Introduction

The corneal bed and the anterior chamber are immune-privileged sites, but despite the relative immune privilege of the cornea as a transplanted tissue, the most common cause of corneal graft failure in all reports is allogeneic rejection. In first-time graft recipients with no vascularisation of the recipient's corneal bed, 2-year survival rates exceed 90%; this decreases to 35% to 70% in recipients with high-risk factors for rejection. In one-third of all corneal grafts fail, signs of a destructive attack by the immune system have been observed. A rejection episode results in a loss of donor endothelial cells, which are critical for the maintenance of corneal transparency.[1] As human endothelial cells do not repair by mitosis, the consequence is that donor corneal transparency is lost if cell density falls below the threshold necessary for the prevention of stromal swelling.

Endothelial decompensation results either from an irreversible episode of acute graft rejection or at an interval following one or more episodes of rejection, which have been reversed by therapy. Endothelial cells are thus the critical target in the allogeneic response.[2] While the reversal of acute graft rejection episodes does not present such challenges in the cornea as in other transplanted tissues, effective prophylaxis in corneal graft recipients identified at high risk of rejection is much less evidence-based.[2] Thus, the impact of graft rejection continues to justify a high priority in corneal research.[3]

Although the first successful penetrating corneal graft was reported in 1906, it took another half a century before the first description of the opacification of a previously clear corneal graft was published. Paufique named this event “maladie du greffon” (disease of the graft) and suggested that sensitization of the donor by the recipient is the cause.[4] This description followed previous experiments reported by Medawar, during which differences were observed between rabbit skin grafts of donor and recipient origin, giving rise to the term “histocompatibility.” Maumenee subsequently confirmed this suggestion in a rabbit model of corneal transplantation in which he showed that donor corneas could induce an immune reaction.[5] This development of corneal transplantation models in the rat and mouse-facilitated studies of rejection in inbred donor and recipient animals showed a wide range of investigative immunological reagents.[6]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Preoperative characteristics of the graft-recipient eye can be identified in many patients to indicate a significantly high risk of graft failure. Proposed graft-recipient corneas with two or more quadrants of deep vascularisation or one bearing a previously rejected graft that is inflamed at the time of transplantation are at a significantly higher risk of rejection.[7] There is less robust evidence in the published literature that grafts in children, large-diameter donor corneas, and the proximity of the donor cornea to the recipient limbus cause a higher risk.

More than one of these factors may exist in a patient. Furthermore, one or more of the above factors may predispose the patient to rejection due to additional clinical features that confer a significant risk of graft failure.[8] These additional complications include glaucoma or ocular surface disease. Clinicians must evaluate these preoperative clinical features carefully to decide whether to proceed with corneal transplantation.[9] Once transplantation is successfully completed, care must be taken to prevent postoperative events that lead to rejection, for example, vascularization of recipient cornea or graft wound, suture loosening, or graft infection.[10]

Epidemiology

In reports from large cohorts of corneal graft recipients, the proportion experiencing rejection at some stage post-transplant ranges from 18% to 21%. In those graft recipients in whom rejection occurs, reported rates of successful reversal of the rejection episode range from 50% to 90%.[11] Allograft rejection occurs most commonly in the second 6 months post-grafting, and it has been reported that more than 10% of the observed reactions can occur as late as four years after surgery. This data indicates that all corneal grafts need long-term surveillance and are at risk indefinitely. Epithelial rejection comprises approximately 2% of graft rejections.

Subepithelial rejections have an incidence of 1% and are the least common type. Endothelial rejection is the most common, with an incidence of 50%. The incidence of mixed rejection is approximately 30%. In deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty, the reported incidence of stromal immune rejection is 1-24%. As per the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) reports, the average incidence of primary graft failure in Descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK) is 5%, and the incidence of mean endothelial rejection rate is 10%.

As per the AAO report of 2017, the incidence of graft rejection in Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty was 0-5.9 %, with a mean of 1.9%. The incidence of primary and secondary graft failure was 1.7% and 2.2,% respectively. Jonas et al., in their analysis, found that approximately 14% has immunologic graft rejection secondary to loose sutures and vascularization preoperatively and postoperatively.[12]

Pathophysiology

The high success rate in corneal transplantation is possible because the cornea is an immune-privileged organ in the human body. The other factors contributing to success are avascularity and lack of lymphatics. The avascularity prevents infiltration by inflammatory cells and immune-responsive cells. In the absence of lymphatics, the foreign antigen presentation is also limited. Moreover, the number of MHC antigens expressed on the other tissues is comparatively less, thus further enhancing immune privilege.[13]

Graft Rejection

The specific immunological response of the host cornea to the donor corneal button/tissue is defined as corneal graft rejection. The diagnosis of graft rejection is made only when the graft has remained clear for at least 2 weeks after the corneal transplant. The challenge is to differentiate it from primary graft failure and the other caused by non-immunological graft failures. As per a detailed literature review, the incidence of graft rejection is maximum within the first 18 months and then reduces, although graft rejection has been reported even more than 20 years after the primary transplantation.[14]

Primary Graft Failure

It is the presence of corneal edema on the first postoperative day after corneal transplantation. The probable reasons are iatrogenic or surgical trauma, deficiency in storage, transport, or improperly stored tissue, and inherent deficiency in the tissue. As per the recommendations by American Eye Bank Association, the minimal endothelial count for the donor tissue should be 2000 cells/and the storage time should be less than 7 days.[15]

Histopathology

Descriptions of pathological features of corneal transplant rejection result from the examination of replaced grafts following irreversible failure.[16] These specimens illustrate late changes in end-stage corneal opacification, usually months following rejection treatment.[17] Characteristic findings in the stroma are vascularisation with mononuclear cell infiltration and keratocyte loss, few if any endothelial cells remain. Several studies have shown increased numbers of HLA class II positive cells infiltrating stroma in sections of rejected grafts.[18]

In penetrating keratoplasty, the rejection starts as a thin line adjacent to the limbal vessels and then migrates across the graft host junction. This line comprises lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils. This faint line can slowly progress to endothelial rejection in a few days to weeks.[19]

Epithelial Rejection

The epithelial rejection shows the leukocytes and lymphocytes when examined under light and electron microscope. A lot of disorganized cells can be observed on the graft.[20]

Subepithelial Rejection

Subepithelial rejection is caused by a deep-seated infiltrate and rejection by stromal keratocytes.[21]

Stromal Rejection

In hyperacute stromal rejection, there is a predominance of monocytes, fibroblasts, lymphocytes, and plasma cells external to endothelial capillaries. The stromal keratocyte architecture is altered due to lymphocyte infiltration. Capillary vessel formation is seen in the anterior and mid stroma with a predominance of immunoblast-like cells.[22]

Endothelial Rejection

Long and round cells with loss of cell junctions. Damage to the cells near the graft host junction and dense mononuclear infiltration resulting in replacement of damaged cells adjacent to the endothelium. Fibroblasts and altered endothelial cells form a sheet over the Descemet membrane.[12]

History and Physical

Patients with epithelial and stromal rejection may be asymptomatic or simply have mild ocular discomfort. In contrast, patients with endothelial rejection will usually present with visual disturbance and iritis symptoms. Epithelial rejection, diagnosed by a linear opacity stained with fluorescein, comprised up to 10% of all rejection episodes in one series and occurred on average three months after grafting.[23] Although dead donor epithelial cells are rapidly replaced by recipient epithelial cells, and no scarring occurs, this type of rejection reflects that the recipient is now sensitized to the donor and can progress to stromal and endothelial rejection. Stromal rejection is characterized by nummular subepithelial infiltrates identical to those found in adenovirus keratitis.[23]

If examined early after rejection symptoms begin, anterior chamber cell infiltration without flare or graft abnormality will be seen. When symptoms start later, the signs, in succession, are aggregated alloreactive cells adherent to graft endothelium, evident as keratic precipitates, endothelial line with precipitates, and localized edema corresponding to a rejection line or total graft edema. Visible graft precipitates on slit-lamp biomicroscopy imply focal and variable, but irreversible, endothelial cell loss, compromising endothelial pump function and resulting in stroma edema in those grafts with severe inflammation or low endothelial cell density before rejection onset.[24] Pachymetry helps detect an increase in edema and also deturgescence following the start of steroid treatment. One study found that next to the preoperative diagnosis, graft thickness during rejection, as objectively measured by pachymetry, is a prognostic sign for reversibility of a rejection episode. Risk factors for significant endothelial cell loss are a delay in initiating anti-rejection treatment for more than one day and recipient age older than 60 years.[25]

On detailed slit lamp examination, the typical clinical signs of corneal graft rejection are rejection lines in the epithelium, subepithelial focal infiltrates, corneal edema, patchy stromal infiltrate, Khodadoust endothelial line, presence of keratic precipitates, neovascularization. A corneal graft is labeled immunological failed if the rejection episode doesn't clear even after 2 months of intensive treatment.[20]

Risk Factors

Preoperative

Donor Corneal

- Antigen load of donor

- HLA and ABO incompatibility

- Duration of tissue storage

- Technique and nature of corneal button cutting

- Ultraviolet rays pre-treatment ( protective effect)

- Vaccination (Influenza, COVID-19)[26]

Host Corneal

- Vascularization (low risk, medium risk, and high risk)

- Low risk- No vascularity

- Medium risk- Upto 2 quadrant vascularization

- High risk- 3 or more quadrant vascularization

- Previous failed graft or graft rejection (excessive immune response)

- Regraft

- Ocular surface diseases (e.g., Chemical injury, inflammatory dry eyes, mucous membrane pemphigoid, Steven-Johnson syndrome, ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, seventh nerve palsy)

- Persistent ocular inflammation (e.g., Viral keratitis)

- Young age (robust immune system)

- Previous anterior segment surgery

- Uncontrolled glaucoma

- Peripheral anterior synechiae

- ABO incompatibility

- Herpetic eye disease

- Pilocarpine

- Anterior chamber associated immune deviation (ACAID)

- Excimer laser phototherapeutic keratectomy

- Interstitial keratitis

- Trauma

- Large graft[27]

Intraoperative

- Large graft

- Eccentric graft

- Peripheral anterior synechiae

- Bilateral corneal transplantation

- Penetrating graft > Lamellar graft

- Previous anterior segment surgery

- Limbal graft

- Suture removal[7]

Postoperative

- Loose suture

- Exposed suture knots

- Blepharitis

- Entropion

- Trichiasis

- Vascularization

- Posterior synechiae

- Peripheral anterior synechiae

- Secondary glaucoma

- Suture removal

- Steroid compliance[28]

Penetrating Keratoplasty (PKP)

Host

- Preoperatively inflamed eyeball

- Corneal vascularization of more than 2 quadrants

- Corneal stromal vascularization

- Young age at transplantation

- Regraft ( two or more have high risk)

- Previous ocular surgery

- Peripheral anterior synechiae

- Posterior synechiae

- Prior history of ocular inflammatory disease

- Prior history of antiglaucoma medication use[29]

Mechanical

- Large corneal graft

- Eccentric graft

- Old therapeutic keratoplasty

- Loose sutures

- Suture removal

- Suture infiltrate

- Suture vascularization[30]

Descemet Stripping Endothelial Keratoplasty (DSEK)

- The risk factors of DSEK rejection include

- Shallow anterior chamber

- Previous history of glaucoma

- Steroid-induced glaucoma

- African -American ancestry

- Peripheral anterior synechiae

- Iris atrophy

- Floppy iris syndrome

- Aphakia[31]

Clinical Features of Various Types of Graft Rejection

|

S. No |

Type of Rejection |

Clinical Presentation |

|

1. |

Epithelial |

Epithelial rejection line starting from graft host junction and extending to donor graft, quiet eye, no corneal edema, no anterior chamber reaction. The time of onset is usually 3 months (1-13 months). The line stains with fluorescein or Rose Bengal. The suture infiltrates can also be seen, which progress centripetally known as Kay's dots. The average time of resolution is 1 to several weeks. Epithelial rejection is usually self-limiting, but some cases can have a persistent epithelial defect. Epithelial rejection rings have also been reported[32] |

|

2 |

Hyperacute stromal |

Circumciliary congestion, patchy stromal infiltrates, stromal edema, and stromal haze, The patients can present with peripheral stromal haze. The infiltrate can also be seen as an abscess at the graft host junction more confined to the limits of the graft. The mild form is treatable. The severe form leads to necrosis, descemetocele, and frank perforation. Crystalline deposits in the stroma have also been reported.[33]

|

|

3 |

Chronic stromal |

There is a predominance of subepithelial infiltrates on the graft and is noticed late, usually between 2-5 months. They are usually present below the Bowman's layer in the donor graft. The rejection shows a prompt response to steroids.[34]

|

|

4 |

Stromal and Endothelial rejection in a regraft |

It starts from the host cornea, diffuse cells, and flare, but there is an absence of an endothelial rejection line. In the early stages, the stomal and endothelial components can be differentiated, but the differentiation is lost as the rejection progresses. The rejection needs prolonged steroid therapy.[35] |

|

5 |

Chronic focal |

The patient presents with pain, redness, and blurred vision. The time of onset can vary from 8 months to 35 years. Epithelial and stromal edema, KPs at the back of the cornea, Khodadoust line, mild anterior chamber activity. This is more common in young patients, and the rejection rate is inversely proportional to the extent of vascularity.[36] |

Unique Characteristics of Stromal Graft Rejection

- The rejection band migrates away from the vascularized cornea.

- The rejection episode is followed by infiltration of blood vessels deep in the stroma

- Occasionally it can masquerade as a corneal abscess in densely vascularized corneas.

- The stromal haze involves the host cornea the areas adjacent to the corneal vascularization[37]

Classification of Endothelial Rejection

- Possible – Graft edema builds up slowly, but there are no signs of inflammation or rejection

- Probable- Signs of inflammation present with anterior chamber reaction, KPs on endothelium, graft edema but no endothelial rejection line.

- Definite- All the above clinical features along with endothelial rejection line[37]

Characteristics of Graft Rejection in a Regraft

- Usually noticed within two weeks of regraft (immune sensitization)

- The rejection episode is quiet and usually seen after 1 month of clear cornea

- There is a higher risk and high incidence of graft failure in a previously grafted eye

- The higher the graft number higher is the risk of rejection

- Absence of endothelial rejection line despite the uveitic episode

- Early involvement of the margin of the host cornea

- Intensive and prolonged corticosteroid therapy is needed to reverse an episode[38]

Evaluation

Visual Acuity

Snellen's best corrected and uncorrected visual acuity must be recorded on each visit which is a good indicator of graft clarity or graft rejection. Visual acuity is a valuable tool to monitor the response to treatment.[39]

Intraocular Pressure

Secondary glaucoma is a vital complication post corneal transplantation. On every visit, intraocular pressure must be recorded. The preferred method would be a non-contact tonometer to avoid contact with the transplanted tissue and prevent any incidence of graft rejection or dehiscence.[40]

Retinoscopy and Refraction

This is important to know the best-corrected visual, the spherical and cylindrical add needed, the amount of astigmatism induced due to sutures, and the spherical equivalent.[41]

Scheimpflug Imaging

This is important in cases with high astigmatism to know the steeper and flat axis of astigmatism. This also helps in planning suture removal to reduce astigmatism.[42]

Specular Microscopy

Useful in all cases preoperatively to know the donor endothelial count and viability. This is also helpful to assess the endothelial status in postoperative endothelial keratoplasty patients.[43]

Anterior Segment Optical Coherence Tomography

Useful to assess the depth of opacity, any areas of thinning, and graft attachment in DSEK and DMEK.[44]

Fluorescein Staining

To rule out any epithelial defect, dry eyes, and ocular surface staining.[45]

B Scan

This is helpful to assess the retinal status in cases with small pupils, graft rejection, and unexplained visual loss in a clear graft.[46]

Macular Optical Coherence Tomography

This investigation will be helpful to rule out cystoid macular edema and epiretinal membrane.[47]

Treatment / Management

The objective of treatment is to reverse the rejection episode at the earliest possible time, minimize donor endothelial cell loss, and preserve graft function. With the anatomical advantage that corneal transplants are superficial, intensive administration of a topical corticosteroid, such as dexamethasone 0.1%, successfully reverses most endothelial rejection episodes. In most cases in which topical steroid fails to reverse rejection, it is likely to be due to delay in recognition and initiation of treatment resulting in significant donor endothelial cell loss. In others, failure to reverse rejection may be due to the failure of topical steroids to reverse effector components of the allogeneic response.[11]

In respect of additional systemic steroids, a single dose of intravenous methylprednisolone was more effective than oral steroids in patients with endothelial rejection who presented within eight days of onset. The second pulse of intravenous methylprednisolone at 24 or 48 hours gave no benefit compared to a single dose at the initial diagnosis. However, a subsequent randomized trial demonstrated no significant benefit of intravenous methylprednisolone in addition to a topical steroid in respect of graft survival or interval to a subsequent rejection episode within a 2-year follow-up period. In the same study, endothelial rejection was reversed in 33 of 36 patients treated, indicating that steroid-resistant rejection is uncommon. Other studies examining the efficacy of topical or oral cyclosporin administered with intravenous steroids have reported similar outcomes, with irreversible rejection in a small proportion of patients.[48](A1)

The best treatment for cornea graft rejection is treating and preventing an episode of immune-mediated graft rejection. The prevention can be divided into preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative risk factors for graft rejection.

Preoperative

The aim is to reduce the antigenic difference between the host and donor cornea and minimize the antigenic load of the donor tissue.

Intraoperative

The intraoperative factors contributing to graft rejection are decentred graft, suture knots exposed, loose sutures, graft host junction not well opposed, and less expertise in performing the procedure.

Postoperative

The postoperative factors important in managing corneal graft rejection are timely and regular follow-up and reducing the host immune response to the donor graft. Timely steroid administration and suture management in decreasing suture-related vascularization and rejection.

Management

The management of corneal graft rejection rests on prompt detection and aggressive steroid therapy. It is important to counsel the patient to present immediately if any symptoms of graft rejection like pain, redness, and decreased vision are noticed. It is highly important to know the varied drug options available to manage corneal graft rejection.[49]

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are the drugs of choice and are considered the gold standard in the management of corneal graft rejection because of their numerous beneficial properties.[49]

Topical Corticosteroids

Topical steroids are preferred due to good anterior chamber penetration and effective immunosuppressive properties. The steroid regimen varies from center to center. The commonly followed regimen is hourly for 2-3 days, then 6 times for 15 days, 4/3/2/1 times for 3 months each. Some Ophthalmologists used 2 hourly for 15 days after an hourly regimen for 3 days. An hourly regimen must be followed in acute graft rejection until the signs of reversal are observed or graft rejection is arrested. Topical steroid therapy must be supplemented with intravenous (IV) steroids. Once the IV therapy is complete, oral steroids must be given. The tapering regimen will depend on the response to treatment. The drug of choice can be 1 % prednisolone or 0.1% dexamethasone.[50](A1)

Systemic Corticosteroids

The systemic corticosteroids can be administered orally as well as intravenous therapy. It should be supplemented with topical treatment. The oral prednisolone should be initiated in a higher dose than usual dosage of around 60-80 mg daily and then tapered based on the response for 6-8 weeks.[51](A1)

Intravenous Corticosteroids

The recommended drug is methylprednisolone (MP). Pulse IV therapy is given with methylprednisolone 500 mg in 150 ml of saline two times per day for 3 days. Pulse IVMP causes transient lymphopenia, which peaks at 4-6 hours and lasts for 48 hours. The anti-inflammatory activity of IVMP lasts for 4-7 days. Another innovative approach of intravitreal triamcinolone acetate administration for chronic graft failure has also been described.[52]

Steroid Therapy Based on Risk Factor Assessment for Corneal Graft Rejection

|

S. No |

Risk factor |

Preoperative therapy |

Postoperative therapy |

|

1 |

Normal risk of rejection |

None |

Topical steroids |

|

2 |

High risk of rejection |

Topical steroids |

Topical steroids (long duration, slow taper) |

|

3 |

High risk of rejection (old graft rejection |

Topical steroids |

Topical steroids + oral steroids (long duration, slow taper) |

Management of Various Graft Rejections

|

S. No |

Type of Graft Rejection |

Topical therapy |

Systemic therapy |

|

1 |

Epithelial graft rejection |

Aggressive steroid therapy |

- |

|

2 |

Subepithelial graft rejection |

Aggressive steroid therapy |

- |

|

3 |

Stromal graft rejection |

Aggressive steroid therapy |

IVMP |

|

4 |

Endothelial graft rejection |

Aggressive steroid therapy, cyclosporine A, cycloplegics |

IVMP |

|

5 |

Mixed graft rejection (combined) |

Aggressive steroid therapy, cycloplegics |

IVMP + cycloplegics with maintenance therapy |

|

6 |

Rejection in a failed graft |

Aggressive steroid therapy, cycloplegics |

IVMP + cycloplegics with maintenance therapy |

|

7 |

Acute corneal edema |

Aggressive steroid therapy |

- |

|

8 |

Gradual corneal edema |

Nonaggressive steroid therapy |

- |

Cytotoxic Agents

Azathioprine

The most common drug implicated is azathioprine, which inhibits purine synthesis. As this is a phase-specific inhibitor of the cell cycle, the drug is helpful only in the early stages of graft rejection. The dose of azathioprine is 1-2 mg/kg/day orally and is given in combination with topical corticosteroids. The combination prevents the need for systemic steroids and, in turn, reduces steroid-induced side effects. The patient needs to be monitored with complete hemogram and liver function tests. Azathioprine is known to cause side effects like bone marrow suppression, thrombocytopenia, toxicity, and risk of cancer; hence its use is limited in graft rejection.[53]

Cyclosporin A

This is an immunosuppressive agent derived from fungus tolypocladium inflatum gans. This agent is also helpful in the early stages of graft rejection.[54](A1)

Topical Cyclosporin A

Topical cyclosporine A is used as a 0.5% formulation in high-risk patients. It reduces the incidence of allograft immune-mediated rejection.[54](A1)

Systemic Cyclosporin A

This is again implicated for high-risk patients of corneal graft rejection. The recommended dose is 15 mg/kg/day for 2 days later, half dosage for 2 days, and then adjusted to reduce blood levels of 100-200 mg/l for 6 months to prevent or reverse the acute graft rejection episode. The patients should be monitored with liver and renal function tests.[55]

Combined Corticosteroids and Cyclosporin A Therapy

This is an effective therapy for treating acute graft rejection and preventing future episodes.

Newer Immunomodulators

Tacrolimus

This is 100 times more potent than cyclosporine, also called FK-506. Tacrolimus is given in a dose of 0.16 mg/kg/day for preventing immune-mediated allograft rejection. FK-506 is a biodegradable polymer and is also available as an anterior chamber implant that is found to be effective for treating graft rejection.[56](B3)

Rapamycin

This drug is considered to be more potent than cyclosporine and tacrolimus. It is lipophilic, has better corneal penetration, and can be used for corneal graft rejection.[57](B3)

15-Deoxyspergualin (DSG)

This drug has been reported with many side effects and is still experimental.[58]

Other Newer Experimental Drugs

Differential Diagnosis

Staging

Grading of Post Keratoplasty Neovascularization[66]

|

S. No |

Neovascularization Grade |

Blood Vessels |

|

1 |

0 |

Avascular- No vessels |

|

2 |

1+ |

Vascularization up to 2 quadrants (recipient bed only) |

|

3 |

2+ |

Vascularization in 3-4 quadrants (recipient bed only) |

|

4 |

3+ |

Vascularization at graft host junction in 1-2 quadrants |

|

5 |

4+ |

Vascularization at graft host junction in 3-4 quadrants |

|

6 |

5+ |

Vascularization in the stroma of graft at the periphery in 1-2 quadrants |

|

7 |

6+ |

Vascularization in the stroma of graft at the periphery in 3-4 quadrants |

|

8 |

7+ |

Vascularization in the central stroma of graft in 1-2 quadrants |

|

9 |

8+ |

Vascularization in the central stroma of graft in 3-4 quadrants |

Scoring of Corneal Clarity in Corneal Graft Rejection[66]

|

S. No |

Score |

Corneal Graft Clarity |

|

1 |

0 |

Clear graft |

|

2 |

1+ |

Minimal superficial corneal opacity |

|

3 |

2+ |

Mild stromal scar with iris and pupil details visible |

|

4 |

3+ |

Moderate stromal scarring with iris details hazy only pupil visible |

|

5 |

4+ |

Dense stromal scar with anterior chamber visible |

|

6 |

5+ |

Total corneal scar with no view of intraocular structures |

Prognosis

The prognosis in corneal grafts depends on several factors such as meticulous preoperative case selection, preoperative timing, storage and transport of donor graft, intraoperative surgical technique, meticulous postoperative examination, early detection, classification of rejection, and prompt, timely intervention with corticosteroids. The visual prognosis is governed by graft host junction opposition, centration, clarity, and graft survival postoperatively. Approximately 75% of endothelial rejections can be reversed with an excellent visual outcome. Fine and Stain, in their analysis, documented that about 50% of vascularized grafts and 66% of grafts without vascularization resulting in rejection can be reversed.[67]

The prognosis diminishes as the number of repeat grafts increases. The prognosis is also poor in young patients due to the high incidence of graft rejection as they have a robust immune system. The prognosis in regrafts depends on the extent of vascularization in the failed graft. The graft prognosis was described by Sano et al. by grading the vascularization in graft and scoring the corneal graft rejection. Apart from this, the prognosis is also governed by patient education, compliance to medications, time of presentation after a rejection episode, the financial status of the patient, timely and regular follow-up. Various factors have been implicated, including HLA and ABO donor matching, but no conclusive guideline exists.[14]

Complications

- Failed graft

- Persistent epithelial defect

- Infective keratitis

- Corneal melt

- Pseudocornea

- Descemetoceles

- Corneal scarring

- Band shaped keratopathy

- Urrets Zavalia syndrome

- Secondary glaucoma

- Angle-closure glaucoma

- Recurrent uveitis

- Occlusio pupillae

- Seclusio pupillae

- Festooned pupil

- Cystoid macular edema

- Endophthalmitis

- Panophthalmitis

- Ciliary shutdown

- Phthisis

- Permanent blindness

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Any patient presenting to the clinic with signs of graft rejection should be admitted. The patient should be started on intravenous steroids 100 mg dexamethasone or 500 mg prednisolone in 150 ml of 5% dextrose solution two times for 3 days along with topical steroids 1% prednisolone of 0.1% dexamethasone 2 hourly for 3 days and later 6 times for 15 days, 4/3/2/1 times 3 months each based on the clinical response. Adjuvant drugs like 5% homatropine 2 times per day to relieve ciliary spasm and prevent the formation of synechiae and 0.5% timolol two times per day to prevent the development of secondary glaucoma.[67]

Patients with regraft should be treated on similar lines. The patients must be educated regarding the importance of steroids in graft survival. They must be explained about the ill effects of noncompliance to treatment and the side effects of steroids overuse. The patient should be given a follow-up chart or a discharge sheet to understand the medication schedule and next follow-up date. The patient must be evaluated for graft clarity, visual acuity, intraocular pressure, and any other side effects related to surgery or medications on every visit.[68]

Consultations

Any patient who has undergone corneal transplantation previously and presents with pain, redness, and photophobia should be treated as an emergency by the ophthalmologist. The patient should be evaluated meticulously to determine the signs of graft rejection. A cornea and ocular surface specialist should ideally assess all cases to label the type of rejection and decide on treatment. In case of any suspected secondary retinal complications, the patient should be evaluated by a vitreoretinal specialist to decide on treatment. Patients with a corneal graft having associated cataract should be dealt by a cataract an IOL specialist for cataract surgery and perfect visual outcome in a transplanted eye.[69]

Deterrence and Patient Education

All patients undergoing corneal transplantation should be explained the risk and benefits of the same preoperatively. The patients should be explained about the chances of immune rejection and the importance of time and regular instillation of steroids. The patients should be educated about the symptoms and signs of graft rejection, and if the same occurs, they should be told to report immediately to a cornea specialist for treatment. The patients should also be explained regarding the quality of vision, chances of graft clarity, and impact of corneal transplantation on the patient's quality of life.[19]

Pearls and Other Issues

In vascularised organ allotransplantation, there is robust evidence supporting HLA matching of donor and recipient, with the data of Opelz and others demonstrating stratification of the risk of rejection according to the number of class I and especially class II mismatches. HLA matching is routine, internationally, in cadaveric renal and other organ transplantation. Contrastingly, in corneal transplantation, in some countries, donor and recipient matching is routinely done for recipients who have a high risk of HLA class I and class II rejection, while in other countries, no matching takes place. Roelen suggested a benefit for HLA-A and HLA-B matching of high-risk corneal allograft recipients was that primed, donor-specific cytotoxic T cells were present in rejected corneas, but absent in donors with good graft function. However, the benefit of histocompatibility matching in corneal transplantation has been disputed.[70]

It is less apparent than the benefit for solid organ grafts, even in corneal recipients at a perceived high risk of graft rejection. Two large prospective studies on HLA-A, HLA-B, or HLA-DR antigen matching of high-risk recipients have reported divergent findings. The Collaborative Corneal Transplant Studies Research Group reported that matching of these antigens did not decrease the risk of corneal graft failure secondary to rejection.[71] In contrast, the Corneal Transplant Follow-up Study found there was an increased risk of graft rejection with the mismatch of HLA class I antigens (relative risk 1.27 per mismatch), but decreasing the risk of rejection with HLA-DR mismatches (relative risk 0.58 per mismatch) in high-risk patients. This study, therefore, supported matching at HLA-A and HLA-B but not HLA-DR. The possible benefit of planned HLA-DR mismatching in a setting of known class I histocompatibility is being investigated in an ongoing prospective trial.[72]

In 1996, a randomized, although retrospective study revealed the beneficial effect of DRB1 matching in recipients at high risk because of vascularization and/or retransplantation. Subsequently, a beneficial effect of HLA-DPB1 matching in high-risk corneal transplantation with a significantly higher rate of 1-year, rejection-free, graft survival compared to those without matching was shown. Therefore, in corneal transplantation, the effect of HLA matching is less than clear, and the data are ambiguous for class II matching. The resolution of this clinically important issue is not simple. In contrast to solid organs, results of cornea matching are likely to be influenced by the following facts:

- Allorecognition is predominantly by the indirect pathway in most patients and minor transplantation antigens.

- Allorecognition is shown to significantly affect graft survival in untreated rodent recipients and is present by the indirect pathway.

- Allorecognition remains unmatched in HLA-matched recipients.[73]

It is also worth noting here that the effects of HLA matching on corneal graft outcomes have not yet been investigated in the setting of systemic immunosuppression prophylaxis. Studies in solid organ transplantation have shown that more effective rejection prophylaxis can override an HLA-matching effect in unsensitized recipients.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An ophthalmologist manages corneal graft rejection, and the follow up done by an ophthalmic nurse. The nurse also provides patient education. The interprofessional team includes a pharmacist to review prescriptions, check for drug-drug interactions, and provide patient and family education. The objective of treatment is to reverse the rejection episode at the earliest possible time, minimize donor endothelial cell loss, and preserve graft function. With the anatomical advantage that corneal transplants are superficial, intensive administration of a topical corticosteroid, such as dexamethasone 0.1%, treatment is successful in reversing most endothelial rejection episodes.

In most cases in which topical steroids fail to reverse rejection, it is likely to be due to delay in recognition and initiation of treatment resulting in significant donor endothelial cell loss. In others, failure to reverse rejection may be due to the failure of topical steroids to reverse effector components of the allogeneic response. The outcomes in patients treated promptly are good, but delays in treatment can lead to loss of the graft and injury to the underlying tissues. Close follow-up by the team following a corneal transplant is mandatory. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

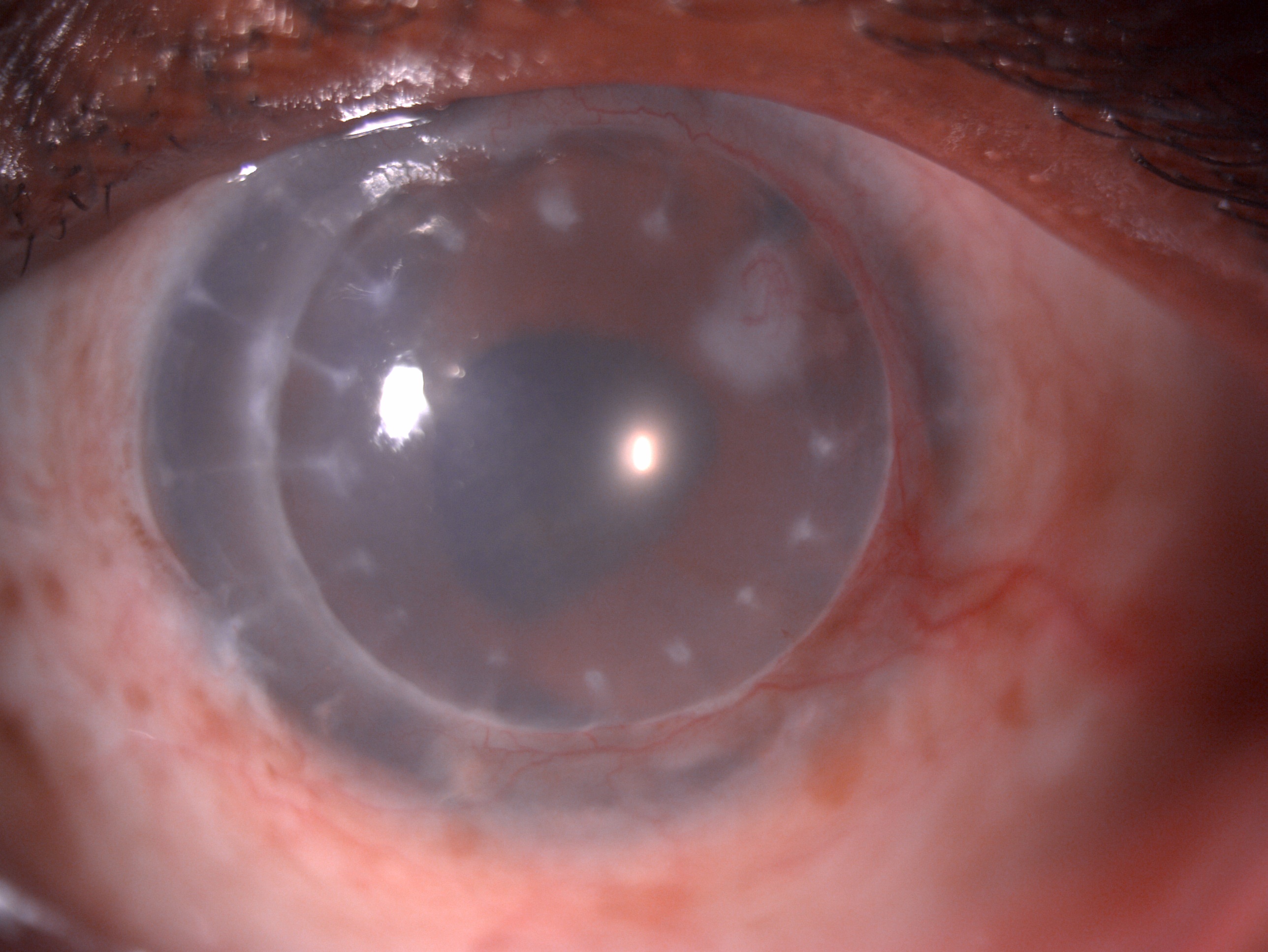

Digital slit lamp image of the patient's left eye depicting mild circumciliary congestion, well opposed graft host junction, stromal edema, suture marks, stromal scar with ghost vessels at 2 o'clock adjacent to the graft host junction. Close observation reveals deep vascularization of 2 quadrants from 12 to 6 o'clock infiltrating the graft host junction suggestive of a case of chronic stromal rejection Contributed by Dr. Bharat Gurnani, MBBS, DNB, FCRS, FICO, MRCS Ed, MNAMS

References

Niederkorn JY, Larkin DF. Immune privilege of corneal allografts. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2010 Jun:18(3):162-71. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2010.486100. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20482389]

Amano S. [Transplantation of corneal endothelial cells]. Nippon Ganka Gakkai zasshi. 2002 Dec:106(12):805-35; discussion 836 [PubMed PMID: 12610838]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCatapano J, Fung SSM, Halliday W, Jobst C, Cheyne D, Ho ES, Zuker RM, Borschel GH, Ali A. Treatment of neurotrophic keratopathy with minimally invasive corneal neurotisation: long-term clinical outcomes and evidence of corneal reinnervation. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2019 Dec:103(12):1724-1731. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-313042. Epub 2019 Feb 15 [PubMed PMID: 30770356]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHussen MS,Belete GT, Knowledge and Attitude toward Eye Donation among Adults, Northwest Ethiopia: A Community-based, Cross-sectional Study. Middle East African journal of ophthalmology. 2018 Jul-Dec; [PubMed PMID: 30765949]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSharifi R,Yang Y,Adibnia Y,Dohlman CH,Chodosh J,Gonzalez-Andrades M, Finding an Optimal Corneal Xenograft Using Comparative Analysis of Corneal Matrix Proteins Across Species. Scientific reports. 2019 Feb 12; [PubMed PMID: 30755666]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTanaka TS, Hood CT, Kriegel MF, Niziol L, Soong HK. Long-term outcomes of penetrating keratoplasty for corneal complications of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2019 Dec:103(12):1710-1715. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-313602. Epub 2019 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 30733209]

Di Zazzo A, Kheirkhah A, Abud TB, Goyal S, Dana R. Management of high-risk corneal transplantation. Survey of ophthalmology. 2017 Nov-Dec:62(6):816-827. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2016.12.010. Epub 2016 Dec 22 [PubMed PMID: 28012874]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBarraquer RI, Pareja-Aricò L, Gómez-Benlloch A, Michael R. Risk factors for graft failure after penetrating keratoplasty. Medicine. 2019 Apr:98(17):e15274. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000015274. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31027083]

Gracitelli CPB, Ferrar PV, Pereira CAP, Hirai FE, de Freitas D. A case of recurrent keratitis caused by Paecilomyces lilacinus and treated by voriconazole. Arquivos brasileiros de oftalmologia. 2019 Mar-Apr:82(2):152-154. doi: 10.5935/0004-2749.20190031. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30726410]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGadhvi KA, Romano V, Fernández-Vega Cueto L, Aiello F, Day AC, Allan BD. Deep Anterior Lamellar Keratoplasty for Keratoconus: Multisurgeon Results. American journal of ophthalmology. 2019 May:201():54-62. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2019.01.022. Epub 2019 Feb 2 [PubMed PMID: 30721690]

Armitage WJ, Goodchild C, Griffin MD, Gunn DJ, Hjortdal J, Lohan P, Murphy CC, Pleyer U, Ritter T, Tole DM, Vabres B. High-risk Corneal Transplantation: Recent Developments and Future Possibilities. Transplantation. 2019 Dec:103(12):2468-2478. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002938. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31765363]

Jonas JB, Rank RM, Budde WM. Immunologic graft reactions after allogenic penetrating keratoplasty. American journal of ophthalmology. 2002 Apr:133(4):437-43 [PubMed PMID: 11931775]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAmouzegar A, Chauhan SK, Dana R. Alloimmunity and Tolerance in Corneal Transplantation. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950). 2016 May 15:196(10):3983-91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600251. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27183635]

Qazi Y, Hamrah P. Corneal Allograft Rejection: Immunopathogenesis to Therapeutics. Journal of clinical & cellular immunology. 2013 Nov 20:2013(Suppl 9):. pii: 006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24634796]

Gain P, Jullienne R, He Z, Aldossary M, Acquart S, Cognasse F, Thuret G. Global Survey of Corneal Transplantation and Eye Banking. JAMA ophthalmology. 2016 Feb:134(2):167-73. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.4776. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26633035]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLiu J, Li L, Li X. Effectiveness of Cryopreserved Amniotic Membrane Transplantation in Corneal Ulceration: A Meta-Analysis. Cornea. 2019 Apr:38(4):454-462. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001866. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30702468]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCampbell JDM, Ahmad S, Agrawal A, Bienek C, Atkinson A, Mcgowan NWA, Kaye S, Mantry S, Ramaesh K, Glover A, Pelly J, MacRury C, MacDonald M, Hargreaves E, Barry J, Drain J, Cuthbertson B, Nerurkar L, Downing I, Fraser AR, Turner ML, Dhillon B. Allogeneic Ex Vivo Expanded Corneal Epithelial Stem Cell Transplantation: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Stem cells translational medicine. 2019 Apr:8(4):323-331. doi: 10.1002/sctm.18-0140. Epub 2019 Jan 28 [PubMed PMID: 30688407]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLin PA,Tseng SH,Huang YH, Corneal Transplantation From Donors With Hepatitis B: Preliminary Results. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2019 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 30676375]

Panda A, Vanathi M, Kumar A, Dash Y, Priya S. Corneal graft rejection. Survey of ophthalmology. 2007 Jul-Aug:52(4):375-96 [PubMed PMID: 17574064]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAlldredge OC,Krachmer JH, Clinical types of corneal transplant rejection. Their manifestations, frequency, preoperative correlates, and treatment. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1981 Apr [PubMed PMID: 7013739]

Krachmer JH, Alldredge OC. Subepithelial infiltrates: a probable sign of corneal transplant rejection. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1978 Dec:96(12):2234-7 [PubMed PMID: 363109]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBartels MC, Otten HG, van Gelderen BE, Van der Lelij A. Influence of HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-DR matching on rejection of random corneal grafts using corneal tissue for retrospective DNA HLA typing. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2001 Nov:85(11):1341-6 [PubMed PMID: 11673303]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWatson SL, Tuft SJ, Dart JK. Patterns of rejection after deep lamellar keratoplasty. Ophthalmology. 2006 Apr:113(4):556-60 [PubMed PMID: 16581417]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBüyüktepe TÇ, Yalçındağ N. Cytomegalovirus Endotheliitis After Penetrating Keratoplasty. Turkish journal of ophthalmology. 2020 Oct 30:50(5):304-307. doi: 10.4274/tjo.galenos.2020.47568. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33342198]

Ho Wang Yin G,Sampo M,Soare S,Hoffart L, [Visual acuity, pachymetry and corneal density after 5% sodium chloride treatment in corneal edema after surgery]. Journal francais d'ophtalmologie. 2015 Dec [PubMed PMID: 26547229]

Niederkorn JY,Callanan D,Ross JR, Prevention of the induction of allospecific cytotoxic T lymphocyte and delayed-type hypersensitivity responses by ultraviolet irradiation of corneal allografts. Transplantation. 1990 Aug [PubMed PMID: 2382295]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKhodadoust AA,Karnema Y, Corneal grafts in the second eye. Cornea. 1984 [PubMed PMID: 6399229]

Christo CG, van Rooij J, Geerards AJ, Remeijer L, Beekhuis WH. Suture-related complications following keratoplasty: a 5-year retrospective study. Cornea. 2001 Nov:20(8):816-9 [PubMed PMID: 11685058]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceZhai LY,Zhang XR,Liu H,Ma Y,Xu HC, Observation of topical tacrolimus on high-risk penetrating keratoplasty patients: a randomized clinical trial study. Eye (London, England). 2020 Sep [PubMed PMID: 31784702]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBafna RK, Kalra N, Asif MI, Lata S, Rathod A, Balaji A, Sharma N. Suturing large therapeutic corneal grafts based on donor size: A simplified technique for the novice corneal surgeon. European journal of ophthalmology. 2021 May:31(3):1417-1421. doi: 10.1177/1120672120974285. Epub 2020 Nov 23 [PubMed PMID: 33228422]

Thompson JM,Truong AH,Stern HD,Djalilian A,Cortina MS,Tu EY,Johnson P,Verdier DD,Rafol L,Lubeck D,Spektor T,Jorgensen C,Rubenstein JB,Majmudar PA,Talati R,Basti S,Feder R,Sugar A,Mian SI,Balasubramanian N,Sandhu J,Gaynes BI,Bouchard CS, A Multicenter Study Evaluating the Risk Factors and Outcomes of Repeat Descemet Stripping Endothelial Keratoplasty. Cornea. 2019 Feb [PubMed PMID: 30615600]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDandona L,Naduvilath TJ,Janarthanan M,Rao GN, Causes of corneal graft failure in India. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 1998 Sep [PubMed PMID: 10085627]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKhodadoust AA, Silverstein AM. Transplantation and rejection of individual cell layers of the cornea. Investigative ophthalmology. 1969 Apr:8(2):180-95 [PubMed PMID: 4887869]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSmolin G,Goodman D, Corneal graft reaction. International ophthalmology clinics. 1988 Spring [PubMed PMID: 3279003]

Peeler JS,Niederkorn JY, Effect of Langerhans' cells on cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to major and minor alloantigens expressed on heterotopic corneal allografts. Transplantation proceedings. 1987 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 3547821]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBoisjoly HM, Bernard PM, Dubé I, Laughrea PA, Bazin R, Bernier J. Effect of factors unrelated to tissue matching on corneal transplant endothelial rejection. American journal of ophthalmology. 1989 Jun 15:107(6):647-54 [PubMed PMID: 2658619]

Streilein JW,Bergstresser PR, Ia antigens and epidermal Langerhans cells. Transplantation. 1980 Nov [PubMed PMID: 7006163]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceD'Amaro J, Volker-Dieben HJ, Kruit PJ, de Lange P, Schipper R. Influence of pretransplant sensitization on the survival of corneal allografts. Transplantation proceedings. 1991 Feb:23(1 Pt 1):368-72 [PubMed PMID: 1990555]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBrahma A,Ennis F,Harper R,Ridgway A,Tullo A, Visual function after penetrating keratoplasty for keratoconus: a prospective longitudinal evaluation. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2000 Jan [PubMed PMID: 10611101]

Dada T, Aggarwal A, Minudath KB, Vanathi M, Choudhary S, Gupta V, Sihota R, Panda A. Post-penetrating keratoplasty glaucoma. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2008 Jul-Aug:56(4):269-77 [PubMed PMID: 18579984]

Tuft SJ,Gregory W, Long-term refraction and keratometry after penetrating keratoplasty for keratoconus. Cornea. 1995 Nov [PubMed PMID: 8575185]

Kwon RO,Price MO,Price FW Jr,Ambrósio R Jr,Belin MW, Pentacam characterization of corneas with Fuchs dystrophy treated with Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Journal of refractive surgery (Thorofare, N.J. : 1995). 2010 Dec [PubMed PMID: 20166622]

Morris E,Kirwan JF,Sujatha S,Rostron CK, Corneal endothelial specular microscopy following deep lamellar keratoplasty with lyophilised tissue. Eye (London, England). 1998; [PubMed PMID: 9850251]

Lim LS,Aung HT,Aung T,Tan DT, Corneal imaging with anterior segment optical coherence tomography for lamellar keratoplasty procedures. American journal of ophthalmology. 2008 Jan [PubMed PMID: 18028862]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChen M, Miki M, Lin S, Yung Choi S. Sodium Fluorescein Staining of the Cornea for the Diagnosis of Dry Eye: A Comparison of Three Eye Solutions. Medical hypothesis, discovery & innovation ophthalmology journal. 2017 Winter:6(4):105-109 [PubMed PMID: 29560363]

Dessì G, Lahuerta EF, Puce FG, Mendoza LH, Stefanini T, Rosenberg I, Del Prato A, Perinetti M, Villa A. Role of B-scan ocular ultrasound as an adjuvant for the clinical assessment of eyeball diseases: a pictorial essay. Journal of ultrasound. 2015 Sep:18(3):265-77. doi: 10.1007/s40477-014-0153-y. Epub 2014 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 26261467]

Acar BT,Muftuoglu O,Acar S, Comparison of macular thickness measured by optical coherence tomography after deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty and penetrating keratoplasty. American journal of ophthalmology. 2011 Nov; [PubMed PMID: 21794841]

Hill JC, Ivey A. Corticosteroids in corneal graft rejection: double versus single pulse therapy. Cornea. 1994 Sep:13(5):383-8 [PubMed PMID: 7995059]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHill JC, Maske R, Watson PG. The use of a single pulse of intravenous methylprednisolone in the treatment of corneal graft rejection. A preliminary report. Eye (London, England). 1991:5 ( Pt 4)():420-4 [PubMed PMID: 1743357]

Nguyen NX,Seitz B,Martus P,Langenbucher A,Cursiefen C, Long-term topical steroid treatment improves graft survival following normal-risk penetrating keratoplasty. American journal of ophthalmology. 2007 Aug [PubMed PMID: 17659972]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHill JC,Maske R,Watson P, Corticosteroids in corneal graft rejection. Oral versus single pulse therapy. Ophthalmology. 1991 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 2023754]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceYoung AL, Rao SK, Cheng LL, Wong AK, Leung AT, Lam DS. Combined intravenous pulse methylprednisolone and oral cyclosporine A in the treatment of corneal graft rejection: 5-year experience. Eye (London, England). 2002 May:16(3):304-8 [PubMed PMID: 12032722]

Coster DJ, Williams KA. Immunosuppression for corneal transplantation and treatment of graft rejection. Transplantation proceedings. 1989 Feb:21(1 Pt 3):3125-6 [PubMed PMID: 2650437]

Poon A,Constantinou M,Lamoureux E,Taylor HR, Topical Cyclosporin A in the treatment of acute graft rejection: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology. 2008 Jul [PubMed PMID: 18939344]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceZiaei M,Ziaei F,Manzouri B, Systemic cyclosporine and corneal transplantation. International ophthalmology. 2016 Feb [PubMed PMID: 26463642]

Rath T, Tacrolimus in transplant rejection. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 2013 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 23228138]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDong Y,Huang YF,Wang LQ,Chen B, [Experimental study on the effects of rapamycin in prevention of rat corneal allograft rejection]. [Zhonghua yan ke za zhi] Chinese journal of ophthalmology. 2005 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 16271181]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDiehl R, Ferrara F, Müller C, Dreyer AY, McLeod DD, Fricke S, Boltze J. Immunosuppression for in vivo research: state-of-the-art protocols and experimental approaches. Cellular & molecular immunology. 2017 Feb:14(2):146-179. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2016.39. Epub 2016 Oct 10 [PubMed PMID: 27721455]

Szaflik JP,Major J,Izdebska J,Lao M,Szaflik J, Systemic immunosuppression with mycophenolate mofetil to prevent corneal graft rejection after high-risk penetrating keratoplasty: a 2-year follow-up study. Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology = Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 2016 Feb [PubMed PMID: 26553197]

Ma D, Mellon J, Niederkorn JY. Oral immunisation as a strategy for enhancing corneal allograft survival. The British journal of ophthalmology. 1997 Sep:81(9):778-84 [PubMed PMID: 9422933]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRocher N,Behar-Cohen F,Pournaras JA,Naud MC,Jeanny JC,Jonet L,Bourges JL, Effects of rat anti-VEGF antibody in a rat model of corneal graft rejection by topical and subconjunctival routes. Molecular vision. 2011 Jan 11; [PubMed PMID: 21245949]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchäcke H, Berger M, Rehwinkel H, Asadullah K. Selective glucocorticoid receptor agonists (SEGRAs): novel ligands with an improved therapeutic index. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2007 Sep 15:275(1-2):109-17 [PubMed PMID: 17630119]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGurnani B, Kaur K, Tripathy K. Is there a genetic link between Keratoconus and Fuch's endothelial corneal dystrophy? Medical hypotheses. 2021 Dec:157():110699. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2021.110699. Epub 2021 Oct 9 [PubMed PMID: 34666260]

Gurnani B, Kaur K. Pythium Keratitis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 34424645]

Gurnani B, Christy J, Narayana S, Rajkumar P, Kaur K, Gubert J. Retrospective multifactorial analysis of Pythium keratitis and review of literature. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2021 May:69(5):1095-1101. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1808_20. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33913840]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSano Y, Ksander BR, Streilein JW. Fate of orthotopic corneal allografts in eyes that cannot support anterior chamber-associated immune deviation induction. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 1995 Oct:36(11):2176-85 [PubMed PMID: 7558710]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBersudsky V,Blum-Hareuveni T,Rehany U,Rumelt S, The profile of repeated corneal transplantation. Ophthalmology. 2001 Mar [PubMed PMID: 11237899]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLiu D, Ahmet A, Ward L, Krishnamoorthy P, Mandelcorn ED, Leigh R, Brown JP, Cohen A, Kim H. A practical guide to the monitoring and management of the complications of systemic corticosteroid therapy. Allergy, asthma, and clinical immunology : official journal of the Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2013 Aug 15:9(1):30. doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-9-30. Epub 2013 Aug 15 [PubMed PMID: 23947590]

Vora GK, Ciolino JB. Corneal allograft reaction associated with nonocular inflammation. Digital journal of ophthalmology : DJO. 2014:20(2):29-31. doi: 10.5693/djo.02.2013.12.001. Epub 2014 May 7 [PubMed PMID: 25097462]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHoward CA, Fernandez-Vina MA, Appelbaum FR, Confer DL, Devine SM, Horowitz MM, Mendizabal A, Laport GG, Pasquini MC, Spellman SR. Recommendations for donor human leukocyte antigen assessment and matching for allogeneic stem cell transplantation: consensus opinion of the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network (BMT CTN). Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2015 Jan:21(1):4-7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.09.017. Epub 2014 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 25278457]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSugar J. The Collaborative Corneal Transplantation Studies. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1992 Nov:110(11):1517-8 [PubMed PMID: 1444902]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVail A, Gore SM, Bradley BA, Easty DL, Rogers CA, Armitage WJ. Conclusions of the corneal transplant follow up study. Collaborating Surgeons. The British journal of ophthalmology. 1997 Aug:81(8):631-6 [PubMed PMID: 9349147]

Munkhbat B, Hagihara M, Sato T, Tsuchida F, Sato K, Shimazaki J, Tsubota K, Tsuji K. Association between HLA-DPB1 matching and 1-year rejection-free graft survival in high-risk corneal transplantation. Transplantation. 1997 Apr 15:63(7):1011-6 [PubMed PMID: 9112356]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence