Introduction

Alpha-adrenergic agonist toxicity is due to a broad group of pharmaceutical agents known as alpha agonists, which can be further broken down into central alpha-2 agonists and peripheral alpha-1 agonists. Central alpha-2 agonists include clonidine, guanfacine, tizanidine, guanabenz, and methyldopa. Peripheral alpha-1 agonists include imidazoline, oxymetazoline, tetrahydrozoline, and naphazoline. Mainly there are 2 alpha receptors of pharmacological significance – central alpha-2 and peripheral alpha-1 adrenergic receptors. Stimulation of central alpha-2 receptors causes decreased secretion of catecholamines through a negative feedback mechanism. Stimulation of peripheral alpha-1 receptors primarily increases blood pressure via induced vasoconstriction. Alpha-adrenergic agonist toxicity is of primary concern with alpha-2 adrenergic agonist xenobiotics through the resulting depletion of catecholamines associated with these agents; however, there are many topical alpha-1 agonists that when misused cause similar toxicity. Toxicity is encountered in various populations, particularly in children and adolescents, due to the growing use of these agents. Toxicity is associated with a compilation of symptoms, including central nervous system depression, bradycardia, and hypotension. Alpha-adrenergic toxicity is often very responsive to supportive care, including intravenous fluid administration, airway monitoring, and repletion of catecholamines as necessary via the use of vasopressor agents. There is no antidote approved for human use, and naloxone has no proven efficacy.[1][2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Alpha-agonist toxicity may occur accidentally or intentionally. Toxicity is often due to intentional overdose and accidental pediatric ingestion. Overdoses can occur after ingestion of pills, skin patches, or via self-administered medication pumps that may be misused or malfunctioning. Chronic and accidental overdose can occur in situations involving chronic pain, with use of oral extended-release and transdermal formularies. Pharmacy dosing and compounding errors have also occurred, which is of particular concern for pediatric toxicity. In addition, drug-drug interactions may occur.[3][4][5]

Epidemiology

Alpha-2 agonists are prescribed for multiple indications in a variety of patient populations causing common toxicity in patients of different ages with different backgrounds and comorbidities. Clonidine is often prescribed to adults for treating hypertension, opioid withdrawal, and adjunctively to pediatric patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). It is used to directly treat ADHD and adjunctively for those who are on stimulant medications, as evidence exists that it enhances REM sleep patterns at night. Guanfacine is often prescribed for the same indications and is often used in the pediatric population. Tizanidine, another alpha-2 agonist, is prescribed for muscle relaxation in conditions involving spasticity, such as multiple sclerosis. Other central alpha-2 agonists, such as oxymetazoline, tetrahydrozoline, and naphazoline are generally used as over-the-counter topical agents intended for nasal or ophthalmic vasoconstrictive purposes due to their peripheral alpha-1 stimulatory properties; however, when ingested, also can cause alpha-2 agonism. These medications can lend themselves to improper use, abuse, and intentional and accidental overdose. In addition, children can be of significant risk of exposure due to inadvertent ingestions of any of these medications, as well as due to pharmacy dosing and compounding errors. Despite the vast exposure to numerous populations, the rising use of these agents to treat ADHD and other behavioral disorders lends to increased risk, and particularly salient is self-harm attempts among adolescents.

Pathophysiology

Alpha-adrenergic agonists stimulate central or peripheral alpha receptors, resulting in different pharmacological action. Mainly there are two alpha receptors of pharmacological significance – central alpha-2 and peripheral alpha-1 adrenergic receptors. The primary mechanism of action of alpha-2 agonists is stimulation of presynaptic alpha-2receptors in the central nervous system, activating inhibitory neurons which lead to a reduction in sympathetic output via a negative feedback mechanism. This causes an overall decrease in the secretion of the catecholamine, norepinephrine, which is beneficial for the desired therapeutic effects of decreased blood pressure and heart rate. Peripheral alpha-1 agonists are meant to induce vasoconstriction, whether administered topically or systemically. Systemically, phenylephrine is used as a vasopressor, whereas as oxymetazoline, for example, is used as a nasal decongestant by way of vasoconstriction on the nasal mucosa. Alpha agonists may lose selectivity for targeted receptor when ingested or misused. There are also peripheral alpha-2 receptors that, when stimulated, cause catecholamine release.

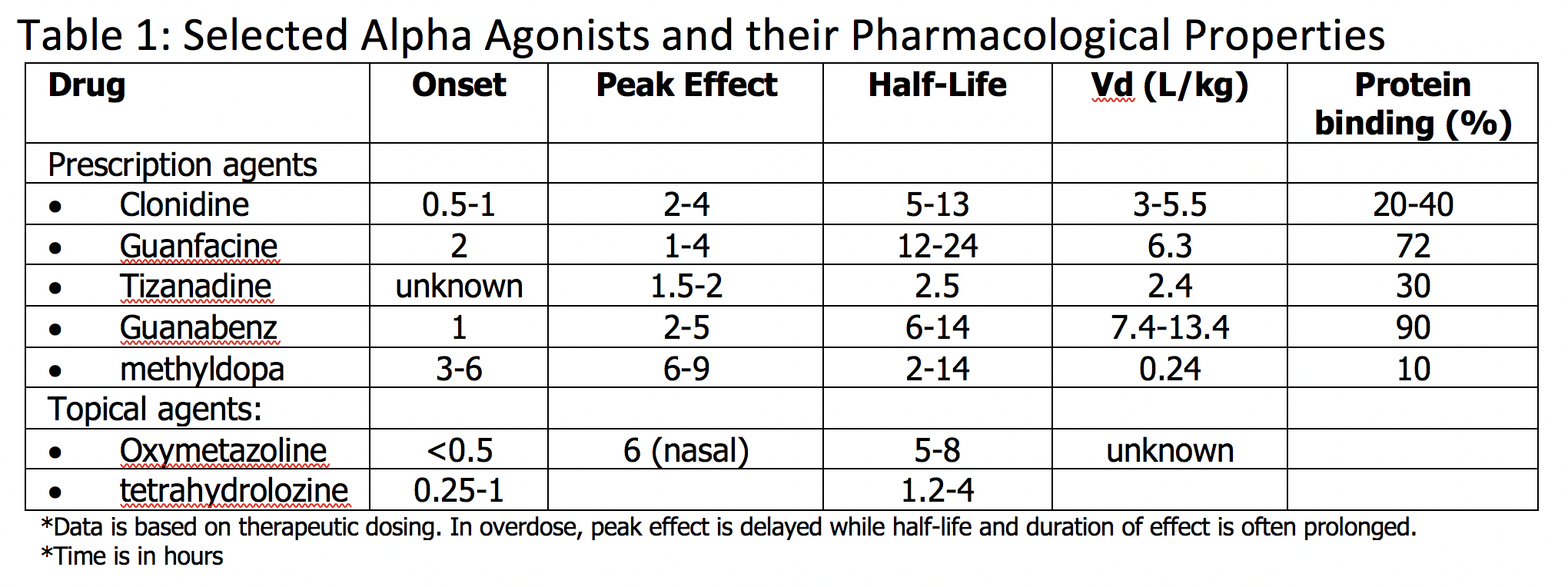

Toxicokinetics

The primary mechanism of toxicity of alpha agonists is through central alpha-2 agonism. Central alpha-2 agonist toxicity may occur from an acute or nonacute overdose of central alpha-2 agonists or misuse of topical alpha-1 agonists, which when ingested, stimulate alpha-2 receptors. In overdose, an overall depletion of catecholamines occurs, leading to central nervous system depression, along with bradycardia and hypotension. Other clinical findings can include miosis, hypothermia, and possible respiratory depression. Paradoxically, in overdose, there is also transient stimulation of peripheral alpha-1 receptors and post-synaptic alpha-2 receptors, causing brief catecholamine release, which leads to an early, transient hypertension. Symptomatology is not necessarily dose-dependent. In children, clonidine toxicity has occurred with as low as 0.1 mg ingested. The onset of symptoms usually occurs within 30 to 60 minutes, although peak effects can occur more than 6 to 12 hours after ingestion. Overall, symptoms can be expected for 12 to 36 hours.

History and Physical

Alpha-2 agonist toxicity results from decreased catecholamine output, which leads to sympathetic depression. Associated symptoms most commonly include central nervous system depression, bradycardia, and hypotension. Miosis and hyporeflexia are often evident. In more severe cases, symptomatology may also include coma, hypothermia, respiratory depression or apnea. Patients may present with normal vital signs and mental status early on, but symptoms generally ensue within the first hour, with evidence of somnolence, bradycardia and hypotension – sometimes preceded by transient hypertension. Deterioration of clinical course can occur with further decrease in mental status, progressing from somnolence to coma, worsened bradycardia and hypotension, and occasionally hypothermia and respiratory depression in severe cases. This latter compilation of symptoms may occur as the initial presentation when time of ingestion to reaching medical care is delayed.

Evaluation

The diagnosis of alpha agonist toxicity is clinical. Central alpha agonists are not detectable in standard urine drug screen, and specific drug concentrations are not routinely available. Concentrations can be obtained through specialized laboratories but are usually not indicated and involve a send-out process which can take days to weeks for results. As with all toxic patients, particularly when an overdose is of concern, evaluation should include a detailed history and physical exam. Airway, breathing, circulation and glycemic status should immediately be evaluated. History should include attention to medication and prescription access, possible discussion with family members and friends, a local, physician, drug-monitoring program inquiry, and review of prior presentations. A physical exam should include close attention to vital signs, including temperature, heart rate, and respiration rate and depth (i.e., minute ventilation and tidal volume) to identify bradypnea and hypopnea. A thorough neurological exam should also be done. All toxicology patients should also have an electrocardiogram, basic metabolic panel, and an acetaminophen concentration. Other considerations are salicylate concentration, transaminases, and pregnancy status. Neuroimaging should be considered if other possible traumatic or medical etiologies are contributing to the presentation. A chest x-ray should be considered if aspiration is of concern.

Treatment / Management

Asymptomatic patients who are at risk for alpha-agonist toxicity can be given activated charcoal and monitored. Activated charcoal may be useful in decreasing absorption and can be considered early in the presentation, provided patient is protecting his or her airway and is not somnolent. If asymptomatic after 4 hours, patients can be toxicologically cleared as these agents, except for methyldopa, have a fast onset of action. Symptomatic patients should usually be admitted to the intensive care unit. Symptoms can be prolonged beyond several days. Supportive care is the mainstay of treatment for alpha-2 agonist toxicity, including airway management and cardiac monitoring. Intubation may be necessary. There is no proven benefit to gastric emptying, and enhanced elimination with dialysis is not useful. There is no specific antidote approved for human use. Although naloxone has been reported to reverse symptoms, it is not a proven antidote, nor is it considered the standard of care. It is not routinely recommended but can be trialed if attempting to distinguish from possible opioid toxicity. Early hypertension often resolves before the presentation, but if observed, should not be treated as it is transient. Treatment of early hypertension may cause worsening of the eventual hypotension. Alpha-2 agonist toxicity is often very responsive to treatment, and initial treatment should include tactile stimulation and intravenous fluid administration. Persistent bradycardia and hypotension are responsive to vasopressor administration, which serves to replace the deficiency of catecholamines. Usually, only low dose vasopressor administration is required for reversal of symptoms, and initial vasopressor of choice is norepinephrine. Fatalities are exceedingly rare, and patients can be considered toxicologically cleared when they are clinically well with the return of baseline vital signs and mental status.

Differential Diagnosis

Considering the clinical picture of alpha-2 agonist toxicity, the differential diagnosis includes other drugs and medical conditions that cause CNS depression, bradycardia, and hypotension. Drug toxicities that should be considered in the differential diagnosis should include beta adrenergic antagonists, calcium channel antagonists, cardiac glycosides, and possibly GABA-B agonists such as baclofen. Alpha-2 agonist toxicity can also include miosis, or “pinpoint pupils,” and respiratory depression, which can strongly resemble an opioid overdose. Toxicity secondary to alpha-2 agonists should be considered in patients that present with apparent opioid toxicity who do not respond to naloxone administration. Medical conditions in the differential diagnosis should include neurogenic shock and acute myocardial infarctions involving the sinoatrial node or the atrioventricular node.

Prognosis

Full recovery usually occurs within 24 hours with adequate supportive care.

Complications

Perfusion must be maintained. If adequate perfusion is not maintained, the patient may be at risk for end-organ damage, including myocardial ischemia and anoxic brain injury.

Consultations

As with any toxic scenario, management should be in conjunction with the advice of a medical toxicologist.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Parents should be educated regarding the risks of alpha agonists, whether in over-the-counter or prescription formularies. Prescribers should be cognizant when prescribing alpha agonists, especially to at-risk pediatric patients.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Alpha agonist toxicity can be associated with severe morbidity and mortality, but with proper management, patients usually do very well. Consultation with a medical toxicologist is advised.

- Central alpha-2 agonist toxicity is associated with CNS depression, bradycardia, hypotension, and miosis.

- The pediatric population is at particular risk due to the prevalence of central alpha-2 agonist prescriptions for children and teens with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

- There is no specific antidote. Naloxone is not a proven antidote.

- Patients are very easily treated with intravenous fluids and if needed, vasopressors. Norepinephrine is the vasopressor of choice.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Healthcare workers and nurse practitioners who encounter patients with alpha-agonist toxicity in the emergency department should follow the Trauma ABCDE protocol for patient management. If the condition is not treated, it can be associated with severe morbidity and mortality. Consultation with a medical toxicologist is advised. Even though there is no specific antidote, proper management leads to good outcomes.

- Asymptomatic patients who are at risk for alpha-agonist toxicity can be given activated charcoal and monitored by the nursing staff, with any changes in the patient's condition reported to the clinician (MD, DO, PA, or NP).

- If the patient requires admission, the nursing staff will need to assist with supportive care including airway management and cardiac monitoring.

- The emergency pharmacist should assist in medication reconciliation and evaluate for drug-drug interaction. If a low dose of a vasopressor is needed, the pharmacist should assist in appropriate dosing of norepinephrine.

The interprofessional team of nurses, pharmacists, and clinicians should communicate with and educate the family to assist them in understanding the patient's condition. If this was a deliberate overdose, education will include evaluation of the underlying causes which often involves the family. The best outcomes are achieved by an interprofessional team approach. [Level V]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Hill J, Alford DP. Prescription Medication Misuse. Seminars in neurology. 2018 Dec:38(6):654-664. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1673691. Epub 2018 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 30522141]

Zabkowski T, Saracyn M. Drug adherence and drug-related problems in pharmacotherapy for lower urinary tract symptoms related to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Journal of physiology and pharmacology : an official journal of the Polish Physiological Society. 2018 Aug:69(4):. doi: 10.26402/jpp.2018.4.14. Epub 2018 Dec 9 [PubMed PMID: 30552307]

Cibickova L, Caran T, Dobias M, Ondra P, Vorisek V, Cibicek N. Multi-drug intoxication fatality involving atorvastatin: A case report. Forensic science international. 2015 Dec:257():e26-e31. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2015.09.020. Epub 2015 Oct 13 [PubMed PMID: 26508377]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKoseoglu Z, Kara B, Satar S. Bradycardia and hypotension in mianserin intoxication. Human & experimental toxicology. 2010 Oct:29(10):887-8. doi: 10.1177/0960327110364639. Epub 2010 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 20203131]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceThorsteinsson A, Johannesdottir A, Eiríksson H, Helgason H. Severe labetalol overdose in an 8-month-old infant. Paediatric anaesthesia. 2008 May:18(5):435-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2008.02501.x. Epub 2008 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 18312512]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence