Introduction

While some have argued that human hair is a vestigial evolutionary remnant, in reality, human hair serves many psychological and physiological functions. Human hair grows at a rate of 0.35 mm/day, and around 100 hairs are shed daily. Human hair angiogenesis begins at about ten weeks of gestation, and final development results in the mature hair follicle. The pilosebaceous unit comprises the sebaceous gland, the arrector pili muscle, and the hair follicle. The clinical significance of hair includes increased hair loss disorders, complete hair loss disorders, and other conditions. Hair loss is often accompanied by psychological strife, which should be addressed and monitored by clinicians.[1][2]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Hair serves many functions, including thermoregulation and protection. In animals and nonhuman primates, hair maintains temperature by retaining heat or preventing cold. Hair can also provide camouflage and serve as a sexual attractant. In humans, hair is thinner and lighter than in primates. Human hair aids in sweating thermoregulation and serves as a sense organ. Hair also protects from the elements, including UV radiation. Additionally, humans have specialized hair, such as eyelash hair and eyebrow hair. Finally, the role of hair in human psychology is essential, and an individual’s hair plays a critical role in his or her identity and self-evaluation. The psychological function of hair is particularly evident in hair loss disorders such as alopecia.[3][4]

Embryology

At around ten weeks gestational age, hair angiogenesis begins. First, focal thickenings in the scalp and face, called placodes, form. These placodes extend deeper into the dermis and differentiate into the hair germ and a dermal condensate cap. As the hair germ extends, the hair bulb epithelium encapsulates the dermal condensate to form the dermal papillae. Eventually, layers form into the outer root sheath, the inner root sheath, the hair shaft cuticle, the cortex and the medulla. This structure becomes the hair follicle, with an accompanying sebaceous gland and the apocrine gland. Recent studies have shown vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) to be a key mediator in hair angiogenesis. [5]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

As the hair follicle develops, blood vessels originating from the deep dermal vascular plexus surround it. These vessels nourish the hair follicle and support nutrient delivery, waste elimination, and growth. Loss of blood supply to the hair follicles is associated with some forms of hair loss. Additionally, anagen hair follicles have demonstrated angiogenic properties. While the relationship has not been well defined, the blood supply is an essential component of successful hair follicle growth, maturation, and maintenance. The lymphatic vasculature within the dermis supplies the hair follicles as well and participates in the skin immune response.

Nerves

Two neural networks innervate hair and hair follicles, and both contain sensory nerve fibers and autonomic nerve fibers. One of the neural networks is made up of sensory C fibers and sympathetic fibers and surrounds the neck of the hair follicle. The other is made up of longitudinal A-delta fibers and circular C fibers and encircle the midsection of the hair follicle, between the isthmus and the sebaceous gland. Nearby nerves also innervate the proximal arrector pili muscles.

Muscles

The primary muscle that serves hair is the arrector pili muscle. This muscle develops independently of the hair follicle near the sebaceous gland and connects to the hair follicle at the hair follicle bulge. Each hair follicle growing parallel to the skin attaches to the connective tissue of the basement membrane by the small band of muscle known as the arrector pili. Hairs growing perpendicular to the skin, such as eyelash hairs, do not have associated arrector pili. The function of these muscles is to mediate thermoregulation by contracting and raising or relaxing and releasing the hair. Recent research indicates that elevating and lowering the hairs may also provide some support to the hair follicle’s integrity and stability, but the precise mechanism of this relationship is yet undiscovered.

Physiologic Variants

Healthy hair growth occurs at a rate of 0.35 mm/day, which sums to approximately 0.5 in/mo or 6 in/yr. Most healthy men and women have 80,000 to 120,000 terminal hairs on their scalp. Hair follicles cycle through three primary phases: anagen, catagen and telogen phases. The anagen or growth phase lasts 2 to 6 years, during which primary hair growth occurs. At any given time, somewhere between 85% and 90% of hair follicles are in this growth phase. Follicular regression characterizes the catagen, or transitional, stage of a hair follicle. The telogen phase is a resting phase that lasts approximately three months. After these three phases, the inactive or dead hair is shed. The scalp sheds 100 hairs each day and can shed more with shampooing or other hair care practices. Hair follicles that deviate from this normal physiology result in pathological conditions such as alopecia or telogen effluvium.

Clinical Significance

The clinical significance of hair cannot be understated, and there are many pathologies associated with hair. These pathologies can be split into two separate processes: effluvium and alopecia. Effluvium describes increased hair loss, which patients may describe as their hair "falling out.” Alopecia describes hairlessness, which patients may describe as (or demonstrate) areas with complete loss of hair. The most common hair pathologies will be briefly considered herein. [6][7][8]

Androgenetic alopecia is the most common presenting hair concern and affects 50 million men and 30 million women in the United States alone. It is colloquially referred to as male pattern baldness. Studies estimate that 70% of men and 40% of women are affected by androgenetic alopecia. Men will classically present with receding temporal hairlines, described as hair thinning and loss in an “M” shape. Women will typically present with a widening part and thinning at the top of the scalp. A genetic predisposition to increased hair follicle sensitivity to circulating androgens causes this type of hair loss.

Alopecia describes complete hair loss. This can occur on the entire scalp (alopecia totalis) or body (alopecia universalis) or may be localized to specific areas (alopecia areata). Alopecia areata can progress to alopecia totalis and often begins acutely and spreads gradually over the course of weeks to months. Alopecia is an autoimmune disease mediated by T lymphocytes and other immune cells.

Telogen effluvium describes a disruption in the normal hair growth and rest cycles that results in excessive shedding and hair loss. This disorder is diagnosed by the hair pull test, which is positive when pulled hair easily is removed from the scalp, and 50% or more of the strands are in the telogen, or inactive, phase. This condition can be precipitated by physical stress, such as surgery or malnutrition, or by medical exposure, such as chemotherapy and common medications.

When taking history in a patient with hair loss, it is imperative to determine what the patient is experiencing. Hair loss can refer to increased daily hair loss, which a clinician will elicit by asking if the patient notices more hair on his or her pillow or more hair in the shower after bathing. Hair loss can also refer to apparent hairlessness, which a clinician will elicit by asking if the patient notices areas without hair or regions where hair seems to be less thick or provide less coverage. Teasing out this distinction is necessary to determine the correct diagnosis.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

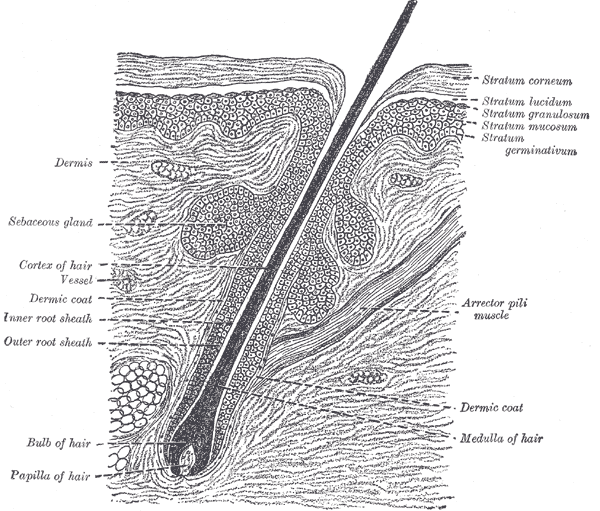

The Common Integument, Section of the Skin. A section of the skin showing the epidermis, dermis, hair shaft and follicle, arrector pili muscles, and sebaceous glands.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

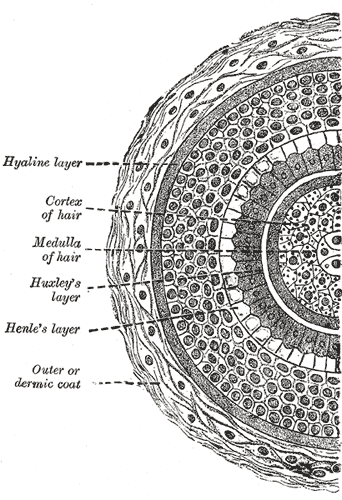

Transverse Section of a Hair Follicle. This transverse hair follicle section shows the hyaline layer, hair cortex and medulla, Huxley and Henle layers, and outer or dermic coat.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Kabashima K, Honda T, Ginhoux F, Egawa G. The immunological anatomy of the skin. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2019 Jan:19(1):19-30. doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0084-5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30429578]

Park AM, Khan S, Rawnsley J. Hair Biology: Growth and Pigmentation. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2018 Nov:26(4):415-424. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2018.06.003. Epub 2018 Aug 16 [PubMed PMID: 30213423]

Breehl L, Caban O. Physiology, Puberty. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30521248]

Grubbs H, Nassereddin A, Morrison M. Embryology, Hair. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30521215]

Yano K, Brown LF, Detmar M. Control of hair growth and follicle size by VEGF-mediated angiogenesis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2001 Feb:107(4):409-17 [PubMed PMID: 11181640]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceQureshi A, Friedman A. Comorbidities in Dermatology: What's Real and What's Not. Dermatologic clinics. 2019 Jan:37(1):65-71. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2018.07.007. Epub 2018 Nov 1 [PubMed PMID: 30466689]

Yu V, Juhász M, Chiang A, Atanaskova Mesinkovska N. Alopecia and Associated Toxic Agents: A Systematic Review. Skin appendage disorders. 2018 Oct:4(4):245-260. doi: 10.1159/000485749. Epub 2018 Jan 5 [PubMed PMID: 30410891]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDina Y, Aguh C. Algorithmic approach to the treatment of frontal fibrosing alopecia: A systematic review. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2021 Aug:85(2):508-510. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.10.043. Epub 2018 Oct 28 [PubMed PMID: 30393097]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence