Introduction

The airway, or respiratory tract, describes the organs of the respiratory tract that allow airflow during ventilation. [1][2][3]They reach from the nares and buccal opening to the blind end of the alveolar sacs. They are subdivided into different regions with various organs and tissues to perform specific functions. The airway can be subdivided into the upper and lower airway, each of which has numerous subdivisions as follows.

Upper Airway

The pharynx is the mucous membrane-lined portion of the airway between the base of the skull and the esophagus and is subdivided as follows:

- Nasopharynx, also known as the rhino-pharynx, post-nasal space, is the muscular tube from the nares, including the posterior nasal cavity, divide from the oropharynx by the palate and lining the skull base superiorly

- The oro-pharynx connects the naso and hypopharynx. It is the region between the palate and the hyoid bone, anteriorly divided from the oral cavity by the tonsillar arch

- The hypopharynx connects the oropharynx to the esophagus and the larynx, the region of pharynx below the hyoid bone.

The larynx is the portion of the airway between the pharynx and the trachea, contains the organs for the production of speech. Formed of a cartilaginous skeleton of nine cartilages, it includes the important organs of the epiglottis and the vocal folds (vocal cords) which are the opening to the glottis.

Lower Airway

The trachea is a ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium-lined tubular structure supported by C-shaped rings of hyaline cartilage. The flat open surface of these C rings opposes the esophagus to allow its expansion during swallowing. The trachea bifurcates and therefore terminates, superior to the heart at the level of the sternal angle.

The bronchi, the main bifurcation of the trachea, are similar in structure but have complete circular cartilage rings.

- Main bronchi: There are two supplying ventilation to each lung. The right main bronchus has a larger diameter and is aligned more vertically than the left

- Lobar bronchi: Two on the left and three on the right supply each of the main lobes of the lung

- Segmental bronchi supply individual bronchopulmonary segments of the lungs.

Bronchioles lack supporting cartilage skeletons and have a diameter of around 1 mm. They are initially ciliated and graduate to the simple columnar epithelium and their lining cells no longer contain mucous producing cells.

- Conducting bronchioles conduct airflow but do not contain any mucous glands or seromucous glands

- Terminal bronchioles are the last division of the airway without respiratory surfaces

- Respiratory bronchioles contain occasional alveoli and have surface surfactant-producing They each give rise to between two and 11 alveolar ducts.

Alveolar is the final portion of the airway and is lined with a single-cell layer of pneumocytes and in proximity to capillaries. They contain surfactant producing type II pneumocytes and Clara cells.

- Alveolar ducts are tubular portions with respiratory surfaces from which the alveolar sacs bud.

- Alveolar sacs are the blind-ended spaces from which the alveoli clusters are formed and to where they connect. These are connected by pores which allow air pressure to equalize between them. Together, with the capillaries, they form the air-blood barrier.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Airways allow airflow in ventilation from the external environment to the respiratory surfaces where gas exchange for respiratory processes can occur.[4][5]

To allow this and to maintain homeostasis and adequate protection from the external environment they must also perform other barrier functions.

- Moisture barrier is the mucous lining of the airway that provides a barrier to prevent loss of excessive moisture during ventilation by increasing the humidity of the air in the upper airway

- Temperature barrier is relative to body temperature as the external environment is nearly always colder, and the increased vasculature and structures such as nasal turbinates warm air as it enters the airways

- A barrier to infection as the airways are lined with a rich lymphatic system including mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) that prevents early access to any invading pathogens. Macrophages also patrol the respiratory surfaces providing an important component of the “air-blood barrier."

Embryology

The upper airways develop from the pharyngeal arches as part of the embryological development of the head and neck structures.

At around four weeks, the larynx and lower airways develop from the longitudinal laryngotracheal groove which forms a medial, groove-like structure becoming a tubular, blind-ended structure called the laryngotracheal diverticulum. This eventually separates from the developing foregut by the formation of the tracheo-oesophageal folds.

The laryngeal cartilages and musculature develop from the four and six pharyngeal arches, and the glottic opening forms connecting this region to the trachea.

The trachea forms from the extension of the laryngotracheal diverticulum, and it is lined with endodermal tissue which forms the specialized respiratory linings and mesodermal structures that form the cartilage and smooth muscle walls.

As development continues, the laryngotracheal diverticulum continues to branch and bud and forms the bronchi and branching bronchioles.

From 16 weeks onward, respiratory surfaces begin to form, and the maturation of the lungs develops with alveolar sacs forming and pneumocyte development forming the respiratory membrane.

The formation of the alveoli and the respiratory membrane is not complete until after birth, and alveolar formation continues until the age of eight.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The upper airways receive blood supply from various branches of the external carotid artery and drain into the internal jugular. The naso and oropharynx also receive blood supply from the facial artery branch of the external carotid via the tonsillar artery. The venous drainage of these structures is via the pharyngeal plexus into the internal jugular vein. The lymphatic drainage is through various lymphatic plexuses of the neck surrounding the internal jugular vessels.

The lower airways receive blood flow from two sources: the pulmonary circulation and the bronchial circulation.

The pulmonary circulation provides blood from the heart for oxygenation through the right and left pulmonary arteries which follow a branching structure similar to that of the airways themselves. This blood returns as oxygenated blood through the pulmonary veins which follow an independently branching structure to return to the right ventricle.

Bronchial circulation provides oxygenated blood to the airway structures themselves. These arteries arise independently from the systemic circulation. The two left bronchial arteries emerge from the thoracic aorta; whereas, the right bronchial artery arises either from one of the superior posterior intercostal arteries or a common trunk with the left superior bronchial artery. These provide nutrition and oxygen to tissues as far as the end of the conducting airways where they anastomose with the pulmonary circulation.

The bronchial veins are only present near the lung hilum which drain blood from the trachea, and bronchi drain into the azygos vein on the right and either the accessory hemiazygos veins or the intercostal vessels on the left. Pulmonary veins drain the more distal circulation where a small amount of deoxygenated blood makes a minimal impact on the saturation of the returning blood.

Lymphatic drainage of the lower airways is through the deep lymphatic plexuses of the pulmonary lymphatic plexuses. These drain to the superior and inferior tracheobronchial lymph nodes bilaterally and then to the right and left ducts connecting to the venous angles, usually directly but on the left, this may converge with the thoracic duct first.

Paratracheal nodes drain lymph from the trachea directly into the right and left lymphatic ducts.

Nerves

Innervation of the pharynx is via cranial nerves VII, IX, X, and XII. The larynx is supplied by the vagus (cranial nerve X) by the superior laryngeal branch directly and the clinically important recurrent laryngeal branch.

The lower airways receive parasympathetic fibers from the vagus, some of which are afferent sensory nerves that transmit cough sensations from specialized J receptors in the mucosa as well as stretch receptors from the bronchial muscles and inter-alveolar connective tissues. The efferent fibers of the vagus cause broncho-constriction and secretion from the glandular tissues in the airways. The efferent sympathetic fibers cause bronchodilation by inhibiting the activity of the smooth muscles of the airways.

Muscles

The muscles of the pharynx and larynx provide the structure of the upper airways and form from striated muscles under visceral and somatic control. They relate to the action of swallowing.

The lower airways have a layer of smooth muscle within their walls. It is present along all of the conducting airways and allows for visceral control of bronchoconstriction

Physiologic Variants

The most common anatomic variation is an abnormal tracheo-oesophageal fistula. This variation occurs most commonly in males and often is associated with oesophageal atresia. It occurs with the incomplete fusion of the tracheo-oesophageal folds which would divide the developing foregut into respiratory and oesophageal portions.

Surgical Considerations

The anatomy of the airway is important in all trauma and emergency surgical scenarios. As in any emergency assessment, a practitioner should know it is most important to consider and evaluate the patent airway.[6][7][4][8]

The upper airways can be controlled using airway devices and bypassed using endotracheal intubation. If this is not possible, emergent surgical access to the airway is imperative and is performed through an emergency cricothyroidotomy.

Airway assessment is relevant to many common surgeries:

- Tonsils causing any airway compromise indicate surgical removal.

- Any neck trauma external to the airway can cause an external compression which can compromise the airway. This compromise is of particular importance in trauma and operations on surrounding structures such as thyroidectomy.

Clinical Significance

The importance of the upper airway assessment is paramount in both emergency and anesthetic scenarios.[9]

The upper airway assessment can be performed and enhanced by the following assessment tools:

- The Malampati score which describes the visible airway

- The "3, 3, 2" rule in which three estimated measurements of the inter incisor distance

- The hyoid-mental distance, hyoid-thyroid cartilage distance is measured, and if these are shortened, it implies a difficult airway.

The cricoid cartilage is important both as a clinical landmark and also as the only complete cartilage ring within the upper airway used during cricoid pressure maneuvers.

The narrowest portion of the upper airway is the cricoid cartilage in children; therefore, cricothyroidotomy is not recommended in children younger than the age of eight. As children grow and mature, the glottic opening becomes the most narrow point in the airway, and therefore, the most likely point of obstruction and allows bypass by the insertion of a cricothyroidotomy airway.

The trachea is the most anterior structure of the neck except for where the thyroid covers it. This means that it can be accessed to provide an airway in both emergencies (cricothyroidotomy) and elective procedures (tracheotomy).

The trachea should align with the sternal notch. If this alignment deviates, it can indicate a lung or mediastinal pathology.

The right, main bronchus is shorter, wider, and vertically aligned, and this means it is the most common site for aspiration, both in a foreign body aspiration and during the occurrence of an aspiration pneumonitis causing right lower lobe consolidation.

In clinical assessment of the lower airways, through auscultation and by the presence of "wheezing" as turbulent airflow generates a musical noise, airway narrowing through edema or bronchoconstriction can be detected.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

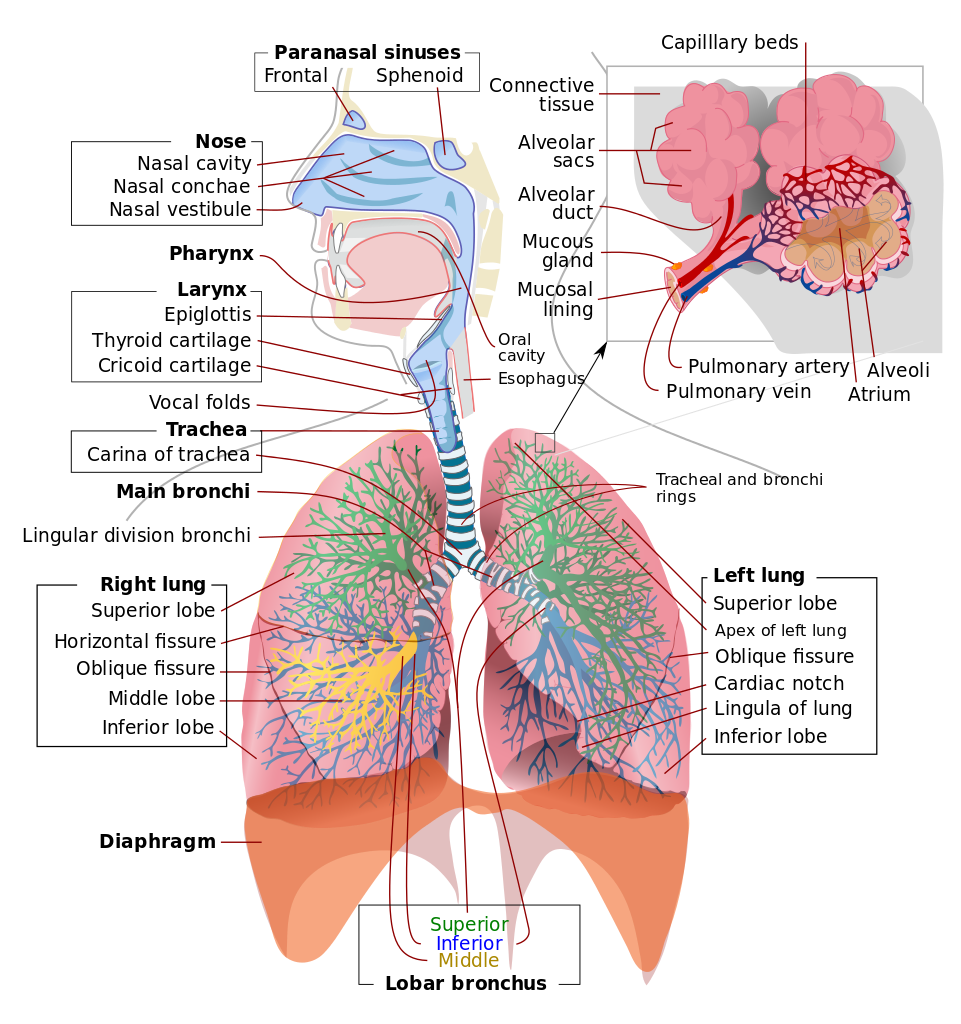

Respiratory System. This illustration shows the upper respiratory tract, consisting of the paranasal sinuses, nose, nasal cavity, nasal conchae, nasal vestibule, pharynx, larynx, epiglottis, and vocal folds. Of the paranasal sinuses, the frontal and sphenoid sinuses are included. The illustration also shows the lower respiratory region, comprised of the thyroid cartilage, cricoid cartilage, trachea and tracheal carina, main bronchi, tracheal and bronchial rings, lobar bronchi (superior, middle, and inferior), and right and left lungs. The insert shows alveolar anatomy, which includes the alveolar sacs, alveolar duct, mucous gland, mucosal lining, pulmonary artery and vein, capillary beds, and alveolar atrium.

Contributed by Wikimedia Commons, LadyofHats (Public Domain)

References

Wani TM, Bissonnette B, Engelhardt T, Buchh B, Arnous H, AlGhamdi F, Tobias JD. The pediatric airway: Historical concepts, new findings, and what matters. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2019 Jun:121():29-33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.02.041. Epub 2019 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 30861424]

Benner A, Sharma P, Sharma S. Anatomy, Head and Neck: Cervical, Respiratory, Larynx, and Cricoarytenoid. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30855891]

Saran M, Georgakopoulos B, Bordoni B. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Larynx Vocal Cords. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30570963]

Clark CM, Kugler K, Carr MM. Common causes of congenital stridor in infants. JAAPA : official journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants. 2018 Nov:31(11):36-40. doi: 10.1097/01.JAA.0000546480.64441.af. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30358678]

De Rose V, Molloy K, Gohy S, Pilette C, Greene CM. Airway Epithelium Dysfunction in Cystic Fibrosis and COPD. Mediators of inflammation. 2018:2018():1309746. doi: 10.1155/2018/1309746. Epub 2018 Apr 8 [PubMed PMID: 29849481]

Olszewska E, Woodson BT. Palatal anatomy for sleep apnea surgery. Laryngoscope investigative otolaryngology. 2019 Feb:4(1):181-187. doi: 10.1002/lio2.238. Epub 2019 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 30828637]

Estime SR, Kuza CM. Trauma Airway Management: Induction Agents, Rapid Versus Slower Sequence Intubations, and Special Considerations. Anesthesiology clinics. 2019 Mar:37(1):33-50. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2018.09.002. Epub 2018 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 30711232]

Thomson NC. Challenges in the management of asthma associated with smoking-induced airway diseases. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 2018 Oct:19(14):1565-1579. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2018.1515912. Epub 2018 Sep 8 [PubMed PMID: 30196731]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDetsky ME, Jivraj N, Adhikari NK, Friedrich JO, Pinto R, Simel DL, Wijeysundera DN, Scales DC. Will This Patient Be Difficult to Intubate?: The Rational Clinical Examination Systematic Review. JAMA. 2019 Feb 5:321(5):493-503. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.21413. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30721300]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence