 May 28:2014(5):CD010909. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010909.pub2. Epub 2014 May 28 [PubMed PMID: 24865567]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRovsing AH, Savran O, Ulrik CS. Magnesium sulfate treatment for acute severe asthma in adults-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in allergy. 2023:4():1211949. doi: 10.3389/falgy.2023.1211949. Epub 2023 Jul 28 [PubMed PMID: 37577333]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKnightly R, Milan SJ, Hughes R, Knopp-Sihota JA, Rowe BH, Normansell R, Powell C. Inhaled magnesium sulfate in the treatment of acute asthma. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017 Nov 28:11(11):CD003898. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003898.pub6. Epub 2017 Nov 28 [PubMed PMID: 29182799]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceStefan MS, Nathanson BH, Lagu T, Priya A, Pekow PS, Steingrub JS, Hill NS, Goldberg RJ, Kent DM, Lindenauer PK. Outcomes of Noninvasive and Invasive Ventilation in Patients Hospitalized with Asthma Exacerbation. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2016 Jul:13(7):1096-104. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201510-701OC. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27070493]

Soroksky A, Stav D, Shpirer I. A pilot prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of bilevel positive airway pressure in acute asthmatic attack. Chest. 2003 Apr:123(4):1018-25 [PubMed PMID: 12684289]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNair P, Milan SJ, Rowe BH. Addition of intravenous aminophylline to inhaled beta(2)-agonists in adults with acute asthma. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2012 Dec 12:12(12):CD002742. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002742.pub2. Epub 2012 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 23235591]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCremer NM, Baptist AP. Race and Asthma Outcomes in Older Adults: Results from the National Asthma Survey. The journal of allergy and clinical immunology. In practice. 2020 Apr:8(4):1294-1301.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.12.014. Epub 2020 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 32035849]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNardone A, Casey JA, Morello-Frosch R, Mujahid M, Balmes JR, Thakur N. Associations between historical residential redlining and current age-adjusted rates of emergency department visits due to asthma across eight cities in California: an ecological study. The Lancet. Planetary health. 2020 Jan:4(1):e24-e31. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(19)30241-4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31999951]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSong WJ, Lee JH, Kang Y, Joung WJ, Chung KF. Future Risks in Patients With Severe Asthma. Allergy, asthma & immunology research. 2019 Nov:11(6):763-778. doi: 10.4168/aair.2019.11.6.763. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31552713]