Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Adductor Canal (Subsartorial Canal, Hunter Canal)

Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Adductor Canal (Subsartorial Canal, Hunter Canal)

Introduction

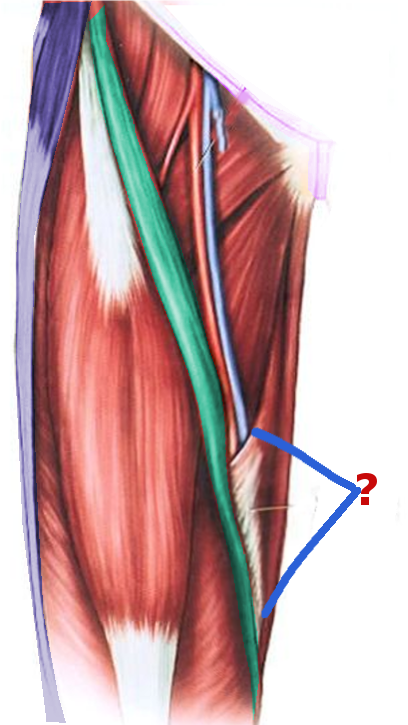

The adductor canal (AC), also known as the subsartorial or Hunter canal, is a conical musculoaponeurotic tunnel passing through the distal aspect of the thigh's middle third (see Image. Adductor Canal). This region is a passageway for several neurovascular structures from the femoral triangle to the adductor hiatus.[1][2]

Major structures passing through the AC include the superficial femoral artery, femoral vein, and saphenous nerve. The nerve to the vastus medialis is also often mentioned as traversing the AC, but some authors challenge this claim. The AC is a clinically relevant anatomical landmark, as disease and trauma can involve this region. The AC is also an increasingly common nerve block site for knee, ankle, and foot surgeries.[3][4][5][6] This review discusses AC's anatomy and clinical relevance.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Structure

The AC is a neurovascular tunnel located distal to the anteromedial thigh. The AC's average length is reportedly between 8.5 and 11.5 cm, depending on sex. The borders of this region include the following:

- Proximal border - The AC begins at the femoral triangle's apex, where the medial borders of the sartorius and adductor longus cross. Some sources cite the femoral triangle apex as the adductor longus' lateral border. However, recent studies maintain that the apex is the medial border of the adductor longus muscle.

- Distal border - The AC ends at the adductor hiatus, the largest of 5 fibrous openings within the adductor magnus. The superficial femoral artery becomes the popliteal artery as it passes distally through the adductor hiatus.

- Anterolateral border - The vastus medialis muscle lies in the AC's anterolateral margin.

- Posterolateral border - The AC is bounded by the adductor longus and magnus muscles posterolaterally.

- Medial border - The vastoadductor membrane (VAM) occupies the AC's medial edge. The VAM is also sometimes referred to as the AC's “roof.”. The sartorius muscle is superficial to the VAM.

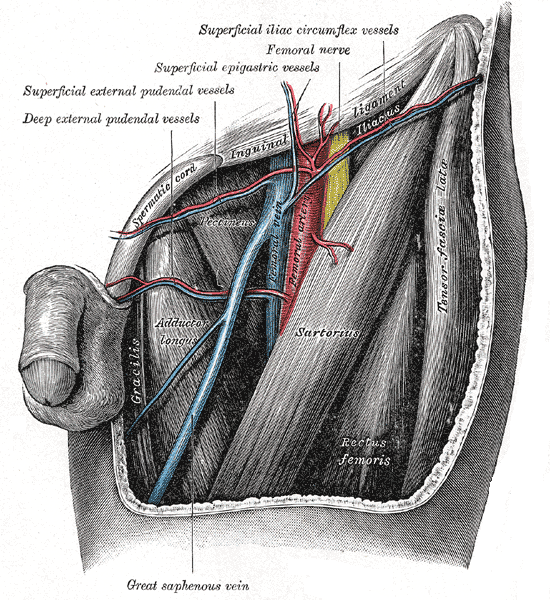

Surface landmarks and ultrasound can help locate the AC. The midpoint between the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) and the patellar base corresponds to the femoral triangle. The AC is located a few centimeters distal to this region. For reference, the following are the borders of the femoral or Scarpa triangle (see Image. Femoral Triangle Structures):

- Proximal border - inguinal ligament

- Lateral border - medial border of sartorius

- Medial border - medial border of adductor longus

- Floor - iliopsoas, pectineus, adductor longus, and adductor brevis muscles

- Apex - the intersection between the medial borders of the sartorius and adductor longus muscles

Published literature regarding the location of the AC's roof and medial border is inconsistent. Some sources name the AC's medial border as the sartorius muscle, with the canal located deep to this muscle and the muscle's span determining the AC's limits. However, the VAM lies deep to the sartorius muscle. The true AC is roofed and bordered medially by the VAM.

The space between the VAM and sartorius muscle is a plane called the "subsartorial space" or "subsartorial compartment." This designation can cause confusion, as the AC or Hunter canal is sometimes called the "subsartorial canal." The distinction is important because the true AC and the subsartorial space, which is superficial to the VAM, contain different nerve groups.[7][8]

Function

The AC transmits neurovascular structures from the femoral triangle proximally to the popliteal fossa distally. The AC maintains anatomic continuity between the 2 compartments.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The AC houses the superficial femoral artery and femoral vein. The superficial femoral artery originates from the femoral artery and delivers blood to the lower leg. The femoral vein is the proximal continuation of the popliteal vein, which drains the deep leg veins.

Proximal to the AC, the femoral artery gives off a branch called the "deep femoral artery" ("deep artery of the thigh" or "profunda femoris") and continues distally as the superficial femoral artery. The superficial femoral artery travels from the femoral triangle into the AC. The superficial femoral artery passes from the AC distally through the adductor hiatus in the adductor magnus, where it becomes the popliteal artery.[9]

The popliteal vein becomes the femoral vein as it ascends through the adductor hiatus. The femoral vein receives multiple minor tributaries in the adductor hiatus. The femoral vein eventually joins with the deep femoral and great saphenous veins to become the common femoral vein. Some sources use the name “superficial femoral vein” instead of “femoral vein,” but this designation is inaccurate. The vein is not superficial, though it can become a source of confusion as it courses along with the superficial femoral artery.[10]

Nerves

The saphenous nerve exits the femoral triangle's apex and enters the AC immediately lateral to the femoral artery. The saphenous nerve travels through the AC until it diverges from the femoral artery distally. The saphenous nerve exits between the sartorius and gracilis muscles.

The nerve to the vastus medialis was presumed previously to travel within the AC. However, this claim has been disputed, with other authors reporting that the NVM travels through the subsartorial space superficial to the VAM and deep to the sartorius muscle. The subsartorial space also houses the subsartorial plexus, formed by the medial cutaneous nerve of the thigh, saphenous nerve, and anterior branch of the obturator nerve.

Muscles

The table below summarizes key information about the muscles bordering the AC.

| Muscle | Origin | Insertion | Innervation | Function |

| Adductor longus [11] | Anterior aspect of the pubic bone | Linea aspera of the femur | Obturator nerve | Adducts the thigh |

| Adductor magnus [12] |

Adductor portion: inferior pubic and ischial rami Hamstrings region: ischial tuberosity |

Adductor part: gluteal tuberosity, linea aspera, medial supracondylar line Hamstrings portion: adductor tubercle of femur |

Adductor portion: Obturator nerve Hamstrings part: tibial part of sciatic nerve |

Adductor part: adducts and flexes thigh Hamstrings region: adducts and extends thigh |

| Sartorius [13] | Anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) |

Superior medial aspect of the tibial shaft Joins with the gracilis and semitendinosus tendons to form the pes anserinus. |

Femoral nerve | Hip flexion, external hip rotation, knee flexion |

| Vastus medialis [14] | Inferior aspect of the intertrochanteric line and medial aspect of linea aspera | Medial border and base of the patella | Femoral nerve | Knee extension, stabilization of the patella |

Surgical Considerations

Peripheral nerve blocks are increasingly becoming more common in postoperative pain management. An ideal block provides adequate analgesia while maintaining motor function. An AC block (ACB) entails local anesthesia injection into the AC to manage pain during knee, ankle, and foot surgery. Performing the ACB is guided by knowledge of the AC's anatomy.

The human knee receives innervation from anterior and posterior sensory nerve groups. A properly performed AC block anesthetizes the anterior sensory nerve group without affecting the motor nerves. The AC block can be combined with another regional block targeting the posterior nerve group. Sparing the motor nerves during knee surgery, for example, a total knee arthroplasty (TKA), accelerates postoperative ambulation and improves recovery.

Multiple studies demonstrated that “estimating” the location of the AC often resulted in a femoral triangle block (FTB). An FTB is not motor-sparing because it often leads to quadriceps weakness, which may be inferior to an ACB in some clinical situations.

Clinical Significance

The structures passing through the AC are susceptible to multiple pathologies, which include the following:

- Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) - a common manifestation of atherosclerosis. PAD is an obstruction in arteries other than the cerebral and coronary vessels. The proximal popliteal and superficial femoral arteries are the lower extremity sites most frequently affected by atherosclerosis. The superficial femoral artery is the second most common site of femoral artery aneurysm (about 14% of cases).[15]

- AC compression syndrome (ACCS) - an extremely rare cause of lower extremity arterial insufficiency. This condition generally affects young, healthy, and physically active individuals. ACCS is non-atherosclerotic, though chronic and repeated superficial femoral artery compression in the AC can produce the condition. The exact cause of the compression remains unidentified due to the paucity of information. Reports indicate that some cases are due to anomalous embryologic musculotendinous fibrous bands. The bands are thought to arise from the adductor magnus and become symptomatic when this muscle or the vastus medialis hypertrophies. The treatment is surgery.[16]

- Venous disease - isolated deep venous thrombosis (DVT) in the AC is rare and more likely to coexist with DVTs in other locations.[17] Uhl and Gillot hypothesized that femoral vein compression and venous valve dysfunction within the AC might contribute to lower extremity venous stasis. However, no additional studies support this hypothesis.[18]

Diagnosing and treating AC conditions involve a thorough clinical evaluation, which may include physical examination and imaging tests. Specialized nerve conduction studies help identify nerve lesions.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Femoral Triangle Structures. This anterior view shows the femoral artery, vein and nerve, and the deep external pudendal vessels, superficial external pudendal vessels, superficial epigastric vessels, and superficial iliac circumflex nerve.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Adductor Canal. This anterior view shows the superficial femoral artery (red) and femoral vein passing through the adductor or Hunter canal (marked by "?"). The borders of this region include the femoral triangle's apex (proximal), adductor hiatus (distal), vastus medialis (anterolateral), adductor longus and magnus (posterolateral), and vastoadductor membrane (medial).

Image courtesy S Bhimji MD

References

Thiayagarajan MK, Kumar SV, Venkatesh S. An Exact Localization of Adductor Canal and Its Clinical Significance: A Cadaveric Study. Anesthesia, essays and researches. 2019 Apr-Jun:13(2):284-286. doi: 10.4103/aer.AER_35_19. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31198246]

Burckett-St Laurant D, Peng P, Girón Arango L, Niazi AU, Chan VW, Agur A, Perlas A. The Nerves of the Adductor Canal and the Innervation of the Knee: An Anatomic Study. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2016 May-Jun:41(3):321-7. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000389. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27015545]

Vora MU, Nicholas TA, Kassel CA, Grant SA. Adductor canal block for knee surgical procedures: review article. Journal of clinical anesthesia. 2016 Dec:35():295-303. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.08.021. Epub 2016 Oct 11 [PubMed PMID: 27871547]

Wong WY, Bjørn S, Strid JM, Børglum J, Bendtsen TF. Defining the Location of the Adductor Canal Using Ultrasound. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2017 Mar/Apr:42(2):241-245. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000539. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28002228]

Menon D, Onida S, Davies AH. Overview of arterial pathology related to repetitive trauma in athletes. Journal of vascular surgery. 2019 Aug:70(2):641-650. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2019.02.002. Epub 2019 May 18 [PubMed PMID: 31113722]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKasapis C, Gurm HS. Current approach to the diagnosis and treatment of femoral-popliteal arterial disease. A systematic review. Current cardiology reviews. 2009 Nov:5(4):296-311. doi: 10.2174/157340309789317823. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21037847]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBendtsen TF, Moriggl B, Chan V, Børglum J. The Optimal Analgesic Block for Total Knee Arthroplasty. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2016 Nov/Dec:41(6):711-719 [PubMed PMID: 27685346]

Panchamia JK, Niesen AD, Amundson AW. Adductor Canal Versus Femoral Triangle: Let Us All Get on the Same Page. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2018 Sep:127(3):e50. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000003570. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29905612]

Swift H, Bordoni B. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Femoral Artery. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30855850]

Black CM. Anatomy and physiology of the lower-extremity deep and superficial veins. Techniques in vascular and interventional radiology. 2014 Jun:17(2):68-73. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2014.02.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24840960]

Launico MV, Sinkler MA, Nallamothu SV. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Femoral Muscles. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29763184]

Jeno SH, Launico MV, Schindler GS. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Thigh Adductor Magnus Muscle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30521263]

Walters BB, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Thigh Sartorius Muscle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422484]

Khan A, Arain A. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Anterior Thigh Muscles. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30860696]

Lawrence PF, Harlander-Locke MP, Oderich GS, Humphries MD, Landry GJ, Ballard JL, Abularrage CJ, Vascular Low-Frequency Disease Consortium. The current management of isolated degenerative femoral artery aneurysms is too aggressive for their natural history. Journal of vascular surgery. 2014 Feb:59(2):343-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.08.090. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24461859]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceZhou Y, Ryer EJ, Garvin RP, Irvan JL, Elmore JR. Adductor canal compression syndrome in an 18-year-old female patient leading to acute critical limb ischemia: A case report. International journal of surgery case reports. 2017:37():113-118. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2017.06.030. Epub 2017 Jun 17 [PubMed PMID: 28654852]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCogo A, Lensing AW, Prandoni P, Hirsh J. Distribution of thrombosis in patients with symptomatic deep vein thrombosis. Implications for simplifying the diagnostic process with compression ultrasound. Archives of internal medicine. 1993 Dec 27:153(24):2777-80 [PubMed PMID: 8257253]

Uhl JF, Gillot C. Anatomy of the Hunter's canal and its role in the venous outlet syndrome of the lower limb. Phlebology. 2015 Oct:30(9):604-11. doi: 10.1177/0268355514551086. Epub 2014 Sep 10 [PubMed PMID: 25209386]