Introduction

Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy is a reversible myocardial injury that presents with distinctive regional wall abnormalities of the left ventricle — first identified and discussed in the early 1990s in Japan. This condition, predominantly found in postmenopausal females, usually presents after significant emotional or physical stressors. On presentation, patients have signs and symptoms of typical acute coronary artery syndrome (cardiac enzyme elevation, ischemic electrocardiogram changes, and chest pain) but lack coronary obstruction on angiographic evaluation.[1] Different forms of this cardiomyopathy over time are seen in patients and are widely categorized into two categories.[2]

Typical Variant

This type of Takotsubo involves the apical ballooning of the left ventricle during systole with likely hyperkinesis of the basal segments. The majority of patients with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy syndrome fall into the typical variant category.

Atypical Variants

This type of Takotsubo involves the basal, focal, mid-ventricular, biventricular (apical and right ventricle), isolated right ventricular, and global variants.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Multiple triggers are associated with mid-ventricular Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. However, the exact mechanism of this condition is not fully understood—two separate categories, which include physical triggers and emotional triggers, are known to play a role in the process of developing this cardiomyopathy.

Some of these triggers are listed below:[2]

Emotional triggers:

- Death of a family member

- Sudden bankruptcy

- Divorce

- Loss of employment

Physical triggers:

- Stroke

- Sepsis

- Vaginal delivery

- Chemotherapy

Epidemiology

Based on a systemic review of studies, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy accounts for approximately 2% of the ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) population, with about 90% of the cases found in post-menopausal women. The mortality rate in hospitals is 1.1% among these patients, and approximately 3.5% of these patients showed recurrence of this phenomenon.[3] Mid-ventricular Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is a rare form that accounts for about 14.6% of patients with this syndrome. These patients have mid-ventricular ballooning and apical/basal hyperdynamic segments.[4]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology behind this disorder is not truly well understood; however, there are specific mechanisms that are involved in this disorder. Proposed mechanisms are a combination of spasm of the coronary arteries, microvascular dysfunction, and catecholamine surge. The role of catecholamines during the surge is the cause of microvascular dysfunction resulting in catecholamine-induced myocardial toxicity.[5]

Histopathology

Limited data does suggest histopathologic signs of catecholamine toxicity which include but are not limited to:[6][7][8][9]

- Interstitial fibrosis with evidence of cellular infiltration

- Interstitial fibrosis without evidence of cellular infiltration

- Mononuclear infiltrates and contraction band necrosis

- No histopathologic evidence of myocarditis

History and Physical

A typical presentation of mid-ventricular Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is similar to the other known variants of this syndrome, which mimic acute coronary syndrome (chest pain, ECG changes, and elevation of cardiac enzymes) and is triggered by stress. It is vital to obtain an accurate history of these patients as they might be able to communicate recent stressors. These include the death of a loved one, suffering from a natural disaster, the news of a new medical diagnosis, divorce, gambling losses, or financial bankruptcy. In the International Takotsubo Registry, approximately 28% of the patient who presented with this type of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and the other kinds of Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy had reported triggers of emotional nature. About 36% had a physical trigger such as infection or respiratory failure, approximately 8% had both physical and emotional triggers, and 28.5% did not have any emotional or physical triggers identified.[4]

Evaluation

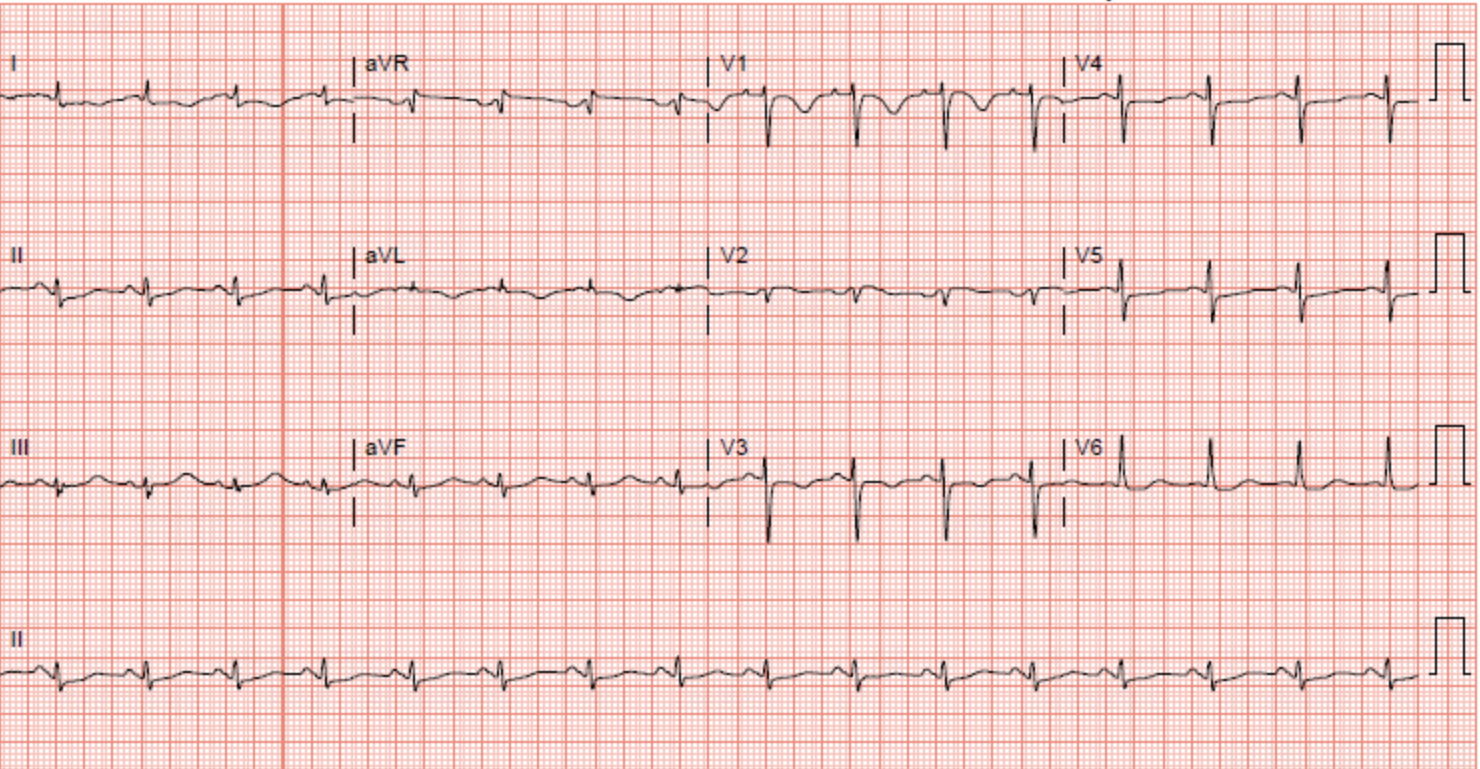

Evaluation of this type of stress cardiomyopathy involves an electrocardiogram to evaluated for ST-segment elevation commonly found in the anterior precordial leads. Data from the International Takotsubo Registry Study shows ST-segment elevation in approximately 44% of the patients with any type of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy.[4][10] Other less common electrocardiogram findings include ST-segment depression, QT interval prolongation, T wave inversion, and abnormal Q waves.[4][11][9][12] The absence of electrocardiogram changes is known to be specific for mid-ventricular Takotsubo cardiomyopathy.

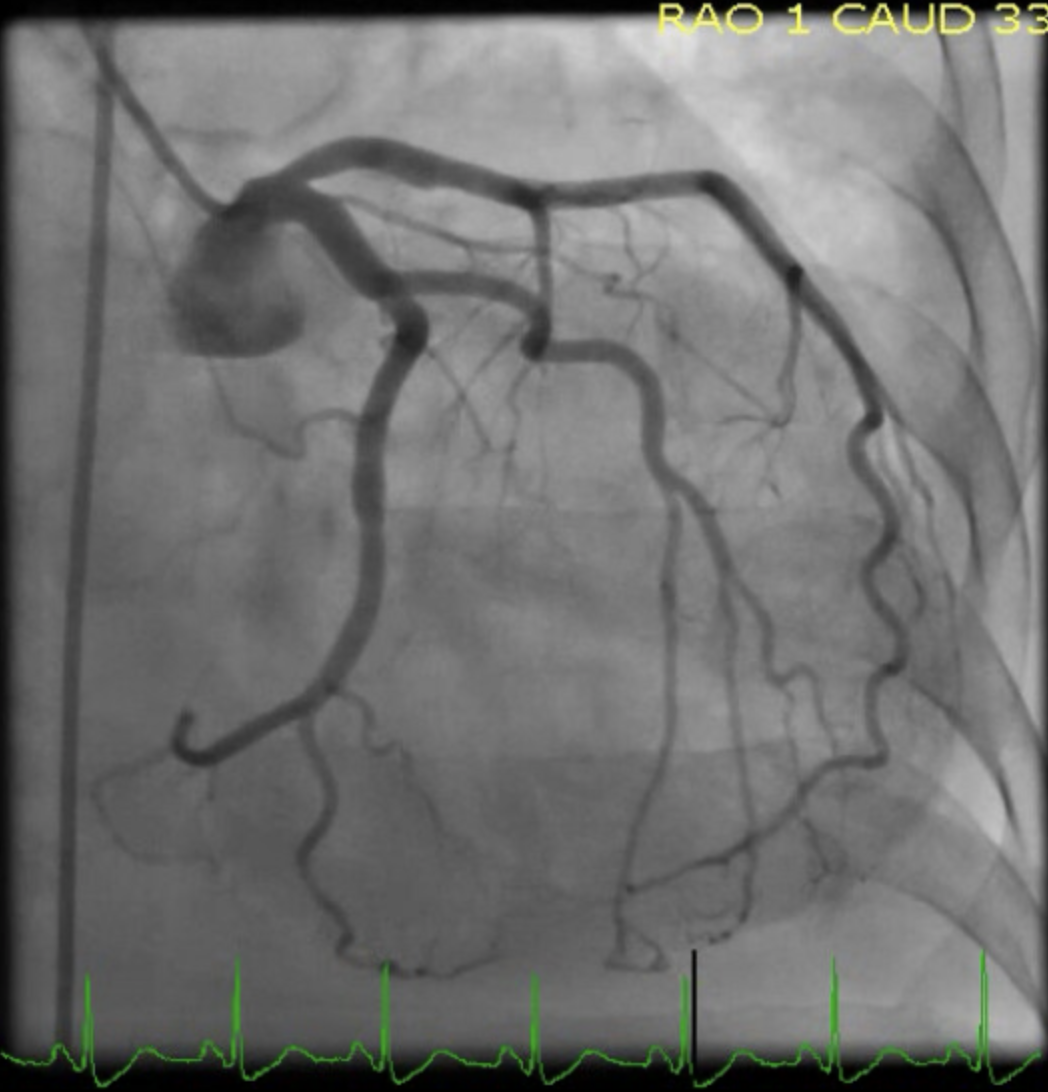

Cardiac enzymes are above the reference range in the majority of patients with mid-ventricular Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and other types of Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy. In the International Takotsubo Registry, the average initial troponin was approximately eight times the upper limit of normal in patients with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, including mid-ventricular Takotsubo cardiomyopathy.[4] In a case, a seventy-seven-year-old female presented to the hospital with symptoms of chest pain. Her electrocardiogram changes were concerning of ischemia in the anterolateral wall. Her troponin-I was elevated and peaked at 0.11. The patient underwent a left heart catheterization, which showed normal coronaries, and a transthoracic echocardiogram showed akinesis to dyskinesis of the mid-anteroseptum, mid-inferoseptum, mid-inferior wall, mid-anterior wall, and the mid-anterolateral wall. This pattern is consistent with mid-ventricular takotsubo cardiomyopathy.

Treatment / Management

This type of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is a transient disorder that is managed conservatively with supportive therapy. A provider should first focus on eliminating the physical and emotional stressors, which might help subside the patient's symptoms. However, a specific subset of these patients might develop acute decompensated congestive heart failure, and subsequently, cardiogenic shock. The treatment of such patients is based on heart failure and shock management guidelines. It is essential to delineate left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction in these patients as it is imperative to prevent volume depletion and vasodilator therapy. Therefore an urgent transthoracic echocardiogram in patients who are in cardiogenic shock and suspected to have LVOT obstruction is essential in the early management of these patients. Patients with mid-ventricular Takotsubo cardiomyopathy are also at risk of developing an intraventricular thrombus in the setting of severe left ventricular dysfunction. Approximately 1% to 1.5% of patients with all types of stress cardiomyopathy, including mid-ventricular cardiomyopathy in the International Takotsubo Registry Study, were found to have an LV thrombus. In the management of patients with LV thrombus, the use of warfarin is recommended for three months; however, the duration of systemic anticoagulation can be modified based on the rate at which the LV dysfunction improves, and the thrombus resolves.[4]

Differential Diagnosis

Patients suspected of having mid-ventricular Takotsubo cardiomyopathy should have acute coronary syndrome ruled out with coronary angiography to ensure that there is not significant coronary artery disease in the territory of the affected walls of the ventricular cavity. It is critical to understand that in some patients, the angiographic analysis will show evidence of concurrent obstructive coronary artery disease; however, the disease in the coronaries will not match the territory of the LV wall motion dysfunction.[13]

Other medical conditions to consider in patients with suspected mid-ventricular Takotsubo cardiomyopathy are as follows:

- An acute coronary syndrome due to cocaine abuse

- Myocarditis

- Acute brain injury in patients with pheochromocytoma

Detailed history, physical exam, and toxicology assays can help narrow our differential diagnoses. Myocarditis is diagnosed with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, which will show myocardial inflammation and scar. Patients with pheochromocytoma will have clinical findings and symptoms of tachycardia, hypertension, diaphoresis, and headache.[14][15][16]

Prognosis

Patients with mid-ventricular Takotsubo cardiomyopathy mostly recover with conservative management; patients who survive the acute phase of this syndrome recover their LV ejection fraction within four weeks.[17][9][18]

Complications

The risk of in-hospital complications in patients with mid-ventricular Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is similar to that in patients with acute coronary syndrome. The combined risk of CPR, ventilatory therapy, cardiogenic shock, and catecholamine use is about 19% for patients with mid-ventricular Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and acute coronary syndrome.[4]

Deterrence and Patient Education

If available, patient education should be provided using resources familiar to the patient, such as online resources and pamphlets.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Educating patients at risk for this type of cardiomyopathy (for example, post-menopausal females) and making a closed-loop communication between them and their providers, can help further improve the management of this syndrome in both the acute phase and long term phase of this syndrome.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Roshanzamir S, Showkathali R. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy a short review. Current cardiology reviews. 2013 Aug:9(3):191-6 [PubMed PMID: 23642025]

Ghadri JR, Wittstein IS, Prasad A, Sharkey S, Dote K, Akashi YJ, Cammann VL, Crea F, Galiuto L, Desmet W, Yoshida T, Manfredini R, Eitel I, Kosuge M, Nef HM, Deshmukh A, Lerman A, Bossone E, Citro R, Ueyama T, Corrado D, Kurisu S, Ruschitzka F, Winchester D, Lyon AR, Omerovic E, Bax JJ, Meimoun P, Tarantini G, Rihal C, Y-Hassan S, Migliore F, Horowitz JD, Shimokawa H, Lüscher TF, Templin C. International Expert Consensus Document on Takotsubo Syndrome (Part I): Clinical Characteristics, Diagnostic Criteria, and Pathophysiology. European heart journal. 2018 Jun 7:39(22):2032-2046. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy076. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29850871]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGianni M, Dentali F, Grandi AM, Sumner G, Hiralal R, Lonn E. Apical ballooning syndrome or takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. European heart journal. 2006 Jul:27(13):1523-9 [PubMed PMID: 16720686]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTemplin C, Ghadri JR, Diekmann J, Napp LC, Bataiosu DR, Jaguszewski M, Cammann VL, Sarcon A, Geyer V, Neumann CA, Seifert B, Hellermann J, Schwyzer M, Eisenhardt K, Jenewein J, Franke J, Katus HA, Burgdorf C, Schunkert H, Moeller C, Thiele H, Bauersachs J, Tschöpe C, Schultheiss HP, Laney CA, Rajan L, Michels G, Pfister R, Ukena C, Böhm M, Erbel R, Cuneo A, Kuck KH, Jacobshagen C, Hasenfuss G, Karakas M, Koenig W, Rottbauer W, Said SM, Braun-Dullaeus RC, Cuculi F, Banning A, Fischer TA, Vasankari T, Airaksinen KE, Fijalkowski M, Rynkiewicz A, Pawlak M, Opolski G, Dworakowski R, MacCarthy P, Kaiser C, Osswald S, Galiuto L, Crea F, Dichtl W, Franz WM, Empen K, Felix SB, Delmas C, Lairez O, Erne P, Bax JJ, Ford I, Ruschitzka F, Prasad A, Lüscher TF. Clinical Features and Outcomes of Takotsubo (Stress) Cardiomyopathy. The New England journal of medicine. 2015 Sep 3:373(10):929-38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406761. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26332547]

Nef HM, Möllmann H, Kostin S, Troidl C, Voss S, Weber M, Dill T, Rolf A, Brandt R, Hamm CW, Elsässer A. Tako-Tsubo cardiomyopathy: intraindividual structural analysis in the acute phase and after functional recovery. European heart journal. 2007 Oct:28(20):2456-64 [PubMed PMID: 17395683]

Karch SB, Billingham ME. Myocardial contraction bands revisited. Human pathology. 1986 Jan:17(1):9-13 [PubMed PMID: 2417934]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFineschi V, Silver MD, Karch SB, Parolini M, Turillazzi E, Pomara C, Baroldi G. Myocardial disarray: an architectural disorganization linked with adrenergic stress? International journal of cardiology. 2005 Mar 18:99(2):277-82 [PubMed PMID: 15749187]

Kurisu S, Sato H, Kawagoe T, Ishihara M, Shimatani Y, Nishioka K, Kono Y, Umemura T, Nakamura S. Tako-tsubo-like left ventricular dysfunction with ST-segment elevation: a novel cardiac syndrome mimicking acute myocardial infarction. American heart journal. 2002 Mar:143(3):448-55 [PubMed PMID: 11868050]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWittstein IS, Thiemann DR, Lima JA, Baughman KL, Schulman SP, Gerstenblith G, Wu KC, Rade JJ, Bivalacqua TJ, Champion HC. Neurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress. The New England journal of medicine. 2005 Feb 10:352(6):539-48 [PubMed PMID: 15703419]

Parkkonen O, Allonen J, Vaara S, Viitasalo M, Nieminen MS, Sinisalo J. Differences in ST-elevation and T-wave amplitudes do not reliably differentiate takotsubo cardiomyopathy from acute anterior myocardial infarction. Journal of electrocardiology. 2014 Sep-Oct:47(5):692-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2014.06.006. Epub 2014 Jun 14 [PubMed PMID: 25022798]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTsuchihashi K, Ueshima K, Uchida T, Oh-mura N, Kimura K, Owa M, Yoshiyama M, Miyazaki S, Haze K, Ogawa H, Honda T, Hase M, Kai R, Morii I, Angina Pectoris-Myocardial Infarction Investigations in Japan. Transient left ventricular apical ballooning without coronary artery stenosis: a novel heart syndrome mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Angina Pectoris-Myocardial Infarction Investigations in Japan. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2001 Jul:38(1):11-8 [PubMed PMID: 11451258]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOgura R, Hiasa Y, Takahashi T, Yamaguchi K, Fujiwara K, Ohara Y, Nada T, Ogata T, Kusunoki K, Yuba K, Hosokawa S, Kishi K, Ohtani R. Specific findings of the standard 12-lead ECG in patients with 'Takotsubo' cardiomyopathy: comparison with the findings of acute anterior myocardial infarction. Circulation journal : official journal of the Japanese Circulation Society. 2003 Aug:67(8):687-90 [PubMed PMID: 12890911]

Hurtado Rendón IS, Alcivar D, Rodriguez-Escudero JP, Silver K. Acute Myocardial Infarction and Stress Cardiomyopathy Are Not Mutually Exclusive. The American journal of medicine. 2018 Feb:131(2):202-205. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.07.039. Epub 2017 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 28860031]

Kassim TA, Clarke DD, Mai VQ, Clyde PW, Mohamed Shakir KM. Catecholamine-induced cardiomyopathy. Endocrine practice : official journal of the American College of Endocrinology and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. 2008 Dec:14(9):1137-49 [PubMed PMID: 19158054]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAko J, Sudhir K, Farouque HM, Honda Y, Fitzgerald PJ. Transient left ventricular dysfunction under severe stress: brain-heart relationship revisited. The American journal of medicine. 2006 Jan:119(1):10-7 [PubMed PMID: 16431176]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDastidar AG, Frontera A, Palazzuoli A, Bucciarelli-Ducci C. TakoTsubo cardiomyopathy: unravelling the malignant consequences of a benign disease with cardiac magnetic resonance. Heart failure reviews. 2015 Jul:20(4):415-21. doi: 10.1007/s10741-015-9489-4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25896529]

Sharkey SW, Lesser JR, Zenovich AG, Maron MS, Lindberg J, Longe TF, Maron BJ. Acute and reversible cardiomyopathy provoked by stress in women from the United States. Circulation. 2005 Feb 1:111(4):472-9 [PubMed PMID: 15687136]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDesmet WJ, Adriaenssens BF, Dens JA. Apical ballooning of the left ventricle: first series in white patients. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2003 Sep:89(9):1027-31 [PubMed PMID: 12923018]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence