Introduction

Nocardia is a Gram-variable, aerobic, weakly acid-fast bacteria that rarely causes ocular disease, of which corneal infection is the most common.[1] The diagnosis of Nocardia keratitis is often missed or delayed due to a lack of familiarity or a non-specific presentation, which may mimic other more common causative organisms.[1] Notably, Nocardia keratitis has a variable response to most first-line medications used for bacterial keratitis, such as fluoroquinolones.[2] Thus, patients may suffer from significant morbidity until reaching a proper diagnosis.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Although originally classified as a fungus, Nocardia is a genus of filamentous bacteria that contains over 80 species.[1] Nocardia is ubiquitous in the environment, representing the microflora of water, dust, soil, mud, and decaying vegetation.[1] As Nocardia species do not present as normal flora within the eye, Nocardia keratitis must occur secondary to exposure to bacteria in the environment.[2]

For several decades, Nocardia asteroides was the most common species to be isolated from cases of Nocardia keratitis; however, recent advances in PCR and RNA sequencing have demonstrated that other species such as Nocardia arthritidis are more common in certain populations.[3]

Ocular exposure to soil or plant matter was found to be a common historical point in nearly half of all Nocardia keratitis cases.[4] The most common risk factor for Nocardia keratitis is corneal trauma. In one case series, trauma was the inciting factor in 25% of cases.[5] Other known risk factors include prior ocular surgery such as LASIK or PRK, topical corticosteroid use, and contact lens wear, especially in the setting of extended use or improper hygiene.[6][7][2][8]

Epidemiology

Nocardia is thought to be more prevalent in the soil of South Asia.[9] As such, clinicians rarely diagnose Nocardia keratitis outside of the Asian continent.[10] A study from Hyderabad in South India estimated Nocardia to have caused 1.7% of bacterial keratitis cases.[11] Another paper from Tamil in South India indicated that Nocardia was isolated from 8.34% of samples of bacterial keratitis.[12]

Bacterial keratitis of all etiologies tends to more frequently seen in males, young adults, and people in rural areas, likely due to the predisposing need for minor corneal trauma and/or environmental exposure.[2]

Pathophysiology

Nocardia keratitis is a slow-growing infection. One case series found the mean time to presentation to be 24.5 +/- 22.2 days after the initial infection.[13] One of the major virulence factors of Nocardia is trehalose 6,6’-dimycolate, which confers resistance to phagocytosis by inhibiting the integration of phagosomes and lysosomes, thereby decreasing lysosomal enzyme activity.[14][15] The production of superoxide dismutase and subsequently increased levels of catalase additionally allow Nocardia to evade the oxidative killer mechanism of polymorphonuclear leukocytes.[16]

History and Physical

A detailed history is necessary for all patients with suspected ocular infection. Clinicians should give special attention to inquiring about risk factors, as listed above. A history of recent travel to Asia should also raise the clinician’s suspicion of Nocardia keratitis.[10] The symptoms most commonly associated with Nocardia keratitis are non-specific and include severe ocular pain, blepharospasm, photophobia, and eyelid swelling.[2][4]

A comprehensive ocular examination is also for all patients with symptoms suspicious of ocular infection. On slit-lamp examination, Nocardia keratitis classically presents as patchy anterior stromal infiltrates arranged in a wreath pattern with satellite lesions.[1] Infiltrates are often found in the mid-periphery of the cornea adjacent to the region of corneal trauma.[17] However, Nocardia keratitis may also present as a non-specific punctuate epitheliopathy or an ulcer with margins studded with superficial yellow pinhead-sized infiltrates.[4] Though infiltrates are typically superficial, the infection may extend to the stroma.[2]

Evaluation

Clinical diagnosis of Nocardia keratitis could theoretically be made based upon the symptoms and signs elicited by a thorough history and physical examination alone. However, the gold standard for diagnosis of Nocardia keratitis is an inoculation and growth of Nocardia species in culture media following corneal scraping and/or biopsy.[2] Nocardia colonies will grow on a variety of culture media, including blood agar, chocolate agar, and Sabouraud agar[12]; nonetheless, clinical suspicion for Nocardia should be communicated to the lab such that specific measures can be taken to optimize recognition of the species. Notably, Nocardia is a slow-growing organism; though growth usually appears within 5 to 7 days, at least two weeks of inoculation should be allowed as false negatives may otherwise occur. Isolation of Nocardia is significant as the pathogen is not a common contaminant.[2]

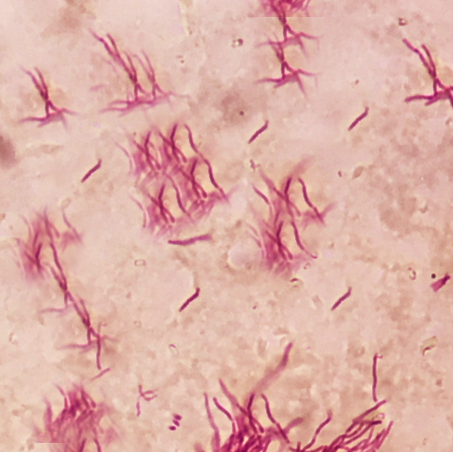

Multiple strategies beyond culture exist for evaluation of suspected Nocardia keratitis. One retrospective study identified several cases in which Gram stain or 1% acid-fast (Ziehl-Neelsen) stain allowed for early diagnosis.[4] In vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM) is an excellent non-invasive diagnostic tool that allows for the evaluation of cells of the cornea in real-time. Nocardia will appear on IVCM as filamentous, highly reflective structures, similar to many fungi; a history of trauma with organic matter will provide clinical context to findings on IVCM. Notably, the sensitivity of IVCM is highly dependent on the expertise of the user. Newer evidence suggests an increasing role of techniques such as the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), gene sequencing, DNA sequencing, and pyrosequencing in the detection of Nocardia from infected tissue.[3][18][19][20]

Treatment / Management

Amikacin 2 to 2.5% hourly remains the first-line treatment for Nocardia keratitis.[12] Nocardia keratitis exhibits a variable response to standard initial therapy for other forms of bacterial keratitis. One study of 20 Nocardia isolates from ocular infections demonstrated that only 55% were responsive to ciprofloxacin, whereas all isolates were susceptible to treatment with amikacin.[21] Given that culture results often require 5 to 7 days to produce a positive result, empiric therapy should not delay if the clinician has a high suspicion for Nocardia keratitis. Topical therapy should continue until achieving complete resolution of the infection; the mean duration for complete resolution of infection following daily administration of amikacin 2.5% is approximately 38 days.[4](B2)

Some cases of amikacin resistant Nocardia exist.[17][22] In these cases, second-line treatments, including topical tobramycin or gentamicin 1.4%, imipenem 0.5%, or moxifloxacin 0.5%, are potential options.[1] Though sulfonamides (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) were previously considered the mainstay of therapy, they have fallen out of favor due to a significantly higher minimum inhibitory concentration than amikacin.[2] Topical corticosteroids should be avoided as they are associated with an increased risk for corneal perforation and endophthalmitis.[2](B3)

Occasionally, Nocardia may extend beyond the cornea and cause secondary scleritis.[4] Scleritis in the setting of prior ocular trauma is highly suspicious for Nocardia infection and warrants immediate surgical debridement before receiving a confirmatory result from culture or PCR. In addition to topical amikacin 2%, scleritis should have treatment with a subconjunctival injection of 100 mg amikacin.[23] Persistent scleritis despite repeat subconjunctival injection may require initiation of oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 160 mg/800 mg hourly.[17](B2)

Though medical management is generally sufficient for the treatment of Nocardia keratitis, surgical treatment may be necessary in the case of medication non-responsiveness, progressive corneal thinning, or significant scleral involvement.[2] Surgical options include lamellar keratectomy, penetrating keratoplasty, and conjunctival flap.[24] In particular, lamellar keratectomy may be useful for removing infected tissue and increasing penetration of topical antibiotics.[25] Few reports exist on the use of surgery for the treatment of Nocardia keratitis, but the outcomes appear to be good.[12](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

Both Nocardia keratitis and fungal keratitis present with satellite infiltrates on slit-lamp examination and filamentous structures in culture.[1] Occasionally, Nocardia may present on slit-lamp examination as cotton-wool infiltrates with irregular and feathery margins, an atypical presentation similar to fungal keratitis.[4][26] Moreover, the classic “wreath-like” pattern of Nocardia keratitis has been described in some cases of fungal keratitis.[27] Therefore, fungal keratitis may mimic Nocardia may mimic fungal keratitis, and vice versa. Nocardia keratitis may be distinguished from fungal keratitis by a history of trauma with organic matter, protracted time course for infection to develop, and a superficial granular appearance of lesions on slit-lamp examination.[2]

Another pathogen that may mimic Nocardia is Moraxella, a gram-negative diplococcus that may produce ulcers on the inferior cornea in select patient groups, including patients with diabetes, alcoholics, and the malnourished.[28] Both Nocardia and Moraxella will grow colonies on blood agar and chocolate agar; however, Nocardia stains Gram-positive and will develop filamentous structures in culture. Unlike Nocardia, Moraxella keratitis typically presents on the inferior portion of the cornea and does not spread beyond the cornea.[2]

Mycobacteria are aerobic, Gram-neutral bacilli that cause slow-developing corneal infections similar to Nocardia. Both Nocardia and Mycobacteria will stain positive with acid-fast (Ziehl-Neelsen) staining and grow on blood agar. However, Mycobacteria is more likely to reveal white corneal infiltrates with a “snowflake” or “cracked windshield” appearance on slit-lamp examination.[29] Furthermore, unlike Nocardia, Mycobacteria will grow on Lowenstein-Jensen medium.

Prognosis

With appropriate treatment, Nocardia keratitis tends to heal rapidly with scarring and some peripheral vascularization.[12] If the infection is responsive to medical therapy, visual acuity tends to improve. Patients typically remain asymptomatic with no recurrences. In one case series, nearly all patients regained visual acuity greater than 20/25 following prompt diagnosis and treatment.[30] Poorer outcomes correlate with older age and scleral extension of keratitis.[4]

Complications

Undiagnosed or poorly managed Nocardia keratitis may extend to the adjacent sclera.[4] Nocardia scleritis commonly presents with necrosis, hemorrhage, and abscess formation. The episcleral veins may also appear as engorged. Initial treatment for Nocardia scleritis involves debridement, topical amikacin, and subconjunctival amikacin, as listed above.[2]

Nocardia keratitis may also rarely progress to endophthalmitis, though this infection more typically occurs due to hematogenous spread of an extraocular Nocardia infection in immunocompromised individuals.[2] Endophthalmitis classically presents as a significant inflammation of the anterior chamber and hypopyon. Yellow-white nodules may also be seen overlying the iris. Outcomes in Nocardia endophthalmitis are usually very poor, but vision may be salvaged with early detection and aggressive therapy with both topical and intravitreal antibiotics.[2]

There are no reports of the incidence of these complications as an extension of Nocardia keratitis in the literature. Significant delays in treatment may result in corneal perforation or permanent blindness.[7]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients who use contact lenses should receive counsel regarding maintaining proper care of their lens and avoid extended wear. Individuals with significant regular exposure to soil or plant matter should wear protective eyewear as appropriate.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Nocardia is a rare and often misdiagnosed cause of ocular infection, of which the most common is keratitis.

- The pathognomonic finding on slit-lamp examination is patchy anterior stromal infiltrates arranged in a wreath pattern.

- Diagnosis is by corneal scrapings and culture. Cultures often require 5 to 7 days to develop.

- First-line treatment is topical amikacin. Corticosteroids should be avoided.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The majority of patients with Nocardia keratitis will present to their primary care provider or the emergency room for evaluation. Prompt referral to an ophthalmologist is necessary as any delay may result in permanent vision loss. Communication between the pathologist, the ophthalmologist, and the microbiologist is especially vital to employ isolation techniques used to identify Nocardia. Close follow-up by an ophthalmologist is required to monitor the improvement of clinical symptoms and findings on slit-lamp examination following initiation of both medical and surgical treatment. The primary clinicians, including the nurse, should educate patients who wear contacts to exercise good hygiene. The patient should not engage in water-related activities while wearing contacts, wash hands regularly, and use a clean, fresh solution for storing the lenses. The patient should understand that at any time they develop a painful red eye, a visit to the eye specialist is in order. Antimicrobial therapy should enlist the assistance of a pharmacist with infectious disease specialty training, who can verify agent selection and dosing, as well as check for any drug interactions that may negatively impact therapy, and report these to the team. Open communication and cooperation between interprofessional healthcare team members is the only way to lower the morbidity of Nocardia keratitis and improve patient outcomes. [Level V]

Media

References

Behaegel J,Ní Dhubhghaill S,Koppen C, Diagnostic Challenges in Nocardia Keratitis. Eye [PubMed PMID: 29219900]

Sridhar MS,Gopinathan U,Garg P,Sharma S,Rao GN, Ocular nocardia infections with special emphasis on the cornea. Survey of ophthalmology. 2001 Mar-Apr; [PubMed PMID: 11274691]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYin X,Liang S,Sun X,Luo S,Wang Z,Li R, Ocular nocardiosis: HSP65 gene sequencing for species identification of Nocardia spp. American journal of ophthalmology. 2007 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 17698022]

DeCroos FC,Garg P,Reddy AK,Sharma A,Krishnaiah S,Mungale M,Mruthyunjaya P, Optimizing diagnosis and management of nocardia keratitis, scleritis, and endophthalmitis: 11-year microbial and clinical overview. Ophthalmology. 2011 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 21276615]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSridhar MS,Sharma S,Reddy MK,Mruthyunjay P,Rao GN, Clinicomicrobiological review of Nocardia keratitis. Cornea. 1998 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 9436875]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePérez-Santonja JJ,Sakla HF,Abad JL,Zorraquino A,Esteban J,Alió JL, Nocardial keratitis after laser in situ keratomileusis. Journal of refractive surgery (Thorofare, N.J. : 1995). 1997 May-Jun; [PubMed PMID: 9183766]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFaramarzi A,Feizi S,Javadi MA,Rezaei Kanavi M,Yazdizadeh F,Moein HR, Bilateral nocardia keratitis after photorefractive keratectomy. Journal of ophthalmic [PubMed PMID: 23275825]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceParsons MR,Holland EJ,Agapitos PJ, Nocardia asteroides keratitis associated with extended-wear soft contact lenses. Canadian journal of ophthalmology. Journal canadien d'ophtalmologie. 1989 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 2659153]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGoel S,Kanta S, Prevalence of Nocardia species in the soil of Patiala area. Indian journal of pathology [PubMed PMID: 8354557]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTrichet E,Cohen-Bacrie S,Conrath J,Drancourt M,Hoffart L, Nocardia transvalensis keratitis: an emerging pathology among travelers returning from Asia. BMC infectious diseases. 2011 Oct 31; [PubMed PMID: 22040176]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGarg P,Rao GN, Corneal ulcer: diagnosis and management. Community eye health. 1999; [PubMed PMID: 17491983]

Lalitha P, Nocardia keratitis. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2009 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 19387343]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGarg P, Fungal, Mycobacterial, and Nocardia infections and the eye: an update. Eye (London, England). 2012 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 22173077]

Silva CL,Tincani I,Brandão Filho SL,Faccioli LH, Mouse cachexia induced by trehalose dimycolate from Nocardia asteroides. Journal of general microbiology. 1988 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 3065451]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFatahi-Bafghi M, Nocardiosis from 1888 to 2017. Microbial pathogenesis. 2018 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 29146497]

Beaman BL,Black CM,Doughty F,Beaman L, Role of superoxide dismutase and catalase as determinants of pathogenicity of Nocardia asteroides: importance in resistance to microbicidal activities of human polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Infection and immunity. 1985 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 3880721]

Johansson B,Fagerholm P,Petranyi G,Claesson Armitage M,Lagali N, Diagnostic and therapeutic challenges in a case of amikacin-resistant Nocardia keratitis. Acta ophthalmologica. 2017 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 27572657]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBrown JM,Pham KN,McNeil MM,Lasker BA, Rapid identification of Nocardia farcinica clinical isolates by a PCR assay targeting a 314-base-pair species-specific DNA fragment. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2004 Aug; [PubMed PMID: 15297512]

Patel JB,Wallace RJ Jr,Brown-Elliott BA,Taylor T,Imperatrice C,Leonard DG,Wilson RW,Mann L,Jost KC,Nachamkin I, Sequence-based identification of aerobic actinomycetes. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2004 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 15184431]

Galor A,Hall GS,Procop GW,Tuohy M,Millstein ME,Jeng BH, Rapid species determination of Nocardia keratitis using pyrosequencing technology. American journal of ophthalmology. 2007 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 17188068]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceReddy AK,Garg P,Kaur I, Speciation and susceptibility of Nocardia isolated from ocular infections. Clinical microbiology and infection : the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2010 Aug; [PubMed PMID: 19832708]

Patel R,Sise A,Al-Mohtaseb Z,Garcia N,Aziz H,Amescua G,Pantanelli SM, Nocardia asteroides Keratitis Resistant to Amikacin. Cornea. 2015 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 26418432]

Cunha LPD,Juncal V,Carvalhaes CG,Leão SC,Chimara E,Freitas D, Nocardial scleritis: A case report and a suggested algorithm for disease management based on a literature review. American journal of ophthalmology case reports. 2018 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 29780901]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTseng SH,Chen JJ,Hu FR, Nocardia brasiliensis keratitis successfully treated with therapeutic lamellar keratectomy. Cornea. 1996 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 8925664]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShah P,Zhu D,Culbertson WW, Therapeutic Femtosecond Laser-Assisted Lamellar Keratectomy for Multidrug-Resistant Nocardia Keratitis. Cornea. 2017 Nov; [PubMed PMID: 28834821]

Lalitha P,Tiwari M,Prajna NV,Gilpin C,Prakash K,Srinivasan M, Nocardia keratitis: species, drug sensitivities, and clinical correlation. Cornea. 2007 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 17413948]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSrinivasan M,Sharma S, Nocardia asteroides as a cause of corneal ulcer. Case report. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1987 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 3551895]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMarioneaux SJ,Cohen EJ,Arentsen JJ,Laibson PR, Moraxella keratitis. Cornea. 1991 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 2019103]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBroadway DC,Kerr-Muir MG,Eykyn SJ,Pambakian H, Mycobacterium chelonei keratitis: a case report and review of previously reported cases. Eye (London, England). 1994; [PubMed PMID: 8013708]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSridhar MS,Sharma S,Garg P,Rao GN, Treatment and outcome of nocardia keratitis. Cornea. 2001 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 11413397]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence