Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection

Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection

Introduction

Congenital cytomegalovirus (CCMV) infection is the most common intrauterine infection in the U.S. and the most common cause of non-genetic sensorineural hearing loss in children.[1][2] Most of the time, the disease is asymptomatic (85 to 90%).[3][4] The symptomatic congenital disease occurs most often after primary maternal infection in pregnancy. Although significantly less common, symptomatic CCMV carries a mortality risk of up to 7 to 12% in the early neonatal period. There is an increased risk of severe morbidity due to CNS damage, leading to neurodevelopmental delays, hearing loss, and vision impairment. Asymptomatic disease is not entirely benign as 10 to 15% go on to develop long term morbidities.[4][5] Despite these risks, there is poor awareness of CCMV among women of reproductive age.[6][7]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is the largest member of the herpes viridae family (HHV-5), and humans are the main reservoir. The virus sheds in bodily fluids such as saliva, urine, breast milk, semen, and blood. Primary infection of the host occurs when a previously uninfected individual acquires the disease for the first time. In addition to primary infection, there can also be latent or non-primary infections. Non-primary infections result from reactivation of a previous infection or infection with a different strain of the virus.[8] Hormonal changes associated with pregnancy and lactation may stimulate reactivation of CMV. Primary infection is associated with the greatest risk of transplacental transmission (30 to 35%),[2][9] compared to 1.1 to 1.7% for non-primary infections.[10] However, due to the relatively high seroprevalence rates, CCMV usually results from non-primary maternal infections.[2][11]

An important risk factor for primary infection during pregnancy is prolonged exposure to young children.[12] CMV infected children under 2 years of age secrete the virus in their urine and saliva for about 24 months.[13] Shedding of CMV in urine and cervicovaginal secretions increases as pregnancy progress. Thus, the transmission of the disease is more likely at more advanced pregnancy stages (58 to 78% in the third trimester compared to 30 to 45% in the first trimester).[14][15] However, long-term sequelae are less likely to occur if the fetus is infected later in pregnancy (24 to 26% if infected in the first trimester, and 2.5 to 6% if infected after 20 weeks).[16][17]

Epidemiology

Seroprevalence rates in women of reproductive age differ based on socioeconomic status. In developed countries, the seroprevalence rate ranges from 40 to 83%,[18] but in developing countries, the seroprevalence rate is almost 100%.[10] However, in lower socioeconomic groups in developed countries, the seroprevalence rate approaches that seen in developing countries. Acquisition of CMV in industrialized nations is usually due to frequent contact with small children while in the developing world, transmission occurs early in life through breastfeeding and crowded living conditions.[19] The live birth prevalence rate in developed countries is 0.6 to 0.7%, resulting in about 40000 cases annually in the United States.[20] The incidence of CCMV is higher in developing countries – between 1 and 5%. However, only about 10% are symptomatic as neonates, making the disease difficult to detect. The risk of long-term neurological sequelae increases in symptomatic babies with 40-58% developing permanent sequelae such as sensorineural hearing loss, ophthalmological deficits, and neurodevelopmental delays.[21] The commonest complication of CCMV infection is hearing loss; 35% in symptomatic newborns and 7 to 10% in asymptomatic newborns.[19][22]

History and Physical

Maternal CMV infection is frequently asymptomatic. Primary infection cannot clinically be distinguished from Epstein Barr virus (EBV) infection and presents with symptoms that include fever, malaise, headache, pharyngitis, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, arthralgias, and rash.

Fetal abnormalities include intracranial calcifications, microcephaly, ventriculomegaly, lenticulostriate vasculopathy, occipital horn anomalies, echogenic bowel, intrauterine growth restriction, hepatomegaly, pericardial effusion, and ascites. Also noted are placental inflammation and fetal death.[2][23] The most common signs of congenital cytomegalovirus in the neonate are jaundice, petechiae, hepatosplenomegaly, and microcephaly.[4][5][20][24][25] Other findings include chorioretinitis with or without optic atrophy and cataracts. Newborns could be premature or small for gestational age, or both. Hearing loss, which is the hallmark of CCMV may be present at birth or present later in life; this underscores the importance of regular hearing screens in children affected by CCMV.

Laboratory findings include elevated aspartate transferase, conjugated hyperbilirubinemia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated CSF protein.[24] Cranial imaging findings include periventricular calcifications, ventricular dilatation, ventricular cysts, and lenticulostriate vasculopathy.[20][22]

Evaluation

Diagnosis can occurs in two settings – prenatal and postnatal. Prenatal diagnosis involves testing of the mother and fetus.

Universal screening for CMV in pregnancy is currently not a recommendation due to a lack of tests with high enough sensitivity and specificity, as well as limited options for intervention. However, in certain circumstances, testing is advisable. Such circumstances include mononucleosis-like illness in pregnancy, exposure to an individual with CMV infection, occupational exposure (health or childcare worker) or fetal ultrasound suggestive of congenital CMV infection such as the presence of ventriculomegaly, hyperechogenic bowel, intracranial calcifications, and hydrops.[26] In cases of suspected primary CMV infection, maternal and fetal testing is necessary.

Maternal testing involves determining the maternal antibody status. A definitive diagnosis of primary CMV infection is obtained if there is seroconversion from a previously negative antibody status to an antibody positive status.[27] Since routine screening is not currently the standard of care, this conversion often gets missed. The presence of IgM antibodies suggests primary infection; however, IgM antibodies can persist for several months. More sophisticated testing such as IgG antibody avidity testing is necessary for sorting out the timing of infection. With recent infections, the avidity is low (antibodies bind less tightly with their protein); thus the presence of IgM levels along with a low IgG avidity index is highly suggestive of a recent primary infection.[8]

Fetal diagnosis is achieved via amniocentesis for amniotic fluid PCR with or without viral culture. Replication of the virus in the fetal kidney, leading to shedding in the urine, occurs at least 5 to 7 weeks after infection. Thus, the optimal time for performing this test is after 21 weeks gestation and 7 weeks after maternal infection.[8] The sensitivity of amniocentesis after 21 weeks is about 71% and 30% if done before 21 weeks.[28] A fetal sonogram is also a recommended procedure; however, the possible findings are not specific for CMV and are present in only around 15% of infected fetuses.[29] The presence of ultrasound abnormalities along with primary maternal infection strongly suggests fetal infection.[29] Cordocentesis for fetal IgM testing is not recommended due to poor sensitivity of the test and risk involved. A positive test on cordocentesis is always followed by a positive test on amniocentesis suggesting that amniocentesis without cord blood testing is adequate for diagnosing fetal CMV infection.[30] Viral load of CMV in the amniotic fluid may be determined for prognostic value. Higher CMV DNA load over 100000 correlates with symptoms in the newborn.[31]

Unless there is a high index of suspicion, CCMV often goes undetected at birth since most infected newborns are asymptomatic. Testing involves isolation of virus from urine or saliva via culture or DNA PCR within the first 3 weeks of life. After 3 weeks, it is not possible to determine the timing of infection – congenital vs. intrapartum or postnatal from breast milk or blood transfusion. Intrapartum or postnatal disease are not usually associated with long term sequelae.[9] There is a risk of PCR contamination with CMV positive breast milk, so ideally testing should be done more than 1 hour after breastfeeding.[32] Further evaluation of a newborn with CCMV should include complete blood count, hepatic panel, serum bilirubin (total and direct), and cranial imaging (ultrasound as the first test, may be followed by MRI if needed).[25]

Treatment / Management

There is no definitive way to treat congenitally acquired CMV in utero. For fetuses with positive isolation of the virus, termination of the pregnancy can be offered to parents. This offer must be accompanied with thorough counseling to enable the parents to make an informed decision. If the parents opt to continue the pregnancy, close follow up with regular ultrasound exams is essential. The use of CMV hyperimmune globulin (CMV HIG) as a method of prevention, could reduce the number of congenitally infected newborns compared to no treatment.[33] However, since concerns remain as to efficacy and toxicity, routine use is not recommended.[34](A1)

At birth, the newborn must be tested within 3 weeks of delivery via saliva or urine PCR or culture. If the diagnosis is confirmed, close follow up should be ensured for symptomatic neonates. Asymptomatic neonates also required to follow up, in particular, regular hearing screens. Pediatric subspecialists that have a role to play in the care of congenitally infected neonates include audiologists, otolaryngologists, ophthalmologists, neurologists, development/behavior specialists, infectious disease specialists, and physical/occupational therapists.[25]

Neonates with symptomatic CCMV should receive oral valganciclovir for 6 months. This therapy has been shown to preserve normal hearing or prevent the progression of hearing loss, and also correlates with improved long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes.[35] Oral Valganciclovir is superior to intravenous Ganciclovir, which is associated with bone marrow suppression (manifesting as neutropenia) and gonadal toxicity.[36] For both asymptomatic and symptomatic newborns, close follow up is vital to monitor for the development of long-term sequelae.(A1)

Differential Diagnosis

Other TORCH infections include toxoplasmosis, rubella, HSV, and syphilis.[9][37] Toxoplasmosis usually presents with chorioretinitis, microphthalmia, hydrocephalus, scattered calcifications, and maculopapular rash. Newborns with congenital rubella syndrome have cataracts and congenital heart disease. A vesicular rash usually distinguishes Herpes simplex infection. Syphilis is associated with rhinitis and osteochondritis. Acute neonatal viral, bacterial, or fungal infections could mimic CCMV; as well as inborn errors of metabolism, such as galactosemia and tyrosinemia. A positive newborn metabolic screen would be the expectation, with inborn errors of metabolism. History and physical examination, bacterial, or fungal cultures would help distinguish other infections.

Prognosis

Prognosis is poor. Symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus leads to long term sequelae including sensorineural hearing loss, mental and developmental disabilities, and impaired vision. Around 10% of symptomatic newborns will die in the neonatal period, a number that may be low. Asymptomatic babies are not spared long-term sequelae, with 10 to 12% developing hearing loss and a smaller percentage of developing neuromotor disabilities and vision problems.[21] Infants of mothers who acquired primary CMV in pregnancy or who are symptomatic with microcephaly, intracranial calcifications or chorioretinitis have the worst prognosis.[37]

Complications

Complications occur more commonly in symptomatic CMV infection. These include:

- Sensorineural hearing loss: Most common complication and it affects both symptomatic and asymptomatic neonates

- Neurodevelopmental delays: including motor deficits such as cerebral palsy, and cognitive deficits

- Ophthalmological deficits: ranging from the clinical finding of chorioretinitis to optic atrophy that may be associated with vision loss

- Seizures

- Death

Deterrence and Patient Education

The greatest risk to pregnant women is exposure to urine or saliva of young children. Preventive steps that can reduce primary infection in pregnancy include education of pregnant women to increase awareness of CMV. Specific strategies that can be employed to decrease transmission include thorough hand washing after handling potentially infected articles, e.g., soiled diapers and toys, and limited intimate contact with children less than 6 years of age (such as kissing on the mouth or cheek, bed sharing, and wiping drool). Pregnant women should be counseled not to share utensils with their children or put a child’s pacifier in their mouth.[7][38][39] Childcare workers who plan to become pregnant may need to inform their employers so that the risk can be decreased as much as possible.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The primary care provider, nurse practitioner, obstetrician, infectious disease specialty trained nurse, and the pharmacist should operate in an interprofessional health team working with each other to educate the patient on CMV prevention, particularly in places where women are most at risk. Such facilities include obstetrics offices and childcare centers. Confirmed prenatal diagnosis or high suspicion of disease without confirmation should be communicated to the newborn medical team; to ensure neonatal testing, treatment if indicated, and appropriate follow up. Early diagnosis ensures access to treatment and early intervention services.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

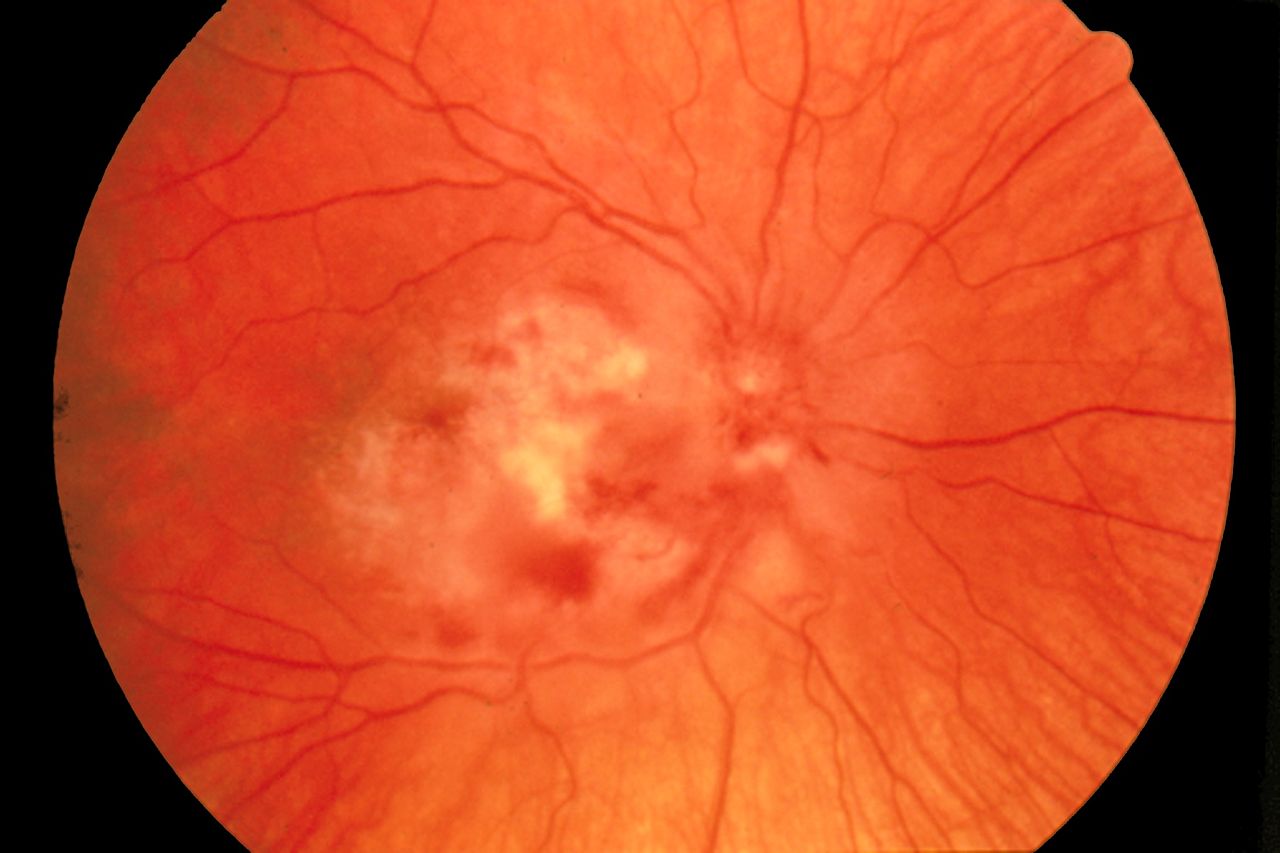

Cytomegalovirus Retinitis. The image depicts a view of a fundus affected by cytomegalovirus retinitis.

National Eye Institute, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

References

Lazzarotto T, Guerra B, Gabrielli L, Lanari M, Landini MP. Update on the prevention, diagnosis and management of cytomegalovirus infection during pregnancy. Clinical microbiology and infection : the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2011 Sep:17(9):1285-93. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03564.x. Epub 2011 Jun 1 [PubMed PMID: 21631642]

Picone O, Vauloup-Fellous C, Cordier AG, Guitton S, Senat MV, Fuchs F, Ayoubi JM, Grangeot Keros L, Benachi A. A series of 238 cytomegalovirus primary infections during pregnancy: description and outcome. Prenatal diagnosis. 2013 Aug:33(8):751-8. doi: 10.1002/pd.4118. Epub 2013 May 1 [PubMed PMID: 23553686]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBoppana SB, Pass RF, Britt WJ, Stagno S, Alford CA. Symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection: neonatal morbidity and mortality. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 1992 Feb:11(2):93-9 [PubMed PMID: 1311066]

Kylat RI,Kelly EN,Ford-Jones EL, Clinical findings and adverse outcome in neonates with symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus (SCCMV) infection. European journal of pediatrics. 2006 Nov; [PubMed PMID: 16835757]

Lanzieri TM, Leung J, Caviness AC, Chung W, Flores M, Blum P, Bialek SR, Miller JA, Vinson SS, Turcich MR, Voigt RG, Demmler-Harrison G. Long-term outcomes of children with symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus disease. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association. 2017 Jul:37(7):875-880. doi: 10.1038/jp.2017.41. Epub 2017 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 28383538]

Jeon J, Victor M, Adler SP, Arwady A, Demmler G, Fowler K, Goldfarb J, Keyserling H, Massoudi M, Richards K, Staras SA, Cannon MJ. Knowledge and awareness of congenital cytomegalovirus among women. Infectious diseases in obstetrics and gynecology. 2006:2006():80383 [PubMed PMID: 17485810]

Cannon MJ, Westbrook K, Levis D, Schleiss MR, Thackeray R, Pass RF. Awareness of and behaviors related to child-to-mother transmission of cytomegalovirus. Preventive medicine. 2012 May:54(5):351-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.03.009. Epub 2012 Mar 21 [PubMed PMID: 22465669]

Revello MG, Gerna G. Diagnosis and management of human cytomegalovirus infection in the mother, fetus, and newborn infant. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2002 Oct:15(4):680-715 [PubMed PMID: 12364375]

Pass RF. Cytomegalovirus infection. Pediatrics in review. 2002 May:23(5):163-70 [PubMed PMID: 11986492]

Kenneson A, Cannon MJ. Review and meta-analysis of the epidemiology of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Reviews in medical virology. 2007 Jul-Aug:17(4):253-76 [PubMed PMID: 17579921]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWang C, Zhang X, Bialek S, Cannon MJ. Attribution of congenital cytomegalovirus infection to primary versus non-primary maternal infection. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2011 Jan 15:52(2):e11-3. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq085. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21288834]

Bristow BN, O'Keefe KA, Shafir SC, Sorvillo FJ. Congenital cytomegalovirus mortality in the United States, 1990-2006. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2011 Apr 26:5(4):e1140. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001140. Epub 2011 Apr 26 [PubMed PMID: 21541359]

Adler SP, Nigro G, Pereira L. Recent advances in the prevention and treatment of congenital cytomegalovirus infections. Seminars in perinatology. 2007 Feb:31(1):10-8 [PubMed PMID: 17317422]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBodéus M, Kabamba-Mukadi B, Zech F, Hubinont C, Bernard P, Goubau P. Human cytomegalovirus in utero transmission: follow-up of 524 maternal seroconversions. Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 2010 Feb:47(2):201-2. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.11.009. Epub 2009 Dec 16 [PubMed PMID: 20006542]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEnders G, Daiminger A, Bäder U, Exler S, Enders M. Intrauterine transmission and clinical outcome of 248 pregnancies with primary cytomegalovirus infection in relation to gestational age. Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 2011 Nov:52(3):244-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.07.005. Epub 2011 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 21820954]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePass RF,Fowler KB,Boppana SB,Britt WJ,Stagno S, Congenital cytomegalovirus infection following first trimester maternal infection: symptoms at birth and outcome. Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 2006 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 16368262]

Revello MG, Zavattoni M, Furione M, Lilleri D, Gorini G, Gerna G. Diagnosis and outcome of preconceptional and periconceptional primary human cytomegalovirus infections. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2002 Aug 15:186(4):553-7 [PubMed PMID: 12195384]

Yinon Y, Farine D, Yudin MH. Screening, diagnosis, and management of cytomegalovirus infection in pregnancy. Obstetrical & gynecological survey. 2010 Nov:65(11):736-43. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e31821102b4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21375790]

Manicklal S, Emery VC, Lazzarotto T, Boppana SB, Gupta RK. The "silent" global burden of congenital cytomegalovirus. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2013 Jan:26(1):86-102. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00062-12. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23297260]

de Vries LS, Gunardi H, Barth PG, Bok LA, Verboon-Maciolek MA, Groenendaal F. The spectrum of cranial ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities in congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Neuropediatrics. 2004 Apr:35(2):113-9 [PubMed PMID: 15127310]

Dollard SC, Grosse SD, Ross DS. New estimates of the prevalence of neurological and sensory sequelae and mortality associated with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Reviews in medical virology. 2007 Sep-Oct:17(5):355-63 [PubMed PMID: 17542052]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBoppana SB, Ross SA, Fowler KB. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection: clinical outcome. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2013 Dec:57 Suppl 4(Suppl 4):S178-81. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit629. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24257422]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLa Torre R, Nigro G, Mazzocco M, Best AM, Adler SP. Placental enlargement in women with primary maternal cytomegalovirus infection is associated with fetal and neonatal disease. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2006 Oct 15:43(8):994-1000 [PubMed PMID: 16983610]

Dreher AM, Arora N, Fowler KB, Novak Z, Britt WJ, Boppana SB, Ross SA. Spectrum of disease and outcome in children with symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection. The Journal of pediatrics. 2014 Apr:164(4):855-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.12.007. Epub 2014 Jan 14 [PubMed PMID: 24433826]

Schleiss MR. Congenital cytomegalovirus: Impact on child health. Contemporary pediatrics. 2018 Jul:35(7):16-24 [PubMed PMID: 30740598]

Johnson J, Anderson B, Pass RF. Prevention of maternal and congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 2012 Jun:55(2):521-30. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3182510b7b. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22510635]

Rawlinson WD, Boppana SB, Fowler KB, Kimberlin DW, Lazzarotto T, Alain S, Daly K, Doutré S, Gibson L, Giles ML, Greenlee J, Hamilton ST, Harrison GJ, Hui L, Jones CA, Palasanthiran P, Schleiss MR, Shand AW, van Zuylen WJ. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection in pregnancy and the neonate: consensus recommendations for prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. The Lancet. Infectious diseases. 2017 Jun:17(6):e177-e188. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30143-3. Epub 2017 Mar 11 [PubMed PMID: 28291720]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLiesnard C,Donner C,Brancart F,Gosselin F,Delforge ML,Rodesch F, Prenatal diagnosis of congenital cytomegalovirus infection: prospective study of 237 pregnancies at risk. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2000 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 10831985]

Guerra B, Simonazzi G, Puccetti C, Lanari M, Farina A, Lazzarotto T, Rizzo N. Ultrasound prediction of symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2008 Apr:198(4):380.e1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.09.052. Epub 2008 Jan 14 [PubMed PMID: 18191802]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAzam AZ, Vial Y, Fawer CL, Zufferey J, Hohlfeld P. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2001 Mar:97(3):443-8 [PubMed PMID: 11239654]

Guerra B, Lazzarotto T, Quarta S, Lanari M, Bovicelli L, Nicolosi A, Landini MP. Prenatal diagnosis of symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2000 Aug:183(2):476-82 [PubMed PMID: 10942490]

Naing ZW, Scott GM, Shand A, Hamilton ST, van Zuylen WJ, Basha J, Hall B, Craig ME, Rawlinson WD. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection in pregnancy: a review of prevalence, clinical features, diagnosis and prevention. The Australian & New Zealand journal of obstetrics & gynaecology. 2016 Feb:56(1):9-18. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12408. Epub 2015 Sep 22 [PubMed PMID: 26391432]

Nigro G, Adler SP, La Torre R, Best AM, Congenital Cytomegalovirus Collaborating Group. Passive immunization during pregnancy for congenital cytomegalovirus infection. The New England journal of medicine. 2005 Sep 29:353(13):1350-62 [PubMed PMID: 16192480]

Revello MG, Lazzarotto T, Guerra B, Spinillo A, Ferrazzi E, Kustermann A, Guaschino S, Vergani P, Todros T, Frusca T, Arossa A, Furione M, Rognoni V, Rizzo N, Gabrielli L, Klersy C, Gerna G, CHIP Study Group. A randomized trial of hyperimmune globulin to prevent congenital cytomegalovirus. The New England journal of medicine. 2014 Apr 3:370(14):1316-26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310214. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24693891]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRawlinson WD, Hamilton ST, van Zuylen WJ. Update on treatment of cytomegalovirus infection in pregnancy and of the newborn with congenital cytomegalovirus. Current opinion in infectious diseases. 2016 Dec:29(6):615-624 [PubMed PMID: 27607910]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLackner A, Acham A, Alborno T, Moser M, Engele H, Raggam RB, Halwachs-Baumann G, Kapitan M, Walch C. Effect on hearing of ganciclovir therapy for asymptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection: four to 10 year follow up. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2009 Apr:123(4):391-6. doi: 10.1017/S0022215108003162. Epub 2008 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 18588736]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLeung AK, Sauve RS, Davies HD. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2003 Mar:95(3):213-8 [PubMed PMID: 12749681]

Cannon MJ, Davis KF. Washing our hands of the congenital cytomegalovirus disease epidemic. BMC public health. 2005 Jun 20:5():70 [PubMed PMID: 15967030]

Adler SP, Finney JW, Manganello AM, Best AM. Prevention of child-to-mother transmission of cytomegalovirus among pregnant women. The Journal of pediatrics. 2004 Oct:145(4):485-91 [PubMed PMID: 15480372]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence