Introduction

Gallbladder carcinoma is a rare malignancy but represents almost 50% of all biliary tract cancer.[1] Most tumors are adenocarcinomas, with squamous, adenosquamous, and neuroendocrine tumors being less common. Gallbladder neoplasms are more prevalent in women, with marked geographic variation in incidence. Most gallbladder tumors arise from the mucosal lining as the gallbladder lacks a submucosal layer and subsequently spread through the thin muscularis early in the disease course. Early symptoms may be similar to biliary colic or cholecystitis and might account for the late stage of diagnosis associated with this cancer. Consequently, tumors are often nonresectable at diagnosis.

Surgical resection is the treatment of choice, and not infrequently, a focus of early-stage carcinoma may be incidentally detected in patients undergoing cholecystectomy. In contrast to other biliary carcinomas, gallbladder carcinoma is associated with a higher rate of distant metastatic disease and may derive more benefit from chemotherapy. Chemotherapy is used in the adjuvant setting and palliative care.[2] The overall prognosis is poor, with 5-year survival rates of <20%. Recent advances in studying the genetic drivers and molecular profile of these tumors have heralded the use of targeted agents, hopefully improving the prognosis of this disease.[3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Gallbladder Carcinoma Risk Factors

Chronic gallbladder inflammation is the most common pathogenic pathway associated with gallbladder carcinoma.[4] This chronic inflammation underlies many of the following risk factors for the development of this neoplasm.

- Cholelithiasis: The strongest correlation to developing gallbladder cancer is cholelithiasis. Gallstones cause a 4- to 5-fold increase in the prevalence of cancer. The risk increases with increases with gallstone size and chronicity of inflammation. Stones greater than 3 cm in size are most strongly associated with cancer, especially when symptomatic.[5]

- Gallbladder calcification: Also known as porcelain gallbladder (see Image. Porcelain Gallbladder), this is a condition where the inner gallbladder wall is encrusted with calcium. Porcelain gallbladder is very rare and was previously believed to be associated with gallbladder malignancies. However, the current opinion is that the risk of malignancy is small.[6]

- Gallbladder polyps: Approximately 4% to 7% of the population may develop gallbladder polyps, the incidence of which increases with age. True adenomatous gallbladder polyps are considered neoplastic, unlike inflammatory polyps and pseudopolyps. Adenomatous gallbladder polyps are rare and often associated with gallstones. The malignant potential increases with polyps measuring greater than 1 cm; malignant polyps tend to be solitary and larger than 2 cm in diameter.[6][7][8]

- Congenital biliary cysts and abnormal pancreaticobiliary anatomy [8]

- Areas with endemic Salmonella Typhi and Helicobacter pylori infection [8]

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis and inflammatory bowel disease [8]

- Extrinsic carcinogens, including medications (eg, methyldopa, isoniazid), work exposure (eg, methylcellulose, radon), and lifestyle (eg, cigarette smoking, obesity, high carbohydrate intake) [8]

Epidemiology

Gallbladder adenocarcinoma is the most common biliary tumor, although overall a relatively rare cancer. More than 50% of cases are detected incidentally at the time of cholecystectomy.[9] In 2023, roughly 5000 new cases of gallbladder cancer were diagnosed, with a 5-year overall survival rate of 19%. The incidence of gallbladder carcinoma increases with age and is reported to be more common in women. Worldwide, the incidence of gallbladder cancer is high in specific populations due to the high prevalence of gallstones and chronic gallbladder infections; according to the 2018 GLOBOCAN data, Bolivia, Chile, and parts of the Indian subcontinent have the highest rates.[10]

Pathophysiology

Chronic inflammation is the primary oncogenic driver of gallbladder carcinoma. Toxins and direct injury may be additional pathophysiologic factors. The mutational profile of gallbladder adenocarcinoma most commonly involves K-ras, TP53, CDKN2a, and c-erb-b2 mutations. In addition, gene promoter hypermethylation has been increasingly identified as a pathogenic contributor. In a subset of patients, advancement to cancer may follow a pathway similar to cancer that arises from premalignant lesions in other organs, such as colon cancer (ie, gallbladder adenomas), which progresses from dysplasia to invasive cancers.[11] The heterogeneity in genetic drivers is further evidence of the complex pathogenesis of gallbladder carcinoma.[12]

Histopathology

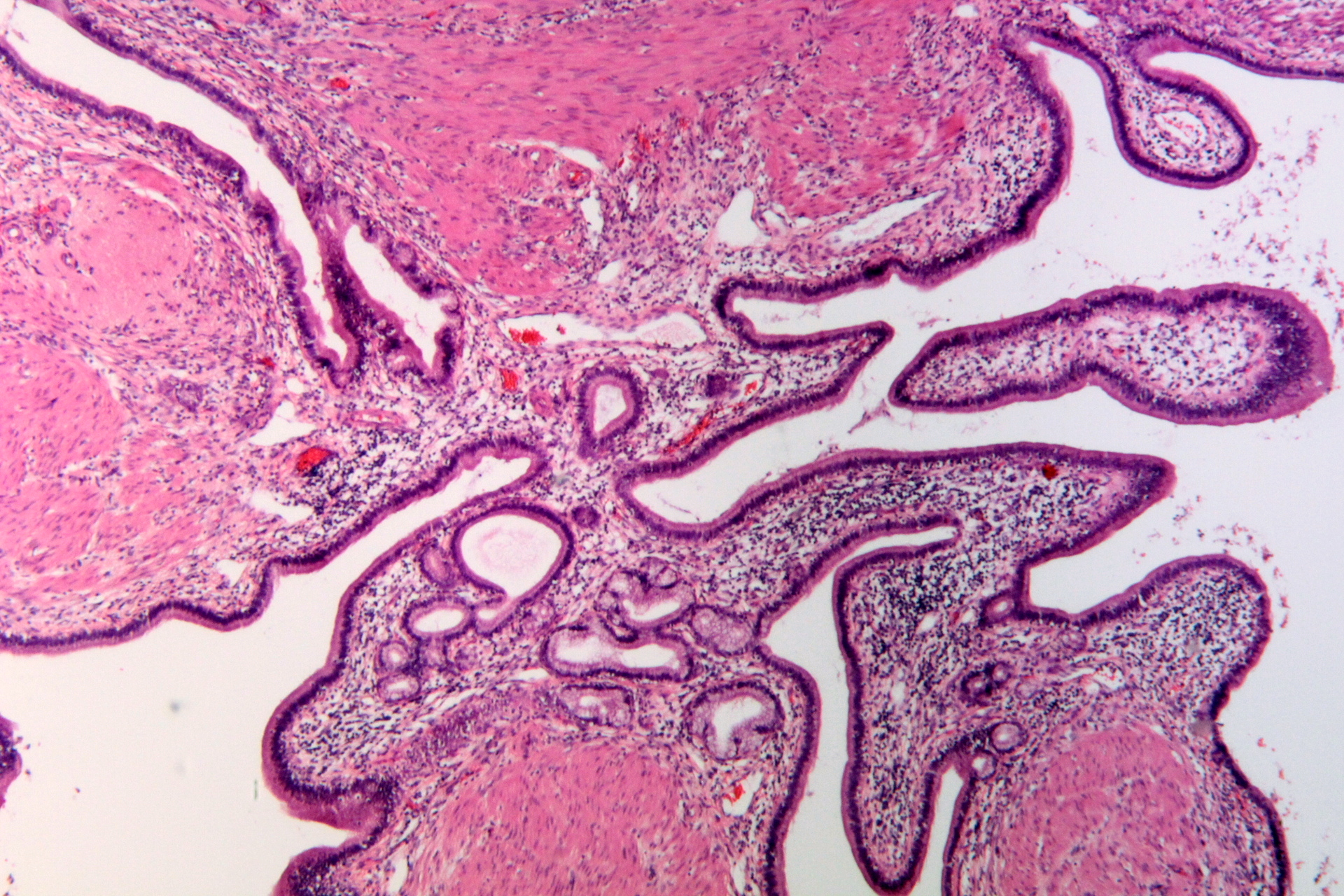

Gallbladder adenocarcinomas are often associated with cholelithiasis or gallbladder polyps on gross examination. Direct extension through the serosa into the liver or onto the peritoneal surface may be present. The tumor may be polyploid or infiltrative, often with the adjacent gallbladder wall thickening. Chronic cholecystitis is common. When diagnosed incidentally on cholecystectomy specimens, the malignant lesions may be subtle and require careful examination to make a diagnosis.[13]

Microscopically, most tumors are adenocarcinomas, with cuboidal or columnar epithelial gland formation varying by the degree of tumor differentiation (see Image. Gallbladder Adenomyomatosis). Desmoplasia is a common feature. Variants include the intestinal type, which resembles colon adenocarcinoma; the mucinous type, which has over 50% extracellular mucin; and other rarer subtypes.[14]

History and Physical

Early-stage gallbladder carcinoma is often found incidentally during surgery, as it is typically asymptomatic. When symptoms do occur, they are frequently nonspecific and similar to those of other gallbladder conditions. Patients with larger lesions may experience symptoms such as biliary colic or cholecystitis. Since many gallbladder tumors are found alongside cholelithiasis and cholecystitis, it can be difficult to distinguish between the symptoms of these conditions. Advanced stages of gallbladder cancer can cause vague symptoms such as abdominal pain, nausea, weakness, anorexia, loss of appetite, weight loss, and jaundice. More severe cases may lead to biliary obstruction or fistulization to the biliary tree or the duodenum, which are signs of advanced disease.

The physical examination of a patient with gallbladder carcinoma may reveal tenderness in the right upper quadrant, a positive Murphy sign, jaundice, or a Courvoisier sign (a nontender, palpable gallbladder with jaundice) may be present. Hepatomegaly, a palpable abdominal mass, ascites, and bowel obstruction are signs that indicate metastatic disease.[15]

Evaluation

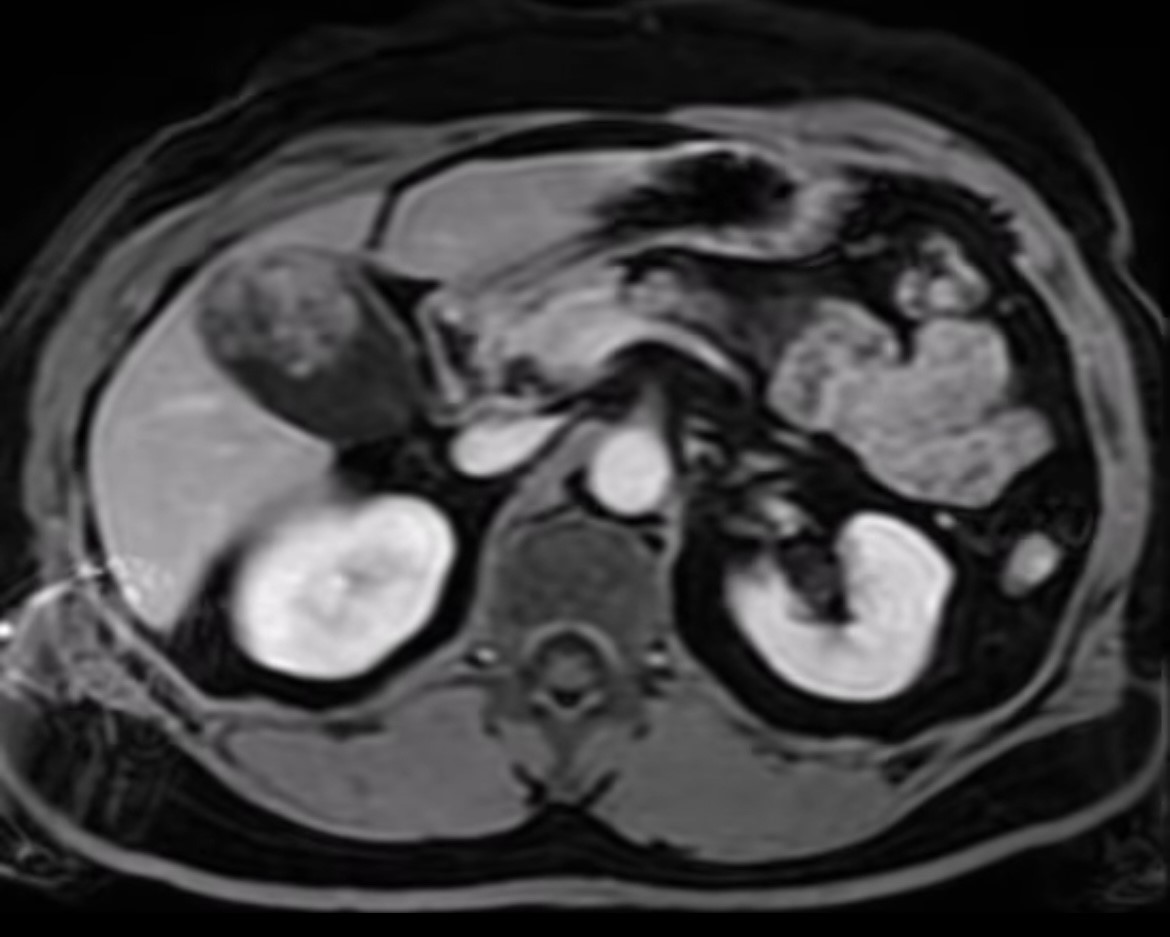

When gallbladder carcinoma is suspected, patients should undergo laboratory evaluations, including a complete blood count, basic chemistry panel, and liver function tests. A right upper quadrant ultrasound is usually the first step in evaluating biliary pathology and may demonstrate gallbladder tumors, polyps, cholelithiasis, cholecystitis, or biliary obstruction (see Image. Gallbladder Stone). Further imaging with computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), or positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) scans may be indicated if the suspicion for gallbladder carcinoma is high.

CT provides excellent anatomic detail and can identify local invasion, lymphadenopathy, and metastatic disease (see Image. Gallbladder Carcinoma). MRI can help assess disease extent more accurately and identify unresectable tumors with hepatoduodenal ligament invasion, vasculature encasement, and lymph node involvement.[16] Both modalities are insensitive in discriminating benign from malignant lymph nodes <10 mm in size. EUS is more accurate than ultrasound, CT, and MRI, especially in detecting lymphadenopathy. EUS also allows suspicious lymph nodes to be sampled. Most gallbladder cancers are 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose avid by PET/CT, and PET/CT can help identify occult metastatic disease.

Tumor markers, such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9), are frequently elevated but considered nondiagnostic due to lack of specificity (CA 19-9 92.7% versus CEA 79.2%) and sensitivity (CA 19-9 50% versus CEA 79.4%). Baseline CEA and CA 19-9 tests are useful for monitoring response to therapy.[17] In patients with suspected locally advanced disease but without any evidence of distant metastatic disease, a diagnostic laparoscopy may be indicated to help inform systemic therapy.

Treatment / Management

The only definitive treatment for gallbladder carcinoma is surgery. Chemotherapy and radiation therapy are used as adjuncts after surgery or in patients with unresectable or advanced metastatic tumors.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses that should also be considered when evaluating gallbladder carcinoma, include:

- Acalculous cholecystitis

- Ampullary carcinoma

- Bile duct strictures

- Bile duct tumors

- Biliary colic

- Biliary disease

- Biliary obstruction

- Cholangitis

- Cholecystitis

Surgical Oncology

Surgical treatment of gallbladder carcinoma depends on the tumor stage and requires complete surgical excision with negative margins. Staging laparoscopy is recommended in patients with bulky tumors; this evaluation may identify radiologically occult metastatic disease.[18][19] Laparoscopy may also be considered when a gallbladder carcinoma is identified incidentally and the pathologic stage is greater than T1a. While historically, excision of the laparoscopic port sites was recommended in patients undergoing reoperation for gallbladder carcinoma after initial laparoscopic cholecystectomy, this is no longer recommended.[20] The following surgical procedures are recommended based on gallbladder carcinoma staging:

- T1a tumors: Tumors confined to the mucosa require only a cholecystectomy. This typically occurs when a gallbladder carcinoma is incidentally detected during pathologic examination.

- T1b, T2, and T3 tumors: Patients with more advanced disease should undergo a radical cholecystectomy and portal lymphadenectomy.

- A radical cholecystectomy typically involves the en-bloc resection of the gallbladder with a limited resection of the adjacent segments 4b and 5. Typically, patients who have tumor invasion into the liver need more extensive liver resections to obtain negative margins. However, resections beyond segments 4b and 5 are typically not indicated and should be performed only in the appropriate clinical situations where negative margins are likely to impact survival. For example, extended hepatic resection in cases with bulky lymphadenopathy is unlikely to be beneficial. Routine extended hepatic and biliary resections increase morbidity and mortality without any survival benefit. Bile duct excision and biliary reconstruction may be indicated if the cystic duct margins are persistently positive or if lymph nodes along the extrahepatic bile duct are adherent.

- Portal lymphadenectomy involves removing all the lymph nodes along the hepatoduodenal ligament, the porta hepatis, and the retroduodenal region. Enlarged lymph nodes beyond these areas should be considered metastatic.

Radiation Oncology

Adjuvant Therapy

Radiotherapy (RT) may be used in the adjuvant setting for gallbladder carcinoma.[21] In patients who undergo a complete resection with microscopically negative margins, RT is not indicated. However, in patients with a microscopically positive or grossly positive surgical margin, chemoradiotherapy is generally used to reduce local recurrence. The radiation dose depends on the tumor location, the tolerance of surrounding organs, and underlying liver function. Image-guided techniques, such as 3-dimensional conformal and intensity-modulated RT, improve targeting and reduce toxicity. The radiation field should include the operative bed and the regional lymph nodes (eg, portal, celiac, para-aortic, superior mesenteric artery). Typical doses range from 40 to 45 Gy to the lymph nodes and 55 to 60 Gy to the tumor site.[22] Studies have not determined the survival benefit of RT. Patients with node-positive disease may also receive RT. External beam RT with a chemo-sensitizing agent such as capecitabine or gemcitabine is typically used.[23]

Unresectable Disease

RT may be used in unresectable disease to provide local control and symptom relief.[21] Both external beam RT and stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) may be employed. SBRT allows very high doses of radiation to target lesions with a high degree of accuracy and provides local control rates that appear to be better than conventional fractionated external beam RT. RT is almost always administered with concurrent radiosensitizing chemotherapy. Typical doses in this setting are higher than those in adjuvant therapy.

Medical Oncology

Adjuvant Therapy

Postoperative therapy should be offered within 8 to 12 weeks and requires baseline laboratory tests and imaging before therapy initiation. Adjuvant treatment may be delayed in cases where there are significant surgical complications or because of other patient-related factors that may impair chemotherapy tolerance. In general, the efficacy of adjuvant therapy decreases as the time to initiation increases. After resection, adjuvant therapy should be offered to patients with positive surgical margins, positive lymph nodes, or vascular involvement. The role of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with completely resected specimens with microscopically negative margins is unclear. The benefit of adjuvant therapy is based on 2 trials, including the BILCAP trial and a randomized trial from Japan, which used single-agent adjuvant treatment. In the BILCAP trial, adjuvant capecitabine improved overall survival without chemotherapy, although this trend was not statistically significant.[24] Adjuvant treatment is currently accepted as a standard of care after resection. However, 2 trials have reported no benefit to gemcitabine-based regimens, which are presently discouraged. Most trials of systemic therapy combine gallbladder carcinoma with all biliary tract cancers. As gallbladder carcinoma has a higher rate of distant metastatic disease than other biliary tract cancers, chemotherapy may likely have additional benefits in these patients.[25][26][25]

Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is currently used in borderline resectable tumors and is a 2B recommendation in NCCN guidelines. Some patients may have an adequate response that allows for subsequent resection. For patients with upfront resectable disease, the routine use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy is not supported by evidence.[27]

Locally Advanced or Metastatic Disease

Chemotherapy can significantly extend survival in patients with metastatic disease. More recently, immunotherapy has improved this benefit. Based on the recent Topaz-1 trial, the combination of durvalumab with gemcitabine and cisplatin was superior to gemcitabine and cisplatin alone.[28] Pembrolizumab, in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin, has also been shown to be superior to chemotherapy alone. In general, these are considered the standard of care.[29] Chemotherapy alone remains the standard of care in several settings where immunotherapy may not be available. Multiple second- and third-line regimens exist for patients with poor performance status, persistent hyperbilirubinemia, or other considerations. With the identification of an increased number of specific tumor mutations and the availability of targeted agents, several targeted agents are now available based on the tumor mutational profile of these cancers.[30]

Staging

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guideline, based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer, 8th edition, provides the following tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM) classification for gallbladder carcinoma:

- T (primary tumor)

- TX: Primary tumor cannot be assessed

- T0: No evidence of primary tumor

- Tis: Carcinoma in situ

- T1: Tumor invades lamina propria or muscular layer

- T1a: Tumor invades lamina propria

- T1b: Tumor invades muscle layer

- T2: Tumor invades the perimuscular connective tissue on the peritoneal side, without the involvement of the serosa (visceral peritoneum) OR tumor invades the perimuscular connective tissue on the hepatic side, with no extension into the liver

- T2a: Tumor invades the perimuscular connective tissue on the peritoneal side, without the involvement of the serosa (visceral peritoneum)

- T2b: Tumor invades the perimuscular connective tissue on the hepatic side, with no extension into the liver

- T3: Tumor perforates the serosa (visceral peritoneum) and/or directly invades the liver and/or 1 other adjacent organ or structure, such as the stomach, duodenum, colon, pancreas, omentum, or extrahepatic bile ducts

- T4: Tumor invades main portal vein or hepatic artery or invades 2 or more extrahepatic organs or structures

- N (regional lymph nodes)

- NX: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed

- N0: No regional lymph node metastasis

- N1: Metastases to 1 to 3 regional lymph nodes

- N2: Metastases to ≥4 or more regional lymph nodes

- M (distant metastasis)

- M0: No distant metastasis

- M1: Distant metastasis [3]

American Joint Committee on Cancer Prognostic Groups

The following gallbladder carcinoma stages can be determined based on the TMN parameters:

- Stage 0: Tis; N0; M0

- Stage I: T1; N0; M0

- Stage II

- IIA: T2a; N0; M0

- IIB: T2b; N0; M0

- Stage III

- IIIA: T3; N0; M0

- IIIB: T1 to T3; N1; M0

- Stage IV

- IVA: T4; N0 to N1; M0

- IVB: Any T; N2; and M0 or any T; any N; and M1 [3]

Prognosis

The prognosis for gallbladder cancer is generally poor, with a 5-year overall survival of less than 20%. Unfortunately, most cases are diagnosed when unresectable. According to the American Cancer Society statistics, the 5-year survival for localized disease is 69%, for regional metastatic disease is 28%, and for distant metastatic disease, 3%.[3] T1a tumors that are entirely resected have a nearly 100% 5-year survival.

Complications

Complications from gallbladder carcinoma can be related to the disease itself or due to therapeutic interventions. Please see StatPearls' companion resources, "Cancer Chemotherapy" and "Adverse Effects of Radiation Therapy," for more information on therapeutic complications.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Gallbladder carcinoma is a rare but aggressive cancer that often has a delayed presentation due to its silent progression. Patients with large gallstones or polyps, chronic cholecystitis, or other high-risk lesions should seek medical evaluation. Treatment involves surgery, chemotherapy, and sometimes radiation. After surgery, adjuvant therapy aims to prevent recurrence. Regular follow-up appointments and imaging scans are crucial to monitor for any signs of recurrence. Clinical trials may offer additional treatment options. Support from an interprofessional team and access to resources for psychosocial needs are essential for coping with the challenges of this diagnosis. Early detection and comprehensive care strategies can improve outcomes and quality of life for patients with gallbladder adenocarcinoma.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Healthcare professionals must possess clinical expertise to diagnose and treat gallbladder adenocarcinoma accurately. Strategic planning ensures timely interventions and optimal patient outcomes. Responsibilities include delivering compassionate care, advocating for patients, and promoting safety. Interprofessional communication fosters collaboration among physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and others, enhancing care coordination and patient-centeredness. As a cancer that has a poor prognosis, enrolling patients in clinical trials and providing them with pathways to accessing the most advanced available care will help advance the field and improve survival. By synergizing skills, strategy, ethics, responsibilities, communication, and coordination, healthcare teams can optimize patient care, safety, and outcomes in the challenging landscape of gallbladder adenocarcinoma management.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Gallbladder Adenomyomatosis. Gallbladder adenomyomatosis on a background of chronic cholecystitis. Note the multiple Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses mixed with smooth muscle fibers.

Patho, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2017 Jan:67(1):7-30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. Epub 2017 Jan 5 [PubMed PMID: 28055103]

Goetze TO. Gallbladder carcinoma: Prognostic factors and therapeutic options. World journal of gastroenterology. 2015 Nov 21:21(43):12211-7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i43.12211. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26604631]

Benson AB, D'Angelica MI, Abrams T, Abbott DE, Ahmed A, Anaya DA, Anders R, Are C, Bachini M, Binder D, Borad M, Bowlus C, Brown D, Burgoyne A, Castellanos J, Chahal P, Cloyd J, Covey AM, Glazer ES, Hawkins WG, Iyer R, Jacob R, Jennings L, Kelley RK, Kim R, Levine M, Palta M, Park JO, Raman S, Reddy S, Ronnekleiv-Kelly S, Sahai V, Singh G, Stein S, Turk A, Vauthey JN, Venook AP, Yopp A, McMillian N, Schonfeld R, Hochstetler C. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Biliary Tract Cancers, Version 2.2023. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2023 Jul:21(7):694-704. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2023.0035. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37433432]

Roa I, Araya JC, Villaseca M, De Aretxabala X, Riedemann P, Endoh K, Roa J. Preneoplastic lesions and gallbladder cancer: an estimate of the period required for progression. Gastroenterology. 1996 Jul:111(1):232-6 [PubMed PMID: 8698204]

Alshahri TM, Abounozha S. Best evidence topic: Does the presence of a large gallstone carry a higher risk of gallbladder cancer? Annals of medicine and surgery (2012). 2021 Jan:61():93-96. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2020.12.023. Epub 2020 Dec 28 [PubMed PMID: 33425346]

Liu K, Katelaris P. Education and imaging. Gastrointestinal: Porcelain gallbladder. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2015 Apr:30(4):648. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12860. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25776955]

Sarici IS, Duzgun O. Gallbladder polypoid lesions }15mm as indicators of T1b gallbladder cancer risk. Arab journal of gastroenterology : the official publication of the Pan-Arab Association of Gastroenterology. 2017 Sep:18(3):156-158. doi: 10.1016/j.ajg.2017.09.003. Epub 2017 Sep 27 [PubMed PMID: 28958638]

Wu T, Sun Z, Jiang Y, Yu J, Chang C, Dong X, Yan S. Strategy for discriminating cholesterol and premalignancy in polypoid lesions of the gallbladder: a single-centre, retrospective cohort study. ANZ journal of surgery. 2019 Apr:89(4):388-392. doi: 10.1111/ans.14961. Epub 2018 Nov 29 [PubMed PMID: 30497105]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAkki AS, Zhang W, Tanaka KE, Chung SM, Liu Q, Panarelli NC. Systematic Selective Sampling of Cholecystectomy Specimens Is Adequate to Detect Incidental Gallbladder Adenocarcinoma. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2019 Dec:43(12):1668-1673. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001351. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31464710]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSu J, Liang Y, He X. Global, regional, and national burden and trends analysis of gallbladder and biliary tract cancer from 1990 to 2019 and predictions to 2030: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Frontiers in medicine. 2024:11():1384314. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1384314. Epub 2024 Apr 4 [PubMed PMID: 38638933]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSharma A, Sharma KL, Gupta A, Yadav A, Kumar A. Gallbladder cancer epidemiology, pathogenesis and molecular genetics: Recent update. World journal of gastroenterology. 2017 Jun 14:23(22):3978-3998. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i22.3978. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28652652]

Giraldo NA, Drill E, Satravada BA, Dika IE, Brannon AR, Dermawan J, Mohanty A, Ozcan K, Chakravarty D, Benayed R, Vakiani E, Abou-Alfa GK, Kundra R, Schultz N, Li BT, Berger MF, Harding JJ, Ladanyi M, O'Reilly EM, Jarnagin W, Vanderbilt C, Basturk O, Arcila ME. Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Gallbladder Carcinoma and Potential Targets for Intervention. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2022 Dec 15:28(24):5359-5367. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-1954. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36228155]

Roa JC, Basturk O, Adsay V. Dysplasia and carcinoma of the gallbladder: pathological evaluation, sampling, differential diagnosis and clinical implications. Histopathology. 2021 Jul:79(1):2-19. doi: 10.1111/his.14360. Epub 2021 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 33629395]

Bosch DE, Yeh MM, Schmidt RA, Swanson PE, Truong CD. Gallbladder carcinoma and epithelial dysplasia: Appropriate sampling for histopathology. Annals of diagnostic pathology. 2018 Dec:37():7-11. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2018.08.003. Epub 2018 Sep 5 [PubMed PMID: 30216818]

Prasad TL, Kumar A, Sikora SS, Saxena R, Kapoor VK. Mirizzi syndrome and gallbladder cancer. Journal of hepato-biliary-pancreatic surgery. 2006:13(4):323-6 [PubMed PMID: 16858544]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFurlan A, Ferris JV, Hosseinzadeh K, Borhani AA. Gallbladder carcinoma update: multimodality imaging evaluation, staging, and treatment options. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2008 Nov:191(5):1440-7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3599. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18941083]

Strom BL, Maislin G, West SL, Atkinson B, Herlyn M, Saul S, Rodriguez-Martinez HA, Rios-Dalenz J, Iliopoulos D, Soloway RD. Serum CEA and CA 19-9: potential future diagnostic or screening tests for gallbladder cancer? International journal of cancer. 1990 May 15:45(5):821-4 [PubMed PMID: 2335386]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAgarwal AK, Kalayarasan R, Javed A, Gupta N, Nag HH. The role of staging laparoscopy in primary gall bladder cancer--an analysis of 409 patients: a prospective study to evaluate the role of staging laparoscopy in the management of gallbladder cancer. Annals of surgery. 2013 Aug:258(2):318-23. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318271497e. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23059504]

Butte JM, Gönen M, Allen PJ, D'Angelica MI, Kingham TP, Fong Y, Dematteo RP, Blumgart L, Jarnagin WR. The role of laparoscopic staging in patients with incidental gallbladder cancer. HPB : the official journal of the International Hepato Pancreato Biliary Association. 2011 Jul:13(7):463-72. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00325.x. Epub 2011 Jun 7 [PubMed PMID: 21689230]

Fuks D, Regimbeau JM, Pessaux P, Bachellier P, Raventos A, Mantion G, Gigot JF, Chiche L, Pascal G, Azoulay D, Laurent A, Letoublon C, Boleslawski E, Rivoire M, Mabrut JY, Adham M, Le Treut YP, Delpero JR, Navarro F, Ayav A, Boudjema K, Nuzzo G, Scotte M, Farges O. Is port-site resection necessary in the surgical management of gallbladder cancer? Journal of visceral surgery. 2013 Sep:150(4):277-84. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2013.03.006. Epub 2013 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 23665059]

Apisarnthanarax S, Barry A, Cao M, Czito B, DeMatteo R, Drinane M, Hallemeier CL, Koay EJ, Lasley F, Meyer J, Owen D, Pursley J, Schaub SK, Smith G, Venepalli NK, Zibari G, Cardenes H. External Beam Radiation Therapy for Primary Liver Cancers: An ASTRO Clinical Practice Guideline. Practical radiation oncology. 2022 Jan-Feb:12(1):28-51. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2021.09.004. Epub 2021 Oct 21 [PubMed PMID: 34688956]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBen-Josef E, Guthrie KA, El-Khoueiry AB, Corless CL, Zalupski MM, Lowy AM, Thomas CR Jr, Alberts SR, Dawson LA, Micetich KC, Thomas MB, Siegel AB, Blanke CD. SWOG S0809: A Phase II Intergroup Trial of Adjuvant Capecitabine and Gemcitabine Followed by Radiotherapy and Concurrent Capecitabine in Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma and Gallbladder Carcinoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2015 Aug 20:33(24):2617-22. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.2219. Epub 2015 May 11 [PubMed PMID: 25964250]

Ilyas SI, Khan SA, Hallemeier CL, Kelley RK, Gores GJ. Cholangiocarcinoma - evolving concepts and therapeutic strategies. Nature reviews. Clinical oncology. 2018 Feb:15(2):95-111. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.157. Epub 2017 Oct 10 [PubMed PMID: 28994423]

Primrose JN, Fox RP, Palmer DH, Malik HZ, Prasad R, Mirza D, Anthony A, Corrie P, Falk S, Finch-Jones M, Wasan H, Ross P, Wall L, Wadsley J, Evans JTR, Stocken D, Praseedom R, Ma YT, Davidson B, Neoptolemos JP, Iveson T, Raftery J, Zhu S, Cunningham D, Garden OJ, Stubbs C, Valle JW, Bridgewater J, BILCAP study group. Capecitabine compared with observation in resected biliary tract cancer (BILCAP): a randomised, controlled, multicentre, phase 3 study. The Lancet. Oncology. 2019 May:20(5):663-673. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30915-X. Epub 2019 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 30922733]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRizzo A, Brandi G. BILCAP trial and adjuvant capecitabine in resectable biliary tract cancer: reflections on a standard of care. Expert review of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2021 May:15(5):483-485. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2021.1864325. Epub 2020 Dec 18 [PubMed PMID: 33307876]

Lamarca A, Edeline J, McNamara MG, Hubner RA, Nagino M, Bridgewater J, Primrose J, Valle JW. Current standards and future perspectives in adjuvant treatment for biliary tract cancers. Cancer treatment reviews. 2020 Mar:84():101936. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2019.101936. Epub 2019 Dec 4 [PubMed PMID: 31986437]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRizzo A, Brandi G. Neoadjuvant therapy for cholangiocarcinoma: A comprehensive literature review. Cancer treatment and research communications. 2021:27():100354. doi: 10.1016/j.ctarc.2021.100354. Epub 2021 Mar 16 [PubMed PMID: 33756174]

Ebia MI, Sankar K, Osipov A, Hendifar AE, Gong J. TOPAZ-1: a new standard of care for advanced biliary tract cancers? Immunotherapy. 2023 May:15(7):473-476. doi: 10.2217/imt-2022-0269. Epub 2023 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 36950948]

Almhanna K. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in combination with chemotherapy for patients with biliary tract cancer: what did we learn from TOPAZ-1 and KEYNOTE-966. Translational cancer research. 2024 Jan 31:13(1):22-24. doi: 10.21037/tcr-23-1763. Epub 2024 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 38410206]

Kelley RK, Bridgewater J, Gores GJ, Zhu AX. Systemic therapies for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Journal of hepatology. 2020 Feb:72(2):353-363. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.10.009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31954497]