Introduction

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) is an autosomal recessive disorder resulting from the deficiency of one of the enzymes required to synthesize cortisol in the adrenal cortex. Over 90% of CAH cases are caused by 21-hydroxylase deficiency, which is the most common cause of genital atypia in young children.[1][2][3][4] As 21-hydroxylase deficiency CAH is often undiagnosed in affected males until they develop severe adrenal insufficiency, which can be life-threatening if not promptly treated, the United States and many other countries have implemented newborn screening programs that measure 17-hydroxyprogesterone concentrations. These programs can detect almost all infants with classic (severe) CAH and some infants with milder variants of CAH. Although false-negative results are rare, false-positive results can be observed in premature infants; therefore, serial measurements of 17-hydroxyprogesterone are advised for premature infants. A positive newborn screening result for CAH must be confirmed with a second plasma sample (17-hydroxyprogesterone), and serum electrolytes should be measured. The classic (severe) form can cause adrenal insufficiency in both genders and is often associated with genital atypia in female (46XX) infants. In contrast, the nonclassic (milder) form may lead to infertility in females.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

CAH is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by a deficiency in 21-hydroxylase. The activity of this enzyme is mediated by cytochrome p450c21 found in the endoplasmic reticulum.[5][6][7] The loss or impairment of CYP21A2 leads to the impaired production of the enzyme cytochrome p450c21. This gene lies within the class III region of the human major histocompatibility complex on chromosome 6 (6p21.3). The gene structure contains both an active gene, CYP21A2, and a pseudogene, CYP21A1P. More than 90% of mutations causing 21-hydroxylase deficiency involve recombination between CYP21A2 and CYP21A1P; over 200 mutations are known.[4]

Around one-fourth of pathologic molecular changes are small deletions that produce null variants, which entirely prevent the synthesis of a functional protein. Other mutations are missense mutations that yield enzymes with 1% to 50% of normal activity. Patients are often compound heterozygotes with different types of mutations where one allele is less severely affected than the other; in these cases, the severity of disease expression is primarily determined by the activity of the less severely affected allele. The severity of the disease correlates well with the wild-type genotype and the expected residual activity of the genotype (mutated gene) carried by an affected individual.

Approximately 10% of individuals with 21-hydroxylase deficiency CAH have CAH-X syndrome, in which the gene TNXB (protein tenascin) is also mutated as part of a contiguous gene deletion. These patients often have characteristics of Ehler-Danlos syndrome in addition to CAH. Molecular genetic testing of the CYP21 gene is available and can detect common mutations and deletions in various forms in up to 95% of affected individuals.

Epidemiology

CAH occurs among all ethnic groups, and its prevalence appears to be increasing.[8] The global incidence of classical 21-hydroxylase-deficient CAH is approximately 1 in 15,000 to 20,000 births in Western countries. However, a multicentric newborn screening study in India reported a much higher prevalence of approximately 1:6000, possibly due to the high rate of consanguineous marriages in this region. Approximately 75% of the affected infants have the salt-wasting form, whereas 25% have the simple virilizing form.[5][9][10][11] The nonclassic form of CAH has a prevalence of approximately 1 in 1000 in the general population but may be as common as 1 in 100 to 200 in specific ethnic groups.

Pathophysiology

Steroid 21-hydroxylase (CYP21, P450c21) is a cytochrome P-450 enzyme in the endoplasmic reticulum. This enzyme is an essential component of an enzyme complex required to synthesize cortisol and aldosterone in the zona fasciculata and zona glomerulosa of the adrenal cortex, respectively. The enzyme hydroxylates 17-hydroxyprogesterone to 11-deoxycortisol, a precursor of cortisol, and progesterone to deoxycorticosterone, a precursor of aldosterone. Both cortisol and aldosterone are deficient in the disease's most severe, salt-wasting form.[12] Cortisol deficiency leads to feedback stimulation of adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH) from the pituitary gland. This increased ACTH can result in hyperplasia of the adrenal cortex, accumulation of cortisol precursors, and diversion of cascade reactions that produce excess androgens. This cascade leads to clinical manifestations in infants, including hyperpigmentation due to high ACTH, failure to thrive, electrolyte imbalances, acidosis, shock resulting from adrenal insufficiency, and virilization of 46XX infants due to high androgen levels.

In addition to 17-hydroxyprogesterone, 21-deoxycortisol can be used to screen for 21-hydroxylase deficiency CAH. This hormone is formed by 11-hydroxylase activity on accumulated 17-hydroxyprogesterone. 21-Deoxycortisol is considered a more reliable screening marker compared to 17-hydroxyprogesterone because its concentrations are less affected by gestational age and timing of sample collection, and it is a more specific marker to diagnose 21-hydroxylase deficiency CAH.[13]

11-Hydroxy androgens are another group of significant androgens associated with 21-hydroxylase deficiency. These androgens include 11-beta-hydroxy androstenedione, 11-keto-hydroxy androstenedione, and 11-ketotestosterone, which are formed by the activity of 11-beta-hydroxylase, 11-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-2, and aldo-keto reductase (AKR1C3) enzymes on androstenedione, respectively.

History and Physical

Classification of 21-hydroxylase Deficiency

21-hydroxylase deficiency is classified based on the severity of the disease and the time of onset into 2 forms—classic and nonclassic.

Classic 21-hydroxylase deficiency: Classic 21-hydroxylase deficiency is further classified into 2 types—salt wasting and simple virilizing. The salt-wasting form is the most severe.

- Salt-wasting congenital adrenal hyperplasia (defect in cortisol and aldosterone biosynthesis)

- Approximately 75% of patients with classic 21-hydroxylase deficiency present with the salt-wasting form, which is the most severe type of the disease.[4] This form is often associated with large gene deletions or intron mutations that result in no enzyme activity.

- Clinicians recognize the condition in 46XX infants earlier in the neonatal period due to ambiguous genitalia. In contrast, 46XY infant males typically have normal genitalia and may present with nonspecific symptoms such as vomiting, dehydration, and poor feeding at ages 1 to 3 weeks. Hence, the diagnosis in boys can be delayed or missed.

- Females are exposed to high systemic levels of adrenal androgens starting from the seventh week of gestation. Thus, they are born with ambiguous genitalia, which may include a large clitoris, rugated and potentially fused labia majora, and a common urogenital sinus instead of a separate urethra and vagina. The uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries are normally formed, but Wolffian ducts are not developed.

- Aldosterone plays a significant role in regulating sodium homeostasis. In untreated patients, excessive renal sodium excretion leads to hypovolemia and hyperreninemia. These patients cannot excrete potassium efficiently and are prone to hyperkalemia, especially during infancy. In addition, accumulated steroid precursors may directly antagonize mineralocorticoid receptors and exacerbate mineralocorticoid deficiency, particularly in untreated patients. Progesterone is known to have anti-mineralocorticoid effects.

- High levels of glucocorticoids are necessary for the normal development of the adrenal medulla and the expression of enzymes required for catecholamine synthesis. Therefore, patients with the salt-wasting type may also have catecholamine deficiency. The combined deficiency of cortisols and aldosterones leads to hyponatremic dehydration and shock in inadequately treated patients. Infants presenting with poor weight gain, poor feeding, hypovolemia with hyponatremia, and hyperkalemia should be evaluated for possible CAH.

- Postnatally, in untreated or inadequately treated patients, long-term exposure to high androgen levels promotes rapid somatic growth and advanced bone age. Linear growth can be affected even with close therapeutic monitoring. Pubic and axillary hair may develop early. Clitoral growth may continue in girls. Young boys may have penile growth despite having small testes. Long-term exposure to androgens may activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, leading to centrally mediated precocious puberty.

- Girls may present with oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea in adolescence. With advancements in surgical, medical, and psychological treatments, more women with 21-hydroxylase deficiency are now able to complete pregnancies and give birth successfully.

- The prevalence of testicular adrenal rest tumors (TARTs) in boys with classic CAH varies depending on the timing of diagnosis, disease control, and age range. A recent multicentric European study reported the prevalence of TARTs at 38%.[14] The authors concluded that delayed detection of CAH and poor disease control in early life are associated with a higher prevalence of TARTs. Another review showed a varied prevalence of 14% to 86% in different studies, depending on the age and genotype of the study population, with an average prevalence of 37%.[15] These so-called TARTs are benign and are often related to suboptimal therapy. These tumors typically decrease in size after the optimization of glucocorticoid therapy. Testicular masses in boys with classic CAH are generally bilateral, smaller than 2 cm in diameter, and not palpable but detectable using ultrasound.

- Simple virilizing congenital adrenal hyperplasia (normal aldosterone biosynthesis)

- Approximately 25% of patients with classic 21-hydroxylase deficiency present with simple virilization without salt wasting. This form typically results from point mutations that cause amino acid substitution, leading to low but detectable enzyme activity. As a result, aldosterone secretion remains adequate, but cortisol levels are decreased.

- Females present at birth with ambiguous genitalia. Without newborn screening, affected boys are diagnosed during childhood when signs of androgen excess, such as pubic hair development or rapid growth, emerge. A later diagnosis is associated with short stature and greater difficulty in achieving hormonal control. Diagnostic criteria remain the same for salt-wasting CAH and simple virilizing CAH (Please refer to the Evaluation section for more information).

Nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia 21-hydroxylase deficiency (mild form): The nonclassic or late-onset form is much more common, occurring in 0.1% to 0.2% of the general White population and 1% to 2% of Ashkenazi Jews.[8] Females with the nonclassic form may be compound heterozygotes with a classic mutation and variant allele or homozygotes with 2 variant alleles, allowing 20% to 60% of normal enzymatic activity.

Compound heterozygote females have a less severe phenotype, and their clinical presentation varies. Some may exhibit mild biochemical abnormalities without clinically significant endocrine disorders.

Patients with the nonclassic form have normal levels of cortisol and aldosterone at the expense of mild-to-moderate overproduction of sex hormone precursors. Newborn screening can detect nonclassic cases, but most are missed because of relatively low baseline levels of 17-hydroxyprogesterone.

In females, hirsutism is the common symptom at presentation, followed by oligomenorrhea and acne. Thus, nonclassic 21-hydroxylase deficiency and polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) may present in similar ways. A baseline morning 17-hydroxyprogesterone measurement during the follicular phase, combined with cosyntropin stimulation testing, is necessary for all females presenting with features of PCOS.[16] Early pubarche and advanced bone age are other presentations for both genders.

Although the classification of salt-wasting CAH, simple virilizing CAH, and nonclassic CAH 21-hydroxylase deficiency helps in understanding the severity of the disease, this demarcation is being obscured as more experience is gained. This condition is a continuous spectrum of manifestations from severe salt wasting at one end to a milder variant presenting as early adrenarche only at the other end rather than being watertight compartments of the above-said classification.

Evaluation

Diagnostic Approach to 21-Hydroxylase Deficiency and Associated Tests

- Newborn screening programs routinely test for 21-hydroxylase deficiency.

- Levels of 17-hydroxyprogesterone are very high (cutoff of >1000 ng/dL, but frequently >5000-10,000) in patients with the classic form.[8]

- Although liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) is the current standard of care, immunoassays are still used in many parts of the world and are a source of false-positive results. Therefore, either second-tier LC-MS/MS or cosyntropin stimulation testing should be performed before initiating steroids in cases of mild elevation of 17-hydroxyprogesterone. Other than this, if 17-hydroxyprogesterone levels are ambiguous (200-1000 ng/dL) or other enzyme defects, such as 11-beta-hydroxylase, 3-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, or p450 oxidoreductase deficiency, are suspected, cosyntropin stimulation testing should be performed. This test evaluates the complete adrenal profile, including measurements of 17-hydroxyprogesterone, cortisol, 11-deoxycorticosterone, 11-deoxycortisol, 17-hydroxypregnenolone, dehydroepiandrosterone, and androstenedione. Samples can be obtained immediately before and 60 minutes after administering 0.25 mg of cosyntropin, a synthetic ACTH. Cosyntropin administration provides a pharmacologic stimulus to the adrenal glands, maximizing hormone secretion. A stimulation test is typically unnecessary to diagnose a typical 21-hydroxylase deficiency CAH with a concordant clinical profile and unambiguously high 17-hydroxyprogesterone.

- Hyperkalemia, hyponatremia, low aldosterone, and high plasma renin activity, particularly the ratio of plasma renin activity to aldosterone, are markers of impaired mineralocorticoid synthesis.

- In infants with ambiguous genitalia, a karyotype can be used to establish the chromosomal sex.

- A pelvic ultrasound should be performed to assess the uterus or associated renal anomalies.

- Urogenitography can be used to define the anatomy of the internal genitalia.

Molecular Genetic Analysis

- In most cases, hormonal assessment combined with clinical presentation is sufficient for diagnosing this condition, and molecular genetic analysis is part of the evaluation in only selected individuals. Molecular testing may be helpful in situations such as initiating steroid treatment before establishing a firm diagnosis, providing genetic counseling for future pregnancies, and addressing diagnostic dilemmas.[5] However, caution is advised when ordering and interpreting molecular genetic tests due to the complexity of CYP21A2 mutations, which are often influenced by gene duplications, deletions, and the presence of the CYP21A1P pseudogene, frequently requiring parental testing.

- In cases of late presentation, a bone age study can be valuable, particularly in patients with precocious pubic hair.

Treatment / Management

Acute Adrenal Crisis

Despite the significant reduction in infant mortality due to widespread newborn screening programs for CAH, adrenal crisis remains the leading cause of death among individuals with CAH. Therefore, it is crucial for every clinician managing this condition to understand the importance of administering stress doses of steroids during illnesses.

- An adrenal crisis is a medical emergency requiring immediate intervention.

- Initial management should involve stress doses of intravenous (IV) or intramuscular hydrocortisone at 50 to 100 mg/m2 or a neonatal dose of 25 mg, followed by 100 mg/m2/d q 6 hourly. Steroids should be administered as early as possible, concomitant with IV fluid treatment.

- Fluid resuscitation: An IV bolus of isotonic sodium chloride solution (20 mL/kg) should be promptly administered, with repeated boluses as needed.

- Dextrose should be administered if the patient is hypoglycemic, and the patient must be rehydrated with dextrose-containing fluid after the bolus dose to prevent hypoglycemia.

- Central access, vasopressors, and higher glucose concentrations may be required in profoundly ill patients.

- Life-threatening hyperkalemia may require additional therapy with potassium-lowering resins, IV calcium, insulin, and bicarbonate.

Positive Newborn Screen

Newborn screening for CAH is routinely performed in all 50 states of the United States and at least 40 other countries.[5][17][18](A1)

- A positive newborn screening test for CAH must be confirmed with a second plasma sample of 17-hydroxyprogesterone, and serum electrolytes should be measured.

- After obtaining the confirmatory blood sample, treatment with glucocorticoids—and mineralocorticoids if needed—should be promptly initiated in all infants suspected of having CAH to prevent the potentially life-threatening manifestations of an adrenal crisis.

- If the clinician chooses not to initiate treatment while awaiting confirmatory steroid hormone measurements, serum electrolytes should be measured daily.

- A pediatric endocrinologist should treat these patients.

Long-Term Management

The goals of therapy are as follows:

- To replace deficient glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids, ensuring the maintenance of normal plasma volume and physiological balance.

- To reduce excessive androgen secretion from the adrenal glands, enabling the normal growth and achievement of adult height within the normal range, gender-concordant pubertal development, sexual function, and fertility.

- To minimize exposure to glucocorticoids in adulthood and reduce the adverse outcomes associated with supraphysiological steroid doses, control of adrenal-derived androgens is typically relaxed after adult height is reached.[8]

Glucocorticoid replacement:

- Cortisol replacement: Oral hydrocortisone is administered in 3 divided doses of 10 to 20 mg/m2/d.

- Patients with classic 21-hydroxylase deficiency require long-term glucocorticoid treatment to inhibit excessive secretion of CRH and ACTH and to reduce the abnormally high serum concentrations of adrenal androgens.

- Hydrocortisone is the preferred treatment due to its short half-life and minimal impact on growth suppression.

- Treatment efficacy is best assessed by monitoring morning ACTH, 17-hydroxyprogesterone, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, and androstenedione. Although 17-hydroxyprogesterone levels are still higher than normal, a target range of 500 to 1000 ng/dL helps avoid the adverse effects of overtreatment. Once the initial management plan is implemented with close monitoring, monitoring frequency should be every 3 months until 18 months and then every 4 months from 18 months until growth is complete. Children should also have an annual bone age radiograph and careful monitoring of linear growth.

- Older children and adolescents, where growth is complete, may be treated with prednisone (5 to 7.5 mg daily in 2 divided doses) or once-daily dexamethasone (0.25 to 0.5 mg).

- In adults, in addition to the aforementioned hormonal and clinical monitoring, annual assessments of blood pressure, body mass index, and Cushingoid features should be performed.

Mineralocorticoid replacement:

- Infants born with the salt-wasting form of 21-hydroxylase deficiency require mineralocorticoid replacement, typically with fludrocortisone (0.05 to 0.2 mg daily, but occasionally, some patients may require up to 0.4 mg/d). Due to increased mineralocorticoid sensitivity in the later half of infancy, fludrocortisone doses are typically reduced.

- The sodium content in human milk or most infant formulas is about 8 mEq/L, which is insufficient to compensate for sodium losses in these infants. Therefore, salt supplementation during infancy is part of the treatment (1 to 2 g sodium chloride; each gram of sodium chloride contains 17 mEq of sodium).

- Plasma renin activity levels may be used to monitor the effectiveness of mineralocorticoid and sodium replacement. Hypotension, hyperkalemia, and elevated renin levels suggest the need to increase the dose, whereas hypertension, tachycardia, suppressed plasma renin activity, and hypokalemia production are signs of overtreatment.

- Adequate replacement with fludrocortisone helps to reduce steroid doses, as it reduces ACTH drive stimulated by hypovolemia and arginine vasopressin release, but excessive increase in fludrocortisone dosage may retard growth.

Nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia treatment: In children with early pubarche and rapid progression of puberty with bone age advancement and in adolescents with overt virilization, steroid treatment is often necessary. In adult women, hirsutism and infertility are indications for treatment (if the patient desires). Hydrocortisone (15-20 mg) in 3 divided doses is given before conception and continued through gestation to reduce the risk of miscarriage. After fertility needs are met, hirsutism and acne can be treated by oral contraceptive pills with or without spironolactone.

In previously treated patients, hydrocortisone treatment is continued until growth is complete, after which treatment can be discontinued.

Stress management advice: As with other adrenal insufficiency conditions, families should be taught about stress-dosing to avoid adrenal crises during illnesses, such as fever >38.5 °C, gastroenteritis with dehydration, major surgery requiring anesthesia, or trauma. Typically, a 2- to 3-fold daily dose of glucocorticoid is sufficient. Increased fluid intake and frequent ingestion of simple and complex carbohydrates are encouraged to prevent dehydration and hypoglycemia. Intramuscular injection of hydrocortisone (50–100 mg/m2) should be given if oral intake is not possible. Patients should be given medical identification tags.

In nonclassic CAH, stress doses are only necessary when cosyntropin-stimulated cortisol is less than 14 to 18 µg/dL.

Treatment of testicular adrenal rest tumors: Glucocorticoid intensification is required to reduce TART size in adolescents and adult males. Twice-daily dosing of dexamethasone is often necessary. Surgical excision of large confluent TARTs is required frequently for fibrotic elements.

Treatment during pregnancy: Adequate disease control typically leads to successful conception. As dexamethasone crosses the placenta, hydrocortisone or prednisolone should be used during pregnancy. Concordant to any other case of primary adrenal insufficiency, an increase of 20% to 40% in steroid dose is required during the second and third trimesters. Stress dosing should be administered during labor and delivery.

Surgical care: Infants with ambiguous genitalia require a surgical evaluation and, if needed, plans for corrective surgery. The risks and benefits of surgery should be fully discussed with the parents of affected females (Please refer to the Surgical Oncology for more information).

Newer Treatment Options

Currently available standard glucocorticoid therapy often fails to control excess androgen production and risks supraphysiological steroid exposure to affected individuals. Therefore, there is an unmet need for newer therapies that can prevent excessive androgen production without exposing individuals to higher doses of steroids.

- Modified-release hydrocortisone was studied in a recent phase-3 trial in adults.[19] This study did not achieve its primary outcome of better control of 24 hours of 17-hydroxyprogesterone at 24 weeks. However, it showed promise in dose reduction at an 18-month extension, patient-reported benefits of restoration of menses, and a higher number of pregnancies.

- Continuous subcutaneous hydrocortisone infusion (CSHI) was studied in a phase 2 trial in difficult-to-treat adults.[20] Compared to baseline, 6 months of CSHI decreased morning and 24-hour area under the curve 17-hydroxyprogesterone, androstenedione, ACTH, and progesterone. In addition, it improved bone turnover markers and quality of life questionnaire scores.

- Nevanimibe, a potent inhibitor of sterol O-acyltransferase-1, inhibits the esterification of cholesterol and steroid synthesis from the adrenal cortex. In a phase 2, single-blind dose titration study, it reduced 17 OH-P, but its further development was halted due to insufficient efficacy.[21][22] (B2)

- Abiraterone, a CYP17A1 inhibitor, decreased androgen production from elevated precursors in a phase 1 dose-escalation study in adult females, which may be a potential adjunct to current therapy.[23] A phase 1-2 study in children is underway with the same goals.

- Crinecerfont, an oral corticotropin-releasing factor type 1 receptor antagonist, was studied in recent phase 3 randomized placebo-controlled trials in adults and children.[24][25] This drug was safe and efficacious in reducing steroid doses and showed better control of androstenedione in both studies.

- Atumelnant, an oral melanocortin type 2 receptor (ACTH receptor) antagonist, is being studied in a dose-finding open-label phase 2 study.[26] Initial findings suggested a profound and sustained decrease in the participants' morning androstenedione and 17-hydroxyprogesterone.

- Lu AG13909, an ACTH monoclonal antibody available in IV formulation, is being studied in a phase 1, open-label study to assess its effects on morning 17-hydroxyprogesterone, androstenedione, and ACTH levels (NIHR. UCLH patient first in world to receive a new investigational drug in a phase 1 trial).

- BBP-631, a gene-based therapy currently in early-stage development, aims to treat the condition most physiologically by promoting endogenous cortisol production by the adrenals (bridgebio. BridgeBio Pharma Reports Topline Results from Phase 1/2 Trial of Investigational Gene Therapy for Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH)).

Differential Diagnosis

Although features of adrenal insufficiency in infancy, with or without genital atypia, should prompt a workup for CAH, it is essential to consider other conditions that may mimic CAH at different stages of life.

- 46XX virilized females: CAH due to 11-beta-hydroxylase and 3-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase deficiency

- Primary adrenal insufficiency: Adrenal hypoplasia congenital, autoimmune adrenal insufficiency, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage, and familial glucocorticoid deficiency

- Other causes of hyperkalemia or hyponatremia: Hypoaldosteronism and pseudohypoaldosteronism (genetic or acquired renal causes)

- Genital atypia: Other causes of disorders of sex development include placental aromatase deficiency and defects in androgen synthesis or action.

- Oligomenorrhea or amenorrhoea with hyperandrogenism or infertility: PCOS.

Surgical Oncology

Surgical Treatment

In 46XX children with classic CAH who are raised as girls, surgical intervention is often required to reduce clitoromegaly and correct posterior fusion to allow for penovaginal intercourse. A retrospective analysis from Turkey showed comparable anatomical and cosmetic outcomes for surgeries performed before versus after 2 years. However, the early surgery cohort demonstrated an increased need for repeated interventions and decreased parental satisfaction.[27]

Sexual function is another concern in females undergoing genitoplasty. A systematic review involving around 1200 patients showed despite the majority having satisfactory surgical outcomes, only around half of them reported comfortable intercourse and a significant proportion had impaired sexual function scores.[28] A European registry-based study involving girls who underwent surgery during early childhood showed that around three-fourths of patients preferred feminizing surgery during infancy or early childhood. Around 60% described the positive impact of surgery, whereas approximately 10% expressed a negative opinion. Around one-third of patients reported dissatisfaction with their sexual life.[29]

Another retrospective Swedish study involving women with CAH showed that approximately 40% each preferred early surgery or had no preference regarding timing, whereas about 20% preferred to have delayed surgery.[30]

In conclusion, the timing of surgery (early versus late) is an active research area. However, in today's time, many experts or human rights organizations advocate for delayed surgery because of the need for repeated interventions, the risk of gender identity disorder later, and, very importantly, legal concerns when the child is not involved in decision-making. Parents' rights to make decisions regarding their child's care must be respected. Until more data are available, healthcare providers should provide all relevant information and discuss controversies regarding early versus late surgery with the parents to help them make an informed decision.[31]

Bilateral adrenalectomy for CAH is controversial and should be considered only in select cases where medical therapy has failed, particularly in rare instances of adult females with salt-wasting CAH and infertility. The potential risk of noncompliance must also be considered before surgery.

Prognosis

Patients with CAH have higher mortality rates compared to controls, with mortality rates ranging from 1.5 to 5 times that of the control population. Adrenal crisis is the most common culprit.[32] Written education on stress-dose steroids and their timely administration is crucial and cannot be overemphasized.

Children who have CAH with suboptimal control often are tall in early childhood but ultimately are short in adulthood. Recent data suggest that patients born with CAH are about 10 cm shorter than their parentally based targets. The primary factors contributing to this include advanced bone age and central precocious puberty caused by androgen excess, leading to early epiphyseal fusion. In addition, glucocorticoid therapy can suppress growth and diminish the final height. Experimental treatments involving growth hormone and luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone analog to delay puberty have been reported to result in an average height gain of 7.3 cm.[33][34][35] Despite normal bone mineral densities, individuals with CAH are at an increased risk of fractures, necessitating close monitoring of bone health.[36]

Primary and secondary gonadal failure due to TARTs and high adrenal androgens, respectively, compromise fertility in males. Secondary PCOS or suboptimal sexual function can result in compromised fertility in females.

Individuals with CAH are at a higher risk of impaired quality of life due to various factors, including chronic health conditions, short stature, progressive virilization, need for repeated surgeries, undesirable cosmetic outcomes of surgery, and suboptimal sexual function and fertility. The psychological impact of 21-hydroxylase deficiency should be considered.[37]

The prevalence of metabolic abnormalities such as obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and PCOS has been reported to be high due to the disease itself or glucocorticoid treatment.

This disease, its treatment complications, and its long-term consequences are challenging for patients and practitioners. Although newer therapies are more promising, their long-term effectiveness and safety remain to be fully established (Please refer to the Treatment / Management section for more information).

Complications

Complications in CAH are common and stem from the challenges of achieving a delicate balance between inadequate steroid replacement—leading to adrenal insufficiency and ACTH-driven uncontrolled androgen production—and supraphysiological steroid replacement, which causes glucocorticoid-related toxicity. These imbalances can result in short stature, progressive virilization in females, suboptimal fertility, and other complications.

Although current studies have shown conflicting results, there are increasing concerns about decreased bone mineral density and risk of fractures in individuals with CAH due to supraphysiological steroid exposure. Therefore, taking all necessary precautions to maintain steroid doses as low as possible while ensuring adequate disease control is crucial.[36][38][39]

Patients with CAH are at a higher risk of cardiometabolic diseases, including hypertension, obesity, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, impaired glucose homeostasis, increased carotid intima-media thickness, and cardiovascular events. However, most data are available on surrogate markers rather than hard outcomes.[40][41] Practitioners must remain cautious, encourage a healthy lifestyle, and analyze longer-term data for hard outcomes.

The complications of excess mineralocorticoid administration include hypertension and hypokalemia. Aldosterone deficiency may lead to salt wasting with consequent failure to thrive, hypovolemia, and shock.

Due to imperfect management by available treatments, another complication that affects the quality of life in males is TART, which can lead to obstructive infertility. Typically, this complication arises during the second decade of life but may also be present in the first decade if disease management remains poor. Yearly testicular ultrasound screening should begin at puberty. Early TART lesions often respond to tighter ACTH control through optimized steroid treatment.

Poor outcomes related to genital surgery or surgical complications contribute to morbidity in female patients. Patients with CAH have a higher prevalence of adrenal masses, most commonly myelolipomas, compared to the background population. Uncontrolled ACTH stimulation of the adrenal cortex is the probable cause.

Other than these complications, patients with CAH often experience suboptimal quality of life, including challenges in psychosocial well-being and sexual function, influenced by multiple factors.[37]

Consultations

An interprofessional approach is essential for managing 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Pediatric endocrinologists manage hormonal imbalances and glucocorticoid therapy. Pediatric surgeons may address ambiguous genitalia, whereas gynecologists and fertility specialists manage reproductive health and infertility. Urologists handle TART-related issues, and adult endocrinologists ensure continuity of care. Radiologists assist in diagnostics, and medical geneticists provide genetic counseling. Psychologists support patients with emotional and psychological challenges. Effective consultation with these specialists ensures a holistic, patient-centered approach to managing 21-hydroxylase deficiency.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient and family education on proper treatment, especially compliance with medical therapy, is crucial for patients with CAH. Over- and under-treatment with glucocorticosteroids can have profound effects on the growth and health of these patients. When patients are older, caregivers and patients themselves need to be counseled on proper treatment and when to seek medical care.

Providing advice on preventing life-threatening events, such as adrenal crises, is essential for these individuals.

Genetic counseling should be provided to children transitioning to adult care, at diagnosis to patients with nonclassic CAH, and patients planning for a pregnancy regarding inheritance and chances of recurrence in the next generation.

Pearls and Other Issues

Key points and considerations in managing 21-hydroxylase deficiency are as follows:

- There are 3 main forms of 21-hydroxylase deficiency—classic (virilizing and salt wasting, about 75%), simple virilizing CAH (no salt wasting, about 25%), and nonclassic CAH (mild symptoms, most common)

- Both molecular genetic testing of the fetus and prenatal treatment of mothers with dexamethasone in specific settings are possible interventions.

- Antenatal dexamethasone treatment, if the fetus is 46XX, can prevent virilization but is experimental as of now and should be offered under protocols approved by Institutional Review Boards.[5]

- In patients with ambiguous genitalia, the diagnosis is not difficult; however, in affected males with no symptoms, newborn screening may be lifesaving. Without it, the diagnosis can be missed until the patient is in an acute adrenal crisis.

- CAH treatment aims to prevent adrenal crisis and virilization and achieve normal growth, pubertal development, sexual function, and fertility. Both male and female patients are fertile but have reduced fertility rates. This consequence is due to biological, psychological, social, and sexual factors.

- The prevalence of metabolic abnormalities such as obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and PCOS has been reported to be high due to the disease itself or glucocorticoid treatment.

- Current standard therapy is imperfect, and there is an unmet need to develop newer therapies to reduce complications of supraphysiological steroid doses. Several promising therapies are under development, but the coming future reveals their safety and effectiveness.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

CAH is a relatively rare autosomal recessive disorder associated with significant mental and physical morbidity and mortality. Newborn screening is crucial for detecting all infants with classic CAH, significantly reducing mortality and morbidity rates due to delayed diagnosis. Early referral to specialists and facilities that provide medical and surgical treatment for this condition enhances overall outcomes and improves the quality of life for individuals. Other than medical management by pediatric endocrinologists and surgical management by pediatric urology surgeons, psychologists and social workers play crucial roles in addressing the psychosocial aspects of care. Transition clinics comprising pediatric medical and surgical specialists and adult counterparts may play an important role in trust building and a smooth transition from pediatric to adult care.

Ethical considerations must be considered when determining treatment options and respecting patient autonomy in decision-making. Caregivers of children diagnosed with CAH must be fully educated about treatment options and possible complications of the condition. Responsibilities within the interprofessional team should be clearly defined, with each member contributing their specialized knowledge and skills to optimize patient care. Effective interprofessional communication fosters a collaborative environment where information is shared, questions are encouraged, and concerns are addressed promptly.

Lastly, care coordination is pivotal in ensuring seamless and efficient patient care. Clinicians, advanced practitioners, pharmacists, and other healthcare providers must collaborate to streamline the patient's journey, from diagnosis through treatment and follow-up. This coordination minimizes errors, reduces delays, and enhances patient safety, ultimately leading to improved outcomes and patient-centered care that prioritizes the well-being and satisfaction of individuals affected by 21-hydroxylase deficiency.

Media

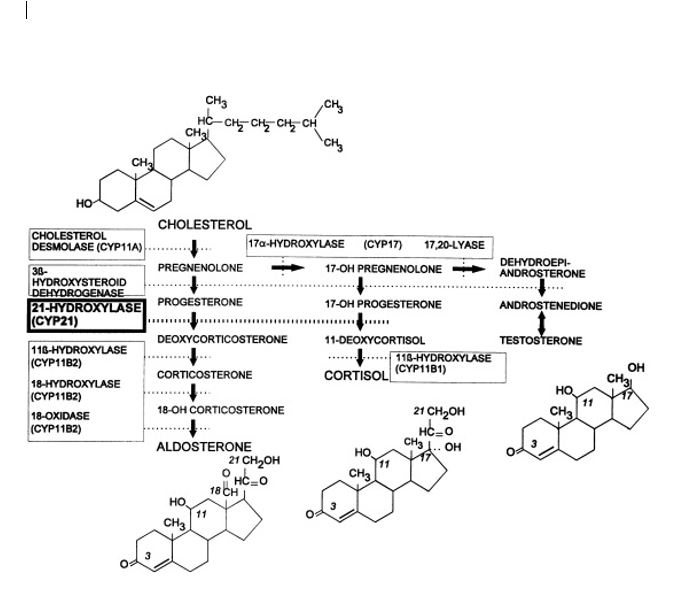

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Synthesis of adrenal cortex hormones. The pathways for synthesis of progesterone and mineralocorticoids (aldosterone), glucocorticoids (cortisol), androgens (testosterone and dihydrotestosterone), and estrogens (estradiol) are arranged from left to right. The enzymatic activities catalyzing each bioconversion are written in boxes. For those activities mediated by specific cytochromes P450, the systematic name of the enzyme (“CYP” followed by a number) is listed in parentheses. CYP11B2 and CYP17 have multiple activities. The planar structures of cholesterol, aldosterone, cortisol, dihydrotestosterone, and estradiol are placed near the corresponding labels

Speiser PW, White PC. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Clin Endocrinol. 1998;49(4):411-417; doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1998.00559.x.

References

Tajima T. Health problems of adolescent and adult patients with 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Clinical pediatric endocrinology : case reports and clinical investigations : official journal of the Japanese Society for Pediatric Endocrinology. 2018:27(4):203-213. doi: 10.1297/cpe.27.203. Epub 2018 Oct 30 [PubMed PMID: 30393437]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMcCann-Crosby B, Placencia FX, Adeyemi-Fowode O, Dietrich J, Franciskovich R, Gunn S, Axelrad M, Tu D, Mann D, Karaviti L, Sutton VR. Challenges in Prenatal Treatment with Dexamethasone. Pediatric endocrinology reviews : PER. 2018 Sep:16(1):186-193. doi: 10.17458/per.vol16.2018.mcpa.dexamethasone. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30371037]

Nasir H, Ali SI, Haque N, Grebe SK, Kirmani S. Compound heterozygosity for a whole gene deletion and p.R124C mutation in CYP21A2 causing nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Annals of pediatric endocrinology & metabolism. 2018 Sep:23(3):158-161. doi: 10.6065/apem.2018.23.3.158. Epub 2018 Sep 28 [PubMed PMID: 30286573]

Merke DP, Auchus RJ. Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia Due to 21-Hydroxylase Deficiency. The New England journal of medicine. 2020 Sep 24:383(13):1248-1261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1909786. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32966723]

Speiser PW, Arlt W, Auchus RJ, Baskin LS, Conway GS, Merke DP, Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, Miller WL, Murad MH, Oberfield SE, White PC. Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia Due to Steroid 21-Hydroxylase Deficiency: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2018 Nov 1:103(11):4043-4088. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-01865. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30272171]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNour MA, Gill H, Mondal P, Inman M, Urmson K. Perioperative care of congenital adrenal hyperplasia - a disparity of physician practices in Canada. International journal of pediatric endocrinology. 2018:2018():8. doi: 10.1186/s13633-018-0063-4. Epub 2018 Sep 10 [PubMed PMID: 30214458]

Dörr HG, Penger T, Albrecht A, Marx M, Völkl TMK. Birth Size in Neonates with Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase Deficiency. Journal of clinical research in pediatric endocrinology. 2019 Feb 20:11(1):41-45. doi: 10.4274/jcrpe.galenos.2018.2018.0149. Epub 2018 Sep 4 [PubMed PMID: 30178749]

Chen S, Wu L, Ma X, Guo L, Zhang J, Gao H, Zhang T. Current status and prospects of congenital adrenal hyperplasia: A bibliometric and visualization study. Medicine. 2024 Nov 8:103(45):e40297. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000040297. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39533614]

ICMR Task Force on Inherited Metabolic Disorders. Newborn Screening for Congenital Hypothyroidism and Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia. Indian journal of pediatrics. 2018 Nov:85(11):935-940. doi: 10.1007/s12098-018-2645-9. Epub 2018 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 29549556]

Daae E, Feragen KB, Nermoen I, Falhammar H. Psychological adjustment, quality of life, and self-perceptions of reproductive health in males with congenital adrenal hyperplasia: a systematic review. Endocrine. 2018 Oct:62(1):3-13. doi: 10.1007/s12020-018-1723-0. Epub 2018 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 30128958]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRama Chandran S, Loh LM. The importance and implications of preconception genetic testing for accurate fetal risk estimation in 21-hydroxylase congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH). Gynecological endocrinology : the official journal of the International Society of Gynecological Endocrinology. 2019 Jan:35(1):28-31. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2018.1490399. Epub 2018 Jul 25 [PubMed PMID: 30044156]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDoleschall M, Török D, Mészáros K, Luczay A, Halász Z, Németh K, Szücs N, Kiss R, Tőke J, Sólyom J, Fekete G, Patócs A, Igaz P, Tóth M. [Steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency, the most frequent cause of congenital adrenal hyperplasia]. Orvosi hetilap. 2018 Feb:159(7):269-277. doi: 10.1556/650.2018.30986. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29429350]

Held PK, Bialk ER, Lasarev MR, Allen DB. 21-Deoxycortisol is a Key Screening Marker for 21-Hydroxylase Deficiency. The Journal of pediatrics. 2022 Mar:242():213-219.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.10.063. Epub 2021 Nov 13 [PubMed PMID: 34780778]

Schröder MAM, Neacşu M, Adriaansen BPH, Sweep FCGJ, Ahmed SF, Ali SR, Bachega TASS, Baronio F, Birkebæk NH, de Bruin C, Bonfig W, Bryce J, Clemente M, Cools M, Elsedfy H, Globa E, Guran T, Güven A, Amr NH, Janus D, Taube NL, Markosyan R, Miranda M, Poyrazoğlu Ş, Rees A, Salerno M, Stancampiano MR, Vieites A, de Vries L, Yavas Abali Z, Span PN, Claahsen-van der Grinten HL. Hormonal control during infancy and testicular adrenal rest tumor development in males with congenital adrenal hyperplasia: a retrospective multicenter cohort study. European journal of endocrinology. 2023 Oct 17:189(4):460-468. doi: 10.1093/ejendo/lvad143. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37837609]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceEngels M, Span PN, van Herwaarden AE, Sweep FCGJ, Stikkelbroeck NMML, Claahsen-van der Grinten HL. Testicular Adrenal Rest Tumors: Current Insights on Prevalence, Characteristics, Origin, and Treatment. Endocrine reviews. 2019 Aug 1:40(4):973-987. doi: 10.1210/er.2018-00258. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30882882]

Teede HJ, Tay CT, Laven JJE, Dokras A, Moran LJ, Piltonen TT, Costello MF, Boivin J, Redman LM, Boyle JA, Norman RJ, Mousa A, Joham AE. Recommendations From the 2023 International Evidence-based Guideline for the Assessment and Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2023 Sep 18:108(10):2447-2469. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgad463. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37580314]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceYanase T, Tajima T, Katabami T, Iwasaki Y, Tanahashi Y, Sugawara A, Hasegawa T, Mune T, Oki Y, Nakagawa Y, Miyamura N, Shimizu C, Otsuki M, Nomura M, Akehi Y, Tanabe M, Kasayama S. Diagnosis and treatment of adrenal insufficiency including adrenal crisis: a Japan Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline [Opinion]. Endocrine journal. 2016 Sep 30:63(9):765-784 [PubMed PMID: 27350721]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMass Screening Committee, Japanese Society for Pediatric Endocrinology, Japanese Society for Mass Screening, Ishii T, Anzo M, Adachi M, Onigata K, Kusuda S, Nagasaki K, Harada S, Horikawa R, Minagawa M, Minamitani K, Mizuno H, Yamakami Y, Fukushi M, Tajima T. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of 21-hydroxylase deficiency (2014 revision). Clinical pediatric endocrinology : case reports and clinical investigations : official journal of the Japanese Society for Pediatric Endocrinology. 2015 Jul:24(3):77-105. doi: 10.1297/cpe.24.77. Epub 2015 Jul 18 [PubMed PMID: 26594092]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMerke DP, Mallappa A, Arlt W, Brac de la Perriere A, Lindén Hirschberg A, Juul A, Newell-Price J, Perry CG, Prete A, Rees DA, Reisch N, Stikkelbroeck N, Touraine P, Maltby K, Treasure FP, Porter J, Ross RJ. Modified-Release Hydrocortisone in Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2021 Apr 23:106(5):e2063-e2077. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab051. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33527139]

Nella AA, Mallappa A, Perritt AF, Gounden V, Kumar P, Sinaii N, Daley LA, Ling A, Liu CY, Soldin SJ, Merke DP. A Phase 2 Study of Continuous Subcutaneous Hydrocortisone Infusion in Adults With Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2016 Dec:101(12):4690-4698 [PubMed PMID: 27680873]

El-Maouche D, Merke DP, Vogiatzi MG, Chang AY, Turcu AF, Joyal EG, Lin VH, Weintraub L, Plaunt MR, Mohideen P, Auchus RJ. A Phase 2, Multicenter Study of Nevanimibe for the Treatment of Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2020 Aug 1:105(8):2771-8. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa381. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32589738]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePrete A, Auchus RJ, Ross RJ. Clinical advances in the pharmacotherapy of congenital adrenal hyperplasia. European journal of endocrinology. 2021 Nov 30:186(1):R1-R14. doi: 10.1530/EJE-21-0794. Epub 2021 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 34735372]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAuchus RJ, Buschur EO, Chang AY, Hammer GD, Ramm C, Madrigal D, Wang G, Gonzalez M, Xu XS, Smit JW, Jiao J, Yu MK. Abiraterone acetate to lower androgens in women with classic 21-hydroxylase deficiency. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2014 Aug:99(8):2763-70. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1258. Epub 2014 Apr 29 [PubMed PMID: 24780050]

Auchus RJ, Hamidi O, Pivonello R, Bancos I, Russo G, Witchel SF, Isidori AM, Rodien P, Srirangalingam U, Kiefer FW, Falhammar H, Merke DP, Reisch N, Sarafoglou K, Cutler GB Jr, Sturgeon J, Roberts E, Lin VH, Chan JL, Farber RH, CAHtalyst Adult Trial Investigators. Phase 3 Trial of Crinecerfont in Adult Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia. The New England journal of medicine. 2024 Aug 8:391(6):504-514. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2404656. Epub 2024 Jun 1 [PubMed PMID: 38828955]

Sarafoglou K, Kim MS, Lodish M, Felner EI, Martinerie L, Nokoff NJ, Clemente M, Fechner PY, Vogiatzi MG, Speiser PW, Auchus RJ, Rosales GBG, Roberts E, Jeha GS, Farber RH, Chan JL, CAHtalyst Pediatric Trial Investigators. Phase 3 Trial of Crinecerfont in Pediatric Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia. The New England journal of medicine. 2024 Aug 8:391(6):493-503. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2404655. Epub 2024 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 38828945]

Auchus RJ, Sarafoglou K, Fechner PY, Vogiatzi MG, Imel EA, Davis SM, Giri N, Sturgeon J, Roberts E, Chan JL, Farber RH. Crinecerfont Lowers Elevated Hormone Markers in Adults With 21-Hydroxylase Deficiency Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2022 Feb 17:107(3):801-812. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab749. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34653252]

Erginel B, Ozdemir B, Karadeniz M, Poyrazoglu S, Keskin E, Soysal FG. Long-term 10-year comparison of girls with congenital adrenal hyperplasia who underwent early and late feminizing genitoplasty. Pediatric surgery international. 2023 Jun 29:39(1):222. doi: 10.1007/s00383-023-05498-8. Epub 2023 Jun 29 [PubMed PMID: 37386261]

Almasri J, Zaiem F, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, Tamhane SU, Iqbal AM, Prokop LJ, Speiser PW, Baskin LS, Bancos I, Murad MH. Genital Reconstructive Surgery in Females With Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2018 Nov 1:103(11):4089-4096. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-01863. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30272250]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKrege S, Falhammar H, Lax H, Roehle R, Claahsen-van der Grinten H, Kortmann B, Duranteau L, Nordenskjöld A, dsd-LIFE group. Long-Term Results of Surgical Treatment and Patient-Reported Outcomes in Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia-A Multicenter European Registry Study. Journal of clinical medicine. 2022 Aug 8:11(15):. doi: 10.3390/jcm11154629. Epub 2022 Aug 8 [PubMed PMID: 35956243]

Falhammar H, Holmdahl G, Nyström HF, Nordenström A, Hagenfeldt K, Nordenskjöld A. Women's response regarding timing of genital surgery in congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Endocrine. 2025 Feb:87(2):830-835. doi: 10.1007/s12020-024-04080-z. Epub 2024 Oct 18 [PubMed PMID: 39422838]

Lee PA, Fuqua JS, Houk CP, Kogan BA, Mazur T, Caldamone A. Individualized care for patients with intersex (disorders/differences of sex development): part I. Journal of pediatric urology. 2020 Apr:16(2):230-237. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2020.02.013. Epub 2020 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 32249189]

Pofi R, Ji X, Krone NP, Tomlinson JW. Long-term health consequences of congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Clinical endocrinology. 2024 Oct:101(4):318-331. doi: 10.1111/cen.14967. Epub 2023 Sep 7 [PubMed PMID: 37680029]

Bachelot A, Grouthier V, Courtillot C, Dulon J, Touraine P. MANAGEMENT OF ENDOCRINE DISEASE: Congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency: update on the management of adult patients and prenatal treatment. European journal of endocrinology. 2017 Apr:176(4):R167-R181. doi: 10.1530/EJE-16-0888. Epub 2017 Jan 23 [PubMed PMID: 28115464]

Khattab A, Yau M, Qamar A, Gangishetti P, Barhen A, Al-Malki S, Mistry H, Anthony W, Toralles MB, New MI. Long term outcomes in 46, XX adult patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia reared as males. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 2017 Jan:165(Pt A):12-17. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2016.03.033. Epub 2016 Apr 25 [PubMed PMID: 27125449]

King TF, Lee MC, Williamson EE, Conway GS. Experience in optimizing fertility outcomes in men with congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21 hydroxylase deficiency. Clinical endocrinology. 2016 Jun:84(6):830-6. doi: 10.1111/cen.13001. Epub 2016 Feb 15 [PubMed PMID: 26666213]

Wiromrat P, Raruenrom Y, Namphaisan P, Wongsurawat N, Panamonta O, Pongchaiyakul C. Prednisolone impairs trabecular bone score changes in adolescents with 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Clinical and experimental pediatrics. 2024 Nov 13:():. doi: 10.3345/cep.2024.01060. Epub 2024 Nov 13 [PubMed PMID: 39533718]

Lind-Holst M, Hansen D, Main KM, Juul A, Andersen MS, Dunø M, Rasmussen ÅK, Jørgensen N, Gravholt CH, Berglund A. Delineating the psychiatric morbidity spectrum in congenital adrenal hyperplasia: a population-based registry study. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2024 Nov 15:():. pii: dgae780. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgae780. Epub 2024 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 39545512]

Rangaswamaiah S, Gangathimmaiah V, Nordenstrom A, Falhammar H. Bone Mineral Density in Adults With Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2020:11():493. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.00493. Epub 2020 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 32903805]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFalhammar H, Frisén L, Hirschberg AL, Nordenskjöld A, Almqvist C, Nordenström A. Increased Prevalence of Fractures in Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia: A Swedish Population-based National Cohort Study. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2022 Jan 18:107(2):e475-e486. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab712. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34601607]

Tamhane S, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, Iqbal AM, Prokop LJ, Bancos I, Speiser PW, Murad MH. Cardiovascular and Metabolic Outcomes in Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2018 Nov 1:103(11):4097-4103. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-01862. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30272185]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKim JH, Choi S, Lee YA, Lee J, Kim SG. Epidemiology and Long-Term Adverse Outcomes in Korean Patients with Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia: A Nationwide Study. Endocrinology and metabolism (Seoul, Korea). 2022 Feb:37(1):138-147. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2021.1328. Epub 2022 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 35255606]