Introduction

Tubal sterilization is the intentional occlusion or partial or complete removal of the fallopian tubes to provide permanent contraception in females. Sterilization is highly effective at preventing pregnancy and is the most commonly used form of contraception worldwide.[1][2] The procedure is indicated when it is desired by the patient for permanent contraception.[3] It can be performed at any time during the menstrual cycle, during cesarean delivery, and in the immediate postpartum and postabortal periods.[4] A large percentage of sterilization procedures worldwide are performed in the immediate postpartum period, including nearly half of all sterilization procedures performed in the US.[5] Procedures performed outside of the immediate postpartum or postabortal period are known as interval procedures. Presently, tubal sterilization is performed laparoscopically or through a mini-laparotomy. Previously, hysteroscopic devices have also been used; however, these devices are no longer available.[6][7]

Traditionally, interval sterilization was most often accomplished by laparoscopically occluding the tubes with clips, bands, or electrocautery, while postpartum sterilization was typically accomplished via partial salpingectomy through a mini-laparotomy.[6] More recently, however, complete bilateral salpingectomy has become the sterilization procedure of choice during interval and postpartum procedures because it decreases the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer and post-sterilization contraceptive failure compared with traditional sterilization techniques without increasing surgical risk.[8][6][9][10] A 2023 study comparing opportunistic salpingectomy to standard bilateral tubal ligation following vaginal delivery showed that for every 10,000 patients, "salpingectomy would result in 25 fewer ovarian cancer cases, 19 fewer ovarian cancer deaths, and 116 fewer unintended pregnancies than tubal ligation."[11]

During the consent process, clinicians should stress to patients that this procedure is intended to be permanent and that reversal is not always possible.[9] Young age at the time of sterilization is the strongest predictor of regret, with the probability of regret estimated to be between 12 and 20% in individuals sterilized before age 30.[4][12] To minimize this risk, the entire spectrum of alternative contraceptive options should be reviewed with the patient, with an emphasis on long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), including the intrauterine device (IUD) and contraceptive implant, both of which have efficacy rates similar to traditional tubal sterilization techniques.[13] For patients in a monogamous relationship with a single male partner, vasectomy is another essential alternative to consider because the procedure is associated with lower risks than tubal sterilization.

Although rare, post-sterilization pregnancy can occur. The cumulative 10-year failure rate of tubal sterilization using traditional occlusive methods or postpartum partial salpingectomy ranges from 7.5 to 54.3 pregnancies per 1,000 sterilization procedures, depending on the technique used and the age of the patient at sterilization, with younger ages being associated with higher rates of contraceptive failure.[14] Of note, data on the long-term failure rates of complete bilateral salpingectomy are not yet available, but rates should theoretically approach zero. If post-sterilization pregnancy occurs, there is a relatively high risk of a resulting ectopic pregnancy.[15] As with any surgical procedure, other procedural risks include bleeding, infection, injury to nearby organs, and wound and anesthesia complications.[16] Therefore, due to the importance of permanent sterilization on women's health, healthcare professionals should recognize the indications and contraindications for tubal sterilization; the risks, benefits, and complications of the procedure; the techniques available to perform this mode of sterilization; and the role of the interprofessional team in caring for patients who undergo the type of surgery.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Fallopian Tube Structure

Typical female anatomy includes 2 fallopian tubes (ie, uterine tubes or oviducts), with a tube on each side of the uterus. The tubes are paired structures emerging from the superolateral aspects of the uterus and extending laterally toward the ovaries. The tubes are a conduit between the ovary and the endometrial cavity and are approximately 10 to 12 cm long. Anatomically, the tubes are divided into 4 segments:

- Infundibulum: The tube's distal-most portion has a flared, triangular shape and feathery projections called fimbriae that extend toward the ovary and capture the released oocyte.

- Ampulla: Adjacent to the infundibulum with thinner walls and mucosal folds called plicae, this segment is where fertilization most often occurs.

- Isthmus: The narrowest portion of the tube, located between the ampulla and the uterus; this tube segment is typically occluded or excised during traditional tubal ligation techniques.

- Interstitial segment: The intramural portion of the tube that enters the uterine cornua and lies within the uterine muscle, connecting the endometrial cavity with the extrauterine segments of the fallopian tube. The tubal orifice, visible within the endometrial cavity on hysteroscopy, is known as the ostia.[17]

The walls of the fallopian tube comprise 3 layers called the endosalpinx, the myosalpinx, and the serosa. The endosalpinx is the internal mucosal layer containing cilia and secretory cells. The myosalpinx is the middle layer and is composed of smooth muscle. The movement of the cilia in the endosalpinx and peristaltic activity in the myosalpinx help move an oocyte toward the endometrial cavity. The serosa is the outermost layer of the tube.[18]

Vascular Supply and Ligament Attachments

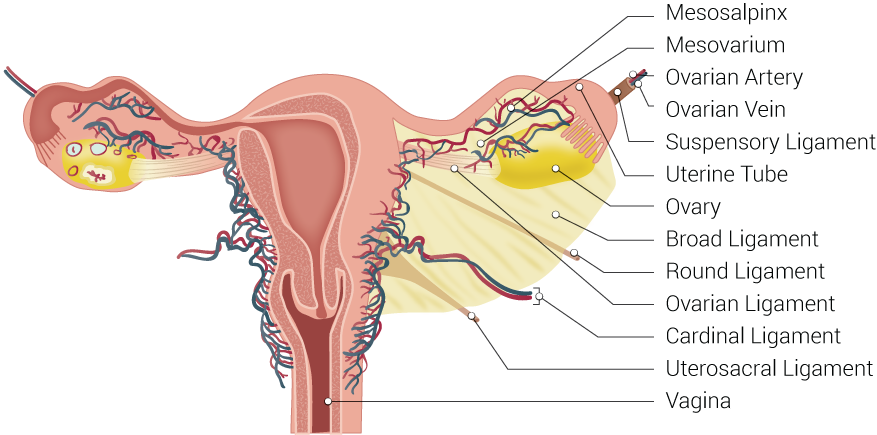

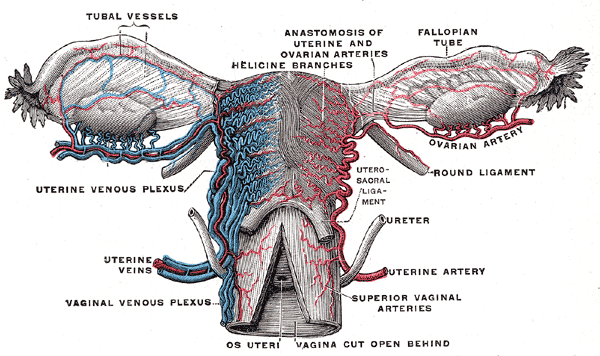

The peritoneum drapes over the uterus and tubes, forming the broad ligament. The tube is encased within a portion of the broad ligament called the mesosalpinx. The fallopian tubes are supplied by both the ovarian artery, which comes directly off the aorta and travels within the infundibulopelvic ligament (ie, the suspensory ligament of the ovary), and the ascending branch of the uterine artery (see Image. Uterine Tubal Anatomy and Ligaments). The ovarian vessels and ascending uterine vessels anastomose with one another within the mesosalpinx, immediately adjacent to the fallopian tubes (see Image. Female Reproductive System Blood Supply).[19]

Physiology

The primary function of the Fallopian tube is to transport sperm toward the egg/ovum and then allow the fertilized egg to travel back to the uterus for implantation. Thus, occlusion or removal of the Fallopian tube acts to prevent fertilization and subsequent pregnancy.

Indications

Tubal sterilization is an elective procedure. According to numerous professional organizations, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG), and the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), the only indication for tubal sterilization is an informed patient's desire for the procedure to provide permanent contraception, eliminating future fertility. An "informed patient" is an individual who fully understands the availability, effectiveness, risks, and benefits of all alternative contraceptive options and that sterilization is intended to be permanent.[4]

Certain maternal medical conditions (eg, pulmonary hypertension, cardiomyopathy) that result in very high-risk pregnancies should not be considered an indication for sterilization alone. Sterilization can be discussed as an effective contraceptive option for these patients; however, the patient's decision to be sterilized must always be made alone, free from coercion.[20]

Contraindications

The patient's lack of informed consent is the only absolute contraindication to tubal sterilization. Patients who express uncertainty regarding sterilization or their desire for future fertility should receive thorough counseling on alternative contraceptive options, and the procedure should be postponed until the patient expresses a clear, unambiguous desire for sterilization. Coerced or forced sterilization procedures are unethical and should not be performed.[20] To the best of their ability, the clinician must verify that a patient is making a well-informed choice, free from coercion.

For this reason, sterilization of incarcerated individuals should only rarely be performed because the prison environment alone can impede these individuals' ability to provide genuine informed consent without coercion. For example, between 2006 and 2010, over 140 women in California prisons signed consent forms and underwent sterilization procedures. Analysis by researchers after the fact, however, showed that many of the women felt significant pressure from both prison and hospital physicians and that many of the procedures were undesired.[20] LARCs should always be available for incarcerated people. ACOG recommends that sterilization of incarcerated women only be performed rarely and in cases where patients have declined LARCs and have expressed a strong desire for permanent contraception, ideally documented before incarceration.[20]

While there are no medical contraindications to tubal sterilization, certain patient factors may make the procedure less desirable than alternative contraceptive options (eg, LARC methods or male vasectomy) that do not require the patient to undergo an intraabdominal surgical procedure.[4] Patient factors that increase surgical risk include severe obesity, significant medical comorbidities (eg, cardiopulmonary or renal disease), or a history that increases the patient's risk for substantial intraabdominal adhesions (eg, endometriosis, intraabdominal or pelvic infections, multiple prior abdominal or pelvic surgeries).

Furthermore, young age and low parity should not be considered absolute contraindications to sterilization, though caution and thorough counseling are warranted. Specifically, the risk of regret must be thoroughly discussed with patients. Data shows that the risk of regret is between 12% and 20% for women ≤30 years of age at the time of sterilization and potentially as high as 40% in women ≤24, but this drops to about 6% for individuals >30 years of age.[21][22] While the risk of regret is higher in young patients, clinicians must avoid paternalism and honor an individual's autonomous, informed choice.[20] Accordingly, ACOG recommends that clinicians err on the side of greater patient autonomy, arguing that "eliminating the risk of regret by limiting patient autonomy generally is considered by bioethicists to be worse than allowing a patient to make a possibly erroneous choice."[20] ACOG also notes, however, that all individuals must be well-informed regarding the permanence of tubal sterilization and that alternative, reversible options are available and as effective.

Equipment

There are multiple ways to perform tubal sterilization; the choice is typically driven by surgeon familiarity and preference. Patient preference and other patient factors (eg, significant pelvic adhesions limiting tubal mobility) may also influence the choice of procedure and technique.

Postpartum complete or partial salpingectomies are performed using traditional surgical instruments and sutures or, increasingly, hand-held electrosurgical devices. Interval bilateral complete salpingectomy is usually accomplished laparoscopically using standard laparoscopic equipment and electrosurgical devices with coagulation and cutting abilities. However, interval salpingectomies may also be performed with traditional surgical instruments through a minilaparotomy, which occurs most often in settings with limited laparoscopic resources.

Tubal occlusion, performed laparoscopically or via minilaparotomy, may be accomplished with any of the following:

- Titanium clips

- Spring-loaded clips

- Silicone bands

- Electrosurgical forceps for tubal desiccation [4]

Between 2002 and 2018, 2 hysteroscopic devices were also available for sterilization procedures in the US. One was removed from the marketplace in 2012 after a successful lawsuit for patent infringement, and the other was voluntarily removed in 2018 due to declining sales after a series of successful high-profile legal cases concerning long-term complications. Currently, there are no hysteroscopic devices available for sterilization procedures.[4]

Personnel

An interprofessional surgical team is required to complete the procedure safely, including:

- Primary surgeon

- Anesthesiologist or certified nurse anesthetist

- Surgical technician

- Circulating nurse

- Preoperative nurse

- Postanesthesia care unit (PACU) nurse

Preparation

Procedure Timing

Sterilization procedures can be performed:

- Postpartum: At the time of cesarean delivery or in the immediate postpartum period (ie, before discharge) after a vaginal delivery

- Postabortal: Immediately following an early pregnancy loss or induced abortion

- Interval: At a time unrelated to recent pregnancy, at any time during the menstrual cycle

Clinicians should be aware of local regulations regarding required time intervals between obtaining informed consent and completing the procedure and relay this information to the patient. Legal restrictions may also apply to some individuals. For example, in the US, individuals with federally funded health insurance must have their consent form signed between 30 and 180 days before their procedure and must be at least 21 years of age, though some states have altered these requirements.[23]

Obtaining Informed Consent

Clinicians must obtain and document informed consent before performing a tubal sterilization procedure. This includes discussing the procedure's nature, purpose, and expected outcomes with the patient. The potential risks and alternative options should also be discussed, including the consequences of not performing the procedure.[16] Furthermore, ACOG and other authorities recommend explicitly reviewing the procedure's permanent nature, the availability and effectiveness of LARCs and vasectomy, the possibility of post-sterilization contraceptive failure, the risk of anesthesia, and the need for barrier protection against sexually transmitted infections.[4][20][24]

While discussing the permanence of sterilization procedures, clinicians should clarify that while sterilization reversal procedures may be available, they may not be effective, are associated with an increased risk of ectopic pregnancy, and are typically very expensive. Additionally, reversal is not possible when a bilateral salpingectomy is performed.

- Nature of the procedure: The planned tubal sterilization technique should be discussed with the patient. However, discussing alternative approaches with the patient is also prudent if intraoperative factors (eg, adhesive disease) make one method more complex or riskier. Additionally, the same technique does not have to be applied to both tubes for the procedure to be effective. For instance, if a bilateral salpingectomy is planned, but significant tubal adhesions are encountered unexpectedly on the right side, the right side may be occluded with a clip while the left tube is completely excised. The potential for scenarios like this should be discussed with the patient beforehand.

- Benefits: Sterilization is a safe, highly effective, hormone-free, permanent form of contraception that is effective immediately and requires no ongoing effort on behalf of the patient. Additionally, the procedure appears to decrease the risk of ovarian cancer. While traditional sterilization methods (eg, clips, bands, and partial salpingectomy) confer some protection, especially against endometrioid and clear cell ovarian carcinomas, bilateral salpingectomy significantly reduces the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer. Epithelial ovarian cancer is responsible for 90% of all ovarian cancers and 90% of all ovarian cancer deaths.[25][26] A traditional tubal ligation is estimated to reduce ovarian cancer risk by 13% to 41%, while a bilateral salpingectomy reduces the risk by 42% to 78%.[27] Therefore, the American Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) and ACOG recommend that a bilateral salpingectomy be considered in women who desire permanent sterilization to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer.[25] Bilateral salpingectomy also eliminates the chance of a subsequent ectopic tubal pregnancy and appears to have lower failure rates than traditional sterilization methods.[8] Neither traditional sterilization techniques nor bilateral salpingectomy appears to affect ovarian reserve.[28]

- Risks and other expected outcomes: The risks of regretting a sterilization procedure or sterilization failure must be discussed with patients. Additionally, it should be emphasized that younger age at the time of sterilization increases both of these risks.[4][14] Patients also should be aware that the current use of hormonal contraception may be suppressing heavier menstrual flow and dysmenorrhea that can be unmasked when hormonal contraception is discontinued after a sterilization procedure. Sterilization itself, however, has not been shown to alter menstrual patterns.[4] Additionally, sterilization does not protect against sexually transmitted infections. Other general surgical risks of the procedure include injury to the surrounding organs, bleeding potentially requiring a blood transfusion, infection, wound complications, anesthesia complications, and venous thromboembolic events.

Preoperative Evaluation

Before heading to the operating suite, patients should undergo a general medical assessment, including a heart, lung, and abdominal exam. Primary care clinicians should assess patients with medical comorbidities to optimize their perioperative care. A pelvic exam is typically performed preoperatively to evaluate the mobility of the pelvic organs and screen for abnormalities that may affect the care plan. Although not required, a pelvic ultrasound may also be obtained to screen the internal gynecologic organs for abnormalities that could be encountered and addressed during a laparoscopic procedure. A pelvic exam or ultrasound allows the clinician and patient to discuss any findings (eg, an ovarian cyst) and create a comprehensive, informed care plan before surgery. Similarly, clinicians should ensure a patient's cervical cancer screening is current before the procedure. When indicated, a diagnostic cervical excision procedure can be performed in addition to the sterilization procedure. If cancer is identified, alternative plans may be recommended. Clinicians should also counsel patients on the risk of luteal phase pregnancy and ensure they have appropriate contraception leading up to their procedure, as the patient desires. A pregnancy test should be performed on the day of surgery, and if positive, the procedure is typically postponed until the postpartum period or postabortal period.

Perioperative Prophylaxis Against Infection

Preoperative antibiotics are not indicated before standard interval sterilization procedures performed either laparoscopically or via a minilaparotomy.[29] Patients undergoing cesarean delivery should receive standard antibiotic prophylaxis, typically with cefazolin with or without azithromycin. Patients should be advised to shower or bath with soap or an antiseptic agent the night before surgery. The abdominal skin should be prepped with an antiseptic agent such as chlorhexidine, and the vagina should be prepped with povidone-iodine or 4% chlorhexidine gluconate if a uterine manipulator is to be used.[29]

Technique or Treatment

Laparoscopic Approaches

Laparoscopy is the primary method for interval tubal sterilization procedures.[30] The same technique does not have to be used for both tubes. However, each fallopian tube must be either fully or partially removed or completely occluded.

Bilateral salpingectomy

Laparoscopic bilateral salpingectomy is becoming the preferred method of tubal sterilization because the procedure is associated with lower rates of ovarian cancer without increasing surgical risk. Though long-term data is not yet available, bilateral salpingectomy is theoretically the most effective sterilization procedure. Additionally, salpingectomy is often preferred if the tube appears grossly abnormal (eg, hydrosalpinx).[3]

The patient is placed in a dorsal lithotomy position under general anesthesia and surgically prepared and draped using standard aseptic techniques. The patient's bladder should then be emptied with a urinary catheter. The surgeon usually will conduct a pelvic exam and place a uterine manipulator, carefully changing gloves before beginning the abdominal portion of the procedure to prevent cross-contamination.[31] Standard laparoscopic techniques are used to enter and insufflate the abdomen, which commonly only requires 1 or 2 port sites.[32] The abdomen and pelvic cavities should be inspected, and the fallopian tubes should be followed out to their fimbriated ends to confirm the proper structure has been identified, as the proximal fallopian tube may be easily confused with the round ligament. If adhesions or abnormal anatomy are present, the ureters should be identified to avoid inadvertent ureteral injury. Using standard surgical techniques, pelvic adhesions limiting tubal mobility can be carefully taken down.

The tube is excised using laparoscopic instruments, typically electrosurgical devices with coagulation and cutting abilities. To completely excise the tube, all of the attachment points must be transected, including the proximal isthmus immediately adjacent to the uterine cornua, the mesosalpinx immediately underneath the entire length of the tube out to the fimbriated end, and the tuboovarian ligament. The procedure can be accomplished by working from the medial side to the lateral side or vice versa. Following removal from the abdominal cavity, the tubal specimens should be sent for pathologic evaluation. Finally, hemostasis should be assured before removing all surgical instruments and closing the laparoscopic port sites.[33][3]

Tubal occlusion procedures

Laparoscopic tubal occlusions are performed in a very similar fashion to a laparoscopic salpingectomy. Instead of excising the tube, attention is focused on the mid-isthmic tubal segment for an occlusive procedure. This area is the thinnest and, therefore, the easiest and most effective portion to occlude. In contrast, occlusion at the proximal isthmus, within 2 cm of the uterine cornua, carries the theoretical risk of fistula formation; occlusion at more distal tubal segments is associated with higher contraceptive failure rates.[34]

If electrosurgical desiccation is chosen, Kleppinger bipolar grasping forceps are frequently used to apply radiofrequency energy to the tube, resulting in desiccation and occlusion of the tubal lumen. Monopolar electrocoagulation is rarely used because it increases the risk of thermal bowel injury.[4] The mid-isthmic portion of the tube should be grasped with the forceps, ensuring the entire width of the tube is secured between the prongs and energy is applied. This should be done at ≥3 contiguous sites along the tube, resulting in ≥3 cm of fulgurated tube. This technique results in the lowest failure rate compared to other methods. Data from the US Collaborative Review of Sterilization (CREST) study shows that fulguration of at least 3 sites was associated with only 3.2 failures per 1,000 procedures compared to 12.9 failures if fewer than 3 were fulgurated.[35] A current flow meter, or ammeter, can be used to confirm the complete desiccation of the tube.

Clinicians using an occlusive device, including clips or a silicone band, should follow the manufacturer's instructions, using device-specific applicators to apply the device to the mid-isthmic portion of the tube. Clips should be placed across the entire width of the tube. Bands are placed by drawing the tubal segment into the applicator, so sufficient tubal mobility is required for correct placement.[4] Excessive traction on the tube during device placement may result in tubal laceration and hemorrhage. Misapplication and contraceptive failure are more likely if the tubes are thickened, dilated, or otherwise abnormal. A prudent surgeon should verify the correct placement of the clip or band following its deployment. If the mechanical device does not appear to have been placed correctly, a second clip may be placed, or an alternative technique should be used to ensure sterilization.[3]

Open Approaches

Tubal sterilization can also be accomplished via an open approach. If the patient undergoes a cesarean delivery, tubal sterilization is performed immediately following hysterotomy closure and before closing the abdominal incision. Following a vaginal delivery, tubal sterilization is typically accomplished through a mini-laparotomy under regional anesthesia. Additionally, a mini-laparotomy may be used in patients with significant risks for laparoscopy and in settings with limited laparoscopic resources.[24]

Mini-laparotomies are abdominal incisions approximately 2 to 3 cm in length. For tubal sterilization, the incision should be located near the uterine fundus, so the mini-laparotomy is typically placed in the infraumbilical fold for postpartum procedures and in the suprapubic region for interval procedures.[4] Similar to the technique described above, the tubes are transected near the uterine cornua, and the mesosalpinx is transected along the length of the tube, allowing the full tube to be excised. If available, handheld bipolar electrosurgical devices are frequently chosen over instruments used in traditional suture-ligation techniques because the devices have been shown to decrease the operative time while improving surgeon-reported outcomes.[36]

Before SGO recommended opportunistic bilateral salpingectomy for ovarian cancer risk reduction, sterilizations performed through a mini-laparotomy were typically accomplished with either a partial salpingectomy or occlusive clips. Generally, a Parkland or Pomeroy technique is used to perform a partial or complete salpingectomy, and at least 2 cm of the tube should be excised in both methods.[3][32]

Parkland technique

The mid-isthmic portion of the fallopian tube is elevated with a Babcock clamp, and a window is created in the avascular plane of the mesosalpinx beneath the tube. Two pieces of dissolvable suture (eg, 0-chromic or plain gut) are passed through this window and used to ligate the proximal and distal ends of a 2- to 3-cm segment of the isthmic fallopian tube. The ligated tube segment is then sharply excised between the sutures. The tubal lumen should be visualized within the cut ends of the tube to confirm the resection of the correct anatomic structure.[3][32] (see Image. Parkland Tubal Ligation).

Pomeroy method

The mid-isthmic portion of the tube is elevated, allowing the proximal and distal sides of the tube to come together. A single strand of a rapidly absorbable suture (eg, 1-0 or 0 plain gut suture) is placed around both the proximal and distal portions of the tube, creating a loop or "knuckle" of the fallopian tube above the suture. A second suture may be placed under the first suture if desired. The tube segment above the suture ligation is then sharply excised. The tubal lumen should be visualized within the cut ends of the tube to confirm the resection of the correct anatomic structure. As the suture is absorbed, the proximal and distal ends will fall away from each other.[3][32]

Hysteroscopic Approaches

Previously, devices to perform hysteroscopic tubal sterilization were available; no such devices are currently available in the US. The most popular hysteroscopic sterilization device allowed the clinician to thread a small metallic coil into each fallopian tube. These coils then induced a local inflammatory response, forming scar tissue that occluded the tubes over the next several months. This procedure, therefore, was not immediately effective and required a confirmatory hysterosalpingogram 3 months following the procedure to ensure tubal occlusion. Concern exists that these coils may increase the risk of chronic pelvic pain potentially due to perforation, coil migration, or nickel allergy. However, the data has been mixed, and the true relationship between coil placement and chronic pelvic pain is unclear.[37][3] Therefore, women who have already undergone this procedure and have not developed adverse effects may keep the device in place.[3]

Complications

Complications Unique to Sterilization

The most significant complications unique to tubal sterilization include contraceptive failure and the risk of sterilization regret. The most comprehensive data regarding sterilization outcomes is from the CREST study, which prospectively followed 10,685 patients for 14 years who underwent sterilization procedures in the US between 1978 and 1987.[14] Experts have widely acknowledged that this data set is outdated, as medical practice and societal norms have changed significantly since that time; however, the study remains the most comprehensive.

Contraceptive Failure

According to the CREST study, the cumulative 10-year failure rate is 18.5 per 1,000 procedures when all procedures are aggregated; notably, this does not include data on complete salpingectomy or titanium clips. The cumulative risk of failure was lowest for those undergoing either postpartum partial salpingectomy or bipolar coagulation, with each having a risk of 7.5 failures per 1,000 procedures. Failure rates were highest for those sterilized with spring-loaded clips, with 36.5 failures per 1,000 procedures.[14] The failure rate was also higher in those sterilized at a young age, possibly due to higher natural fertility rates and more fertile years in younger women than those sterilized at older ages. A 2016 Cochrane review of 19 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving over 13,000 women found that failure rates at 1 year were <5 per 1,000 procedures among all methods studied, which included titanium clips but not complete salpingectomy. The review found no deaths and noted that significant morbidity was rare.[38]

Ectopic Pregnancy

If a procedure other than complete salpingectomy was performed, the 10-year probability of an ectopic pregnancy is 7.3 per 1,000 procedures.[15] The risk of ectopic pregnancy appears to be highest among women sterilized by bipolar coagulation before age 30, with 17.1 ectopic pregnancies per 1,000 procedures.[4][15] Patients should, therefore, be counseled to present for evaluation early if they suspect pregnancy.

Regret

The most significant factor affecting a patient's risk of regret is their age, with the risk of regret decreasing with advancing age. The average probability of regret for individuals sterilized before age 30 is estimated to be between 12% and 20%, with higher rates in younger individuals. The CREST study noted rates of regret as high as 40% in people sterilized between the ages of 18 and 24 years. Those sterilized after age 30 are estimated to have only about a 6% risk of regret.[21][22]

The risk of regret also appears to decrease as the interval increases between the youngest child's birth and the procedure's completion.[22] However, while immediate postpartum sterilization appears to increase the regret risk, immediate postabortal sterilization does not.[22][39] Additionally, the number of living children an individual has, including those without children, is not associated with increased regret.[4] Contrary to previous thinking, the CREST study found that the risk of regret in women sterilized before age 30 was lowest among nulliparous women, with a regret rate of only 6.3%.[22]

Other risk factors for regret include feeling uninformed about the procedure, being unaware of alternative contraceptive methods, and making the decision under pressure from a partner or due to medical indications. To minimize the risk of regret, patients should be thoroughly counseled on alternative reversible contraceptive options, focusing on long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods.[3] For patients who want to regain fertility following a sterilization procedure, options include in vitro fertilization (IVF) and, if significant portions of the tube remain, tubal reanastomosis.[22][32]

Postablation Tubal Sterilization Syndrome

Individuals who undergo a sterilization procedure after or concurrently with an endometrial ablation may experience cyclic or intermittent pelvic pain following the procedure due to hematometra in the uterine cornua. The incidence is estimated to be approximately 10% to 20% of individuals undergoing both procedures.[40][41]

General Surgical Complications

Additional surgical complications include:

- Internal injury to the bowel, bladder, ureters, vasculature, or nerves

- Bleeding due to vascular injury or unintentional tubal transection during clip or band placement

- Transfusion

- Infection

- Pain

- Conversion from laparoscopy to laparotomy

- Anesthesia complications

- Death (rarely) [3]

Clinical Significance

Tubal sterilization is the most commonly used form of contraception worldwide. Approximately half of all pregnancies in the US are unintended, and tubal sterilization provides a safe, highly effective, hormone-free, low-maintenance contraceptive option for individuals who want to eliminate their fertility.

The only indication is a patient's desire for the procedure. However, proper informed consent when discussing family planning choices can only be obtained when the patient understands the permanent nature of the procedure and the risks and benefits of every contraceptive option. Therefore, clinicians need to know how to effectively counsel patients regarding this procedure and how to perform it correctly.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Tubal sterilizations are performed by physicians trained in obstetrics and gynecology (OB/GYN). However, many individuals first present to their primary care clinician requesting information on the procedure or to discuss contraceptive options in general before requiring an OB/GYN referral. Furthermore, comprehensive contraceptive counseling, including obtaining informed consent, is required before the procedure can be performed. One study demonstrated wide variations in patient counseling and recommended standardizing patient education during the consent process.[42] On the day of surgery, an interdisciplinary team, including the surgeon, anesthesiologist, surgical technicians, and nursing staff, all play a critical role in ensuring optimal surgical outcomes.[43] Excellent communication between team members and careful documentation are both vital.

Unfortunately, several barriers may also prevent patients who desire it from undergoing the procedure. Operating room staff or equipment may be unavailable for postpartum patients for these unscheduled, “nonurgent” cases. Certain regions or insurance programs can have specific requirements. For instance, Medicaid in the US requires a patient to be at least 21 years of age and have a consent form signed between 30 and 180 days before the procedure. Additionally, some institutions or clinicians have religious objections to sterilization procedures and do not perform them. Healthcare personnel can work together to reduce these barriers by developing policies and procedures surrounding consent forms and scheduling postpartum procedures.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

- Ensure the patient understands sterilization procedures are intended to be permanent.

- Ensure the patient understands what type of procedure will be performed.

- Ensure a valid consent form has been signed.

- Appropriately prep and drape the patient.

- Assist the surgeon as requested.

- Ensure instrument and sponge counts are correct at the beginning and end of the procedure.

- Prepare the instrument tray for sterilization

- Label the specimen for the pathologist

- Monitor the patient before, during, and after the surgery.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Uterine Tubal Anatomy and Ligaments. Shown in this illustration are anatomical structures surrounding the uterus and fallopian or uterine tubes, including the mesosalpinx, mesovarium, ovarian artery, ovarian vein, suspensory ligament, uterine tube, ovary, broad ligament, round ligament, ovarian ligament, cardinal ligament, uterosacral ligament, and vagina.

Contributed by B Palmer

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Female Reproductive System Blood Supply. Anterior-view illustration showing the fallopian tube vessels, anastomosis of the uterine and ovarian arteries, helicine branches, ovarian artery, uterine venous plexus, uterine artery, and veins, superior vaginal arteries, and vaginal venous plexus. Other structures shown are the ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, os uteri, uterosacral ligament, and ureter.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Clark NV, Endicott SP, Jorgensen EM, Hur HC, Lockrow EG, Kern ME, Jones-Cox CE, Dunlow SG, Einarsson JI, Cohen SL. Review of Sterilization Techniques and Clinical Updates. Journal of minimally invasive gynecology. 2018 Nov-Dec:25(7):1157-1164. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2017.09.012. Epub 2017 Sep 20 [PubMed PMID: 28939482]

Gariepy AM, Lewis C, Zuckerman D, Tancredi DJ, Murphy E, McDonald-Mosley R, Sonalkar S, Hathaway M, Nunez-Eddy C, Schwarz EB. Comparative effectiveness of hysteroscopic and laparoscopic sterilization for women: a retrospective cohort study. Fertility and sterility. 2022 Jun:117(6):1322-1331. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2022.03.001. Epub 2022 Apr 12 [PubMed PMID: 35428480]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 208 Summary: Benefits and Risks of Sterilization. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2019 Mar:133(3):592-594. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003134. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30801465]

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 208: Benefits and Risks of Sterilization. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2019 Mar:133(3):e194-e207. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003111. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30640233]

. Access to Postpartum Sterilization: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 827. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2021 Jun 1:137(6):e169-e176. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004381. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33760784]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDanis RB, Della Badia CR, Richard SD. Postpartum Permanent Sterilization: Could Bilateral Salpingectomy Replace Bilateral Tubal Ligation? Journal of minimally invasive gynecology. 2016 Sep-Oct:23(6):928-32. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2016.05.006. Epub 2016 May 24 [PubMed PMID: 27234430]

Sánchez-Cuerda C, Cuadra M, Cabrera Y, Duch S, Fabra S, Peay-Pinacho J, Álvarez P, Rubio J, Álvarez Bernardi J, Lobo P. Analysis of clinical data associated with Essure® sterilization devices: An expanded case series. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 2022 Nov:278():125-130. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2022.09.018. Epub 2022 Sep 21 [PubMed PMID: 36166976]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCastellano T, Zerden M, Marsh L, Boggess K. Risks and Benefits of Salpingectomy at the Time of Sterilization. Obstetrical & gynecological survey. 2017 Nov:72(11):663-668. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0000000000000503. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29164264]

Kim AJ, Barberio A, Berens P, Chen HY, Gants S, Swilinski L, Acholonu U, Chang-Jackson SC. The Trend, Feasibility, and Safety of Salpingectomy as a form of Permanent Sterilization. Journal of minimally invasive gynecology. 2019 Nov-Dec:26(7):1363-1368. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2019.02.003. Epub 2019 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 30771489]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRunnebaum IB, Kather A, Vorwergk J, Cruz JJ, Mothes AR, Beteta CR, Boer J, Keller M, Pölcher M, Mustea A, Sehouli J. Ovarian cancer prevention by opportunistic salpingectomy is a new de facto standard in Germany. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology. 2023 Aug:149(10):6953-6966. doi: 10.1007/s00432-023-04578-5. Epub 2023 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 36847838]

Wagar MK, Forlines GL, Moellman N, Carlson A, Matthews M, Williams M. Postpartum Opportunistic Salpingectomy Compared With Bilateral Tubal Ligation After Vaginal Delivery for Ovarian Cancer Risk Reduction: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2023 Apr 1:141(4):819-827. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000005118. Epub 2023 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 36897130]

Hardy E, Bahamondes L, Osis MJ, Costa RG, Faúndes A. Risk factors for tubal sterilization regret, detectable before surgery. Contraception. 1996 Sep:54(3):159-62 [PubMed PMID: 8899257]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSridhar A, Friedman S, Grotts JF, Michael B. Effect of theory-based contraception comics on subjective contraceptive knowledge: a pilot study. Contraception. 2019 Jun:99(6):368-372. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2019.02.010. Epub 2019 Mar 13 [PubMed PMID: 30878456]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePeterson HB, Xia Z, Hughes JM, Wilcox LS, Tylor LR, Trussell J. The risk of pregnancy after tubal sterilization: findings from the U.S. Collaborative Review of Sterilization. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1996 Apr:174(4):1161-8; discussion 1168-70 [PubMed PMID: 8623843]

Peterson HB, Xia Z, Hughes JM, Wilcox LS, Tylor LR, Trussell J. The risk of ectopic pregnancy after tubal sterilization. U.S. Collaborative Review of Sterilization Working Group. The New England journal of medicine. 1997 Mar 13:336(11):762-7 [PubMed PMID: 9052654]

Hanson M, Pitt D. Informed consent for surgery: risk discussion and documentation. Canadian journal of surgery. Journal canadien de chirurgie. 2017 Feb:60(1):69-70 [PubMed PMID: 28234594]

Dagar M, Srivastava M, Ganguli I, Bhardwaj P, Sharma N, Chawla D. Interstitial and Cornual Ectopic Pregnancy: Conservative Surgical and Medical Management. Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology of India. 2018 Dec:68(6):471-476. doi: 10.1007/s13224-017-1078-0. Epub 2017 Nov 28 [PubMed PMID: 30416274]

Han J, Sadiq NM. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Fallopian Tube. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31613440]

Craig ME, Sudanagunta S, Billow M. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Broad Ligaments. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29763118]

. Committee Opinion No. 695: Sterilization of Women: Ethical Issues and Considerations. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2017 Apr:129(4):e109-e116. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002023. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28333823]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDanvers AA, Evans TA. Risk of Sterilization Regret and Age: An Analysis of the National Survey of Family Growth, 2015-2019. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2022 Mar 1:139(3):433-439. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004692. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35115436]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHillis SD, Marchbanks PA, Tylor LR, Peterson HB. Poststerilization regret: findings from the United States Collaborative Review of Sterilization. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1999 Jun:93(6):889-95 [PubMed PMID: 10362150]

Arora KS, Chua A, Miller E, Boozer M, Serna T, Bullington BW, White K, Gunzler DD, Bailit JL, Berg K. Medicaid and Fulfillment of Postpartum Permanent Contraception Requests. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2023 May 1:141(5):918-925. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000005130. Epub 2023 Apr 5 [PubMed PMID: 37103533]

Stuart GS, Ramesh SS. Interval Female Sterilization. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2018 Jan:131(1):117-124. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002376. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29215509]

. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 774: Opportunistic Salpingectomy as a Strategy for Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Prevention. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2019 Apr:133(4):e279-e284. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003164. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30913199]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMatz M, Coleman MP, Sant M, Chirlaque MD, Visser O, Gore M, Allemani C, & the CONCORD Working Group. The histology of ovarian cancer: worldwide distribution and implications for international survival comparisons (CONCORD-2). Gynecologic oncology. 2017 Feb:144(2):405-413. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.10.019. Epub 2016 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 27931752]

Ely LK, Truong M. The Role of Opportunistic Bilateral Salpingectomy vs Tubal Occlusion or Ligation for Ovarian Cancer Prophylaxis. Journal of minimally invasive gynecology. 2017 Mar-Apr:24(3):371-378. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2017.01.001. Epub 2017 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 28087480]

Ganer Herman H, Gluck O, Keidar R, Kerner R, Kovo M, Levran D, Bar J, Sagiv R. Ovarian reserve following cesarean section with salpingectomy vs tubal ligation: a randomized trial. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2017 Oct:217(4):472.e1-472.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.04.028. Epub 2017 Apr 25 [PubMed PMID: 28455082]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 195: Prevention of Infection After Gynecologic Procedures. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2018 Jun:131(6):e172-e189. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002670. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29794678]

Golditch IM. Laparoscopy: advances and advantages. Fertility and sterility. 1971 May:22(5):306-10 [PubMed PMID: 4252494]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBlumenthal PD. Laparoscopic sterilization in the supine position using the Ramathibodi uterine manipulator. Fertility and sterility. 1995 Jul:64(1):204-7 [PubMed PMID: 7789563]

Micks EA, Jensen JT. Permanent contraception for women. Women's health (London, England). 2015 Nov:11(6):769-77. doi: 10.2217/whe.15.69. Epub 2015 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 26626698]

Dubuisson JB, Aubriot FX, Cardone V. Laparoscopic salpingectomy for tubal pregnancy. Fertility and sterility. 1987 Feb:47(2):225-8 [PubMed PMID: 2949999]

Oskowitz S, Haverkamp AD, Freedman WL. Experience in a series of fimbriectomies. Fertility and sterility. 1980 Oct:34(4):320-3 [PubMed PMID: 6998747]

Peterson HB, Xia Z, Wilcox LS, Tylor LR, Trussell J. Pregnancy after tubal sterilization with bipolar electrocoagulation. U.S. Collaborative Review of Sterilization Working Group. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1999 Aug:94(2):163-7 [PubMed PMID: 10432120]

Ostby SA, Blanchard CT, Sanjanwala AR, Szychowski JM, Leath CA 3rd, Huh WK, Subramaniam A. Feasibility, Safety, and Provider Perspectives of Bipolar Electrosurgical Cautery Device for (Opportunistic or Complete) Salpingectomy at the Time of Cesarean Delivery. American journal of perinatology. 2022 Jun 21:():. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-1748525. Epub 2022 Jun 21 [PubMed PMID: 35728603]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYunker AC, Ritch JM, Robinson EF, Golish CT. Incidence and risk factors for chronic pelvic pain after hysteroscopic sterilization. Journal of minimally invasive gynecology. 2015 Mar-Apr:22(3):390-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2014.06.007. Epub 2014 Jun 19 [PubMed PMID: 24952343]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLawrie TA, Kulier R, Nardin JM. Techniques for the interruption of tubal patency for female sterilisation. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2016 Aug 5:2016(8):CD003034. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003034.pub4. Epub 2016 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 27494193]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceChi IC, Jones DB. Incidence, risk factors, and prevention of poststerilization regret in women: an updated international review from an epidemiological perspective. Obstetrical & gynecological survey. 1994 Oct:49(10):722-32 [PubMed PMID: 7816397]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSharp HT. Endometrial ablation: postoperative complications. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2012 Oct:207(4):242-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.04.011. Epub 2012 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 22541856]

Chaves KF, Merriman AL, Hassoun J, Cedó Cintrón LE, Zhao Z, Yunker AC. Post-ablation tubal sterilization syndrome: Does route of sterilization matter? Contraception. 2022 Mar:107():17-22. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.10.015. Epub 2021 Nov 6 [PubMed PMID: 34752776]

Bharathan R, Rawesh R, Ahmed H. Written consent for laparoscopic tubal occlusion and medico-legal implications. The journal of family planning and reproductive health care. 2009 Jul:35(3):177-9. doi: 10.1783/147118909788707823. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19622209]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMao J, Guiahi M, Chudnoff S, Schlegel P, Pfeifer S, Sedrakyan A. Seven-Year Outcomes After Hysteroscopic and Laparoscopic Sterilizations. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2019 Feb:133(2):323-331. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003092. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30633141]