Introduction

Shoulder pain is a common clinical complaint with an annual incidence of 14.7 per 1000 patients per year.[1] Lifetime prevalence has reportedly been as high as 70%.[2] Rotator cuff pathology, acromioclavicular, and glenohumeral joint disorders constitute the most common causes of shoulder pain.[3] The shoulder can also be a site of inflammatory conditions. Intra-articular steroid injection for management of adhesive capsulitis is well studied and an important cornerstone of management for patients with this disorder.[4][5][6]

Shoulder joint injection can be with or without image guidance. Image-guided shoulder arthrography is a technique that was first described in 1933 by Oberholzer.[3] Schneider et al. described a simplified straight vertical approach with the aid of fluoroscopy that is the most common procedure performed today.[3]

The important aspects of a fluroscopic guided shoulder joint injection include:

- Minimizing patient discomfort.

- Maintaining patient safety.

- Maintaining proper needle technique to enter the rotator cuff interval or the acromioclavicular joint.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Four joints make up the shoulder girdle. These include the sternoclavicular, acromioclavicular, scapulothoracic, and glenohumeral joints. The glenohumeral joint is a partial ball-and-socket joint with an articulation of the humeral head with the glenoid cavity.[7] The glenohumeral joint contains a loose joint capsule. The relatively large surface of the humeral head respective to the glenoid makes it an extremely mobile joint.[8] The stability of the glenohumeral joint is complex and includes static and dynamic restraints. Example of static restraints includes the glenoid labrum and glenohumeral ligaments. Examples of dynamic restraints include rotator cuff muscles and the long head of the biceps tendon.

The acromioclavicular (AC) joint serves as the articulation between the lateral end of the clavicle and the acromion of the scapula. Etiologies for acromioclavicular joint osteoarthritis include degenerative and post-traumatic causes and, to a lesser frequency, septic and inflammatory etiologies.[9] Symptomatic pain can occur with overhead activity. Clinical management involves physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and intraarticular injections. If symptoms persist, operative resection of the distal clavicle can be a consideration.[10]

Indications

Clinicians often consider joint injection as a therapeutic modality after attempting other interventions. Initial measures primarily include physical therapy and NSAIDs. The primary indications for glenohumeral joint injection include osteoarthritis and adhesive capsulitis. Fluoroscopic assisted injection of contrast material into the glenohumeral articulation is also useful for CT or MR arthrography. Similarly, the primary indications for therapeutic acromioclavicular joint injection include osteoarthritis and post-traumatic osteolysis of the distal clavicle.

Contraindications

Absolute contraindications include, but are not limited to:

- Septic arthritis

- Cellulitis at or near the skin entrance of the injection needle

- Bacteremia

- Acute fracture

- Anaphylaxis/allergy to injected therapeutic agents

Equipment

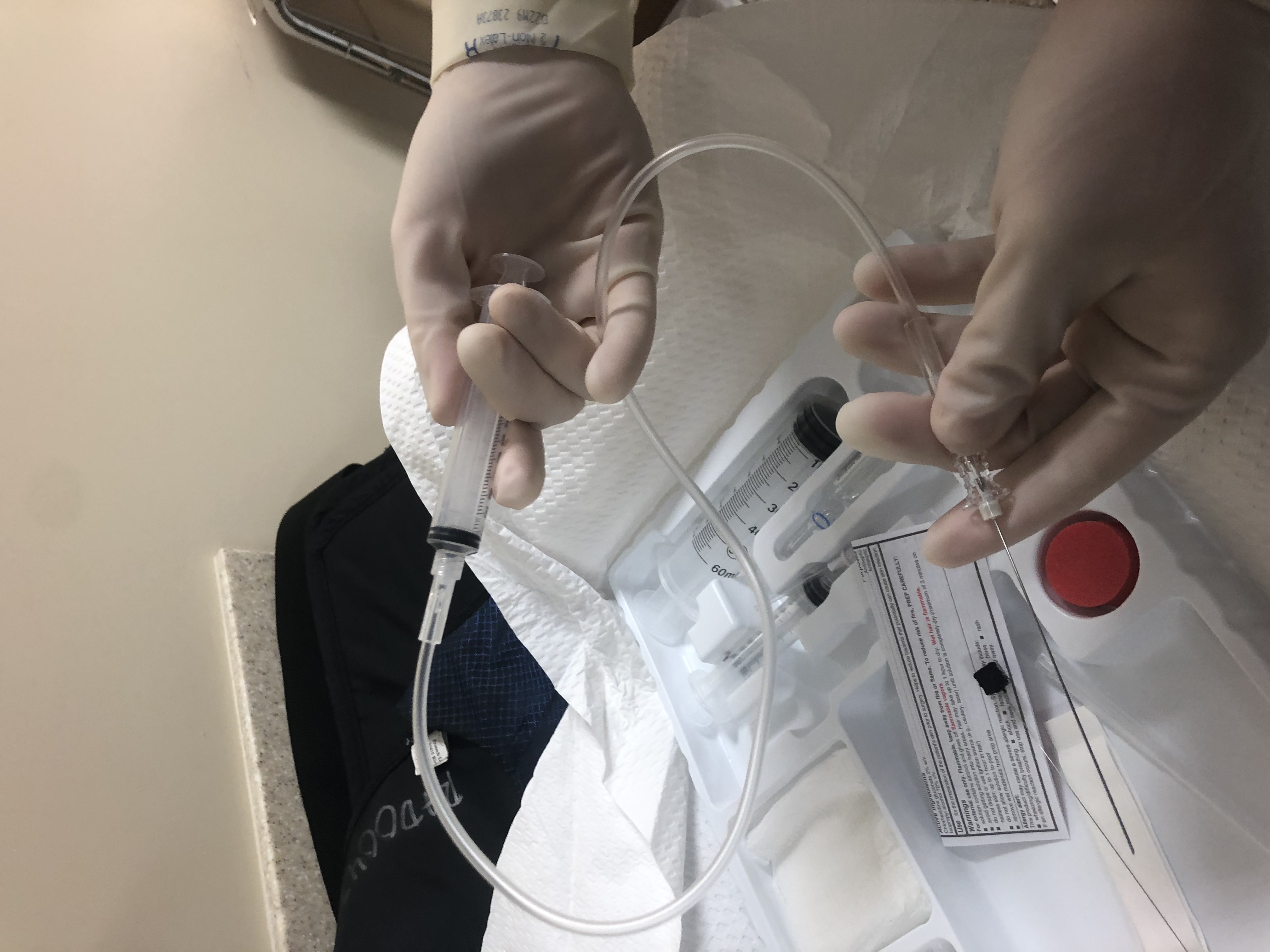

Equipment, including needle gauge, and pharmacotherapeutic mixtures, vary institutionally and can be operator-specific. The following list includes a brief overview of possible equipment used for the described procedure.

Glenohumeral joint injection:

- Fenestrated drape or towel drapes

- Fluoroscopy machine

- 1 milliliter (mL) to 3 mL of 1% lidocaine hydrochloride for local anesthesia

- 23-gauge spinal needle

- 2 to 4 mL of iodinated contrast

- 1mL of 40 mg/mL triamcinolone and 1 mL of 0.2% ropivacaine (if performing a therapeutic injection)

- 10 mL of 0.5% gadolinium (if performing MR arthrography)

Acromioclavicular joint injection:

- Fenestrated drape or towel drapes

- Fluoroscopy machine

- 1 mL to 3 mL of 1% lidocaine hydrochloride for local anesthesia

- 23-gauge needle

- Mixture of 0.5 mL of triamcinolone solution (40 mg/ml) and 0.5 mL of 1% lidocaine

Personnel

Personnel includes:

- Clinician performing the injection

- Radiology technologist trained in using the fluoroscopy machine

An MRI technologist and a radiologist are potentially indirectly involved if the glenohumeral joint is injected for purposes of an MR arthrogram.

Preparation

A thorough discussion with a patient before the procedure includes the following:

- A detailed explanation of the procedure

- The potential level of discomfort/pain

- A comprehensive evaluation of the skin entry site

- Prior medical conditions or surgeries that might affect the procedure, to include joint prosthesis

- Potential diagnoses resulting from the procedure

- Possible complications of the procedure

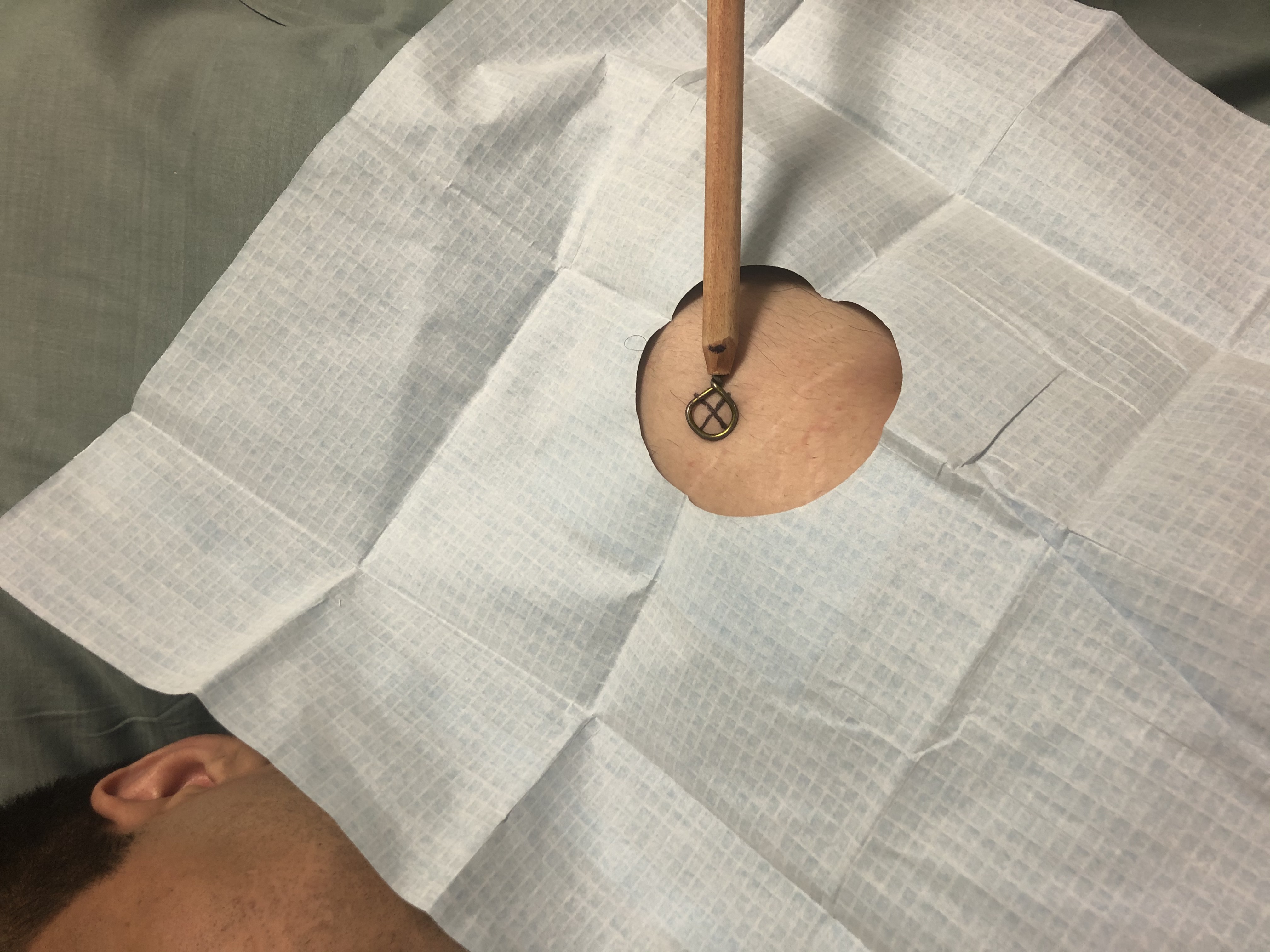

Prior to beginning the fluoroscopic procedure, all involved personnel must don appropriate lead aprons. The patient is placed in a comfortable supine position. The patient's arm is placed in external rotation with the palm of the hand up. A small weight can be placed on the patient's palm to maintain this position throughout the procedure. A brief fluoroscopic image is obtained with a metallic marker stick overlying the superomedial quadrant of the humeral head immediately lateral to the humeral head cortex. This approach also allows the operator to visualize the proposed needle skin trajectory. The skin is then marked at the proposed site of entry. The skin site is prepared via standard sterile technique.

If the acromioclavicular joint is being accessed, the metallic marker stick serves to localize the acromioclavicular joint capsule, and the overlying skin is marked. The skin site is prepared via standard sterile technique.

Technique or Treatment

After the skin is marked, the local subcutaneous soft tissues are anesthetized with 1 to 3 mL of 1% lidocaine hydrochloride for local anesthesia. A 23-gauge 3.5-inch spinal needle is then used with a stylet in place with an anterior/vertical approach through the soft tissues until reaching the humeral head cortex.

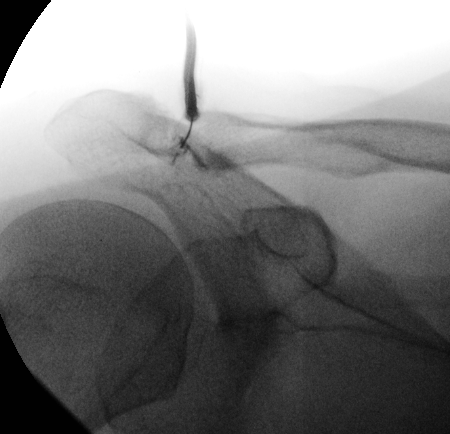

Intermittent fluoroscopy allows for careful centering of the needle hub over the needle tip to ensure a precise perpendicular approach into the joint space. The needle is slightly retracted to avoid immediate termination within the humeral head hyaline cartilage. The stylet is removed, and a small volume of anesthetic is then injected to ensure a low-pressure intra-articular placement and anesthetization of the cortical surface. A test contrast injection with approximately 0.5 to 2 mL of contrast ensures that the needle does not terminate within an adjacent bursa and is truly intra-articular. Intra-articular contrast movement, as evidenced by a small column of contrast between the glenoid and humerus, confirms intra-articular placement for imaging documentation. A syringe containing the corticosteroid with or without a connecting tube is then attached to the 23-gauge needle, and the steroid is subsequently injected into the joint. In the case of an MR arthrogram, the syringe contains approximately 10 mL of diluted gadolinium, and approximately 8 to 10 mL is injected into the glenohumeral joint.

If the acromioclavicular joint is being injected, the local soft tissues are similarly anesthetized with lidocaine. A needle is advanced in a similar vertical approach until the joint capsule is penetrated. A small volume of contrast confirms the intracapsular position of the needle via fluoroscopy. This verification is followed by an injection of approximately a 1 mL mixture of a 0.5 mL triamcinolone (40 mg/mL) and a 0.5 mL lidocaine solution.

Complications

Complications are rare and include:

- Exacerbation of baseline pain

- Allergic reaction

- Small vessel injury

- Septic arthropathy

Clinical Significance

Shoulder pain remains one of the most common outpatient musculoskeletal complaints with a prevalence of between 7% and 26% at any one time.[11] Shoulder pain and related dysfunction have a significant impact on the quality of life. Underlying inflammation from osteoarthrosis related to aging and trauma usually underlies the pathogenesis of acute and chronic pain of the glenohumeral and acromioclavicular joints. Nonoperative modalities to include physical therapy, NSAIDs, and steroid injection have been the cornerstone of shoulder pain treatment. Different studies have focused on comparing the benefit of steroid injections compared to NSAIDs. Results have been variable with a few notable meta-analysis studies demonstrating the superiority of steroid injection to NSAIDs.[12][13] These studies have also shown the short term efficacy of intra-articular steroid injections.

Amongst the different clinical indications for a steroid injection, the particular usefulness of its application in the treatment of adhesive capsulitis is important. Adhesive capsulitis or so-called "frozen shoulder" is a self-limiting clinical entity with a benign and self-resolving course.[14][15] The periodic use of therapeutic steroid injections for short term relief of pain associated with adhesive capsulitis has been a particular strength in the application of steroid injection, especially since adhesive capsulitis has three stages, each of which may last months.

Fluoroscopic guidance for injections described in this article helps in avoiding critical structures of the shoulder girdle with enhanced needle guidance through the rotator cuff interval. Image guidance helps avoid the labrum, long head of the biceps tendon, the subscapularis tendon, and the supraspinatus tendon. Thus, potential morbidity associated with the procedure without image guidance is avoidable.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The role of a radiology technologist is exceptionally important in helping the operator during the procedure. Patient comfort is critical in properly performing the procedure as significant patient movement can affect satisfactory targeting through the rotator cuff interval. Movement can also affect needle trajectory with an injury of the subscapularis, supraspinatus, or biceps tendon. The technologist plays an important role in assisting in fluoroscopic image acquisition. Documentation of immediate pain relief is important for the referring provider, as this can help manage treatment.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

van der Windt DA, Koes BW, de Jong BA, Bouter LM. Shoulder disorders in general practice: incidence, patient characteristics, and management. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 1995 Dec:54(12):959-64 [PubMed PMID: 8546527]

Luime JJ, Koes BW, Hendriksen IJ, Burdorf A, Verhagen AP, Miedema HS, Verhaar JA. Prevalence and incidence of shoulder pain in the general population; a systematic review. Scandinavian journal of rheumatology. 2004:33(2):73-81 [PubMed PMID: 15163107]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMitchell C, Adebajo A, Hay E, Carr A. Shoulder pain: diagnosis and management in primary care. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2005 Nov 12:331(7525):1124-8 [PubMed PMID: 16282408]

Carette S, Moffet H, Tardif J, Bessette L, Morin F, Frémont P, Bykerk V, Thorne C, Bell M, Bensen W, Blanchette C. Intraarticular corticosteroids, supervised physiotherapy, or a combination of the two in the treatment of adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: a placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2003 Mar:48(3):829-38 [PubMed PMID: 12632439]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRyans I, Montgomery A, Galway R, Kernohan WG, McKane R. A randomized controlled trial of intra-articular triamcinolone and/or physiotherapy in shoulder capsulitis. Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 2005 Apr:44(4):529-35 [PubMed PMID: 15657070]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKoh KH. Corticosteroid injection for adhesive capsulitis in primary care: a systematic review of randomised clinical trials. Singapore medical journal. 2016 Dec:57(12):646-657. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2016146. Epub 2016 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 27570870]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMiniato MA, Anand P, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Shoulder. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725618]

Chang LR, Anand P, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Glenohumeral Joint. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725703]

Hyland S, Charlick M, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Clavicle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30252246]

Menge TJ, Boykin RE, Bushnell BD, Byram IR. Acromioclavicular osteoarthritis: a common cause of shoulder pain. Southern medical journal. 2014 May:107(5):324-9. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0000000000000101. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24937735]

van den Dolder PA, Ferreira PH, Refshauge KM. Effectiveness of soft tissue massage and exercise for the treatment of non-specific shoulder pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. British journal of sports medicine. 2014 Aug:48(16):1216-26. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090553. Epub 2012 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 22844035]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceZheng XQ, Li K, Wei YD, Tie HT, Yi XY, Huang W. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs versus corticosteroid for treatment of shoulder pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2014 Oct:95(10):1824-31. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.04.024. Epub 2014 May 16 [PubMed PMID: 24841629]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSun Y, Chen J, Li H, Jiang J, Chen S. Steroid Injection and Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Agents for Shoulder Pain: A PRISMA Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Medicine. 2015 Dec:94(50):e2216. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002216. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26683932]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSchultheis A, Reichwein F, Nebelung W. [Frozen shoulder syndrome]. MMW Fortschritte der Medizin. 2009 Jul 23:151(30-33):36-7 [PubMed PMID: 19722459]

Schultheis A, Reichwein F, Nebelung W. [Frozen shoulder. Diagnosis and therapy]. Der Orthopade. 2008 Nov:37(11):1065-6, 1068-72. doi: 10.1007/s00132-008-1305-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18825364]