Introduction

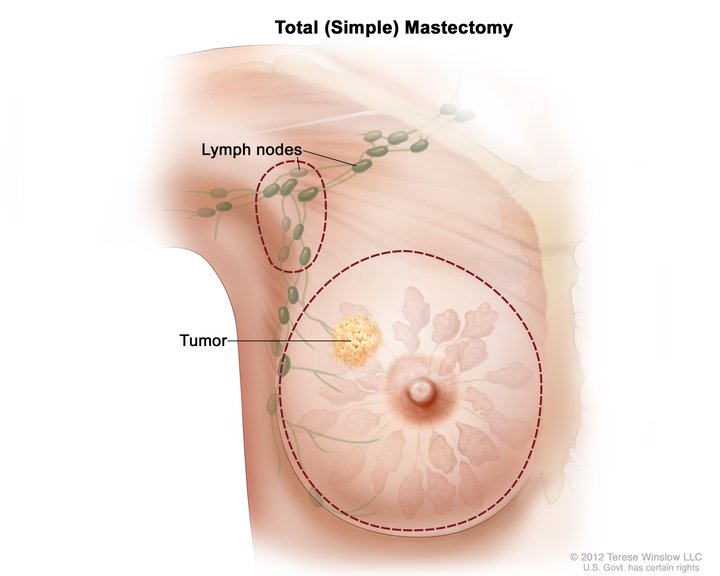

A mastectomy is a surgical procedure to remove all breast tissue. Various types of mastectomy exist based on the indications for surgery. A simple mastectomy, which is the most commonly performed procedure, involves removing all the breast tissue and the overlying skin and nipple-areolar complex (see Image. Total Simple Mastectomy).[1] Variations of the simple mastectomy include a skin-sparing mastectomy with a significant amount of the skin preserved for reconstruction and a nipple-sparing mastectomy where the nipple-areolar complex and most of the skin overlying the breast are preserved. A modified radical mastectomy combines a simple mastectomy with an axillary lymph node dissection.

In contrast, a radical mastectomy, which is mostly of historical interest, involves the simultaneous removal of the chest wall muscles.[2] Historically, mastectomy was the procedure of choice for breast cancer. With our improved understanding of breast cancer biology, advances in chemotherapy and radiation, and the knowledge that breast cancers are systemic diseases, more limited surgical procedures, such as partial mastectomies or lumpectomies, are now far more commonly performed. Mastectomy remains an essential adjunct to therapy and is still indicated in specific benign and malignant breast lesions. This article focuses on the anatomy of the breast, indications for mastectomy, and the conduct of various types of simple mastectomy.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The adult female breast is located on the anterior superior thoracic wall, from the second rib superiorly to the inframammary fold inferiorly and extending from the sternal border medially to the midaxillary line laterally. Most of the breast tissue overlies the pectoralis major muscle, while the serratus anterior and upper portion of the external oblique muscles comprise the remaining posterior boundary. For anatomical reference, the breast is conventionally divided into 4 quadrants centered on the nipple. The upper outer quadrant contains the highest density of glandular tissue, with some extending into the axilla as the axillary tail of Spence. This axillary extension should be excised along with other breast tissue during mastectomy procedures.

The suspensory (Cooper) ligaments anchor the breast to the anterior chest wall.[3] These connective tissue bands help maintain breast shape and support. The glandular tissue responsible for lactation comprises 15 to 20 lobules. Each lobule drains through lactiferous ducts that converge to empty at the nipple. Additionally, the breast contains variable amounts of fatty and fibrous tissue, influenced by age, reproductive status, genetics, and comorbidities.

The blood supply to the breast is derived from several sources. Medially, the internal mammary artery provides 2 to 4 anterior intercostal perforating arteries that supply the breast as medial mammary branches. Laterally, blood supply arises from the lateral branches of the posterior intercostal arteries and branches of the axillary artery, including the lateral thoracic artery and pectoral branches of the thoracoacromial artery. These vessels wrap around the superior and lateral borders of the pectoralis major to reach the breast tissue.[4]

Venous drainage mirrors the arterial supply, with primary drainage directed toward the axilla. The main venous pathways include perforating branches of the internal thoracic vein, tributaries of the axillary vein, and perforating branches of the posterior intercostal veins. Understanding venous drainage is crucial, as lymphatic channels often parallel the vascular supply, forming a potential route for cancer metastasis through lymphatic and venous channels.

Lymphatic drainage of the breast predominantly flows to the axillary nodes approximately 95% of the time. Additional lymphatic drainage pathways include the internal mammary chain, lateral and medial intramammary regions, the interpectoral region, and the subclavicular lymph node basin.[5]

The primary nerves at risk during mastectomy are the medial and lateral pectoral nerves. The medial pectoral nerve originates from the medial cord of the brachial plexus (C8-T1) and, despite its name, runs laterally to innervate the lower half of both the pectoralis major and pectoralis minor muscles. The lateral pectoral nerve, arising from the lateral cord of the brachial plexus (C5-C6), runs more medially and supplies the pectoralis major. Injury to either of these nerves can lead to weakness and atrophy of the pectoralis muscles, affecting shoulder strength and chest contour.

Indications

The indications for mastectomy and modified radical mastectomy are nuanced, constantly evolving, and not absolute.[6][7][8] Simple mastectomy is indicated for most patients in whom breast cancer conservation therapy is contraindicated or is a patient preference. The indications include:

- Multifocal ductal carcinoma in situ or invasive breast cancer

- History of prior radiation to the breast or chest wall

- Prophylactic mastectomy for breast cancer risk reduction

- Involvement of the skin or chest wall

- Large tumor-to-breast ratio, which precludes breast conservation

- Persistently positive margins despite multiple resections

- Patient preference to avoid radiation

- Palliation in locally advanced breast cancer

- As part of managing gender dysphoria.[9]

Nipple-sparing mastectomy may be an appropriate choice in patients with cancers that do not involve the nipple-areola complex. This procedure should be avoided in patients with Paget disease of the nipple, gross involvement of the nipple-areolar complex, inflammatory breast cancer, and certain anatomic features such as severely ptotic breasts.[10][11]

Modified radical mastectomy is indicated for breast cancer in the following situations:

- Anaplastic breast cancer

- Clinically positive lymph nodes

- More than 3 positive sentinel lymph nodes

- Axillary recurrent tumors

- Contraindications to radiation

- Unsuccessful sentinel lymph node biopsy.[8]

Contraindications

Mastectomy is contraindicated in patients who cannot undergo general anesthesia. This procedure is relatively contraindicated in patients with metastatic disease, as mastectomy is unlikely to alter the overall outcome in these patients. In select patients with severe, symptomatic, locally advanced disease, a palliative mastectomy may be appropriate, especially in settings where radiation is not readily available.

Equipment

No special surgical equipment is required for mastectomy. Lighted retractors are helpful in nipple-sparing mastectomies.

Personnel

Breast cancer care is complex and involves a comprehensive interprofessional care team. Once the appropriate operation is decided, the surgical team consists of the surgeon, an assistant, perioperative staff, anesthesia clinicians, and surgical technologists. If reconstruction is planned, this is typically performed by a plastic surgeon and requires the appropriate implants.

Preparation

Diagnostic imaging and histopathology should be thoroughly reviewed before surgery. Preoperative antibiotics must be administered within 30 minutes of the incision. General anesthesia is usually used for mastectomy, with regional anesthesia acting as an adjunct. Regional anesthesia reduces postoperative pain and may reduce chronic pain. Thoracic epidural, paravertebral, and pectoral blocks may be used.[12]

Before the procedure begins, the patient is placed supine with the arms out. If an axillary lymph node dissection is performed, the involved extremity should be prepped and draped to allow the arm to be moved and axillary access.

Technique or Treatment

Several approaches exist for performing a mastectomy. In a modified radical mastectomy, a simple mastectomy is combined with an axillary lymphadenectomy. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Axillary Lymphadenectomy," for more information on this procedure.

Incision

In general, the appropriate incision is created and deepened through the epidermis and dermis. Electrocautery through the deeper dermal layers minimizes bleeding. The following incisions may be employed as dictated by the mastectomy approach:

- Simple mastectomy: Typically, an elliptical skin incision that includes the nipple-areolar complex (NAC) is performed. The incision is oriented diagonally, with the lateral aspect positioned superiorly near the axilla, facilitating concealment under clothing. The ellipse's width varies depending on breast size, ensuring closure without excessive laxity or tension (see Image. Total Simple Mastectomy). The initial ellipse is often conservative, with final adjustments made post-breast removal.

- Skin-sparing mastectomy: A similar elliptical incision includes the NAC but preserves much of the breast skin, enabling immediate breast reconstruction.[1]

- Nipple-sparing mastectomy: The NAC is preserved. Incisions vary, with the inframammary fold incision being the most common, followed by lateral, vertical radial, and periareolar options.[13]

- Modified radical mastectomy: Uses an incision similar to the simple mastectomy but may extend into the axilla for simultaneous axillary lymphadenectomy (see Image. Modified Radical Mastectomy).

Raising Superior and Inferior Flaps

The skin is elevated straight up with skin hooks or sharp grasping retractors, while counter-tension is applied to the breast tissue. The breast tissue is dissected from the overlying skin and subcutaneous tissue to create superior and inferior skin flaps.[14] This plane is typically avascular. Sharp dissection or energy devices can be used. Techniques such as tumescence are sometimes used to aid dissection. Dissection should avoid creating excessively thin flaps to prevent "buttonholing" or overly thick flaps that risk leaving residual breast tissue. The superior flap extends to the second rib and down to the pectoralis major fascia. Laterally, the flap reaches the anterior border of the latissimus dorsi, medially to the lateral sternal border, and inferiorly to the inframammary fold, which generally has less breast tissue.

Dissection of Breast Tissue from the Chest Wall

The breast tissue is elevated from the pectoralis major muscle, typically proceeding from medial to lateral and superior to inferior. Medially, perforating branches of the internal mammary artery should be identified, coagulated, or ligated to avoid retraction into the pectoralis major if transected. The fascia overlying the pectoralis major is included with the specimen. Once removed, the specimen is oriented and marked with sutures. The wound cavity is thoroughly irrigated, and hemostasis is confirmed.

Incision Closure

Closure depends on the mastectomy type. For a simple mastectomy, skin edges are approximated without excessive tension while avoiding laxity. The superior and inferior flaps should lie flush against the chest wall to prevent seroma formation; trimming excess skin and soft tissue may be necessary. Quilting sutures that anchor the flaps to the underlying tissue may be used to reduce dead space and seroma formation. Closed-suction drains are usually placed laterally. Deep dermal layers are closed with interrupted sutures, and the skin is approximated with subcuticular sutures or staples.

For skin-sparing or nipple-sparing mastectomy, immediate reconstruction with a temporary implant is typically performed, though details are outside the scope of this activity. In a modified radical mastectomy, the lateral incision may be extended for axillary access, or a separate incision may be created for the axillary lymphadenectomy.[15]

Postoperative Care

Patients are typically observed overnight. Restricting arm movement on the affected side for 24 to 48 hours and a compressive binder over the operative site reduces edema, seroma formation, and pain. Multimodal analgesia is recommended to minimize opioid use. Antispasmodic agents and muscle relaxants are beneficial for pain control, particularly when tissue expanders are placed. Drains are generally removed when output is less than 30 mL over 24 hours.

Complications

Mastectomies are well-tolerated procedures with low morbidity and mortality. However, several complications are associated with the procedure.

Seroma Formation

A seroma is a fluid accumulation in the dead space created in the wound bed following mastectomy, typically composed of transudate and lymphatic fluid. Nearly all mastectomies result in some degree of seroma formation, though the incidence of clinically significant seromas varies considerably. Research has examined factors influencing seroma formation and interventions to reduce its occurrence. Electrocautery and early arm mobilization are associated with a higher risk of seromas. Measures to mitigate seroma formation include using fibrin sealants, suction drains, compressive bandages, and sutures to obliterate dead space; the evidence supporting these methods remains inconclusive. While most seromas are self-limiting and resorb over time, they can predispose patients to complications, including infection, discomfort, and skin flap necrosis. Larger, symptomatic seromas may necessitate percutaneous drainage.[15][16]

Wound Infection

The reported surgical site infection rates vary widely from 5% to 8%. Most wound infections can be treated with oral antibiotics. Deeper infections and infected seromas or hematomas may require percutaneous or operative drainage. Appropriate preoperative antibiotics and sterile techniques are vital in preventing surgical site infections.[15][17][18]

Bleeding and Hematoma Formation

Immediate postoperative bleeding may occur in up to 5% of patients, with a reported rate of bleeding requiring a return to the operating room of roughly 2%. Most bleeding occurs within 24 hours after surgery. More minor hematomas may be controlled with firm pressure, but ongoing bleeding or larger hematomas require evacuation and hemostasis in the operating room. Often, no active bleeding is identified at the time of reoperation.[15] Meticulous hemostasis during surgery and using energy devices and topical hemostatic agents may help reduce bleeding.

Flap Necrosis

Flap necrosis is unusual following simple radical mastectomies. This complication is most commonly seen in skin-sparing or nipple-sparing mastectomies, where an implant is placed during surgery. Flap necrosis is caused by ischemia to the flap and can often be managed with watchful waiting. Extensive flap necrosis may require an excision of the flap and conversion of less extensive procedures to a simple mastectomy.[15][19] Necrosis of the nipple-areolar complex may be seen with nipple-sparing mastectomy.

Chronic Pain

Pain persisting for more than 2 months after surgery in the absence of any clear etiology is referred to as persistent postsurgical pain. The pain is often described as similar to neuropathic pain and is more common with more extensive resections. Using regional anesthesia preoperatively may reduce the incidence. Management includes physiotherapy, behavioral therapy, and medications, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants.[20]

Clinical Significance

Significant advances have been made in the management of breast cancer patients since Halsted first described the radical mastectomy in the late 1800s. A growing trend toward breast conservation has been observed, and numerous studies have evaluated the efficacy of breast-conserving surgery when compared to standard mastectomy techniques. With the addition of adjuvant therapies, including radiation and systemic treatment with chemotherapy and endocrine therapy, rates of mastectomy have declined. However, mastectomy remains an essential surgical procedure and is still relevant in several clinical scenarios. Additionally, in parts of the world that do not have ready access to radiation therapy and the latest chemotherapy, mastectomy remains the cornerstone of breast cancer management.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Managing breast cancer, particularly with procedures like mastectomy, demands a high level of skill and coordinated strategy among various healthcare professionals to ensure patient-centered care and positive outcomes. Physicians and advanced practitioners are responsible for accurately diagnosing, staging, and planning treatment, balancing the risks and benefits of mastectomy with alternative therapies. Surgeons and plastic surgeons provide technical expertise and collaborate with oncologists to plan comprehensive, individualized care. Nurses play a vital role in supporting preoperative and postoperative care, educating patients on wound care and post-mastectomy exercises, and offering emotional support. Pharmacists ensure safe, effective pain management and minimize medication-related risks, especially in complex post-surgical regimens.

Interprofessional communication is essential, with regular team meetings to discuss treatment progress, updates, and shared goals, ensuring that every patient receives cohesive care. Psychologists and survivorship care healthcare professionals support patients in processing the emotional and psychological impacts of mastectomy, offering coping strategies that enhance recovery and quality of life. Coordinating this care requires a mutual commitment to patient safety and shared decision-making, where each team member’s responsibilities align to create a supportive environment that prioritizes the patient’s physical and mental health needs throughout their breast cancer journey.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Total Simple Mastectomy. This illustration shows a scheme for removing the breast and lymph nodes in a total (simple) mastectomy. The dotted line shows where the breast incision is made. The procedure may also include axillary lymph node dissection.

National Cancer Institute, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

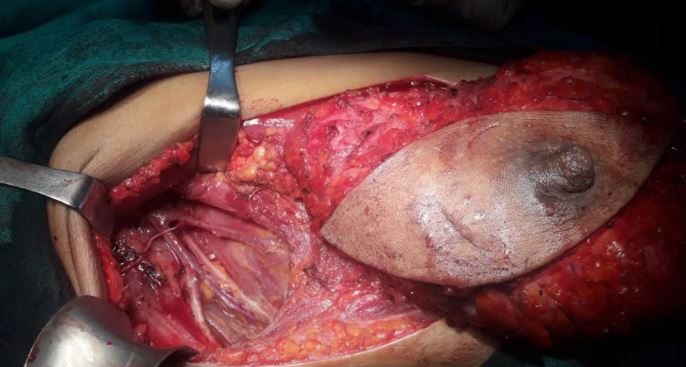

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Mota BS, Bevilacqua JLB, Barrett J, Ricci MD, Munhoz AM, Filassi JR, Baracat EC, Riera R. Skin-sparing mastectomy for the treatment of breast cancer. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2023 Mar 27:3(3):CD010993. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010993.pub2. Epub 2023 Mar 27 [PubMed PMID: 36972145]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSakorafas GH. The origins of radical mastectomy. AORN journal. 2008 Oct:88(4):605-8. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2008.06.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18928961]

Duncan AM, Al Youha S, Joukhadar N, Konder R, Stecco C, Wheelock ME. Anatomy of the Breast Fascial System: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2022 Jan 1:149(1):28-40. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000008671. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34936599]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVegas MR, Martina L, Segovia-Gonzalez M, Garcia-Garcia JF, Gonzalez-Gonzalez A, Mendieta-Baro A, Nieto-Gongora C, Benito-Duque P. Vascular anatomy of the breast and its implications in the breast-sharing reconstruction technique. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2023 Jan:76():180-188. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2022.10.021. Epub 2022 Oct 17 [PubMed PMID: 36521264]

Machado P, Liu JB, Needleman L, Lee C, Forsberg F. Anatomy Versus Physiology: Is Breast Lymphatic Drainage to the Internal Thoracic (Internal Mammary) Lymphatic System Clinically Relevant? Journal of breast cancer. 2023 Jun:26(3):286-291. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2023.26.e16. Epub 2023 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 37272244]

Cardoso MJ, de Boniface J, Dodwell D, Kaidar-Person O, Poortmans P, van Maaren MC. Which real indications remain for mastectomy? Lancet regional health. Americas. 2024 May:33():100734. doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2024.100734. Epub 2024 Apr 4 [PubMed PMID: 38590325]

Ciabattoni A, Gregucci F, De Rose F, Falivene S, Fozza A, Daidone A, Morra A, Smaniotto D, Barbara R, Lozza L, Vidali C, Borghesi S, Palumbo I, Huscher A, Perrucci E, Baldissera A, Tolento G, Rovea P, Franco P, De Santis MC, Grazia AD, Marino L, Meduri B, Cucciarelli F, Aristei C, Bertoni F, Guenzi M, Leonardi MC, Livi L, Nardone L, De Felice F, Rosetto ME, Mazzuoli L, Anselmo P, Arcidiacono F, Barbarino R, Martinetti M, Pasinetti N, Desideri I, Marazzi F, Ivaldi G, Bonzano E, Cavallari M, Cerreta V, Fusco V, Sarno L, Bonanni A, Mangiacotti MG, Prisco A, Buonfrate G, Andrulli D, Fontana A, Bagnoli R, Marinelli L, Reverberi C, Scalabrino G, Corazzi F, Doino D, Di Genesio-Pagliuca M, Lazzari M, Mascioni F, Pace MP, Mazza M, Vitucci P, Spera A, Macchia G, Boccardi M, Evangelista G, Sola B, La Porta MR, Fiorentino A, Levra NG, Ippolito E, Silipigni S, Osti MF, Mignogna M, Alessandro M, Ursini LA, Nuzzo M, Meattini I, D'Ermo G. AIRO Breast Cancer Group Best Clinical Practice 2022 Update. Tumori. 2022 Jul:108(2_suppl):1-144. doi: 10.1177/03008916221088885. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36112842]

Gradishar WJ, Moran MS, Abraham J, Abramson V, Aft R, Agnese D, Allison KH, Anderson B, Burstein HJ, Chew H, Dang C, Elias AD, Giordano SH, Goetz MP, Goldstein LJ, Hurvitz SA, Jankowitz RC, Javid SH, Krishnamurthy J, Leitch AM, Lyons J, Mortimer J, Patel SA, Pierce LJ, Rosenberger LH, Rugo HS, Schneider B, Smith ML, Soliman H, Stringer-Reasor EM, Telli ML, Wei M, Wisinski KB, Young JS, Yeung K, Dwyer MA, Kumar R. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Breast Cancer, Version 4.2023. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2023 Jun:21(6):594-608. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2023.0031. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37308117]

Miroshnychenko A, Roldan YM, Ibrahim S, Kulatunga-Moruzi C, Dahlin K, Montante S, Couban R, Guyatt G, Brignardello-Petersen R. "Mastectomy for individuals with gender dysphoria below 26 years of age: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2024 Sep 10:():. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000011734. Epub 2024 Sep 10 [PubMed PMID: 39252149]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKopkash K, Sisco M, Poli E, Seth A, Pesce C. The modern approach to the nipple-sparing mastectomy. Journal of surgical oncology. 2020 Jul:122(1):29-35. doi: 10.1002/jso.25909. Epub 2020 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 32219847]

Valero MG, Muhsen S, Moo TA, Zabor EC, Stempel M, Pusic A, Gemignani ML, Morrow M, Sacchini VS. Increase in Utilization of Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy for Breast Cancer: Indications, Complications, and Oncologic Outcomes. Annals of surgical oncology. 2020 Feb:27(2):344-351. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07948-x. Epub 2019 Dec 10 [PubMed PMID: 31823173]

Plunkett A, Scott TL, Tracy E. Regional anesthesia for breast cancer surgery: which block is best? A review of the current literature. Pain management. 2022 Nov:12(8):943-950. doi: 10.2217/pmt-2022-0048. Epub 2022 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 36177958]

Smith BL, Coopey SB. Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy. Advances in surgery. 2018 Sep:52(1):113-126. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2018.03.008. Epub 2018 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 30098607]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJones C, Lancaster R. Evolution of Operative Technique for Mastectomy. The Surgical clinics of North America. 2018 Aug:98(4):835-844. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2018.04.003. Epub 2018 May 21 [PubMed PMID: 30005777]

Colwell AS, Christensen JM. Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy and Direct-to-Implant Breast Reconstruction. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2017 Nov:140(5S Advances in Breast Reconstruction):44S-50S. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000003949. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29064921]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSpiekerman van Weezelenburg MA, Daemen JHT, van Kuijk SMJ, van Haaren ERM, Janssen A, Vissers YLJ, Beets GL, van Bastelaar J. Seroma formation after mastectomy: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of different flap fixation techniques. Journal of surgical oncology. 2024 May:129(6):1015-1024. doi: 10.1002/jso.27589. Epub 2024 Jan 21 [PubMed PMID: 38247263]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTamminen A, Koskivuo I. Preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis in mastectomy: A retrospective comparative analysis of 1413 patients with breast cancer. Scandinavian journal of surgery : SJS : official organ for the Finnish Surgical Society and the Scandinavian Surgical Society. 2022 Sep:111(3):56-64. doi: 10.1177/14574969221116940. Epub 2022 Aug 24 [PubMed PMID: 36000713]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOlsen MA, Nickel KB, Fox IK, Margenthaler JA, Ball KE, Mines D, Wallace AE, Fraser VJ. Incidence of Surgical Site Infection Following Mastectomy With and Without Immediate Reconstruction Using Private Insurer Claims Data. Infection control and hospital epidemiology. 2015 Aug:36(8):907-14. doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.108. Epub 2015 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 26036877]

Pagliara D, Schiavone L, Garganese G, Bove S, Montella RA, Costantini M, Rinaldi PM, Bottosso S, Grieco F, Rubino C, Salgarello M, Ribuffo D. Predicting Mastectomy Skin Flap Necrosis: A Systematic Review of Preoperative and Intraoperative Assessment Techniques. Clinical breast cancer. 2023 Apr:23(3):249-254. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2022.12.021. Epub 2023 Jan 4 [PubMed PMID: 36725477]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNarusawa E, Sadeghi S, Tane K, Alkhaifi M, Kikawa Y. Updates on the preventions and management of post-mastectomy pain syndrome beyond medical treatment: a comprehensive narrative review. Annals of palliative medicine. 2024 Sep:13(5):1258-1264. doi: 10.21037/apm-24-73. Epub 2024 Aug 16 [PubMed PMID: 39168643]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence