Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Gastrocnemius Muscle

Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Gastrocnemius Muscle

Introduction

The gastrocnemius muscle is a complex muscle that is fundamentally involved in walking and posture. It affects the entire lower limb and the movement of the hip and the lumbar area. It is a muscular district called to work during daily and sports activities and maintain orthostatism. This article reviews the anatomical and functional information of the gastrocnemius muscle and its embryological derivation. This review will also illustrate the vascular and lymphatic network and the innervating nerve branch. The text describes the concept of fascial continuum, which explains the influence of a muscular district compared to those bordering and distant.

It highlights the anatomical variants such as gastrocnemius tertius or quadriceps gastrocnemius. The text describes some pathological conditions and surgical approaches related to gastrocnemius and the muscle's instrumental and palpatory clinical evaluation. The paper concludes by describing conservative approaches in cases of calf dysfunction, such as physiotherapy and osteopathy.

The important reflection from the text is that a contractile district relates to the body system, and it is limiting to consider a muscle only as an anatomical segment.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

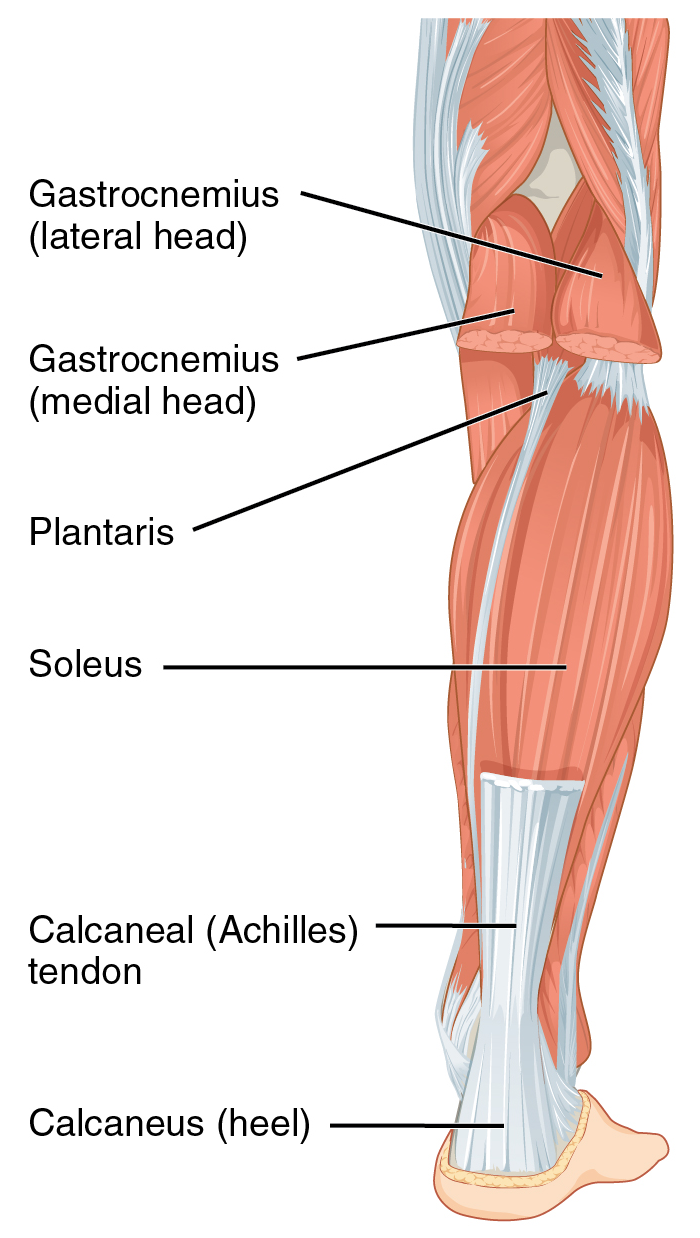

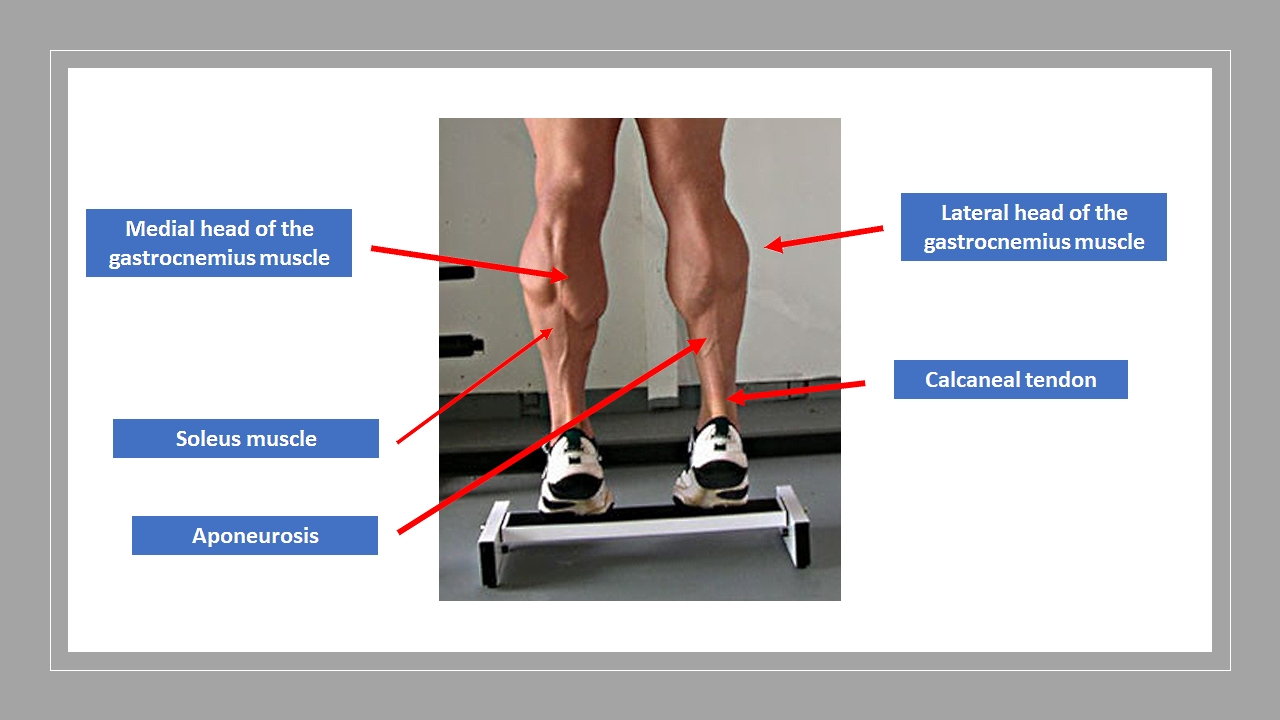

The muscle of the triceps surae is part of the muscles of the posterior area of the leg. It is comprised of three heads, two of which are superficial; the medial head and the lateral head, which form the gastrocnemius muscle, and a deeper muscle, the soleus muscle, and in a small percentage, the plantaris muscle.[1] The triceps surae determines the plantar flexion of the foot and its supination, and with the muscle heads that originate from the femur, it helps to flex the knee. It intervenes decisively in the posture of the foot (the sagittal plane) and walking, running, and jumping.[1] While walking, the quadriceps muscle and the gastrocnemius activate, particularly during the first phase of the foot support and the swing phase; in these movements, there is a complete extension of the knee. The gastrocnemius intervenes to stop the tibia translation forward while the quadriceps extend the knee.[2] The medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle intervenes with greater power in plantar flexion than the lateral head.[1] In a walk without running, it is the soleus muscle that intervenes most in the plantar flexion of the foot.[1]

Anatomy

- The medial head of the gastrocnemius originates from the epicondyle and the posterior surface of the medial condyle of the femur. We can identify a lateral origin and a medial origin. The latter involves a flattened, strong, thicker tendon, which contacts the upper area of the medial condyle, below the tendon's insertion of the muscle adductor magnus, and the medial supracondylar crest. The lateral origin has a short tendon in admixture with muscle fibers contacting the knee joint capsule and on the popliteal area of the medial femoral condyle. It knows this insertion zone as the medial supracondylar tubercle.[1] The medial head is generally thicker and wider than the lateral head. At the medial condyle of the femur/origin of the medial head, there is a serous bursa, which allows the proximal muscular body of the lateral head of the muscle to slide.[1] This bursa comes in contact with the bursa of the semimembranosus muscle, creating a functional link of continuity. The bursa involving the medial head may be the site of Baker's cyst.

- The lateral head of the gastrocnemius originates from the lateral surfaces of the epicondyle, in a posterior and lateral fossa, proximal to the popliteal muscle tendon, attaching to the lateral supracondylar crest.[1] Tendon and muscle fibers originate from the joint capsule of the knee and, in a lower percentage compared to the medial area, from a lateral supracondylar tubercle. In 10% to 30% of the population, there is a small sesamoid bone (Fabella), which is imbibed in the origin of the lateral head of the gastrocnemius. The fabella is covered by hyaline cartilage and is articulated with the lateral femoral condyle. It rarely connects with the medial head. It could play a role in stabilizing the knee. There are bursae similar to those found with the medial head (not as complex as the previous one and not always) at the level of the lateral head.[1]

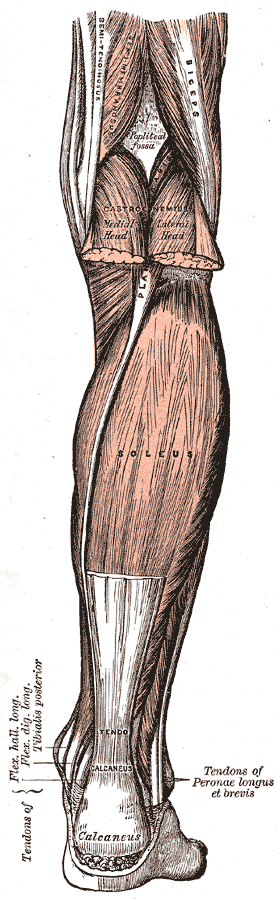

The two heads are directed downward, delimiting the popliteal fossa, and at the level of the middle third of the leg, they unite to constitute a large aponeurosis that completely covers the anterior area of the muscular bodies going downward. The aponeurosis continues distally as a calcaneal tendon. The gastrocnemius muscle is a bi-articular muscle and morphologically defined as pennate.

- The soleus muscle has a fibrous origin from the head and the posterior face of the fibula, from the soleus muscle line of the posterior face of the tibial bone, and the fibrous arch between the fibula head and the soleus muscle line—a wide, flattened belly forms from these origins, which continues in a large aponeurosis directed downward. At the level of the lower third of the leg, it joins the deep fascia of the aponeurosis of the gastrocnemius muscle, constituting the calcaneal ligament. The latter reaches the foot and inserts into the tuberosity of the heel; a mucous bursa separates the calcaneal bone and the deep face of the tendon; a second, more superficial bursa lies between the skin and the tendon (subcutaneous calcaneal bursa). The soleus muscle is mono-articular and is covered by the twins of the gastrocnemius.[1] See Figure 1.

The plantaris muscle, absent in about 10% of the population, inserts with a tendon lateral to the insertion of the calcaneal tendon (rarely joining); in cases of rupture of the calcaneal tendon, the plantaris muscle-tendon remains intact.

Embryology

At the eighth week of gestation, the skeletal muscles are formed. The gastrocnemius muscle derives from the paraxial mesoderm, the latter in the post-otic region from the somites. The somites differ in dermomyotome, sclerotomies, and myotomes.[3] The precursors of the muscles derive from the lips of the lateral dermatomyotome. The last stage of muscle development is identified by the presence of transverse striations, a typical sign of the maturation of the muscles.[3] At this stage, there are the myotubes (precursor cells of muscle fibers).

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The sural arteries (or twin arteries) are collateral arteries of the popliteal artery (which derive from the femoral artery). The sural arteries originate at the level of the popliteal fossa and nourish the twin muscles and the soleus. The fibular circumflex artery, derived from the collateral branches of the posterior tibial artery (which derives from the popliteal artery), nourishes some deep muscles, including the soleus.[4] The popliteal vein drains the venous blood from the gastrocnemius muscle. The popliteal vein is formed by the junction of the saphenous vein, posterior tibial veins, and anterior tibial veins on the lower edge of the popliteal muscle and the medial side of the popliteal artery. Ascending, it passes through the opening of the adductor to become the femoral vein.[5][6] The perforating veins that influence blood flow during calf contraction are called Cockett veins.[6]

The lymphatic vessels of the lower limb are divided into superficial and deep. The superficial vessels originate from the integuments, run subcutaneously, and are grouped into medial, lateral, and superficial gluteal collectors, which then flow into the superficial inguinal lymphatic grouping. The deep vessels originate from the bones, muscles, and joints to become satellites of the deep vessels, ending in the deep inguinal lymph nodes. The lumbar lymph nodes left, and right are the efferent vessels of the lateral aortic group of lumboaortic lymph nodes. They drain the sub-umbilical region of the abdominal wall, the pelvic wall, the perineal wall, the lower limb, and the vascularized territory from the splanchnic branches of the aorta.[7]

Nerves

The tibial nerve is the reference nerve structure for the gastrocnemius muscle.

Before dividing at the level of the upper corner of the popliteal fossa, in a tibial branch and a peroneal branch, these two nerves constitute the main trunk of the sciatic nerve; they are separated inside the sciatic by a fascial/adipose tissue or septum, known as the septum of Compton-Cruveilhier.[8]

The tibial nerve arises from the trunk of the sciatic nerve above the popliteal fossa and descends into the popliteal fossa between the two heads of the gastrocnemius, anterior to the soleus muscle; about 15 centimeters above the ankle, it travels medially to the calcaneal tendon and superficially.[9] In the calf, it innervates several contractile districts of the superficial and deep posterior compartment: the plantar, the gastrocnemius; the soleus; the tibialis posterior; the long flexor of the fingers; the long flexor of the hallux.[9]

Muscles

Myofascial Continuum

When talking about skeletal muscle, one should think not of a single district but a myofascial continuum. The gastrocnemius muscle tension is transmitted not only to the foot but to the knee, hip, and lumbar area, thanks to its fascial connections: the latter is the anatomical links with other tendons (insertion and origin) and the fascia covering muscles. A shortened gastrocnemius muscle could cause dysfunctions in the physiological movements of the hip, decreasing its anteversion.[10] The fascial system plays a fundamental role in transmitting the force produced by the contraction of the contractile component of the muscle.[11]

When the muscle contracts, the first tissue that receives the tension produced is the connective tissue of the muscle stroma. The tension travels along the axis of the fibers through the epimysium, up to the tendon (if the muscle has a fusiform morphology), with a longitudinal pattern. If the muscle is pennate, like the gastrocnemius, the force produced follows the interfilament inside the Z line of the sarcomeres, up to the sarcolemma, the extracellular matrix, and the epimysium (and hence the tendon); the vector has a transverse trajectory, and only later, follows the longitudinal structures of the epimysium.[12]

In the first case, with the fusiform muscles, the speed of arrival of the expressed force is rapid but less effective, while in the second case, with the pennate muscles, the arrival of force to the tendons is slower but with values of tension expressed more wide. For example, the biceps brachii is faster but weaker than the deltoid muscle, just as the gastrocnemius muscle is stronger than the soleus muscle, which is faster but less powerful.

The calcaneal tendon is the widest and longest tendon in the human body.[1] The tendon connects with the plantar fascia of the foot (from the calcaneus to the metatarsal heads), which is considered fundamental for the stability of the different tarsal joints. Dysfunction of the gastrocnemius muscle negatively affects the tension of the plantar fascia, altering the physiological support of the foot.[13]

Muscular Phenotypes

Another important difference between the gastrocnemius muscle and the soleus muscle is that the first muscle has a majority of anaerobic or white fibers, while the latter is rich in aerobic or red fibers.[14] In a movement that requires the expression of great power quickly, the gastrocnemius will be called to intervene. If walking is the main component of physical effort, it will be the soleus muscle that plays the main role.

Physiologic Variants

Nature and anatomy always reserve extraordinary adaptations and differences. The gastrocnemius does not escape the rule. One can find the gastrocnemius tertius, an accessory muscle district that is an integral part of the muscle, as well as an extra soleus muscle. Rarely, these accessory muscles can be found simultaneously and bilaterally, without effects on joint function and innervation by the tibial nerve. The gastrocnemius tertius could cause problems in the popliteal fossa if it should come into contact with the popliteal artery and create an arterial entrapment.[15]

There are anatomical variants in the literature. Specifically, it is possible to find a quadriceps gastrocnemius muscle. Practitioners do not know if this variant causes dysfunctions and pathologies; the tibial nerve innervates this variant.[16]

The gastrocnemius may present the absence of a head (in particular the lateral one) or be absent or present anomalies not in the number of heads but with respect to the area of origin.[16] A case of compression of the popliteal artery and popliteal vein is reported in the literature due to an anomaly of the origin of the lateral head of the gastrocnemius. This alteration led to the formation of a venous and arterial thrombus, resulting in secondary pulmonary hypertension.[17]

Surgical Considerations

One of the dangers during gastrocnemius muscle surgery is the accidental injury of the sural nerve. Furthermore, the patient may be unsatisfied with a poor cosmetic result. It is possible to divide the anatomical area for a surgical procedure into five levels, with the fifth level starting proximally and the last level ending distally.[1] The fifth level includes the origin of the two muscle heads of the popliteal area; the fourth level involves the muscular portion of the two heads (before arriving at the aponeurosis); the third level begins where the contractile fibers of the muscle merge with the aponeurosis until the fusion of the fascial area of the gastrocnemius and the soleus. The second level includes the aponeurosis of the gastrocnemius and the soleus, up to the distal part of the calcaneal tendon, before its insertion; the fifth and last level comprises the portion of the calcaneal tendon that involves the heel and its final insertion.[1]

Reconstruction

The medial head of the gastrocnemius can be used to detect an innervated flap; the latter is used for the recovery of several pathological pictures, such as the foot drop, muscular defects of the upper limbs, Volkmann contractures, and for the recovery of the movement of the tongue. In cases of post-surgical infection (replacement with knee joint prosthesis), a gastrocnemius muscle flap can be used to improve the clinical results of cicatrization. A medial head flap is used to improve the cicatrization of transtibial amputation intervention.[18] Using a part of the gastrocnemius muscle has few negative collaterals and fast use.[19]

Baker Cyst

This popliteal cyst comes from the doctor who first described it in 1877, surgeon William Morrant Baker. These cysts are formed in the presence of an already compromised knee joint (osteoarthritis, meniscal rupture), which creates effusions from the articulation toward the posterior area of the knee, toward the bursa of the medial head of the gastrocnemius. Often, there is a joint material in the cyst coming from inside the capsule; this transit of fluids is always unidirectional. Generally, they are asymptomatic and discovered with the magnetic resonance in a knee with known functional problems. Surgical excision is used only in limited cases, with a posterior approach.[20]

Injury of Muscle Fibers or Tearing

Muscle tearing or muscle distraction can be common for those who play sports. Depending on the severity of the injury, one can distinguish three types of calf muscle tears. The most serious is the third degree, which involves at least three-quarters of muscle mass. In first-degree injuries, when the lesions are modest and do not exceed 5% of muscle mass, there is no significant reduction in muscle function. The subject usually experiences a sensation of continuous cramping. In the second-degree lesion, the manifestations are those of pain; pain is felt during movement. Generally, the indications for the first two levels are conservative. In the third degree, muscular tear, hematomas, edema, and swelling may appear, the pain becomes very strong, and the subject is in a disabling condition because he can not move the leg. This lesion is felt on palpation as a depression, which testifies to the extent of the breakup.[1]

Achilles Tendon Disorders

Achilles tendon (or "calcaneal" tendon) disorders are relatively common injuries. Disorders can occur in adolescents and adults, and etiologies include traumatic and nontraumatic mechanisms. The spectrum of pathology ranges from insertional tendinitis, intra-substance tears and/or tendinopathy, and partial versus complete ruptures.[21]

Acute ruptures of the Achilles tendon may be misdiagnosed in up to 25% of cases. The most common misdiagnosis is that of an ankle sprain. Missed or delayed diagnosis can be problematic for patients, and a chronically dysfunctional tendon is harder to repair surgically.[22] Acute and sudden pain in the calcaneal tendon, the functional impotence, and the palpatory sensation of the interruption of the tendon are the basis of the diagnostic suspicion confirmed by the ultrasound investigation. This injury is the consequence of chronic tendinitis, often unrecognized or undervalued. Other causes may be related to systemic diseases (diabetes, lupus erythematosus) or chronic administration of steroid drugs.[23] Collagen fibers change their phenotype; with increased collagen type III, they are less elastic and less able to handle mechanical stresses.

The injury mainly involves jumpers, runners, soccer players, and tennis players, realized as a consequence of a sharp muscle contraction. Treatment is surgical. Many types of tendon suture can be performed. The calcaneal tenorrhaphy is now performed with a technique that uses tiny incisions to avoid the scarring disorders related to very long incisions and the benefit of reduced recovery times. Sometimes, a reinforcing plastic is made using the tendon of the gracilis muscle plantar or the peroneus longus muscle tendon.[22]

Gastrocnemius Shortening

Several diseases cause a shortening of the gastrocnemius muscle: lesions of the nervous system, central or peripheral, hereditary diseases such as myopathy and dystrophies, or acquired disease like diabetes. All age groups can be involved, from the children to the elderly. The most evident functional disturbance of this shortening is the equine foot, where the tip of the foot points toward the bottom, and the gait is characterized by the toe of the foot to the ground. First of all, it is essential to distinguish the cause of equinism, evaluate its characteristics in walking, and establish an appropriate treatment. The treatment uses conservative methods (physiotherapy, stretching, tutors, botulinum toxin) and surgical methods, such as stretching the calcaneal tendon.

The Silfverskiold test makes it possible to discriminate whether the equinism is caused by a retraction of the soleus muscle (extended knee) or the gastrocnemius muscle (flexed knee). If the ankle can be dorsiflexed with the knee bent at 90 degrees but can not be dorsiflexed with the extended knee, it is probable that the gastrocnemius muscle is shortened, but not the soleus; it can be done with a patient sitting or lying on the back.

The most recent surgical procedures use endoscopy to reduce collateral damage by creating a small cut at leg level 4; the release of the calcaneal tendon could produce an evaluation error with an excessive elongation of muscle.[24][25]

Clinical Significance

The clinician should first observe how the patient moves, how he compensates, and whether there are any differences in muscle shape between the two calves. The clinician will palpate the tone of the muscles, both on the fleshy level and on the fascia (aponeurosis and tendon); the movement is first activated by the patient so as not to condition the person or the perception of pain. Passively evaluate the knee and ankle after active movements. Finally, the anamnesis will be fundamental.

Correct Evaluation of the Equine Foot

To perform the Silfverskiold test correctly, the force applied by the operator must be about 2 kilos, with the hand placed under the sole or under the head of the second metatarsal. If the patient has a non-rigid flat foot, the heel is in a position of valgism; in this case, pure dorsiflexion does not occur, with a movement that expresses itself on an oblique plane, thanks to the joints of the hindfoot. To obtain a clean movement and to improve the execution of the test, the hindfoot must be placed in a neutral or slightly variant position. Before performing this test, it is possible to carry out the Taloche test or the Taloche sign. If the gastrocnemius muscle is contracted, the patient will not be able to maintain the orthostatism if it is resting on an inclined plane (a tablet).[26]

Tibial Nerve Trapping

A tibial nerve tract can be palpated both in the popliteal cavity and slightly below; in these areas, it is superficial and very simple to hear manually. The nerve becomes the posterior tibial nerve when it reaches the ankle area and travels in the tarsal tunnel, deeper than the flexor retinaculum and the posterior tibial artery and vein.[9] Another point of contact with the tibial nerve is behind the medial malleolus, just below and medially the calcaneal tendon; with the thumb, look for the malleolus and slowly bring a finger toward the tendon with a horizontal pattern. It is often a painful area of which the patient is unaware.

The tibial nerve rarely undergoes an entrapment to the popliteal cavity, while it more frequently has an entrapment to the tarsal tunnel, as previously mentioned. At this level, there are different causes such as a tumor, a previous intervention, trauma, systemic diseases such as diabetes or neurological diseases, and deformity of the same foot. It is possible to carry out a stress test with the Tinel test to evoke the painful or paresthesia symptoms.[9]

Calcaneal Tendon Rupture Evaluation

The Thompson squeeze test or sign of Simmonds-Thompson is a semiotics maneuver of the objective examination of the lower limb, which, if positive, indicates a complete rupture of the calcaneal tendon. The examiner compresses the patient's calf between the fingers, lying in a prone position with the feet over the edge of the bed. Under normal conditions, the squeezing of the muscular masses causes the plantar flexion of the foot, while when there is a full-thickness tear of the posterior calcaneal tendon structures, it evokes intense pain with no movement of the foot.[27]

Other Issues

Physiotherapy for Tears: First and Second Degree

With an anatomical lesion, the treatment in the first 24 to 48 hours consists of the RICE protocol (Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation). This treatment avoids the aggravation of the lesion and inflammation. This protocol includes rest, ice 3 to 4 times a day for 20 minutes, bandaging, and elevation of the limb.

Generally, muscle relaxants and analgesics are taken, the latter being preferable to anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) because post-injury inflammation is a physiological mechanism of repair of the human body. The athlete must stay away from the field for a variable time depending on the size of the injury, ranging from 1 week to 2 months.[28]

After an injury, the muscle closes the lesion forming a fibrous cicatricial result, that is, a less elastic connective tissue of the muscle. If the muscle is immobilized, the scar is formed with fibers that can go in any direction; if, instead, the muscle is kept moving, the fibers of the connective tissue that is formed have an arrangement according to the lines of force and are more elastic. Instrumental physiotherapy with CO2 laser, ultrasound, and Tecar therapy is indicated; when the lesion is closed, activity is needed to make the muscle more elastic and prevent recurrences. Stretching and eccentric reinforcement are important. In general, the elective exam is muscle-tendon ultrasound, but magnetic resonance may be necessary if the lesion is deep in a very developed muscle.[28]

Rupture of the Calcaneal Tendon

The rehabilitation treatment of calcaneal tendon rupture has a duration of about 12 weeks, at three sessions per week, alternating between the gym and swimming pool, including massage on the scar and the calf muscles, physical therapies for pain and swelling, exercises for the articulation, for restoring strength and correct walking and running.[22]

After about three months, it is possible to perform an isokinetic test to measure the muscular strength of the leg. Based on the result, the therapeutic protocol must adapt to the athlete's sport to speed up the return, refining the recovery of the coordination of the specific technical gesture of the sport practiced.[29]

Kinesio Taping

The application of elastic bands on the muscle tissue could be helpful for some conditions of the gastrocnemius muscle. In the presence of trigger points, taping has proved useful in reducing symptomatology.[30]

It would seem that the use of taping on the calcaneal tendon has a rationale for preventing sports injuries.[31]

Osteopathy

The osteopathic approach with gentle techniques in the presence of scars may help prevent further pain and improve function.[32]

Osteopathy in patients with tendinitis has proven to help reduce symptomatology and improve the active movement of plantar flexion.[33]

Popliteal Fossa: An Important Area for the Function of the Gastrocnemius Muscle

In the popliteal fossa, a fundamental site for the gastrocnemius muscle, it is possible to find tensor fasciae suralis (also known as ischioaponeuroticus), a muscle that could disturb the function of the calf area and is clinically relevant. One of the variants of the tensor fasciae suralis muscle is to extend over the lateral head of the gastrocnemius muscle, innervated by the common peroneal nerve. The abnormal presence of this muscle could alter the function of the gastrocnemius, with dysfunctional problems in the knee and ankle, with repeated traumas in these articular areas. This is because the lines of tension are altered and do not allow the joints to withstand the workloads correctly, from running to jumping.

Another muscle variable that could alter the function of the gastrocnemius muscle is a strip of muscle (it does not have a name) that goes from the medial head transversely to the tendon tissue of the biceps femoris; this anomaly is innervated by the tibial nerve. This muscular structure covers the neurovascular components of the popliteal fossa. Its hypertrophy could cause paresthesia, entrapment of the popliteal artery, and create abnormal tensions for the correct function of the calf area.

A Baker cyst in the popliteal fossa could mimic a problem of deep vein thrombosis. An examination with ultrasound may not be sufficient to understand the reasons for the pain (for example, in the area of insertion of the gastrocnemius muscle when bending the knee). A further consideration is the MRI. If the pharmacological therapy for thrombosis does not remove the pain from the popliteal fossa, one of the etiologies reported in the literature is the presence of this cyst.

Dry Needling

Clinicians and physiotherapists use dry needling to improve the muscular response to previous sports injuries or for the presence of trigger points. They are easy-to-use tools and, according to literature, can increase the muscular performance of the gastrocnemius muscle in sports subjects or the presence of neurological pathology.[34][35]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Dalmau-Pastor M, Fargues-Polo B Jr, Casanova-Martínez D Jr, Vega J, Golanó P. Anatomy of the triceps surae: a pictorial essay. Foot and ankle clinics. 2014 Dec:19(4):603-35. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2014.08.002. Epub 2014 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 25456712]

Mengarelli A, Gentili A, Strazza A, Burattini L, Fioretti S, Di Nardo F. Co-activation patterns of gastrocnemius and quadriceps femoris in controlling the knee joint during walking. Journal of electromyography and kinesiology : official journal of the International Society of Electrophysiological Kinesiology. 2018 Oct:42():117-122. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2018.07.003. Epub 2018 Jul 17 [PubMed PMID: 30025300]

Warmbrunn MV, de Bakker BS, Hagoort J, Alefs-de Bakker PB, Oostra RJ. Hitherto unknown detailed muscle anatomy in an 8-week-old embryo. Journal of anatomy. 2018 Aug:233(2):243-254. doi: 10.1111/joa.12819. Epub 2018 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 29726018]

Dusseldorp JR, Pham QJ, Ngo Q, Gianoutsos M, Moradi P. Vascular anatomy of the medial sural artery perforator flap: a new classification system of intra-muscular branching patterns. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2014 Sep:67(9):1267-75. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2014.05.016. Epub 2014 May 20 [PubMed PMID: 24957803]

Fathi M, Hassanzad Azar M, Arab Kheradmand A, Shahidi S. Anatomy of arterial supply of the soleus muscle. Acta medica Iranica. 2011:49(4):237-40 [PubMed PMID: 21713734]

Baliyan V, Tajmir S, Hedgire SS, Ganguli S, Prabhakar AM. Lower extremity venous reflux. Cardiovascular diagnosis and therapy. 2016 Dec:6(6):533-543. doi: 10.21037/cdt.2016.11.14. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28123974]

Pan WR, Wang DG, Levy SM, Chen Y. Superficial lymphatic drainage of the lower extremity: anatomical study and clinical implications. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2013 Sep:132(3):696-707. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31829ad12e. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23985641]

Sladjana UZ, Ivan JD, Bratislav SD. Microanatomical structure of the human sciatic nerve. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2008 Nov:30(8):619-26. doi: 10.1007/s00276-008-0386-6. Epub 2008 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 18648720]

Donovan A, Rosenberg ZS, Cavalcanti CF. MR imaging of entrapment neuropathies of the lower extremity. Part 2. The knee, leg, ankle, and foot. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2010 Jul-Aug:30(4):1001-19. doi: 10.1148/rg.304095188. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20631365]

Cruz-Montecinos C, González Blanche A, López Sánchez D, Cerda M, Sanzana-Cuche R, Cuesta-Vargas A. In vivo relationship between pelvis motion and deep fascia displacement of the medial gastrocnemius: anatomical and functional implications. Journal of anatomy. 2015 Nov:227(5):665-72. doi: 10.1111/joa.12370. Epub 2015 Sep 10 [PubMed PMID: 26467242]

Bordoni B, Zanier E. Clinical and symptomatological reflections: the fascial system. Journal of multidisciplinary healthcare. 2014:7():401-11. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S68308. Epub 2014 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 25258540]

Huijing PA, Yaman A, Ozturk C, Yucesoy CA. Effects of knee joint angle on global and local strains within human triceps surae muscle: MRI analysis indicating in vivo myofascial force transmission between synergistic muscles. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2011 Dec:33(10):869-79. doi: 10.1007/s00276-011-0863-1. Epub 2011 Sep 13 [PubMed PMID: 21912991]

Pascual Huerta J. The effect of the gastrocnemius on the plantar fascia. Foot and ankle clinics. 2014 Dec:19(4):701-18. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2014.08.011. Epub 2014 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 25456717]

Moss CL. Comparison of the histochemical and contractile properties of human triceps surae. Medical & biological engineering & computing. 1992 Nov:30(6):600-4 [PubMed PMID: 1297014]

Yildirim FB, Sarikcioglu L, Nakajima K. The co-existence of the gastrocnemius tertius and accessory soleus muscles. Journal of Korean medical science. 2011 Oct:26(10):1378-81. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2011.26.10.1378. Epub 2011 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 22022193]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAshaolu JO, Oni-orisan OA, Ukwenya VO, Opabunmi OA, Ajao MS. The quadriceps gastrocnemius muscle. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2014 Dec:36(10):1101-3. doi: 10.1007/s00276-013-1248-4. Epub 2013 Dec 15 [PubMed PMID: 24337388]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWang M, Zhang S, Wu X, Jin X, Zhang J. Popliteal vascular entrapment syndrome caused by variant lateral head of the gastrocnemius muscle leading to pulmonary artery embolism. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2012 Nov:25(8):986-8. doi: 10.1002/ca.22039. Epub 2012 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 22467429]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTosun B, Selek O, Gok U, Tosun O. Medial gastrocnemius muscle flap for the reconstruction of unhealed amputation stumps. Journal of wound care. 2017 Aug 2:26(8):504-507. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2017.26.8.504. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28795882]

Walton Z, Armstrong M, Traven S, Leddy L. Pedicled Rotational Medial and Lateral Gastrocnemius Flaps: Surgical Technique. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2017 Nov:25(11):744-751. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00722. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29059111]

Frush TJ, Noyes FR. Baker's Cyst: Diagnostic and Surgical Considerations. Sports health. 2015 Jul:7(4):359-65. doi: 10.1177/1941738113520130. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26137182]

Weinfeld SB. Achilles tendon disorders. The Medical clinics of North America. 2014 Mar:98(2):331-8. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2013.11.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24559878]

Gross CE, Nunley JA. Treatment of Neglected Achilles Tendon Ruptures with Interpositional Allograft. Foot and ankle clinics. 2017 Dec:22(4):735-743. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2017.07.010. Epub 2017 Sep 28 [PubMed PMID: 29078825]

Maffulli N, Irwin AS, Kenward MG, Smith F, Porter RW. Achilles tendon rupture and sciatica: a possible correlation. British journal of sports medicine. 1998 Jun:32(2):174-7 [PubMed PMID: 9631229]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTennant JN, Amendola A, Phisitkul P. Endoscopic gastrocnemius release. Foot and ankle clinics. 2014 Dec:19(4):787-93. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2014.08.009. Epub 2014 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 25456722]

Solan MC,Carne A,Davies MS, Gastrocnemius shortening and heel pain. Foot and ankle clinics. 2014 Dec [PubMed PMID: 25456718]

Barouk P, Barouk LS. Clinical diagnosis of gastrocnemius tightness. Foot and ankle clinics. 2014 Dec:19(4):659-67. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2014.08.004. Epub 2014 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 25456715]

Scott BW, al Chalabi A. How the Simmonds-Thompson test works. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 1992 Mar:74(2):314-5 [PubMed PMID: 1544978]

Nsitem V. Diagnosis and rehabilitation of gastrocnemius muscle tear: a case report. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association. 2013 Dec:57(4):327-33 [PubMed PMID: 24302780]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBrumann M, Baumbach SF, Mutschler W, Polzer H. Accelerated rehabilitation following Achilles tendon repair after acute rupture - Development of an evidence-based treatment protocol. Injury. 2014 Nov:45(11):1782-90. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2014.06.022. Epub 2014 Jul 7 [PubMed PMID: 25059505]

Kalichman L, Levin I, Bachar I, Vered E. Short-term effects of kinesio taping on trigger points in upper trapezius and gastrocnemius muscles. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies. 2018 Jul:22(3):700-706. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2017.11.005. Epub 2017 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 30100299]

Tsai FH, Chu IH, Huang CH, Liang JM, Wu JH, Wu WL. Effects of Taping on Achilles Tendon Protection and Kendo Performance. Journal of sport rehabilitation. 2018 Mar 1:27(2):157-164. doi: 10.1123/jsr.2016-0108. Epub 2018 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 28253065]

Racca V, Bordoni B, Castiglioni P, Modica M, Ferratini M. Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment Improves Heart Surgery Outcomes: A Randomized Controlled Trial. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2017 Jul:104(1):145-152. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.09.110. Epub 2017 Jan 18 [PubMed PMID: 28109570]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHowell JN, Cabell KS, Chila AG, Eland DC. Stretch reflex and Hoffmann reflex responses to osteopathic manipulative treatment in subjects with Achilles tendinitis. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 2006 Sep:106(9):537-45 [PubMed PMID: 17079523]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBenito-de-Pedro M, Calvo-Lobo C, López-López D, Benito-de-Pedro AI, Romero-Morales C, San-Antolín M, Vicente-Campos D, Rodríguez-Sanz D. Electromyographic Assessment of the Efficacy of Deep Dry Needling versus the Ischemic Compression Technique in Gastrocnemius of Medium-Distance Triathletes. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland). 2021 Apr 21:21(9):. doi: 10.3390/s21092906. Epub 2021 Apr 21 [PubMed PMID: 33919195]

Valencia-Chulián R, Heredia-Rizo AM, Moral-Munoz JA, Lucena-Anton D, Luque-Moreno C. Dry needling for the management of spasticity, pain, and range of movement in adults after stroke: A systematic review. Complementary therapies in medicine. 2020 Aug:52():102515. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2020.102515. Epub 2020 Jul 16 [PubMed PMID: 32951759]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence