Introduction

Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma is a rare, aggressive malignant tumor accounting for 2% to 3% of all thyroid gland neoplasms. In contrast to differentiated thyroid malignancies such as papillary and follicular thyroid cancers, anaplastic thyroid cancer is undifferentiated. Furthermore, anaplastic thyroid cancer is highly locally invasive, with a propensity for early lymph node positivity and distant metastatic disease.

Anaplastic thyroid cancer typically presents as a rapidly growing anterior neck mass and may have compressive symptoms early in the disease. The diagnosis is typically made by fine needle aspiration cytology, although a core needle biopsy is more sensitive and specific. All patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer should be assessed for systemic disease. While patients with locoregional disease can occasionally be cured, the disease is uniformly fatal with distant spread.[1][2] Treatment can include surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and, more recently, targeted therapy. Recent advances in molecular diagnostics have identified several mutations that could be targeted in the future.[3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of anaplastic thyroid cancer is unknown. Apart from its association with differentiated thyroid cancers in about 20% of cases, anaplastic thyroid cancer has no clear causative factors. Evidence supports the theory that some anaplastic cancers may arise from preexisting differentiated thyroid cancers by dedifferentiation.[4][5]

Epidemiology

Anaplastic thyroid cancer is a rare form of thyroid cancer, accounting for between 1% and 10% of all thyroid cancers globally and 1.7% of cases in the United States.[6] Given the rarity and high mortality rate of this cancer, the precise incidence remains uncertain. Despite its infrequency, anaplastic thyroid cancer is responsible for up to 50% of all deaths related to thyroid cancers. Anaplastic thyroid cancer typically occurs in older individuals with a mean age of 65 and, like other thyroid cancers, is more prevalent in women than in men.[6][7]

Pathophysiology

Anaplastic thyroid cancer is associated with differentiated thyroid cancers, with roughly 20% of patients having a history of differentiated thyroid cancer.[8] In addition, up to a third of patients have coexisting differentiated thyroid cancer, usually papillary thyroid cancer, when they are diagnosed. The molecular pathogenesis is similar to well-differentiated thyroid cancers, and our understanding of these molecular drivers continues to improve with ongoing research.

Mutations in the TERT promoter region and TP53 are common, with TERT promoter mutations associated with RAS and BRAF mutations. Other targetable mutations may be seen, including NTRK and ALK rearrangements.[9] Thyroid-specific rearrangements RET/PTC and PAX8/PPARγ are rarely found in poorly differentiated or undifferentiated thyroid cancer, suggesting that these genetic alterations do not predispose cells to dedifferentiation.[10]

Histopathology

Macroscopic Histology Examination

Histopathologic findings associated with anaplastic thyroid cancer lesions include:

- Bulky mass (mean: 6 cm)

- Homogeneous and variegated appearance

- Light tan and fleshy with zones of necrosis and hemorrhage on cut sections

- Infiltrating, often into adjacent soft tissues and organs [11]

Microscopic Histology Examination

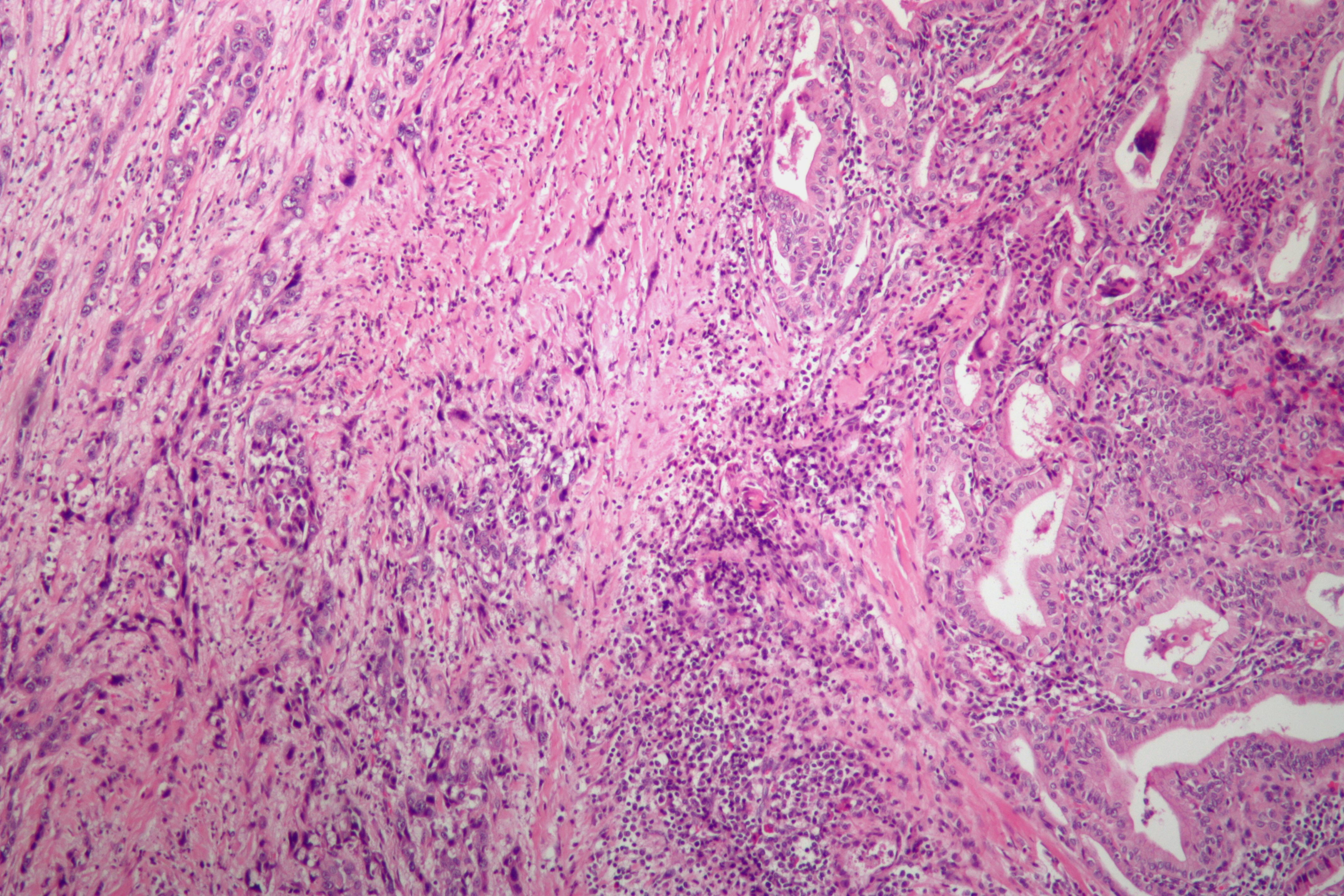

The highly variable microscopic appearances of anaplastic thyroid cancer are broadly categorized into the following 3 patterns (see Image. Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer), which can occur alone or in any combination:

- Sarcomatoid: The sarcomatoid form is malignant spindle cells with features commonly seen in high-grade pleomorphic sarcoma.

- Giant cell: The giant cell comprises highly pleomorphic malignant cells, some containing multiple nuclei.

- Epithelial: The epithelial form manifests squamoid or squamous cohesive tumor nests with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm; occasional keratinization can be present.

Necrosis, an elevated mitotic rate, and an infiltrative growth pattern are common in all 3 forms. Vascular invasion is also often present.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry helps to distinguish anaplastic carcinoma from other undifferentiated malignancies using a cluster of differentiation 45 and other lymphoid markers along with melanocytic markers to exclude lymphoma and melanoma, respectively. Common thyroid-lineage markers (eg, thyroid transcription factor-1 and thyroglobulin) are usually absent, whereas the paired box gene, also a thyroid-lineage marker, is retained in approximately half of all cases. Positive cytokeratin expression supports the epithelial nature of anaplastic thyroid cancer, but negative immunostaining for cytokeratin does not exclude the diagnosis.[12]

History and Physical

Anaplastic thyroid cancer almost invariably presents with a rapidly growing anterior neck mass, which may be causing compressive or invasive symptoms. The trachea, esophagus, and vocal cords may be involved, resulting in dysphagia, dyspnea, hoarseness, and recurrent aspiration. Additionally, 20% of patients have a history of differentiated thyroid cancer or chronic multinodular goiter.

A physical examination typically identifies a firm mass fixed to the trachea. Unlike other less invasive thyroid cancers, anaplastic thyroid cancer often invades surrounding structures, resulting in an immobile mass with swallowing on examination. While the mass is typically solid, larger lesions may have regions of fluctuance due to tumor necrosis or hemorrhage. Cervical lymph nodes should be examined as these nodes are involved in up to 40% of anaplastic thyroid cancer cases. A laryngoscopy is also important to identify and document recurrent laryngeal nerve injury.[13][14][15]

Evaluation

Diagnostic Imaging Studies

Anaplastic thyroid cancer evaluation should begin with a neck ultrasound. Findings associated with malignancy include solid masses, marked hypodensity, irregular margins, internal calcifications, wider-than-tall nodules, and cervical lymph node involvement. These features are scored using the thyroid imaging reporting and data system, predicting the probability of a malignant thyroid lesion. However, no specific findings on sonography have been established that can reliably differentiate anaplastic thyroid cancer from other thyroid malignancies.[16]

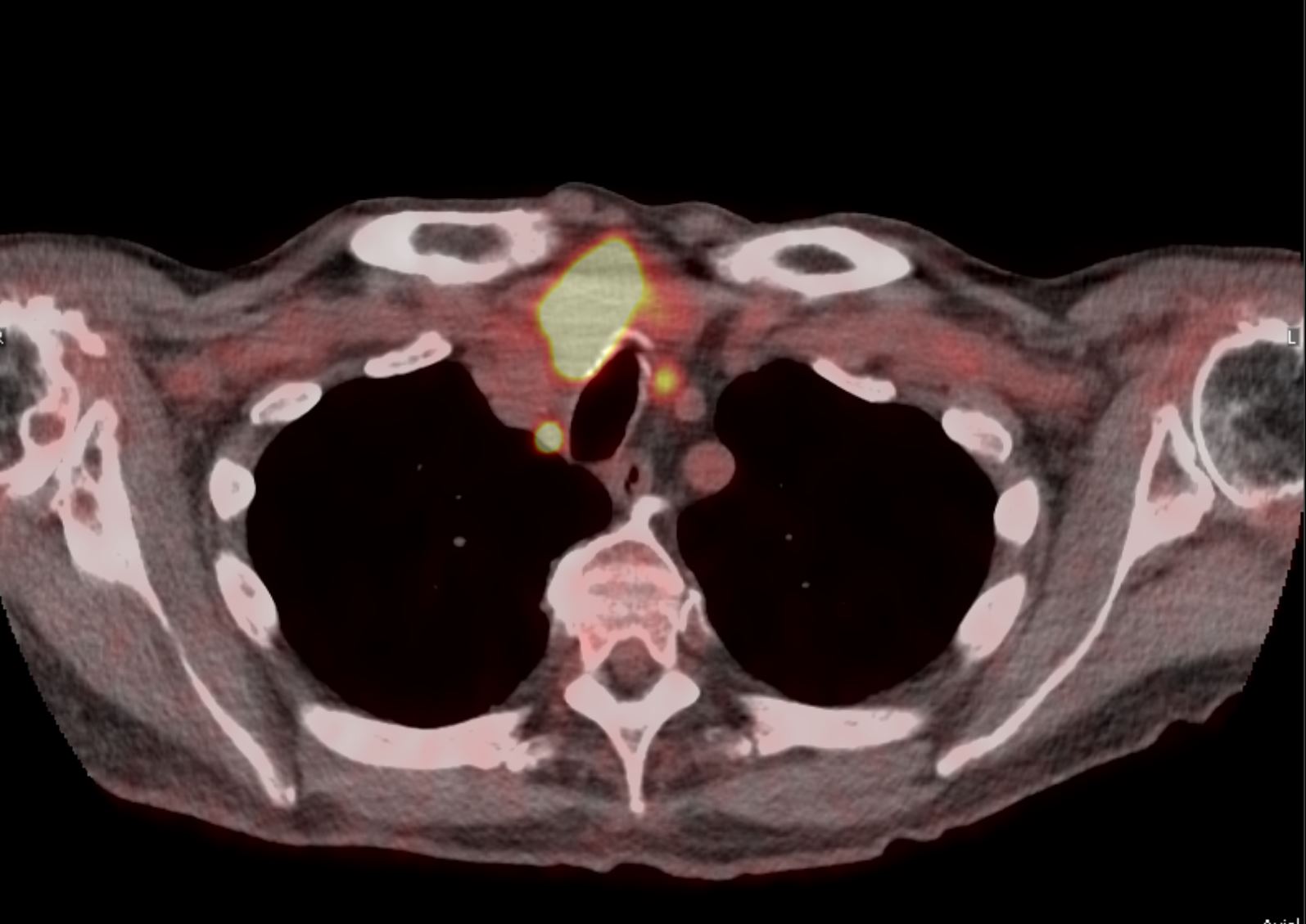

Since all anaplastic thyroid cancers are considered stage IV tumors and up to 50% will have metastatic disease at the time of presentation, all patients should be staged with a fluorodeoxyglucose F18 positron emission tomography (PET) scan or computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain, neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis. See Image. Hypermetabolic Thyroid Mass, Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography Scan (PET-CT). The lungs are the most common site of metastasis, followed by the intrathoracic and cervical lymph nodes.[17] Local invasion and the tumor's relationship to surrounding structures may be better defined with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).[18][19][20]

Biopsy Confirmation

To histologically identify a thyroid lesion, fine-needle aspiration or core needle thyroid biopsies should be performed without delay. Findings suggestive of anaplastic thyroid cancer include increased cellularity with cells and clusters with epithelioid to spindle cells, severe pleomorphism with very aberrant nuclei, high mitotic rate, and significant necrosis. Lymphocytic infiltration and acute inflammation may also be seen. In addition, perineural and vascular invasion, as well as extrathyroidal extension, frequently occur. Given the degree of abnormality, distinguishing anaplastic thyroid cancer from other high-grade tumors, including lymphomas and melanoma, may be difficult.[21]

Diagnostic Molecular Testing

BRAF status, microsatellite instability, NTRK, RET, ALK mutations, and tumor mutational burden should be assessed. In particular, BRAF mutations should be evaluated, as these mutations can change the determined treatment approaches.[22]

Laryngoscopy and Bronchoscopy

Laryngoscopy with an evaluation of the vocal cords should be performed in all patients, as recurrent laryngeal nerve invasion is prevalent at presentation. If a high suspicion of airway involvement exists, a bronchoscopy should be performed. Patients with airway involvement often require a tracheostomy for airway protection.[23]

Treatment / Management

Surgical resection is the treatment of choice for localized anaplastic thyroid cancer. Chemotherapy and radiation are used as adjuncts or as definitive therapy in patients with metastatic disease.[3] Most cases of anaplastic thyroid cancer are unresectable at presentation.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for anaplastic thyroid cancer includes:

- Metastatic disease to the thyroid, including metastatic clear-cell renal carcinoma

- Primary thyroid lymphoma

- Primary thyroid sarcoma

- Poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma

- Squamous cell thyroid carcinoma

- Medullary carcinoma [24]

Surgical Oncology

When anaplastic thyroid cancer is localized to the thyroid gland, without invasion of critical structures (eg, the trachea), complete surgical resection offers the best chance of cure. A total thyroidectomy with a therapeutic lymph node dissection is currently recommended. Adjacent structures may need to be resected en bloc if they are involved and can be sacrificed, as the ultimate goal is to obtain a negative margin. BRAF/V600E mutant anaplastic thyroid cancer can be treated with neoadjuvant dabrafenib/trametenib, especially if the tumor is borderline resectable.[11][25] Routine tracheostomy should be avoided and performed only in cases of true airway compromise.[23]

Radiation Oncology

Radiation therapy can be used in adjuvant settings and in patients with nonresectable or metastatic diseases. External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) is recommended after resection and, when combined with concurrent chemotherapy, improves overall survival. As anaplastic thyroid cancer is so aggressive and is seldom resected with negative margins, radiation with concurrent EBRT should be started as soon as possible. Using newer techniques, eg, intensity-modulated radiation therapy, improves targeting.[23] In patients with locally advanced disease, higher doses of EBRT can delay local spread and some of its devastating consequences, including airway compromise.

Medical Oncology

Cytotoxic chemotherapy alone is of limited benefit. Taxanes, doxorubicin, and cisplatin have been used with variable success. Paclitaxel, doxorubicin, and carboplatin are often used as radiosensitizing agents in administering concurrent chemoradiation. Identifying molecular targets has heralded a new therapy era, with treatments targeting specific mutations.[23] These include the following molecular targets and the respective agents:

- BRAF/V600E mutations: Dabrafenib/trametenib

- NTRK gene fusions: Larotrectinib, entrectinib, repotrectinib

- RET gene fusions: Pralsetinib, selpercatinib

Anaplastic thyroid cancer with high tumor mutational burden may respond to programmed cell death protein 1/programmed cell death ligand 1 inhibitors, including pembrolizumab and nivolumab. Neoadjuvant dabrafenib/trametinib is now a category 2B National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommendation for patients with resectable and borderline resectable tumors.[26]

Staging

Thyroid carcinoma staging is according to the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) classification. According to the International Union Against Cancer—TNM staging (primary tumor, regional lymph node involvement, and distant metastases) and AJCC system, all anaplastic thyroid cancers are considered stage IV.[3] Stage IVA and IVB patients have intrathyroidal tumors (stage IVA) and extrathyroidal tumors (stage IVB) and no distant metastatic disease, whereas stage IVC patients have distant metastasis.[23]

Prognosis

Anaplastic thyroid cancer is lethal. Historic survival estimates from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database studies report that 35% of patients have a median overall survival between 4 and 6 months.[2] More recent data incorporating patients who have received multimodality therapy, including targeted therapy, is more promising, with a median overall survival of 9.5 months. However, patients with BRAF mutant disease who received targeted therapy had a 94% survival rate at 1 year.[2] These data suggest that refinements in targeted therapy will continue to prolong survival.

Prognostic Factors

The favorable prognostic indicators of anaplastic thyroid cancer include:

Complications

Local invasion occurs in almost 70% of patients, including the muscles (65%), trachea (46%), esophagus (44%), laryngeal nerves (27%), and larynx (13%). Additionally, lymph node metastases are a feature in almost 40% of patients.[31] The progression of anaplastic thyroid cancer is rapid, and most patients die from local airway obstruction or complications of pulmonary metastases within 1 year.[11] Metastases occur in up to 75% of patients. They most frequently involve the lungs (80%), the brain (5% to13%), and bones (6% to 15%).

Deterrence and Patient Education

Anaplastic thyroid cancer is an aggressive and rapidly progressive type of thyroid gland cancer. Patients should be aware of warning signs, eg, rapid growth of a mass in the front of the neck, hoarseness, or neck pain. If these symptoms occur, immediate medical evaluation is necessary. Individuals with long-standing goiters or a history of other types of thyroid cancer should be especially vigilant for these symptoms. Surgery is the only curative treatment once diagnosed. Unfortunately, most patients have locally advanced or distant metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis, which cannot be cured.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Collaboration among healthcare professionals is essential to improve patient-centered care, safety, and outcomes in managing anaplastic thyroid cancer. Advanced clinicians bring clinical expertise to diagnose and formulate personalized treatment plans, while nurses provide direct patient care and emotional support and ensure adherence to therapies. Pharmacists play a key role in medication management, while other specialists contribute to a comprehensive approach involving surgery, radiation, and palliative care.

Effective interprofessional communication fosters teamwork, informing all clinicians of patient progress and treatment updates, which helps prevent delays. Given the disease's aggressive nature, care coordination is crucial, and ethical considerations, such as end-of-life care, ensure that treatment respects patient values. The healthcare team enhances patient safety, outcomes, and overall performance through shared decision-making and responsibility.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer. Low-power magnification microscopic examination of anaplastic thyroid cancer.

Nephron, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Simões-Pereira J, Capitão R, Limbert E, Leite V. Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer: Clinical Picture of the Last Two Decades at a Single Oncology Referral Centre and Novel Therapeutic Options. Cancers. 2019 Aug 15:11(8):. doi: 10.3390/cancers11081188. Epub 2019 Aug 15 [PubMed PMID: 31443283]

Maniakas A, Dadu R, Busaidy NL, Wang JR, Ferrarotto R, Lu C, Williams MD, Gunn GB, Hofmann MC, Cote G, Sperling J, Gross ND, Sturgis EM, Goepfert RP, Lai SY, Cabanillas ME, Zafereo M. Evaluation of Overall Survival in Patients With Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma, 2000-2019. JAMA oncology. 2020 Sep 1:6(9):1397-1404. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.3362. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32761153]

Nagaiah G, Hossain A, Mooney CJ, Parmentier J, Remick SC. Anaplastic thyroid cancer: a review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Journal of oncology. 2011:2011():542358. doi: 10.1155/2011/542358. Epub 2011 Jun 12 [PubMed PMID: 21772843]

Filetti S, Durante C, Hartl D, Leboulleux S, Locati LD, Newbold K, Papotti MG, Berruti A, ESMO Guidelines Committee. Electronic address: clinicalguidelines@esmo.org. Thyroid cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up†. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2019 Dec 1:30(12):1856-1883. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz400. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31549998]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRao SN, Smallridge RC. Anaplastic thyroid cancer: An update. Best practice & research. Clinical endocrinology & metabolism. 2023 Jan:37(1):101678. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2022.101678. Epub 2022 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 35668021]

Smallridge RC, Copland JA. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: pathogenesis and emerging therapies. Clinical oncology (Royal College of Radiologists (Great Britain)). 2010 Aug:22(6):486-97. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2010.03.013. Epub 2010 Apr 24 [PubMed PMID: 20418080]

O'Neill JP, Shaha AR. Anaplastic thyroid cancer. Oral oncology. 2013 Jul:49(7):702-6. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.03.440. Epub 2013 Apr 11 [PubMed PMID: 23583302]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceErickson LA. Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2021 Jul:96(7):2008-2011. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.05.023. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34218873]

Molinaro E, Romei C, Biagini A, Sabini E, Agate L, Mazzeo S, Materazzi G, Sellari-Franceschini S, Ribechini A, Torregrossa L, Basolo F, Vitti P, Elisei R. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: from clinicopathology to genetics and advanced therapies. Nature reviews. Endocrinology. 2017 Nov:13(11):644-660. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.76. Epub 2017 Jul 14 [PubMed PMID: 28707679]

Soares P, Lima J, Preto A, Castro P, Vinagre J, Celestino R, Couto JP, Prazeres H, Eloy C, Máximo V, Sobrinho-Simões M. Genetic alterations in poorly differentiated and undifferentiated thyroid carcinomas. Current genomics. 2011 Dec:12(8):609-17. doi: 10.2174/138920211798120853. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22654560]

Sun XS, Sun SR, Guevara N, Fakhry N, Marcy PY, Lassalle S, Peyrottes I, Bensadoun RJ, Lacout A, Santini J, Cals L, Bosset JF, Garden AS, Thariat J. Chemoradiation in anaplastic thyroid carcinomas. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2013 Jun:86(3):290-301. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2012.10.006. Epub 2012 Dec 4 [PubMed PMID: 23218594]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWalczyk A, Kopczyński J, Gąsior-Perczak D, Pałyga I, Kowalik A, Chrapek M, Hejnold M, Góźdź S, Kowalska A. Histopathology and immunohistochemistry as prognostic factors for poorly differentiated thyroid cancer in a series of Polish patients. PloS one. 2020:15(2):e0229264. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229264. Epub 2020 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 32092093]

Hadar T, Mor C, Shvero J, Levy R, Segal K. Anaplastic carcinoma of the thyroid. European journal of surgical oncology : the journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology. 1993 Dec:19(6):511-6 [PubMed PMID: 8270035]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNel CJ, van Heerden JA, Goellner JR, Gharib H, McConahey WM, Taylor WF, Grant CS. Anaplastic carcinoma of the thyroid: a clinicopathologic study of 82 cases. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 1985 Jan:60(1):51-8 [PubMed PMID: 3965822]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAin KB. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: behavior, biology, and therapeutic approaches. Thyroid : official journal of the American Thyroid Association. 1998 Aug:8(8):715-26 [PubMed PMID: 9737368]

Grant EG, Tessler FN, Hoang JK, Langer JE, Beland MD, Berland LL, Cronan JJ, Desser TS, Frates MC, Hamper UM, Middleton WD, Reading CC, Scoutt LM, Stavros AT, Teefey SA. Thyroid Ultrasound Reporting Lexicon: White Paper of the ACR Thyroid Imaging, Reporting and Data System (TIRADS) Committee. Journal of the American College of Radiology : JACR. 2015 Dec:12(12 Pt A):1272-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2015.07.011. Epub 2015 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 26419308]

Besic N, Gazic B. Sites of metastases of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: autopsy findings in 45 cases from a single institution. Thyroid : official journal of the American Thyroid Association. 2013 Jun:23(6):709-13. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0252. Epub 2013 May 28 [PubMed PMID: 23148580]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTakashima S, Morimoto S, Ikezoe J, Takai S, Kobayashi T, Koyama H, Nishiyama K, Kozuka T. CT evaluation of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 1990 May:154(5):1079-85 [PubMed PMID: 2108546]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNg TSC, Gunda V, Li R, Prytyskach M, Iwamoto Y, Kohler RH, Parangi S, Weissleder R, Miller MA. Detecting Immune Response to Therapies Targeting PDL1 and BRAF by Using Ferumoxytol MRI and Macrin in Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer. Radiology. 2021 Jan:298(1):123-132. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201791. Epub 2020 Oct 27 [PubMed PMID: 33107799]

Loh TL, Zulkiflee AB. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma mimicking thyroid abscess. AME case reports. 2018:2():20. doi: 10.21037/acr.2018.04.05. Epub 2018 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 30264016]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSuh HJ, Moon HJ, Kwak JY, Choi JS, Kim EK. Anaplastic thyroid cancer: ultrasonographic findings and the role of ultrasonography-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy. Yonsei medical journal. 2013 Nov:54(6):1400-6. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2013.54.6.1400. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24142644]

Nylén C, Mechera R, Maréchal-Ross I, Tsang V, Chou A, Gill AJ, Clifton-Bligh RJ, Robinson BG, Sywak MS, Sidhu SB, Glover AR. Molecular Markers Guiding Thyroid Cancer Management. Cancers. 2020 Aug 4:12(8):. doi: 10.3390/cancers12082164. Epub 2020 Aug 4 [PubMed PMID: 32759760]

Haddad RI, Bischoff L, Ball D, Bernet V, Blomain E, Busaidy NL, Campbell M, Dickson P, Duh QY, Ehya H, Goldner WS, Guo T, Haymart M, Holt S, Hunt JP, Iagaru A, Kandeel F, Lamonica DM, Mandel S, Markovina S, McIver B, Raeburn CD, Rezaee R, Ridge JA, Roth MY, Scheri RP, Shah JP, Sipos JA, Sippel R, Sturgeon C, Wang TN, Wirth LJ, Wong RJ, Yeh M, Cassara CJ, Darlow S. Thyroid Carcinoma, Version 2.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2022 Aug:20(8):925-951. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2022.0040. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35948029]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSilver JA, Roy CF, Lai JK, Caglar D, Kost K. Metastatic Clear Renal-Cell Carcinoma Mimicking Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer: A Case Report. Ear, nose, & throat journal. 2024 Jul:103(7):NP407-NP410. doi: 10.1177/01455613211065512. Epub 2021 Dec 13 [PubMed PMID: 34903079]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHaigh PI, Ituarte PH, Wu HS, Treseler PA, Posner MD, Quivey JM, Duh QY, Clark OH. Completely resected anaplastic thyroid carcinoma combined with adjuvant chemotherapy and irradiation is associated with prolonged survival. Cancer. 2001 Jun 15:91(12):2335-42 [PubMed PMID: 11413523]

Maniakas A, Zafereo M, Cabanillas ME. Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer: New Horizons and Challenges. Endocrinology and metabolism clinics of North America. 2022 Jun:51(2):391-401. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2021.11.020. Epub 2022 May 4 [PubMed PMID: 35662448]

Besic N, Hocevar M, Zgajnar J, Pogacnik A, Grazio-Frkovic S, Auersperg M. Prognostic factors in anaplastic carcinoma of the thyroid-a multivariate survival analysis of 188 patients. Langenbeck's archives of surgery. 2005 Jun:390(3):203-8 [PubMed PMID: 15599758]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSugitani I, Miyauchi A, Sugino K, Okamoto T, Yoshida A, Suzuki S. Prognostic factors and treatment outcomes for anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: ATC Research Consortium of Japan cohort study of 677 patients. World journal of surgery. 2012 Jun:36(6):1247-54. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1437-z. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22311136]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYau T, Lo CY, Epstein RJ, Lam AK, Wan KY, Lang BH. Treatment outcomes in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: survival improvement in young patients with localized disease treated by combination of surgery and radiotherapy. Annals of surgical oncology. 2008 Sep:15(9):2500-5. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0005-0. Epub 2008 Jun 26 [PubMed PMID: 18581185]

Kim TY, Kim KW, Jung TS, Kim JM, Kim SW, Chung KW, Kim EY, Gong G, Oh YL, Cho SY, Yi KH, Kim WB, Park DJ, Chung JH, Cho BY, Shong YK. Prognostic factors for Korean patients with anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Head & neck. 2007 Aug:29(8):765-72 [PubMed PMID: 17274052]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePolistena A, Monacelli M, Lucchini R, Triola R, Conti C, Avenia S, Rondelli F, Bugiantella W, Barillaro I, Sanguinetti A, Avenia N. The role of surgery in the treatment of thyroid anaplastic carcinoma in the elderly. International journal of surgery (London, England). 2014:12 Suppl 2():S170-S176. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.08.347. Epub 2014 Aug 26 [PubMed PMID: 25167852]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence