Introduction

Platelets are the smallest blood cells, typically around 2 μm in diameter and anucleated, with an average lifespan of 7 to 10 days in humans.[1][2] Platelets first gained recognition as having a role in hemostasis more than 100 years ago by the Italian pathologist Giulio Bizzozero, and significant progress was made in elucidating their role in hemostasis and thrombosis during the 20th century using light microscopy techniques.[3] More recently, advanced techniques such as electron microscopy and immunofluorescence have allowed far more detailed analysis of platelet ultrastructure and function.

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

Platelets play a key role in hemostasis, and their dysfunction can result in a variety of inherited and acquired bleeding disorders. They also have involvement in the development of thrombi in the context of atherosclerosis, a pathological process associated with significant morbidity and mortality, primarily through myocardial infarction and stroke.

Structure

Platelets form by the fragmentation of megakaryocytes within the bone marrow. Megakaryocytes duplicate in the marrow without dividing, resulting in the production of giant cells. Within these giant cells, organelles organize into discrete domains, which will eventually become individual platelets, separated by a network of invaginating plasma membranes. These megakaryocytes are positioned next to the sinusoidal walls so that shearing forces from circulating blood fragment the megakaryocyte cytoplasm into individual platelets and sweep these new platelets into the bloodstream.[1] Platelets circulate in the blood in discoid form but undergo significant structural changes following activation, mediated by actin and myosin within the cytoplasm. The platelets transform from discoid forms into compact spheres with dendritic extensions, which allow platelet adhesion. A variety of membrane-bound glycoprotein receptors facilitates adhesion and aggregation of platelets.[1]

As described above, platelets are anuclear but do contain ribonucleic acid, ribosomes, mitochondria, and various granules, which are important in enacting platelet function.[2] There are three distinct types of platelet granule

- α-granules: the most abundant and largest secretory granules, containing most of the platelet factors involved in hemostasis, including p-selectin, von Willebrand Factor, and fibrinogen [4]

- Dense granules: the smallest granules, which are visible on electron microscopy as dense bodies and contain adenosine diphosphate and serotonin, as well as high levels of calcium

- Lysosomes: contain hydrolytic enzymes, including acid phosphatase and arylsulfatase [5]

An ‘open canalicular system’ formed of deep surface membrane invaginations facilitates the secretion of granules.[1] This system also has a key role in the transport of membrane receptors, allowing them to cluster, stabilize platelet adhesion sites, and amplify signaling.[2]

Function

Platelets have a crucial role in thrombus formation and hemostasis. Platelets circulate in the blood in a quiescent discoid form but may become activated by contact with damaged blood vessel walls. Following blood vessel damage, substances in the exposed subendothelial extracellular matrix, such as collagen and von Willebrand factor, may bind to platelet surface receptors.[6] Platelets will adhere to sites of injury, and receptor binding will lead to platelet activation.

As described above, platelets undergo a structural transformation at this point and begin to secrete granule contents to promote platelet aggregation and platelet plug formation. Activated platelets release factors such as ADP, thromboxane A2, and thrombin, which can promote the activation of other nearby platelets in a positive feedback mechanism.[7] Activation also leads to the surface expression of glycoprotein IIb-IIIa. This protein binds to fibrinogen, allowing cross-linking of platelets and mediating platelet aggregation.[1] A final change during activation is the expression of phosphatidylserine, which generates a negative charge on platelet surfaces. This negative charge allows clotting factor complexes to assemble on the surface as part of the secondary hemostasis response.[2]

The above processes ultimately lead to the production of a thrombus: a structure formed of aggregated, activated platelets combined with a mesh of cross-linked fibrin and entrapped erythrocytes and leukocytes. This thrombus restores the structural integrity of the damaged vessel wall and prevents blood loss while the vessel heals. There is additional growing evidence of the role of platelets in inflammatory and immune responses. Leukocytes are recruited to thrombi via interactions with platelet P-selectin, and platelet α-granules contain a range of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Antiplatelet medications have been found to affect immunity and may even reduce mortality related to infection and sepsis.[8]

Tissue Preparation

Platelets are most commonly visualized via a peripheral blood film. Blood can either be taken directly from a finger prick or a venous sample stored in an anticoagulant blood bottle. The blood smear requires preparation without excessive delay following obtaining the sample, as delay can lead to clumping of platelets and pseudothrombocytopenia. Blood should be smeared thinly onto a slide to produce a monolayer of cells and allowed to dry. Once dry, the smear should be fixed with alcohol and stained.[9]

For functional platelet studies, washed platelet suspensions are often necessary. Platelets are sequentially centrifuged and resuspended in a buffer solution (Tyrode’s albumin buffer) to isolate them from the plasma and clotting factors that normally surround them. This process allows examination of the intrinsic properties of the platelets in a controlled suspension rather than of the interaction between platelets and their natural plasma environment.[3]

Histochemistry and Cytochemistry

Romanowsky stains, such as Wright-Giemsa are typically used in blood films to produce differential staining of blood components, with platelets staining blue.[10] The platelet color and granular appearance on light microscopy are a result of the α-granules, which are azurophilic and comprise about 10% of the total platelet volume.[4][11] Disorders that lead to a reduction in the number of azurophilic α-granules result in the pale-looking cells of “gray platelet syndrome.”[11] Other stains may be needed to differentiate between different structures even when carrying out detailed electron microscopy assessment. The electron density of lysosomes and α-granules are very similar, but tests for the presence of lysosomal enzymes, such as acid phosphatase staining and arylsulfatase localization, can differentiate the 2.[12]

Microscopy, Light

Quantitative platelet disorders (ie, thrombocytopenia and thrombocytosis) are readily diagnosable using light microscopy, while qualitative disorders are more difficult, especially given the small size of typical platelets. Though platelets are too small for detailed assessment via light microscopy, some basic evaluations are possible in terms of size and morphology. Large platelets are usually the result of megakaryocyte hyperactivity. Younger (larger) reticulated platelets can be produced more quickly and so might be seen in conditions where there is increased demand for platelet production. Large platelets are also present in some inherited conditions, where platelets as big as a typical red blood cell may be visible.[9]

In the diagnosis of suspected inherited platelet disorders, diagnostic protocols have undergone development, which involves initial assessment via traditional blood film with light microscopy, followed by more specific testing guided by the blood film findings. For example, if a blood film demonstrates large platelets, targeted immunofluorescence testing may be carried out against glycoprotein Ib (absence of which may indicate a diagnosis of Bernard-Soulier syndrome) or filamin 1A (absence of which may indicate filamin A-related thrombocytopenia). Normal-sized platelets can be tested for surface GPIIb/IIIa, which is lacking in Glanzmann thrombasthenia. β1-tubulin can also be visualized via immunofluorescence in small platelets, with abnormal bent forms of the protein indicating Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome or X-linked thrombocytopenia.[11]

Microscopy, Electron

Electron microscopy can provide a detailed assessment of platelet ultrastructure and is important in the diagnosis of various platelet disorders. Three separate platelet ultrastructural compartments can be described on electron microscopy: cytoplasmic granules, platelet membranes, and the cytoskeleton.[13] Platelet ultrastructure and function are described above, and it is clear that abnormalities in any of these three functional compartments may result in abnormal function (thrombocytopathy). Electron microscopy can visualize these structures and identify many of these abnormalities.

“Grey platelet syndrome” may be suspected based on reduced staining on initial light microscopy, but electron microscopy can reveal an absence of α-granules and the presence of empty α-granule-sized vacuoles. Bernard-Soulier syndrome results from a defect in the GPIb/V/IX receptor, and when examined under electron microscopy, a variety of abnormalities may present, such as giant cell size, dilated surface-connected canalicular system, disorganized microtubules, and reduced granule numbers. MYH9-related disorders result in platelets with a similar giant size but otherwise normal ultrastructure on electron microscopy.[13]

Pathophysiology

Because of platelets’ essential role in hemostasis, platelet pathology correlates with excessive bleeding. Patients with thrombocytopenia or reduced platelet function tend to present with petechiae and mucocutaneous bleeding. Following small endothelial lesions, primary hemostasis is often ineffective, and so bleeding, such as epistaxis, gingival bleeding, and purpura occur. Patients with coagulation disorders such as Haemophilia, on the other hand, tend not to experience excessive bleeding from small cuts but struggle to control larger bleeds where fibrin reinforcement of the primary clot is required.[1]

Platelet abnormalities are categorized into quantitative disorders (thrombocytopenia or thrombocytosis) and qualitative disorders (thrombasthenias). Thrombocytopenia is common and usually acquired. Common causes include hypersplenism, drugs (e.g., heparin-induced thrombocytopenia), infections, pregnancy, and immune thrombocytopenia. Hereditary thrombocytopenias are rare but merit consideration, especially if giant platelets are visible on the blood film.[1] Thrombocytosis is also common, with 88 to 97% of cases attributed as reactive in origin and the remainder being clonal disorders and spurious results.[14] A wide variety of thrombasthenias have been identified, with some examples provided above. Platelets are also involved in the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis. They play an obvious role in thrombus formation on the surface of a ruptured plaque in response to the exposure of subendothelial structures. Platelets also appear to be involved in the recruitment of leukocytes to plaques during their formation through cytokine release and receptor-ligand interactions.[15]

Clinical Significance

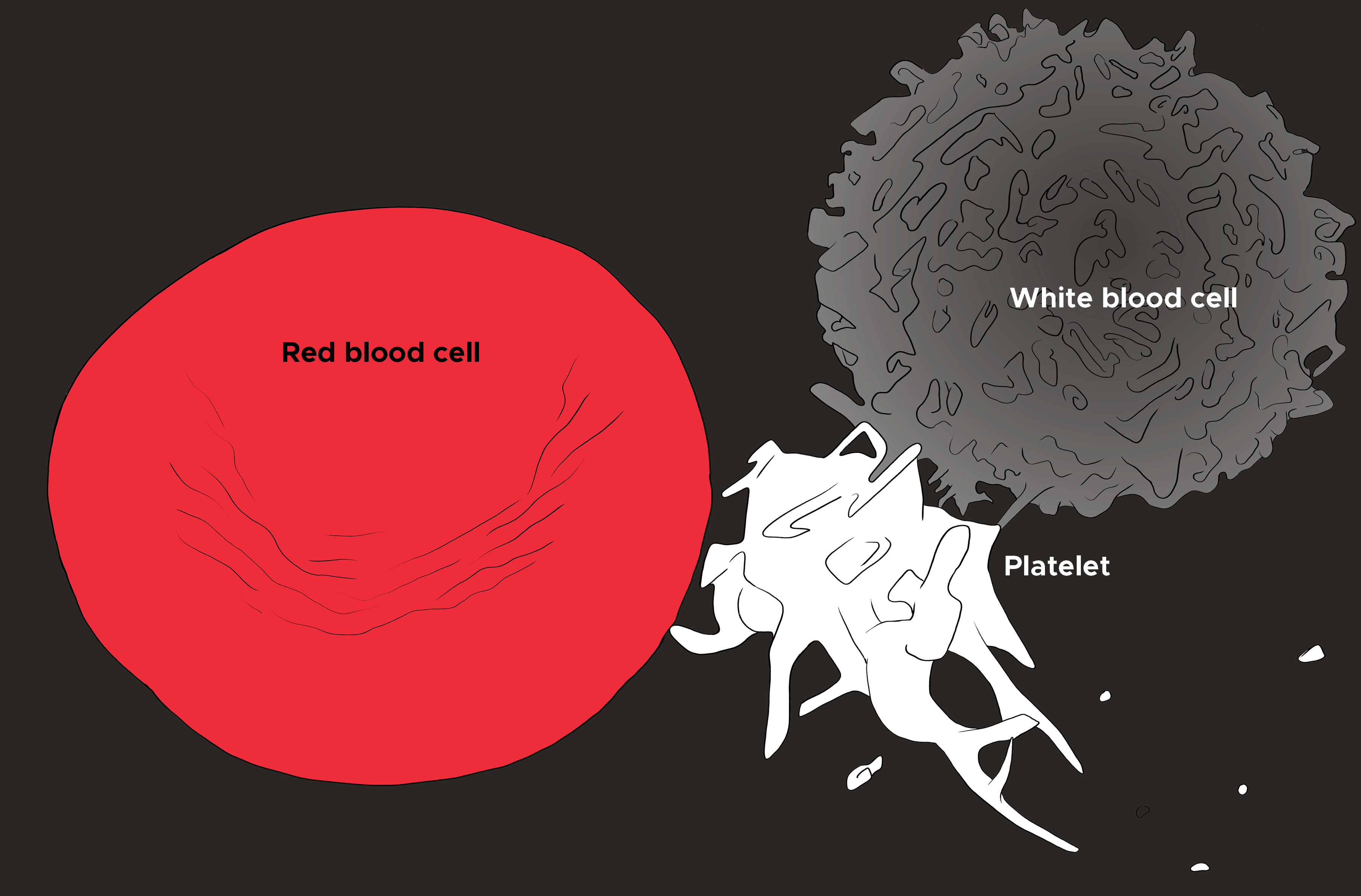

An understanding of platelet function and pathophysiology is essential in the diagnosis and management of both bleeding disorders and pathological thrombus formation in atherosclerosis (see Image. Red Blood Cell, Platelet, and White Blood Cell). Though platelet disorders can lead to excessive bleeding, as described above, it is important to note that platelet numbers generally need to be drastically reduced before spontaneous bleeding starts. Normal platelet levels in adults are between 150 to 350x10^9/L, but spontaneous bleeding often does not occur until the platelet count drops below 10x10^9/L (assuming normal platelet function). Bleeding symptoms may also be sporadic, even in severe functional platelet disorders, such as Glanzmann thrombasthenia, where the important glycoprotein IIb-IIIa is undetectable.[1] The underlying cause of the reduced platelet number or platelet dysfunction should be addressed as first-line, with platelet transfusions being a consideration if platelet counts drop below a critical threshold or in the context of life-threatening bleeding.[16]

Antiplatelet medications are commonly used in the management of atherosclerotic coronary artery and cerebrovascular disease—aspirin results in irreversible inhibition of the cyclo-oxygenase enzyme, which has a role in thromboxane formation. In patients with otherwise normal platelet function, aspirin results in a modest increase in bleeding risk, but its use is widespread because of its effectiveness in both the treatment and prevention of myocardial infarction and stroke.[1] Other medications, such as ticagrelor and clopidogrel, block the PY212 ADP receptor.[15] Glycoprotein IIb-IIIa receptor blockers such as eptifibatide and tirofiban are also extremely effective antithrombotic agents but carry a risk of significant thrombocytopaenia.[1]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

George JN. Platelets. Lancet (London, England). 2000 Apr 29:355(9214):1531-9 [PubMed PMID: 10801186]

Montague SJ, Lim YJ, Lee WM, Gardiner EE. Imaging Platelet Processes and Function-Current and Emerging Approaches for Imaging in vitro and in vivo. Frontiers in immunology. 2020:11():78. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00078. Epub 2020 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 32082328]

Hechler B, Dupuis A, Mangin PH, Gachet C. Platelet preparation for function testing in the laboratory and clinic: Historical and practical aspects. Research and practice in thrombosis and haemostasis. 2019 Oct:3(4):615-625. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12240. Epub 2019 Jul 16 [PubMed PMID: 31624781]

Blair P, Flaumenhaft R. Platelet alpha-granules: basic biology and clinical correlates. Blood reviews. 2009 Jul:23(4):177-89. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2009.04.001. Epub 2009 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 19450911]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRendu F, Brohard-Bohn B. The platelet release reaction: granules' constituents, secretion and functions. Platelets. 2001 Aug:12(5):261-73 [PubMed PMID: 11487378]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHolinstat M. Normal platelet function. Cancer metastasis reviews. 2017 Jun:36(2):195-198. doi: 10.1007/s10555-017-9677-x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28667366]

Yun SH, Sim EH, Goh RY, Park JI, Han JY. Platelet Activation: The Mechanisms and Potential Biomarkers. BioMed research international. 2016:2016():9060143. doi: 10.1155/2016/9060143. Epub 2016 Jun 15 [PubMed PMID: 27403440]

Thomas MR, Storey RF. The role of platelets in inflammation. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2015 Aug 31:114(3):449-58. doi: 10.1160/TH14-12-1067. Epub 2015 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 26293514]

Adewoyin AS, Nwogoh B. Peripheral blood film - a review. Annals of Ibadan postgraduate medicine. 2014 Dec:12(2):71-9 [PubMed PMID: 25960697]

Horobin RW, Walter KJ. Understanding Romanowsky staining. I: The Romanowsky-Giemsa effect in blood smears. Histochemistry. 1987:86(3):331-6 [PubMed PMID: 2437082]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGreinacher A, Pecci A, Kunishima S, Althaus K, Nurden P, Balduini CL, Bakchoul T. Diagnosis of inherited platelet disorders on a blood smear: a tool to facilitate worldwide diagnosis of platelet disorders. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH. 2017 Jul:15(7):1511-1521. doi: 10.1111/jth.13729. Epub 2017 Jun 4 [PubMed PMID: 28457011]

Bentfeld-Barker ME, Bainton DF. Identification of primary lysosomes in human megakaryocytes and platelets. Blood. 1982 Mar:59(3):472-81 [PubMed PMID: 6277410]

Clauser S, Cramer-Bordé E. Role of platelet electron microscopy in the diagnosis of platelet disorders. Seminars in thrombosis and hemostasis. 2009 Mar:35(2):213-23. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1220329. Epub 2009 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 19408194]

Bleeker JS, Hogan WJ. Thrombocytosis: diagnostic evaluation, thrombotic risk stratification, and risk-based management strategies. Thrombosis. 2011:2011():536062. doi: 10.1155/2011/536062. Epub 2011 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 22084665]

Ibrahim H, Kleiman NS. Platelet pathophysiology, pharmacology, and function in coronary artery disease. Coronary artery disease. 2017 Nov:28(7):614-623. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0000000000000519. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28644213]

Blumberg N, Heal JM, Phillips GL. Platelet transfusions: trigger, dose, benefits, and risks. F1000 medicine reports. 2010 Jan 27:2():5. doi: 10.3410/M2-5. Epub 2010 Jan 27 [PubMed PMID: 20502614]