Introduction

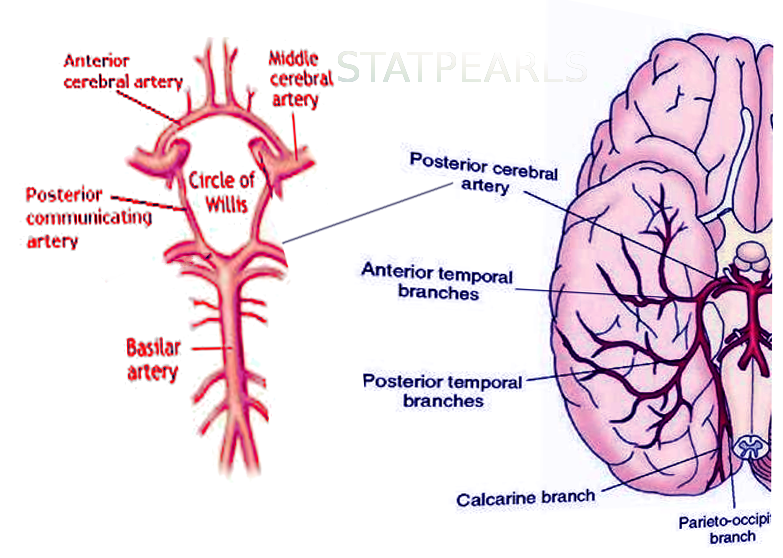

The cerebral circulation is composed of a multitude of arteries that provide oxygenated blood to the brain. The cerebral vasculature is unique because it has a circular ring of anastomosing arteries that provide collateral circulation to the brain, known as the circle of Willis. Both anterior and posterior circulations of the brain are connected by the posterior communicating arteries, which connect the internal carotid arteries on either side to the terminal branches of the basilar artery (posterior cerebral arteries). The posterior cerebral arteries (PCA) arise from the basilar artery 70% of the time, from the posterior communicating arteries 20% of the time, and a mix of the two for the remaining 10%.[1] Because the occipital lobe, the primary visual processing center of the mammalian brain, is mainly supplied by PCA, damage to these vessels can result in a variety of pathology affecting vision.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The PCA courses from the basilar artery towards the occiput around the cerebral peduncle and over the tentorium cerebelli to ultimately supply the occipital lobe, posteromedial temporal lobes, midbrain, thalamus, choroid plexus, and part of the lateral and third ventricles.

There are five main segments of the PCA (developed by Krayenbühl and Yasargil):

P1: The P1 segment is located within the interpeduncular cistern and courses from the termination of the basilar artery to the posterior communicating artery, passing over the oculomotor nerve (CN III). This segment gives off small paramedian arteries that supply the rostral midbrain and thalamoperforating arteries, which supply part of the thalamus. It may also give off the artery of Percheron, which is a rare anatomic variant that can supply the thalamus and midbrain bilaterally. Embolism to this anatomic variant may result in bilateral paramedian thalamic lesions. Patients may present with symptoms such as memory impairment, altered sensorium, and vertical gaze palsy. Since these vessels are not visible with conventional vascular imaging, diagnosis may be difficult.

P2: The P2 segment begins at the posterior communicating artery and curves around the ambient cistern of the midbrain, and courses above the tentorium cerebelli. The main branch of this segment is the posterior choroidal artery, but it also gives rise to peduncular perforating arteries that supply the lateral midbrain as well as thalamogeniculate arteries that supply the ventrolateral portion of the thalamus. This segment further subdivides into P2A (anterior) sub-segment located within the crural cistern and P2P (posterior, ambient) sub-segment located in the ambient cistern.

P3: The P3 segment of the PCA refers to the part of the artery that runs through the quadrigeminal cistern. The quadrigeminal cistern not only contains this portion of the PCA but also contains the posterior choroidal arteries, superior cerebellar arteries, the trochlear nerve (CN IV), and a confluence of veins. This segment commonly gives off anterior and posterior inferior temporal arteries.

P4: The P4 segment is the last segment of the PCA, as it ends in the calcarine sulcus. The P4 segment most commonly gives rise to the parieto-occipital branches and the calcarine artery, which supplies areas bordering the calcarine sulcus and the medial surface of the occipital lobe.[2]

P5: The terminal branches of the parieto-occipital and the calcarine arteries are included as the P5 segment.

Embryology

Around the 28th day of development, the internal carotid artery branches into an anterior and posterior division. The anterior division ultimately gives rise to the anterior choroidal artery, the anterior cerebral artery, and the middle cerebral artery (MCA). In turn, the posterior division gives rise to the fetal posterior cerebral artery. During the initial stages of fetal development, the posterior circulation receives almost the entirety of its blood supply from the vertebrobasilar anastomosis. Subsequently, as the contents of the posterior fossa and occipital lobe grow, the posterior circulation becomes progressively independent from the anterior circulation, resulting in obliteration of the anterior-posterior anastomoses, leaving the posterior communicating arteries as the only adult anastomoses between the anterior-posterior circulation.[3] The adult posterior cerebral artery anastomoses with the basilar artery as branches from the fetal posterior cerebral arteries fuse medially to form the distal end of the basilar artery.

If the fetal posterior cerebral artery persists and continues to arise from the internal carotid artery, it may result in a smaller caliber basilar artery. This phenomenon occurs in 10 to 29% of the population and most commonly occurs unilaterally.[4] The persistence of a fetal PCA may further be defined as partial or complete depending on if the P1 segment of the PCA is hypoplastic. Patients with ipsilateral persistence of a fetal PCA are unable to establish leptomeningeal anastomoses between the anterior cerebral artery, middle cerebral artery, and posterior cerebral artery. Thus, patients with an ipsilateral fetal PCA may be particularly susceptible to ischemia due to ICA stenosis or thrombosis.[5]

Physiologic Variants

The combination of hemisensory loss and hemianopia without paralysis is virtually diagnostic of infarction in the PCA territory.

Ocular Disturbances

The most frequent finding in patients with a PCA territory infarct is contralateral hemianopia. The visual defect often presents as a limitation of vision to one side, and patients usually recognize that they must focus extra attention on the hemianopic field. When given pictures or written material, patients with hemianopia due to occipital lobe infarction can see and interpret visual stimuli normally, although it may take somewhat longer to explore the hemianopic visual field. Some patients will be able to accurately report motion or the presence of objects in their hemianopic field but will not be able to identify the nature, location, or color of those objects. When the central portion of the visual field is spared, the term is "macular-sparing"; sparing of this portion of the visual field is due to collateral circulation provided by the MCA. A superior quadrantanopia may also occur if the infarct solely involved the lingual gyrus, the lower portion of the calcarine fissure. Conversely, an inferior quadrantanopia may result if the lesion affects the cuneus on the upper portion of the calcarine fissure.

However, when the full territory of the posterior cerebral arteries is involved, patients may experience visual neglect along with their hemianopia due to the involvement of the non-dominant parietal lobe. Contrarily, if the lesion involves circulation to the dominant parietal cortex, patients may also exhibit alexia without agraphia, in which they would be able to write but unable to read.[6]

Sensorimotor Abnormalities

Since the posterior cerebral arteries contribute to the arterial supply of the lateral thalamus, PCA territory ischemia can result in sensory deficits such as paresthesias in the face, limbs, and trunk. Rarely, occlusion of the proximal portion of the PCA causes hemiplegia, which may be attributable to infarction of the lateral midbrain. Due to the proximal course of the PCA close to the cerebral peduncles, the involvement of the corticospinal tract in the lateral midbrain is responsible for this hemiplegia.

Left PCA Territory Symptoms and Signs

Because the left parietal cortex is usually dominant, left PCA infarct would result in alexia without agraphia, anomic aphasia, visual agnosia, anomic aphasia, or transcortical sensory aphasia, and Gerstmann syndrome (acalculia, agraphia, finger agnosia, and right-left disorientation).[7] Some patients with left PCA territory infarction experience difficulty in understanding the nature and use of objects presented visually (visual agnosia). They can copy or trace objects with their fingers, demonstrating the preservation of visual perception; they can name objects placed in their hand and explored by touch or when described to them verbally.

Right PCA Territory Symptoms and Signs

Because the right parietal cortex is usually not the dominant hemisphere, infarcts in the right PCA territory are often accompanied by prosopagnosia, which is difficulty in recognizing familiar faces. Disorientation to place with an inability to recall routes or to read or visualize the location of places on maps is also common. Patients suffering from right occipitotemporal infarcts also may have difficulty visualizing how a given object or person appears. Dreams may be devoid of visual imagery. Visual neglect may also present, in which a patient ignores the left side of his visual field.

Specific clinical findings associated with the vascular territory may be summarized below:

Unilateral PCA Infarct

- Only occipital lobe-->contralateral homonymous hemianopia with macular sparing

- Dominant occipital lobe + the splenium of the corpus callosum-->homonymous hemianopia + alexia without agraphia

- Ventral occipital cortex + infracalcarine--> achromatopsia (contralateral loss of color differentiation) + superior quadrantanopia

- Infracalcarine/Meyer loop/temporal lobe--> superior quadrantanopia

- Supracalcarine/Optic radiation--> Inferior quadrantanopia

Bilateral PCA infarct

- Both occipital lobes--> cortical blindness + Anton syndrome

- Anton syndrome: cortical blindness with denial of blindness, visual hallucinations, and confabulations[8]

PCA-MCA watershed infarct

A watershed infarct occurs in distal branches of large arteries when there is a decrease in perfusion or hypovolemia. An infarct at the PCA-MCA usually leads to ischemia in two regions:

- Bilateral occipitotemporal border zone--> prosopagnosia; an inability to recognize familiar faces and/or interpret facial expressions but can identify with speech or unique features such as glasses, tattoos, or piercings, etc.

- Bilateral occipito-parietal border zone--> Balint syndrome; optic ataxia (inability to reach targets with visual guidance), oculomotor apraxia (inability to volitionally direct gaze), and simultagnosia (inability to synthesize objects within a visual field)

- Unilateral left temporal-parietal border zone--> transcortical sensory aphasia; fluent speech and repetition, but impaired comprehension.

Surgical Considerations

In traumatic head injury with transtentorial herniation, the posterior cerebral arteries are at risk for compression. These vessels should be preserved during amygdalohippocampectomy surgeries.

Clinical Significance

The mainstay in the evaluation of acute stroke is a non-contrast-enhanced computed tomogram (CT) scan.

A stroke can categorize as acute (less than 24 hours), subacute (24 hours to five days), or chronic (weeks). Due to the cytotoxic edema in acute stroke, one would visualize hyper-attenuation with effacement of cortical sulci and lack of differentiation between the gray and white matter. Conversely, vasogenic edema is present with subacute stroke, and it is during this stage in which mass effect and subsequent herniation are of the highest risk. Chronic strokes are also hypo-attenuating and demonstrate the loss of brain tissue.[9]

A CT angiogram may also help to visualize the entire cerebral circulation beginning from the aortic arch to determine the exact etiology of the stroke. However, CTA also carries the same limitations as a CT with contrast due to its use of contrast; this is a beneficial technique to determine etiologies such as aneurysms or arteriovenous malformations.

Although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the gold standard for the detection of various pathologies, they are not routinely used for acute stroke for a variety of reasons. MRIs take much longer to complete than CT scans and are not good at detecting the intracellular edema seen in the acute phase of a stroke. One huge exception to this is diffusion-weighted MRI, which can still illustrate the acute phase of stroke and can be completed fairly quickly at some centers. Standard MRI images such as T1 and T2 imaging, however, can detect sub-acute stroke as they can visualize vasogenic edema.

Although stroke of the anterior circulation of the brain is far more common, 20% of ischemic events in the brain involve the posterior circulation (vertebrobasilar system). When an ischemic event does occur in the posterior circulation, it is most commonly due to atherosclerosis, embolism, or arterial dissection.

Atherosclerosis

Large vessel atherosclerotic disease most commonly results in thromboembolism but can also cause hemodynamic instability leading to ischemia. Large vessel atherosclerotic disease was responsible for 35% of posterior circulation strokes, while small vessel disease accounted for only 13% of these strokes in a recent meta-analysis.[4] Large vessel atherosclerosis in the posterior circulation usually presents in the vertebral arteries, but fatty streaks, fibrous plaques, and arterial calcification are still far less common in the vertebral arteries than in the internal carotid arteries.

Cardioembolism

Unlike the vertebral and basilar arteries, ischemia, specifically in the PCA, is potentially attributable to embolism from the heart, aorta, or vertebral arteries. Since a vast majority of the cerebral blood flow goes through the internal carotid arteries, only 20% of cardiac emboli end up in the posterior circulation. Cardioembolism may result from a variety of causes, which include prosthetic heart valves, atrial fibrillation, valvular disease, dilated cardiomyopathy, and congestive heart failure.

Arterial Dissection

Arterial dissection is a very uncommon cause of a posterior circulation stroke and does not present in the PCA without concomitant involvement of the basilar or vertebral arteries; this is because dissection in the posterior circulation is due to cervical trauma. This condition can present in young active adults or patients in a recent motor vehicle accident. Carotid artery dissections account for 15% of strokes occurring in the young adult population (15 to 49 years old).[4] Characteristic features of patients due to a dissection include a history of trauma, neck pain, and an associated occipital headache. In comparison to dissections involving the internal carotid artery, dissections involving the posterior circulation more frequently correlate with a subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Treatment for ischemic stroke includes the use of tPA (tissue plasminogen activator) within 3 to 4.5 hours since onset and with absolute confidence that there was no hemorrhagic etiology. Patients will also initiate pharmacologic therapy, including antiplatelet agents such as aspirin or clopidogrel. Additional variables requiring control include blood pressure, blood sugar, and lipids. Nevertheless, physicians must always treat the underlying cause (atrial fibrillation, etc.).[10]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Diagram of the Posterior Cerebral Artery and its Branches. Each number corresponds to the following neuroanatomy: 1) basilar artery; 2) superior cerebellar artery; 3) posterior cerebral artery; 4) thalamic subthalamic arteries; 5) posterior communicating artery; 6) internal carotid artery; 7) polar artery of thalamus; 8) posterior choroidal artery; 9) thalamogeniculate artery; 10) anterior inferior temporal artery; 11) posterior inferior temporal artery; 12) occipitotemporal artery; 13) calcarine arteries; and 14) occipitoparietal artery.

Contributed by O Kuybu, MD

References

Kuybu O, Tadi P, Dossani RH. Posterior Cerebral Artery Stroke. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30335329]

Párraga RG, Ribas GC, Andrade SE, de Oliveira E. Microsurgical anatomy of the posterior cerebral artery in three-dimensional images. World neurosurgery. 2011 Feb:75(2):233-57. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2010.10.053. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21492726]

Menshawi K, Mohr JP, Gutierrez J. A Functional Perspective on the Embryology and Anatomy of the Cerebral Blood Supply. Journal of stroke. 2015 May:17(2):144-58. doi: 10.5853/jos.2015.17.2.144. Epub 2015 May 29 [PubMed PMID: 26060802]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNouh A, Remke J, Ruland S. Ischemic posterior circulation stroke: a review of anatomy, clinical presentations, diagnosis, and current management. Frontiers in neurology. 2014:5():30. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00030. Epub 2014 Apr 7 [PubMed PMID: 24778625]

Capone S, Shah N, George-St Bernard RR. A Fetal-type Variant Posterior Communicating Artery and its Clinical Significance. Cureus. 2019 Jul 2:11(7):e5064. doi: 10.7759/cureus.5064. Epub 2019 Jul 2 [PubMed PMID: 31516775]

Sharma B, Handa R, Prakash S, Nagpal K, Bhana I, Gupta PK, Kumar S, Sisodiya MS. Posterior cerebral artery stroke presenting as alexia without agraphia. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2014 Dec:32(12):1553.e3-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.04.046. Epub 2014 Apr 26 [PubMed PMID: 24935413]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBenton AL. Gerstmann's syndrome. Archives of neurology. 1992 May:49(5):445-7 [PubMed PMID: 1580804]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceM Das J, Naqvi IA. Anton Syndrome. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30844182]

Birenbaum D, Bancroft LW, Felsberg GJ. Imaging in acute stroke. The western journal of emergency medicine. 2011 Feb:12(1):67-76 [PubMed PMID: 21694755]

Strambo D, Bartolini B, Beaud V, Marto JP, Sirimarco G, Dunet V, Saliou G, Nannoni S, Michel P. Thrombectomy and Thrombolysis of Isolated Posterior Cerebral Artery Occlusion: Cognitive, Visual, and Disability Outcomes. Stroke. 2020 Jan:51(1):254-261. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.026907. Epub 2019 Nov 13 [PubMed PMID: 31718503]