Introduction

Emphysematous pyelonephritis (EPN) is a severe necrotizing infection that affects the upper urinary tract, involving the renal parenchyma and, in some instances, the perirenal tissues of the kidney. This condition frequently leads to gas formation in the renal parenchyma, collecting system, or perinephric tissue. Emphysematous pyelitis (gas in the renal pelvis) or emphysematous cystitis (gas within the bladder wall and lumen) may occur independently of associated EPN.

Diabetes mellitus represents the most prevalent risk factor, found in over 90% of patients diagnosed with EPN.[1] EPN is a life-threatening disease, with reported mortality rates ranging from 40% to 90%.[2] Clinical diagnosis of the condition closely mirrors acute pyelonephritis, which requires accurate evaluation through imaging, particularly computed tomography (CT) scans. Treatment options for EPN have evolved, with aggressive surgical intervention and more conservative therapeutic approaches, primarily involving percutaneous drainage and antimicrobials.[3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae are the most common pathogens associated with EPN, accounting for 49% to 67% and 20% to 24% of cases, respectively. Other reported organisms include Proteus, Enterococcus, Clostridium, Aspergillus, and, rarely, Candida spp. In some instances, infections exhibit polymicrobial characteristics.[3][4][5][6]

Epidemiology

In more than 90% of cases, patients with EPN have diabetes mellitus, obstructive uropathy, and hypertension as the most common risk factors.[1][7][8] Patients with EPN without diabetes typically present with immunocompromising conditions, including alcohol use disorder, tuberculosis, or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Prior history of urological procedures, previous antibiotic use, or hospitalization does not appear to be relevant risk factors for the development of EPN.

EPN is more prevalent in older patients and females (4:1), likely because women typically have higher rates of urinary tract infections.[8] Adverse outcome risk factors encompass advanced age, altered mentation, acute renal failure, thrombocytopenia, hypoalbuminemia, severe proteinuria, polymicrobial infections, and shock. The potential impact of geographical distribution is noted, with increased reported cases in Asia considered a contributing risk factor.[9][10]

Pathophysiology

Uncontrolled diabetes can cause bacterial propagation and disease progression due to high tissue glucose levels, impaired oxygen supply to the kidneys, and microvascular disease.[7] Gas accumulation observed in EPN is likely a consequence of microbial fermentation of glucose and lactate, producing gases such as carbon dioxide, hydrogen, and nitrogen.[11] Urinary tract obstructions can reduce renal blood flow and tissue perfusion, exacerbating the infection.[12]

History and Physical

The onset of symptoms of EPN may unfold suddenly or gradually over 2 to 3 weeks. EPN may be clinically indistinguishable from severe, acute pyelonephritis based on clinical presentation alone. Fevers, chills, dysuria, nausea, and vomiting are the presenting symptoms and signs of EPN. Other physical signs include abdominal pain, loin tenderness, and pneumaturia or palpable crepitus.[13][14]

Evaluation

Laboratory findings may include pyuria, leukocytosis, hyperglycemia, and elevated serum creatinine.[14] Bacteremia is also relatively common. CT imaging is the most effective diagnostic tool to detect EPN in individuals with 100% sensitivity compared to ultrasonography (69%) and plain film radiography (65%).[7]

Classification

EPN can be classified into 3 different schemas based on radiological findings.

Michaeli et al classification: In 1984, Michaeli et al first classified EPN based on the findings of plain abdominal film of the kidney, ureter, and bladder, and intravenous pyelogram.[15] The classification includes the below-mentioned stages.

- Stage I: Gas in the renal parenchyma or perinephric tissue

- Stage II: Gas in the kidney and its surroundings

- Stage III: Extension of gas through fascia or bilateral disease

Wan et al classification: In 1996, Wan et al introduced a classification system categorizing patients into 2 groups based on CT findings.[16]

- Type I: Renal necrosis with the presence of gas but no fluid

- Type II: Parenchymal gas associated with fluid in the renal parenchyma, perinephric space, or collecting system

Huang and Tseng classification: In 2000, Huang and Tseng published a different classification based on the extent of disease observed on CT scans, providing a more detailed description with additional subcategories.[11] This classification system was grouped into 4 classes, as mentioned below.

Table. Huang and Tseng Classification of EPN

| Classes | Extent of Disease |

| Class 1 | Gas is present only in the collecting system (ie, emphysematous pyelitis) |

| Class 2 | Gas is present in the renal parenchyma without extending to the extrarenal space |

| Class 3 |

Extension into the extrarenal space is classified as follows:

|

| Class 4 | Bilateral EPN or a solitary functioning kidney with EPN |

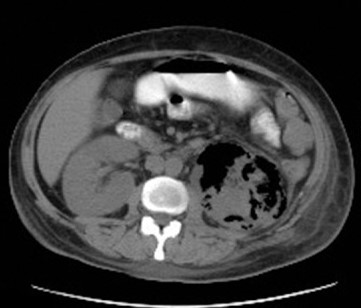

The Huang and Tseng classification system has shown a correlation between a higher class, indicating more extensive disease, with an increased risk of unfavorable outcomes. Differentiating between classes is crucial for accurate prognosis and treatment planning. Emphysematous pyelitis, which responds well to antibiotic treatment alone, has a prognosis similar to pyelonephritis. In contrast, EPN, with a higher mortality rate, requires urgent procedural intervention (see Image. Emphysematous Pyelonephritis).

Treatment / Management

Initial Approach

The initial treatment approach should involve aggressive resuscitation, ensuring adequate intravenous hydration, oxygen supply, blood sugar control by utilizing insulin, and the administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Antibiotics

Empiric antibiotics should cover common bacteria, such as E coli, K pneumoniae, and Proteus mirabilis, that cause urinary tract infections. Additional consideration should be given to coverage for Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterococcus species. The preferred single-agent treatment options may include third- or fourth-generation cephalosporins or carbapenems. The administration of empiric antibiotics is crucial in reducing the mortality rates in gram-negative systemic infections.

An alternative option for combination therapy involves amikacin and a third-generation cephalosporin, given the low antibiotic resistance rates observed among E coli, K pneumoniae, and P mirabilis for amikacin.[8] Fluoroquinolones should not be chosen as the primary option for empirical treatment due to the high levels of resistance resulting from their excessive use.[17](B3)

The transition from intravenous to oral antibiotics and the selection of specific antibiotics are typically guided by clinical improvement, as evidenced by the absence of fever, leukocytosis, and overall enhancement in the patient's well-being. This decision is complemented by culture and antimicrobial resistance testing results. The standard duration of treatment is 2 weeks, although it may vary based on individual cases.

Percutaneous drainage

In addition to antibiotics, percutaneous drainage is recommended for patients with EPN. Antibiotic treatment is likely sufficient for patients with isolated emphysematous pyelitis, and deferring drainage can be considered. Cultures from drainage should be obtained to guide antibiotic therapy. Importantly, urine culture results may not always align with drainage or surgical cultures.[4][18] The removal of the drainage catheter depends on clinical improvement, evidenced by decreased drain output while in the correct anatomical position.(B2)

Relief of obstruction

Relieving the obstruction is crucial when EPN is associated with urinary tract obstruction, such as hydronephrosis. This can be achieved through the use of percutaneous nephrostomy catheters or ureteral stents.

Nephrectomy

The preferred treatment for EPN has transitioned away from invasive operations, such as nephrectomy or open drainage, favoring more conservative approaches, such as percutaneous drainage with antibiotics.[7][19] This transformation is likely attributable to improvements in imaging modalities, improved antibiotic practices, and advancements in drainage technology. These factors have contributed to a notable reduction in the mortality rate associated with EPN, now at 21%, down from historical rates ranging from 40% to 90%.[12][20](A1)

In a meta-analysis conducted by Aboumarzouk et al, emergent nephrectomy, percutaneous drainage, and medical management alone were compared.[21] The overall mortality rate was approximately 18%, with both percutaneous drainage and medical management alone demonstrating significantly lower mortality rates compared to emergent nephrectomy. Although, currently, nephrectomy is less commonly selected as the primary treatment, it may still be necessary for patients who do not respond to conservative therapy. The choice of nephrectomy type—simple, radical, or laparoscopic—depends on the patient's clinical condition and the extent of the disease.[22] Therefore, current treatment recommendations advocate using conservative strategies, such as endoscopic or percutaneous drainage, for renal preservation. Nephrectomy should only be considered if these approaches prove ineffective.[13][23](B2)

Management Approach

Huang and Tseng have proposed a management approach for EPN based on clinico-radiological classification,[11][13] as mentioned below.

Classes 1 and 2 EPN: Medical management alone or combined with percutaneous drainage can yield favorable outcomes.

Classes 3A and 3B EPN: These are further divided into 2 categories, as listed below.

- In patients with fewer than 2 risk factors: Medical management plus percutaneous drainage yields a survival rate of 85%.

- In patients with more than 2 risk factors: Medical management plus percutaneous drainage proved unsuccessful in 92% of cases, with a higher proportion of patients requiring nephrectomy in this group.

Risk factors associated with increased mortality include diabetes mellitus, thrombocytopenia, acute renal failure, altered level of consciousness, and shock.

Class 4 EPN: The initial step remains medical management plus percutaneous drainage.

In any class of EPN, if renal preservation with medical management and percutaneous drainage proves unsuccessful, the subsequent step is nephrectomy.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for EPN includes conditions that may present with similar clinical presentation or imaging findings. Some of the key differentials to consider are mentioned below.

Severe acute pyelonephritis: This condition entails inflammation of the renal parenchyma. Clinically, distinguishing EPN from severe acute pyelonephritis can be challenging; hence, imaging is crucial in diagnosis.

Renal abscess: This condition is characterized by the accumulation of pus within the kidney, and it may present with symptoms resembling EPN, including fever, urinary symptoms, and flank pain. In some cases, gas production within the abscess can result in the presence of air in imaging studies.

Renal trauma: Blunt or penetrating injury to the kidney can disrupt tissue and blood vessels, allowing air entry into the renal parenchyma.

Renal infarction: This condition results from compromised blood flow to a part of the kidney, causing tissue damage. Renal infarction can present with similar symptoms and may sometimes be associated with gas in the renal parenchyma.

Gas-forming infections: Infections caused by gas-forming bacteria can extend into the renal tissues, resulting in the presence of air. This may encompass conditions such as necrotizing fasciitis and gas gangrene.

Anatomic fistulas: Abnormal connections between the urinary tract and gastrointestinal tract or other structures can allow the air to enter the renal parenchyma.

Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: This condition is a chronic, destructive form of pyelonephritis that can lead to renal parenchymal destruction. Although it may not typically involve gas formation, it can share some clinical features with EPN.

Iatrogenic causes: Procedures such as percutaneous nephrostomy or surgical interventions may introduce air into the renal parenchyma.

Prognosis

EPN is a life-threatening condition associated with septic complications that require urgent attention. In a systematic review of 37 studies encompassing 1145 cases of EPN and pyelitis, the overall pooled mortality rate was 12.5 %. However, mortality rates varied based on the severity of the disease.[14] Higher mortality rates are associated with extensive disease and its correlation with confusion, thrombocytopenia, severe proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, hyponatremia, acute kidney injury, and septic shock.

The Huang and Tseng classification system has shown a correlation between a higher class, indicating more extensive disease, with an increased risk of unfavorable outcomes.[11]

Complications

EPN can lead to various severe complications, including the formation of renal abscesses, acute renal failure, perinephric spread of infection, pneumoperitoneum, septic shock, multiple organ failure, and recurrence.[24]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with risk factors, especially those with diabetes, should be educated about the condition and symptoms that warrant medical attention. Early diagnosis and management of urinary tract infections, combined with good glycemic control, can help prevent the development of emphysematous pyelonephritis.[25]

Specific measures can be adopted and practiced to prevent urinary tract infections, including maintaining proper hygiene, urinating before and immediately after intercourse, and staying hydrated. By doing so, introducing bacteria into the urinary tract can potentially be stopped, and the progression to EPN can be prevented.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Collaboration among physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other hospital staff is essential for the care of patients with EPN. Healthcare providers must, first and foremost, possess the necessary clinical skills and expertise for diagnosing, evaluating, and treating this condition. This involves proficiency in recognizing symptoms, interpreting radiological findings, initiating treatment promptly, and identifying potential complications. Patients diagnosed with EPN should receive combined treatment from a urologist and an infectious disease specialist. Interventional radiology may be necessary for percutaneous drainage in cases requiring the drainage of gas and purulent material.

A strategic approach based on evidence-based guidelines and individualized care plans tailored to each patient's unique circumstances is vital. Effective communication among interprofessional healthcare professionals fosters a collaborative environment that shares information, encourages questions, and promptly addresses concerns, especially in critical, life-threatening conditions. Coordination among team members minimizes errors, reduces delays, and enhances patient safety. This approach ultimately results in improved outcomes and patient-centered care, prioritizing the well-being and satisfaction of those affected.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Emphysematous Pyelonephritis. CT features of left-sided emphysematous pyelonephritis (axial cut).

Nasr AA, Kishk AG, Sadek EM, Parayil SM. A case report of emphysematous pyelonephritis as a first presentation of diabetes mellitus. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2013;15(12):e10384. doi:10.5812/ircmj.10384, and is available under a Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0.

References

Smitherman KO, Peacock JE Jr. Infectious emergencies in patients with diabetes mellitus. The Medical clinics of North America. 1995 Jan:79(1):53-77 [PubMed PMID: 7808095]

Falagas ME, Alexiou VG, Giannopoulou KP, Siempos II. Risk factors for mortality in patients with emphysematous pyelonephritis: a meta-analysis. The Journal of urology. 2007 Sep:178(3 Pt 1):880-5; quiz 1129 [PubMed PMID: 17631348]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKoch GE, Johnsen NV. The Diagnosis and Management of Life-threatening Urologic Infections. Urology. 2021 Oct:156():6-15. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2021.05.011. Epub 2021 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 34015395]

Jain A, Manikandan R, Dorairajan LN, Sreenivasan SK, Bokka S. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: Does a standard management algorithm and a prognostic scoring model optimize patient outcomes? Urology annals. 2019 Oct-Dec:11(4):414-420. doi: 10.4103/UA.UA_17_19. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31649464]

Thapa B, Bhusal N. Candidal emphysematous pyelonephritis: A case report on rare and challenging clinical entity. IJU case reports. 2021 Jul:4(4):259-262. doi: 10.1002/iju5.12303. Epub 2021 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 34258544]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchutz EA, Zabott AP, Boaretto RBB, Toyama G, Morais CF, Moroni JG, Oliveira CS. Emphysematous pyelonephritis caused by C. glabrata. Jornal brasileiro de nefrologia. 2022 Jul-Sep:44(3):447-451. doi: 10.1590/2175-8239-JBN-2020-0184. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33760910]

Somani BK, Nabi G, Thorpe P, Hussey J, Cook J, N'Dow J, ABACUS Research Group. Is percutaneous drainage the new gold standard in the management of emphysematous pyelonephritis? Evidence from a systematic review. The Journal of urology. 2008 May:179(5):1844-9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.019. Epub 2008 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 18353396]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLu YC, Hong JH, Chiang BJ, Pong YH, Hsueh PR, Huang CY, Pu YS. Recommended Initial Antimicrobial Therapy for Emphysematous Pyelonephritis: 51 Cases and 14-Year-Experience of a Tertiary Referral Center. Medicine. 2016 May:95(21):e3573. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003573. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27227920]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKarthikeyan VS, Manohar CMS, Mallya A, Keshavamurthy R, Kamath AJ. Clinical profile and successful outcomes of conservative and minimally invasive treatment of emphysematous pyelonephritis. Central European journal of urology. 2018:71(2):228-233. doi: 10.5173/ceju.2018.1639. Epub 2018 Apr 16 [PubMed PMID: 30038815]

Wu SY, Yang SS, Chang SJ, Hsu CK. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: classification, management, and prognosis. Tzu chi medical journal. 2022 Jul-Sep:34(3):297-302. doi: 10.4103/tcmj.tcmj_257_21. Epub 2022 Apr 13 [PubMed PMID: 35912050]

Huang JJ, Tseng CC. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: clinicoradiological classification, management, prognosis, and pathogenesis. Archives of internal medicine. 2000 Mar 27:160(6):797-805 [PubMed PMID: 10737279]

Pontin AR, Barnes RD. Current management of emphysematous pyelonephritis. Nature reviews. Urology. 2009 May:6(5):272-9. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2009.51. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19424175]

Ubee SS, McGlynn L, Fordham M. Emphysematous pyelonephritis. BJU international. 2011 May:107(9):1474-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09660.x. Epub 2010 Sep 14 [PubMed PMID: 20840327]

Desai R, Batura D. A systematic review and meta-analysis of risk factors and treatment choices in emphysematous pyelonephritis. International urology and nephrology. 2022 Apr:54(4):717-736. doi: 10.1007/s11255-022-03131-6. Epub 2022 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 35103928]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMichaeli J, Mogle P, Perlberg S, Heiman S, Caine M. Emphysematous pyelonephritis. The Journal of urology. 1984 Feb:131(2):203-8 [PubMed PMID: 6366247]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWan YL, Lee TY, Bullard MJ, Tsai CC. Acute gas-producing bacterial renal infection: correlation between imaging findings and clinical outcome. Radiology. 1996 Feb:198(2):433-8 [PubMed PMID: 8596845]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHsueh PR, Lau YJ, Ko WC, Liu CY, Huang CT, Yen MY, Liu YC, Lee WS, Liao CH, Peng MY, Chen CM, Chen YS. Consensus statement on the role of fluoroquinolones in the management of urinary tract infections. Journal of microbiology, immunology, and infection = Wei mian yu gan ran za zhi. 2011 Apr:44(2):79-82. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2011.01.015. Epub 2011 Jan 18 [PubMed PMID: 21439507]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKapoor R, Muruganandham K, Gulia AK, Singla M, Agrawal S, Mandhani A, Ansari MS, Srivastava A. Predictive factors for mortality and need for nephrectomy in patients with emphysematous pyelonephritis. BJU international. 2010 Apr:105(7):986-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08930.x. Epub 2009 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 19930181]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMisgar RA, Mubarik I, Wani AI, Bashir MI, Ramzan M, Laway BA. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: A 10-year experience with 26 cases. Indian journal of endocrinology and metabolism. 2016 Jul-Aug:20(4):475-80. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.183475. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27366713]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCiccarese F, Brandi N, Corcioni B, Golfieri R, Gaudiano C. Complicated pyelonephritis associated with chronic renal stone disease. La Radiologia medica. 2021 Apr:126(4):505-516. doi: 10.1007/s11547-020-01315-7. Epub 2020 Nov 27 [PubMed PMID: 33245481]

Aboumarzouk OM, Hughes O, Narahari K, Coulthard R, Kynaston H, Chlosta P, Somani B. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: Time for a management plan with an evidence-based approach. Arab journal of urology. 2014 Jun:12(2):106-15. doi: 10.1016/j.aju.2013.09.005. Epub 2013 Nov 19 [PubMed PMID: 26019934]

Khaira A, Gupta A, Rana DS, Gupta A, Bhalla A, Khullar D. Retrospective analysis of clinical profile prognostic factors and outcomes of 19 patients of emphysematous pyelonephritis. International urology and nephrology. 2009 Dec:41(4):959-66. doi: 10.1007/s11255-009-9552-y. Epub 2009 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 19404766]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBatirel A, Regmi SK, Singh P, Mert A, Konety BR, Kumar R. Urological infections in the developing world: an increasing problem in developed countries. World journal of urology. 2020 Nov:38(11):2681-2691. doi: 10.1007/s00345-020-03120-3. Epub 2020 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 32108257]

Min JW, Lee SK, Ko YM, Kwon KW, Lim JU, Lee YB, Lee HW, Won YD, Kim YO. Emphysematous pyelonephritis initially presenting as a spontaneous subcapsular hematoma in a diabetic patient. Kidney research and clinical practice. 2014 Sep:33(3):150-3. doi: 10.1016/j.krcp.2014.05.001. Epub 2014 Jul 8 [PubMed PMID: 26877965]

Fatima R, Jha R, Muthukrishnan J, Gude D, Nath V, Shekhar S, Narayan G, Sinha S, Mandal SN, Rao BS, Ramsubbarayudu B. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: A single center study. Indian journal of nephrology. 2013 Mar:23(2):119-24. doi: 10.4103/0971-4065.109418. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23716918]