Introduction

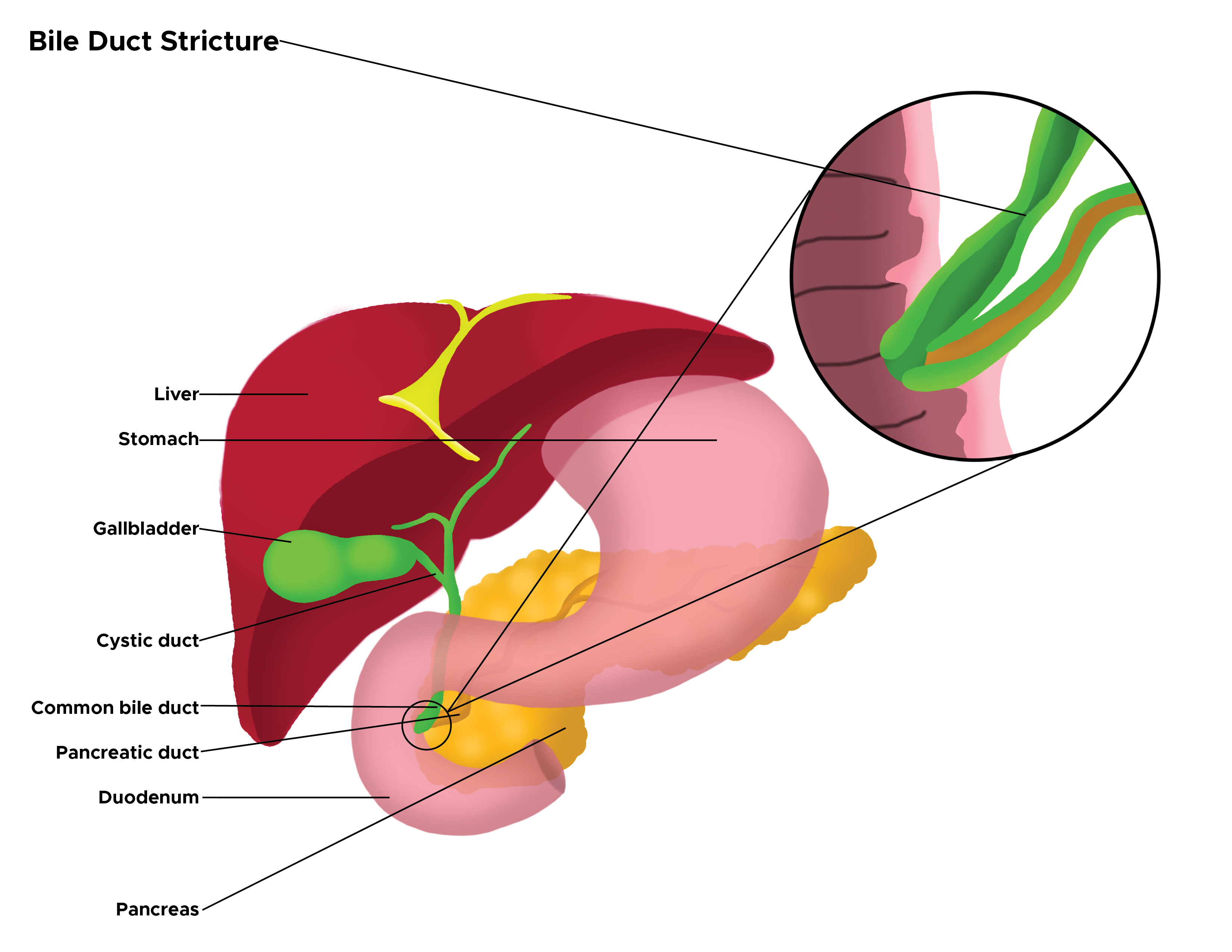

Biliary strictures or bile duct strictures refer to segments of the intrahepatic or extrahepatic biliary ductal system narrowing. When narrowed, they impede the normal antegrade flow of bile, causing proximal dilatation resulting in clinical and pathological sequelae of biliary obstruction. Patients with chronic biliary strictures present a unique challenge when malignancy is suspected. Diagnosing and managing patients with biliary strictures potentially encompasses an interprofessional approach, including endoscopists, surgeons, interventional radiologists, and hepatobiliary specialists.[1][2][3] See Image. Illustration of Bile Duct Stricture.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Bile duct strictures can be congenital or acquired.[4] The latter is more common than congenital strictures. Acquired strictures are further classified as either benign or malignant.[5] A wide range of benign acquired conditions cause bile duct strictures, contributing to 30% of biliary strictures.[6] This includes iatrogenic strictures, which comprise the majority of benign biliary strictures. Misidentification of the biliary duct for cystic duct during laparoscopic cholecystectomy leads to bile duct injury, which may be partial or complete. The long-term sequelae of these injuries lead to the formation of benign biliary strictures.[7] The incidence of injury may be decreased by obtaining an intraoperative cholangiogram, especially in cases of gangrenous cholecystitis or empyema of the gallbladder.[8][9] Understanding the anatomy of the blood supply to the bile duct is paramount to its repair.[10] Similarly, anastomotic biliary strictures are a known complication after orthotopic liver transplantation.[11] Anastomotic strictures are also known to occur after a Whipple procedure (incidence of 4%) performed for pancreatic mass or trauma. This is especially true for small-caliber thin-walled ducts.[1] Though relatively rare, strictures can also result from infections like tuberculosis.[12] Other benign causes are listed below:

- Chronic pancreatitis

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Acute cholangitis

- Blunt and penetrating abdominal trauma

- Autoimmune diseases (pancreatitis or cholangitis)

- Mirizzi syndrome

- Ischemic cholangiopathy

- Biliary inflammatory pseudotumors

- Oriental cholangiohepatitis (Ascaris lumbricoides and Clonorchis sinensis)

- Post radiation

However, the most common etiology for biliary strictures is malignancies.[13] Both pancreatic head cancer and cholangiocarcinoma are attributed to the majority of malignant biliary strictures. Others include periampullary cancer, gallbladder carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, lymphoma, and metastasis to regional solid organs and lymph nodes.[6][14][6][15]

Epidemiology

Globally, the incidence of biliary strictures is thought to be on the rise primarily because of the iatrogenic bile duct injuries resulting from the widespread practice of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Multiple strategies, like the critical view of safety, have been suggested to minimize bile duct injuries and associated morbidity from bile leaks and strictures.[16] The estimated rate of biliary injuries is about 0.7% after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Most of these injuries are minor injuries or bile leaks. Biliary strictures are rare in the pediatric age group.[17] There is no published difference in the incidence or prevalence of biliary strictures in males as compared to females, though some risk factors, like alcoholic chronic pancreatitis, are more typical in males.

Pathophysiology

Biliary strictures are characterized by narrowing a bile duct segment associated with proximal ductal dilatation. Obstruction of bile flow leads to elevation of serum bilirubin levels with clinical and laboratory features of obstructive jaundice. Stasis of bile is a major risk factor for ascending cholangitis.[18] Radical resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) shows that benign strictures have tapered margins with smooth and symmetric borders. On the other hand, malignant strictures have shouldering of the margins with irregular and asymmetric borders.[11] Malignant strictures involve a long segment instead of benign, which involves shorter segments. Malignant strictures appear to enhance contrast-enhanced cross-sectional imaging.[18] The strictures can be classified according to the Strasberg-Bismuth classification. Classification helps in guiding management.[18][19][20]

Type E injuries lead to strictures of the hepatic ducts, further defined by the proximal extent.

- E1: Common hepatic duct division greater than 2 cm from the bifurcation.

- E2: Common hepatic duct division less than 2 cm from the bifurcation.

- E3: Common bile duct division at the bifurcation.

- E4: Hilar stricture involves confluence and loss of communication between the right and left hepatic ducts.

- E5: Involves aberrant right hepatic duct with concomitant stricture of the common hepatic duct.[14]

Histopathology

Generally, histopathological findings in biliary strictures depend on the etiological agent or mechanism. For example, in the case of primary sclerosing cholangitis, histopathology reveals intrahepatic or extrahepatic bile duct inflammation and fibro-obliteration.[5] In assessing biliary strictures, histological appraisal with cytology or histopathology is primarily required to rule out malignancy.[18] However, if imaging has confirmed or has a high suspicion for malignancy, a positive histological diagnosis is not mandatory preoperatively.

History and Physical

The clinical presentation depends on the location and cause of the stricture.[11] Biliary strictures can be asymptomatic with non-contributory findings on physical examination. Nevertheless, a section of patients with biliary strictures present with obstructive jaundice features, including yellowing of mucosal surfaces and skin, pruritus, pale stools, steatorrhoea, and dark urine.[19] Constitutional symptoms, such as weight loss, fever, nausea, vomiting, and malaise may accompany these. Patients may present with an acute abdomen secondary to cholangitis or hepatic abscess, which can result as a complication of the bile duct stricture.[21] A history of fever and leukocytosis suggests an infective cause or sequelae to the strictures. History of weight loss, abdominal or back pain, and worsening performance status should be taken with caution since it could warn towards a possible malignant etiology.[15] The previous history of hepatobiliary surgery, autoimmune disease, pancreatitis, cholelithiasis, or chemotherapy should be elicited as it can be pivotal in determining or eliminating the differential diagnosis.[11] Further efforts should be made during the physical examination to elicit specific clinical signs like Murphy and Courvoisier signs, as this may also help narrow the diagnosis or etiology of jaundice. The presence of hard masses in the abdomen may point toward an advanced malignant process.

Evaluation

Contributory laboratory findings are mainly drawn from a liver function test, a coagulation profile, and a complete blood count. Liver function tests may reveal elevated levels of conjugated bilirubin and liver enzymes (alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl transferase). Transaminases may be elevated nonspecifically. Immunological studies may be obtained to assess certain autoimmune etiologies of biliary strictures. Apt diagnosis and further management are based on the correlation of laboratory data and imaging findings with epidemiologic and clinical data.[11]

Deranged liver function tests and coagulation profiles may help to determine the algorithm of subsequent imaging and minimally invasive studies.[15][22] Likewise, when present, certain immunological markers help in accurate diagnosis and management. For example, IgG4-associated sclerosing cholangitis presents as hilar or distal common bile duct strictures associated with autoimmune pancreatitis (IgG4-related). Both these disease entities are responsive to steroid therapy.[6][11] Antinuclear antibodies and rheumatoid arthritis factors may help support this diagnosis.

Assay of CA19-9 and carcinoembryonic antigen can be obtained in patients with suspected hepatobiliary malignancy as they can help with diagnosis and follow-up. Of note, these are not specific to biliary malignancy. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology is highly sensitive and specific but not useful in ruling out malignancy.[6]

Ductal dilatation is a major feature of imaging for biliary strictures.[1] Imaging of suspected biliary strictures can begin with a trans-abdominal ultrasound, which detects biliary dilatation and is highly sensitive for detecting biliary obstruction and the level of obstruction. However, it has a low yield for the detection of strictures. Malignant biliary strictures are more likely to cause severe ductal dilation than benign ones.[6][11] Endoscopic ultrasound has high sensitivity and accuracy for malignant lesions and has been used as the imaging test of choice in assessing distal biliary obstruction.

Computed tomography (CT) scan has higher sensitivity than trans-abdominal ultrasound for biliary malignancy, and its utility can be improved with the use of a multi-detector CT scan and CT-pancreatic protocol in providing more information on tumor vascular encroachment and biliary tree obstruction. It can also detect complications from biliary obstruction, such as cholangitis and abscesses.[1]

MRCP can provide high-quality cholangiograms, thus establishing the location and extent of biliary strictures. It provides a cross-sectional and 3-dimensional reconstruction of the biliary tree.[5] It helps guide endoscopic therapy, especially if ERCP is contraindicated. MRCP also does not have ionizing radiation, thus making it a superior option over a multi-detector CT scan. However, its sensitivity and specificity (which can be improved by diffusion-weighted imaging, DWI) are comparable to that of ERCP.[1][5]

Evaluating biliary strictures by ERCP can determine etiology, provide tissue samples for cytology and histology, and facilitate therapeutic interventions like stenting obstructed segments from strictures. However, it is associated with post-ERCP pancreatitis and is being overtaken by newer technologies like confocal laser endomicroscopy. Other emerging technologies useful in assessing the etiology of biliary strictures include fluorescent in-situ hybridization, direct peroral cholangioscopy, and intraductal ultrasound.[5][13][23]

A hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid scan helps to identify the level of bile leaks and bile injuries after cholecystectomy.[14]

Treatment / Management

Medical management of biliary strictures is largely restricted to addressing complications from biliary obstructions and sometimes treating the causative agent. Therefore, analgesics, empiric antibiotics, hemodynamic support with intravenous fluids with or without vasopressors, and inotropes are often instituted where applicable.[24] Also common are therapies aimed at reducing the effects of increasing bilirubinemia. These efforts are often supportive and in preparation for definitive therapy.[25] Other forms of medical treatment could be aimed at the prevention of further complications like excessive bleeding due to a coagulopathy as well as deep vein thrombosis and sepsis in the early postoperative period.

The goal of the interventions for biliary strictures includes reestablishing patency and avoiding additional procedures.[11][19] There are varying options for operative or interventional management. These options can be accomplished via endoscopy, open surgery, or percutaneously. The stricture's etiology and location, as well as the patient’s hemodynamic stability and nutritional status, could determine the timing and type of intervention required.[25] The Bismuth classification can further guide the most appropriate approach since it offers a guide to determining the level at which healthy biliary tissue is available for repair and anastomosis.[11] Likewise, the Strasberg classification system, which incorporates the presence of a bile leak and lateral injuries into consideration, can also be useful in some cases in choosing the best intervention.[19] Additionally, preoperative determination of malignancy is pivotal in the planning of treatment and avoiding undue exploratory surgery.

In general, endoscopic treatment is the first line of treatment for biliary strictures.[26] The treatment of biliary strictures includes options shown below

Common Interventions for Biliary Strictures

Dilatation

- The preferred approach for the management of benign biliary stricture[11]

- Balloon dilatation is used extensively for strictures resulting from primary sclerosing cholangitis[5]

- Commonly performed endoscopically

- Tracts resulting from percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage can be used for access during dilatation[27] (B3)

Stenting

- Commonly performed endoscopically

- Useful in the management of both benign and malignant common bile duct strictures[2]

- Used to reduce hyperbilirubinemia or cholangitis in patients before definitive surgery[22]

- Useful for palliation in inoperable malignant strictures (B3)

Resection and Anastomosis

- The decision depends on whether it’s a malignant or benign stricture and whether the desired outcome is palliative or curative[25]

- Associated with significant morbidity and cost[6]

Bypass

- Hepaticojejunostomy may make it difficult in the future to perform ERCP[25]

- Bypass may involve choledochoduodenostomy in certain cases

An image-guided percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage catheter may be placed to palliate hyperbilirubinemia in patients with either inoperable disease or until completion of neoadjuvant therapy. A biliary sphincterotomy involves the division of the biliary sphincter of Oddi and the intraduodenal segment of the common bile duct. It enables the removal of stones and the placement of stents and assists endoscopic access for future ERCP. It also facilitates balloon dilatation.[18] Novel techniques for managing biliary strictures include magnetic compression anastomosis, intraductal radiofrequency ablation, and biodegradable stents.[18] Others include large bore catheterization, cutting-balloon dilation, and placement of retrievable covered stents.[19] The magnetic compression anastomosis has specifically been used for biliary recanalization with favorable results.[3]

Differential Diagnosis

In diagnosing and managing biliary strictures, the most valuable and critical distinction that should be made is between benign and malignant etiology. This differentiation presents a major diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Therefore, elaborate history taking, physical examination, and diagnostic workup should be completed.[13] Other techniques like fluorescence in situ hybridization, Kras/p53 mutation analysis, intraductal biopsies, and confocal laser endomicroscopy may be considered to improve the diagnostic yield.[6] A diagnosis of choledocholithiasis should also be considered in cases of suspected biliary strictures.

Prognosis

The mortality in patients with biliary structures depends on the underlying etiology. Biliary strictures due to chronic pancreatitis, trauma, radiation, or operative injury have a good prognosis. Still, those resulting from malignant and primary sclerosing cholangitis may have unfavorable prognoses as well as strictures arising in patients with HIV cholangiopathy.

Complications

Biliary strictures can get complicated by chronic low-grade biliary obstruction. The complications include:

- Recurrent cholangitis

- Ascending cholangitis

- Gram-negative septicemia

- Stone formation

- Hepatic abscesses

- Secondary biliary cirrhosis

- End-stage liver disease

- Cholangiocarcinoma[11]

Other complications could result from interventional procedures, and these may include:

Consultations

Biliary strictures frequently present a challenge in terms of diagnosis, necessitating interdisciplinary collaboration. Likewise, patients with benign strictures may have a protracted, complicated course calling for multiple consultations. Therefore, teams caring for patients with biliary strictures may comprise:

- Hepatobiliary surgeons

- Medical oncologists

- Diagnostic radiologists

- Surgical oncologists

- Endoscopists

- Gastroenterologists

- Interventional radiologists[15]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients drinking alcohol should be counseled against the practice, especially those whose diagnosis is linked to drinking, ie alcoholic chronic pancreatitis. Patients who have biliary stents placed should be educated about the recognition of symptoms and signs of blocked stents. Those with external drains should be taught how to flush their drains using aseptic measures. Lastly, the patient and their caregivers should be informed about the prognosis of their disease.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Bile duct strictures may present with nonspecific signs and symptoms of obstructive jaundice, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fever, and leukocytosis. The cause of bile duct strictures may be 1 of myriads of possible diagnoses, including benign and malignant etiologies. The complexity of this disease process lies in the challenges of its diagnosis and subsequent appropriate management. Inaccurate diagnosis or delay in management can have devastating outcomes for the patient. While the general surgeon is almost always involved in the care of these patients, it may become imperative to consult with an interprofessional team of specialists that includes gastroenterologists, interventional radiologists, hepatobiliary surgeons, surgical oncologists, and transplant surgeons.

The Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons offers guidelines for the clinical application of laparoscopic biliary tract surgery. Regarding common bile duct injuries, the guidelines suggest that the factors that have been associated with bile duct injury include surgeon experience, patient age, male sex, and acute cholecystitis. If major bile duct injuries occur, outcomes are improved by early recognition and immediate referral to experienced hepatobiliary specialists for further treatment before any repair is attempted by the primary surgeon unless the primary surgeon has significant experience in biliary reconstruction. Nurses play a vital role during the recovery of such patients. They monitor the patient closely for changes in vital signs and mental status as the patients recuperate. The nurses help in the timely recognition of common postoperative complications such as deep vein thrombosis and anastomotic leaks. The role of the laboratory personnel and pharmacist is critical as well. The pharmacist may be involved in managing parenteral nutrition for critically ill patients.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Israr S, Rubalcava NS, Weinberg JA, Jones M, Gillespie TL. Management of Biliary Stricture Following Emergent Pancreaticoduodenectomy for Trauma: Report of Two Cases. Cureus. 2018 Jun 18:10(6):e2829. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2829. Epub 2018 Jun 18 [PubMed PMID: 30131922]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFerm S, Fisher C, Hassam A, Rubin M, Kim SH, Hussain SA. Primary Endoscopic Closure of Duodenal Perforation Secondary to Biliary Stent Migration: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Journal of investigative medicine high impact case reports. 2018 Jan-Dec:6():2324709618792031. doi: 10.1177/2324709618792031. Epub 2018 Aug 2 [PubMed PMID: 30116760]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLiu XM, Yan XP, Zhang HK, Ma F, Guo YG, Fan C, Wang SP, Shi AH, Wang B, Wang HH, Li JH, Zhang XG, Wu R, Zhang XF, Lv Y. Magnetic Anastomosis for Biliojejunostomy: First Prospective Clinical Trial. World journal of surgery. 2018 Dec:42(12):4039-4045. doi: 10.1007/s00268-018-4710-y. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29947988]

Narayan KS, Kumar M, Padhi S, Jain M, Ashdhir P, Pokharna RK. Tubercular biliary hilar stricture: A rare case report. The Indian journal of tuberculosis. 2018 Jul:65(3):266-267. doi: 10.1016/j.ijtb.2017.06.013. Epub 2017 Aug 12 [PubMed PMID: 29933873]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTabibian JH, Baron TH. Endoscopic management of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Expert review of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2018 Jul:12(7):693-703. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2018.1483719. Epub 2018 Jun 18 [PubMed PMID: 29883229]

Singh A, Gelrud A, Agarwal B. Biliary strictures: diagnostic considerations and approach. Gastroenterology report. 2015 Feb:3(1):22-31. doi: 10.1093/gastro/gou072. Epub 2014 Oct 28 [PubMed PMID: 25355800]

Moghul F, Kashyap S. Bile Duct Injury. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31536309]

Kowalski A, Kashyap S, Mathew G, Pfeifer C. Clostridial Cholecystitis. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28846291]

Kashyap S, Mathew G, King KC. Gallbladder Empyema. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083646]

Seeras K, Qasawa RN, Kashyap S, Kalani AD. Bile Duct Repair. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30252245]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceShanbhogue AK, Tirumani SH, Prasad SR, Fasih N, McInnes M. Benign biliary strictures: a current comprehensive clinical and imaging review. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2011 Aug:197(2):W295-306. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.6002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21785056]

Chadha VK, Bhalla BB, Ramesh SB, Gupta J, Nagendra N, Padmesh R, Ahmed J, Srivastava RK, Jaiswal RK, Praseeja P. Tuberculosis diagnostic and treatment practices in private sector: Implementation study in an Indian city. The Indian journal of tuberculosis. 2018 Oct:65(4):315-321. doi: 10.1016/j.ijtb.2018.06.010. Epub 2018 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 30522619]

Paranandi B, Oppong KW. Biliary strictures: endoscopic assessment and management. Frontline gastroenterology. 2017 Apr:8(2):133-137. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2016-100773. Epub 2017 Feb 10 [PubMed PMID: 28261440]

Strasberg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 1995 Jan:180(1):101-25 [PubMed PMID: 8000648]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLorenz JM. Management of Malignant Biliary Obstruction. Seminars in interventional radiology. 2016 Dec:33(4):259-267 [PubMed PMID: 27904244]

Gupta V, Jain G. Safe laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Adoption of universal culture of safety in cholecystectomy. World journal of gastrointestinal surgery. 2019 Feb 27:11(2):62-84. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v11.i2.62. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30842813]

Chapoy PR, Kendall RS, Fonkalsrud E, Ament ME. Congenital stricture of the common hepatic duct: an unusual case without jaundice. Gastroenterology. 1981 Feb:80(2):380-3 [PubMed PMID: 7450427]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMa MX, Jayasekeran V, Chong AK. Benign biliary strictures: prevalence, impact, and management strategies. Clinical and experimental gastroenterology. 2019:12():83-92. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S165016. Epub 2019 Feb 18 [PubMed PMID: 30858721]

Kapoor BS, Mauri G, Lorenz JM. Management of Biliary Strictures: State-of-the-Art Review. Radiology. 2018 Dec:289(3):590-603. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018172424. Epub 2018 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 30351249]

Chun K. Recent classifications of the common bile duct injury. Korean journal of hepato-biliary-pancreatic surgery. 2014 Aug:18(3):69-72. doi: 10.14701/kjhbps.2014.18.3.69. Epub 2014 Aug 31 [PubMed PMID: 26155253]

Patterson JW, Kashyap S, Dominique E. Acute Abdomen. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083722]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePu LZ, Singh R, Loong CK, de Moura EG. Malignant Biliary Obstruction: Evidence for Best Practice. Gastroenterology research and practice. 2016:2016():3296801. doi: 10.1155/2016/3296801. Epub 2016 Feb 11 [PubMed PMID: 26981114]

Costamagna G, Boškoski I. Current treatment of benign biliary strictures. Annals of gastroenterology. 2013:26(1):37-40 [PubMed PMID: 24714594]

Dadhwal US, Kumar V. Benign bile duct strictures. Medical journal, Armed Forces India. 2012 Jul:68(3):299-303. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2012.04.014. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24532893]

Kukar M, Wilkinson N. Surgical Management of Bile Duct Strictures. The Indian journal of surgery. 2015 Apr:77(2):125-32. doi: 10.1007/s12262-013-0972-7. Epub 2013 Sep 20 [PubMed PMID: 26139967]

Wong MYW, Kaffes AJ. Benign Biliary Strictures: Narrowing the Differences Between Endoscopic and Surgical Treatments. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2018 Oct:63(10):2495-2496. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5212-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30054841]

Inui K, Yoshino J, Miyoshi H. Differential diagnosis and treatment of biliary strictures. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2009 Nov:7(11 Suppl):S79-83. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.08.027. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19896104]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence