Introduction

Epithelioid sarcoma is a rare and aggressive soft tissue sarcoma characterized by both epithelial and mesenchymal differentiation. This condition most commonly affects young adults and typically presents as a painless and slow-growing mass often located in the distal extremities.[1] Epithelioid sarcoma is locally invasive and frequently metastasizes to regional lymph nodes and distant sites. Diagnosis is determined by tissue biopsy, while imaging studies are essential for assessing the extent of the primary tumor and identifying metastatic disease.

Complete surgical resection is curative in early-stage disease. However, local recurrence and late distant metastases may occur, necessitating long-term surveillance.[2] Radiation therapy may be used as an adjunct treatment and as a palliative measure. Recently, treatment options have evolved with the development of targeted therapies, which aim to improve patient outcomes.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Epithelioid sarcomas are malignant tumors with both mesenchymal and epithelial cell differentiation. Up to 90% of epithelioid sarcomas show loss of integrase interactor-1 (INI-1) expression.[3] INI-1 is part of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex, which is expressed in all normal nucleated cells. This chromatin remodeling complex is essential for biological function as it alters nucleosomes to allow for DNA transcription.

INI-1, or SMARCB1, is located on chromosome 22 at the 22q11 band. A spectrum of gene deletions and rearrangements, including translocation events involving the 22q11 locus, are responsible for tumorigenesis in INI-1–deficient epithelioid sarcomas.[4] Intriguingly, an association with prior trauma at the site of the tumor has been noted in up to 27% of occurrences.[5] However, previous trauma to the distal extremity is logically a common occurrence, making it difficult to definitively speculate on its role as an inciting event.

Epidemiology

Epithelioid sarcomas are rare, accounting for less than 1% of soft tissue sarcomas.[2] They predominantly affect men, with a male-to-female ratio of up to 2:1.[6] Most reported tumors occur in young males aged 10 to 45.[2][5][1][7] The age range spans from 4 to 90, with a median age of 27.[6]

Histopathology

Histologically, the conventional or usual type of epithelioid sarcoma exhibits a nodular or lobular architecture with central areas of necrosis surrounded by polygonal epithelioid cells characterized by relatively abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. This appearance under low-power microscopy resembles a granulomatous lesion. Nuclear atypia is minimal, and mitotic figures are typically absent.[1][5] Tumor cells at the periphery often exhibit a spindled or sarcomatous appearance. Various histological patterns further complicate the diagnosis, as some tumors may resemble angiomatoid or fibromatoid lesions.[6][8] These features can lead the pathologist to consider differential diagnoses, including vascular neoplasms, benign processes such as fibromatosis, or even reactive lesions such as nodular fasciitis.

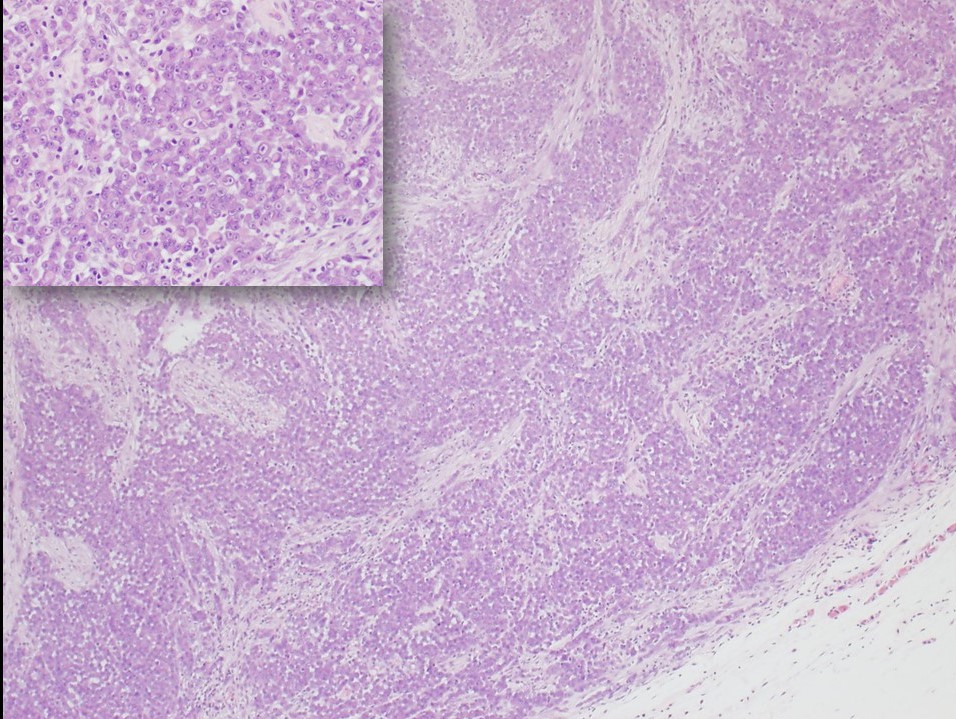

The proximal-type variant of epithelioid sarcoma lacks the granulomatous pattern of necrosis (see Image. Epithelioid Sarcoma, Proximal-Type). Instead, the tumor is characterized by cellular nodules exhibiting increased cytologic pleomorphism, nuclear atypia, and sometimes signet-ring-like vacuolation.[5][7] Rhabdoid morphology with prominent nucleoli is characteristic of this lesion. Although the proximal type is typically found near the trunk, proximal variants of epithelioid sarcoma are defined by histological features, not location.[2][9] Furthermore, the usual proximal location of this variant increases diagnostic challenges due to overlapping features with metastatic carcinoma, which often occur in proximal sites such as the groin and pelvic area.[7]

The immunohistochemical profile of epithelioid sarcoma typically shows strong expression of cytokeratins, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), and vimentin, and often CD34 positivity, which is relatively unique. The most crucial diagnostic finding is the absence of INI-1 expression in tumor cells. Additionally, as discussed further in the Differential Diagnosis section below, is the typically negative immunolabeling of the tumor cells for S100, desmin, and CD31.[5][3][6][10]

Immunohistochemical Profile Summary

Positive labeling includes:

Negative labeling includes:

- INI-1/SMARCB1

- S100

- Desmin

- Factor VIII-related antigen

- Cytokeratin 7

History and Physical

Epithelioid sarcoma presents as a slow-growing, nodular lesion, most commonly involving the distal upper extremity, particularly the fingers, hands, and forearm. Lesions are usually painless and enlarge slowly, developing a multinodular appearance. Ulceration of the overlying skin and invasion of surrounding structures are common.[2][5][6] The lesion can arise in the dermis, subcutis, or deep fascia. Notably, obtaining a history of the lesion's onset, growth rate, any antecedent trauma, neurovascular deficit symptoms, and symptoms of pulmonary metastatic disease (eg, new onset of cough or hematemesis) is important.

Epithelioid sarcoma characteristically invades along fascial planes and tracks along tendons and aponeuroses, leading to a significantly wider area of involvement than is clinically visible.[2] The proximal variant of epithelioid sarcoma occurs more often in the perineal, pubic, genital, and truncal regions.[2][7] Masses can be large, up to 20 cm, especially in the proximal variant, but are often less than 5 cm in greatest dimension.[1][5][6]

A physical exam should focus on the size of the tumor, its relation to surrounding structures, invasion into surrounding structures, and any overlying skin changes. As epithelioid sarcoma has a high rate of lymph node metastases, which is unusual for soft tissue sarcomas, all draining lymph node basins should be examined.[2] A general physical evaluation, including a whole-body skin examination, pulmonary auscultation, and assessment of other potential sites of metastatic disease, is critical.

Evaluation

A tissue biopsy is necessary, as soft tissue swellings have many possible causes. Core needle biopsies are the preferred method. Based on clinical examination, biopsies should also be taken from any suspicious lymph nodes. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred diagnostic tool for most soft-tissue sarcomas, as it provides detailed images of the extent of tumor invasion into the surrounding fascial planes. An image-guided biopsy may be preferred for larger lesions with significant necrotic components, enabling targeted biopsies from more metabolically active areas. In some cases, incisional or excisional biopsies may be necessary. When surgical biopsies are performed, they should be oriented to incorporate them into any future surgical excision.

Epithelioid sarcoma is associated with a high rate of distant metastases, with recent studies suggesting a distant metastasis rate of up to 50%. The most common sites of metastases are the lungs, lymph nodes, and skin. As a result, staging imaging with a chest computed tomography (CT) scan is typically performed. For more extensive staging, fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scans or additional CT scans may be necessary, depending on the characteristics of the primary tumor.[11]

Treatment / Management

Wide excision is the treatment of choice for nonmetastatic epithelioid sarcoma. Although margins of 2 to 5 cm have been described, the extent of resection should be individualized, with every effort made to preserve limb function. Despite its propensity for metastasis, sentinel lymph node biopsy is not recommended in clinically node-negative patients. Lymph node dissection of the involved basin is indicated in patients with clinically positive lymph nodes. The surgical management of solitary in-transit metastases and isolated pulmonary metastases is controversial, and the lack of randomized clinical trials affects the available data. Metastasectomy may be indicated in certain situations.

Radiation therapy is often added to mitigate local recurrence; however, the indications for radiation therapy are relatively undefined.[12] Current indications for radiation therapy include patients with narrow margins, microscopically positive margins, local recurrence, and use as a palliative modality in patients with large tumors.[13] More recently, an inhibitor of enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2), Tazemetostat, has been approved for patients with unresectable or metastatic epithelioid sarcoma.[14]

Local recurrence rates of 40% to 60% have been reported, with a median time to recurrence of 1 to 2 years. However, recurrences have been reported as late as 20 years after the initial operation. As a result, close surveillance with cross-sectional imaging of the primary site and lungs is critical, typically with imaging studies every 6 months to 1 year.[15]

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnosing epithelioid sarcoma can be challenging due to its mixed mesenchymal and epithelial differentiation. This unique characteristic can cause the tumor to appear similar to various other reactive, benign, and malignant processes, making histologic diagnosis alone difficult. Immunohistochemical labeling may be used to confirm the diagnosis, although it is essential to consider other more common diagnostic entities with similar histologic and immunophenotypic characteristics. The most accurate diagnosis can be made by considering the appropriate clinical context, such as the presence of a soft tissue mass on the extremity of a young male, with immunohistochemical staining providing diagnostic support.

The differential diagnosis based on histomorphology generally includes reactive and benign lesions such as granulomatous diseases, nodular fasciitis, fibrohistiocytic lesions, fibromatosis, and tenosynovial giant cell tumors. Malignant lesions in the differential diagnosis include metastatic carcinoma, melanoma, synovial sarcoma, vascular neoplasms, spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST), and extrarenal rhabdoid tumor.[1][5][3][6]

The following is a summary of immunohistochemical stains for epithelioid sarcoma:

- CD34: Positive in half of epithelioid sarcoma (negative in synovial sarcoma and most carcinomas).

- Vimentin: Positive in epithelioid sarcoma (negative in many carcinomas, except notably endometrial and renal).

- INI-1: Complete loss is distinctive.

- CK7: Negative in epithelioid sarcoma (positive in synovial sarcoma).

- CK5/6 and p63: Negative in epithelioid sarcoma (positive in squamous cell carcinoma).

- S100: Negative in epithelioid sarcoma (positive in MPNST and many melanomas).

- CD31: Negative in epithelioid sarcoma, except in 1 documented case (positive in vascular lesions).[16]

- SALL4: Negative in 89% of epithelioid sarcoma (positive in 71% of malignant rhabdoid tumors).[17]

- ERG: Variably positive in epithelioid sarcoma (negative in all malignant rhabdoid tumors).[17]

- Vascular markers: ERG, FLI1, and D240 have been demonstrated in epithelioid sarcoma.[8][10]

Prognosis

Prognosis, as with most malignancies, is primarily determined by the clinical stage of the disease. Epithelioid sarcoma prognosis is most closely associated with tumor size, vascular invasion, resectability, and metastases.[6] Large tumor size and early metastases are independently associated with poor outcomes.[9] The proximal type is generally described as a more aggressive tumor; however, at least one study demonstrated no significant difference in overall survival between the proximal and usual types of epithelioid sarcoma.[2]

Gender, age at diagnosis, tumor site, size, and microscopic characteristics significantly impact prognosis. Female patients generally exhibit better outcomes than males. Distal lesions tend to have better outcomes compared to proximal ones. Presentation at an earlier age has better outcomes. Tumors larger than 2 cm in diameter, as well as those exhibiting necrosis and vascular invasion, are associated with poorer outcomes. 5-year overall survival rates typically range from 60% to 75%.[18]

Complications

Complications associated with epithelioid sarcoma are primarily categorized into those related to the primary disease, treatment-related secondary effects, and those caused by distant metastases. Localized lesion growth can damage surrounding tissues, nerves, blood vessels, and bones, leading to the destruction of the skin, underlying soft tissues, and skeletal structures. Metastases to lymph nodes, lungs, and skin can manifest with local symptoms. Furthermore, depending on the location of the initial tumor, surgical resection and radiation may result in complications.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Epithelioid sarcoma is a type of slow-growing soft tissue tumor that is frequently found in the upper extremities, predominantly affecting young men. This condition may present asymptomatically; therefore, patients should be encouraged to have any growths evaluated by a medical professional. Upon diagnosis confirmation, patients should receive counseling on available treatment options, including risks and benefits associated with each. They should also be educated on common posttreatment complications and concerning symptoms and instructed to report any concerning symptoms to their clinician promptly. Clinicians should discuss prognosis expectations and emphasize the necessity of long-term surveillance due to the potential for recurrent tumors, which can arise many years after initial treatment. Although preventive measures to lower the risk of developing this cancer are currently unknown, patients should be advised on the criticality of regular monitoring and adherence to scheduled follow-up appointments for imaging studies.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional healthcare team is crucial for improving health outcomes for patients with epithelioid sarcoma, which is a rare and aggressive type of sarcoma. The evaluating physician must maintain a high level of suspicion to ensure timely and accurate diagnosis, which includes obtaining appropriate imaging studies and biopsies. Treating these patients is complex and requires collaboration among surgeons, radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, physical therapists, radiologists, and various supportive departments. Effective care coordination necessitates these healthcare professionals to communicate and discuss cases in interprofessional settings, thereby facilitating joint decisions that enhance patient outcomes. Emphasizing patient-centered care principles ensures that decisions prioritize the patient's quality of life and functionality, thereby improving overall patient safety and team performance.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Enzinger FM. Epitheloid sarcoma. A sarcoma simulating a granuloma or a carcinoma. Cancer. 1970 Nov:26(5):1029-41 [PubMed PMID: 5476785]

de Visscher SA, van Ginkel RJ, Wobbes T, Veth RP, Ten Heuvel SE, Suurmeijer AJ, Hoekstra HJ. Epithelioid sarcoma: Still an only surgically curable disease. Cancer. 2006 Aug 1:107(3):606-12 [PubMed PMID: 16804932]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHollmann TJ, Hornick JL. INI1-deficient tumors: diagnostic features and molecular genetics. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2011 Oct:35(10):e47-63. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31822b325b. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21934399]

Modena P, Lualdi E, Facchinetti F, Galli L, Teixeira MR, Pilotti S, Sozzi G. SMARCB1/INI1 tumor suppressor gene is frequently inactivated in epithelioid sarcomas. Cancer research. 2005 May 15:65(10):4012-9 [PubMed PMID: 15899790]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFisher C. Epithelioid sarcoma of Enzinger. Advances in anatomic pathology. 2006 May:13(3):114-21 [PubMed PMID: 16778474]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChase DR, Enzinger FM. Epithelioid sarcoma. Diagnosis, prognostic indicators, and treatment. The American journal of surgical pathology. 1985 Apr:9(4):241-63 [PubMed PMID: 4014539]

Guillou L, Wadden C, Coindre JM, Krausz T, Fletcher CD. "Proximal-type" epithelioid sarcoma, a distinctive aggressive neoplasm showing rhabdoid features. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study of a series. The American journal of surgical pathology. 1997 Feb:21(2):130-46 [PubMed PMID: 9042279]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMiettinen M, Wang Z, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Abdullaev Z, Pack SD, Fetsch JF. ERG expression in epithelioid sarcoma: a diagnostic pitfall. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2013 Oct:37(10):1580-5. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31828de23a. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23774169]

Hasegawa T, Matsuno Y, Shimoda T, Umeda T, Yokoyama R, Hirohashi S. Proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 20 cases. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2001 Jul:14(7):655-63 [PubMed PMID: 11454997]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStockman DL, Hornick JL, Deavers MT, Lev DC, Lazar AJ, Wang WL. ERG and FLI1 protein expression in epithelioid sarcoma. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2014 Apr:27(4):496-501. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.161. Epub 2013 Sep 27 [PubMed PMID: 24072183]

Sobanko JF, Meijer L, Nigra TP. Epithelioid sarcoma: a review and update. The Journal of clinical and aesthetic dermatology. 2009 May:2(5):49-54 [PubMed PMID: 20729965]

Noujaim J, Thway K, Bajwa Z, Bajwa A, Maki RG, Jones RL, Keller C. Epithelioid Sarcoma: Opportunities for Biology-Driven Targeted Therapy. Frontiers in oncology. 2015:5():186. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00186. Epub 2015 Aug 17 [PubMed PMID: 26347853]

Callister MD, Ballo MT, Pisters PW, Patel SR, Feig BW, Pollock RE, Benjamin RS, Zagars GK. Epithelioid sarcoma: results of conservative surgery and radiotherapy. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2001 Oct 1:51(2):384-91 [PubMed PMID: 11567812]

Straining R, Eighmy W. Tazemetostat: EZH2 Inhibitor. Journal of the advanced practitioner in oncology. 2022 Mar:13(2):158-163. doi: 10.6004/jadpro.2022.13.2.7. Epub 2022 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 35369397]

Czarnecka AM, Sobczuk P, Kostrzanowski M, Spalek M, Chojnacka M, Szumera-Cieckiewicz A, Rutkowski P. Epithelioid Sarcoma-From Genetics to Clinical Practice. Cancers. 2020 Jul 29:12(8):. doi: 10.3390/cancers12082112. Epub 2020 Jul 29 [PubMed PMID: 32751241]

den Bakker MA, Flood SJ, Kliffen M. CD31 staining in epithelioid sarcoma. Virchows Archiv : an international journal of pathology. 2003 Jul:443(1):93-7 [PubMed PMID: 12743818]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKohashi K, Yamada Y, Hotokebuchi Y, Yamamoto H, Taguchi T, Iwamoto Y, Oda Y. ERG and SALL4 expressions in SMARCB1/INI1-deficient tumors: a useful tool for distinguishing epithelioid sarcoma from malignant rhabdoid tumor. Human pathology. 2015 Feb:46(2):225-30. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2014.10.010. Epub 2014 Nov 4 [PubMed PMID: 25479928]

Jawad MU, Extein J, Min ES, Scully SP. Prognostic factors for survival in patients with epithelioid sarcoma: 441 cases from the SEER database. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2009 Nov:467(11):2939-48. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0749-2. Epub 2009 Feb 18 [PubMed PMID: 19224301]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence