Introduction

Lymphadenopathy, or adenopathy, is a common abnormal finding during the physical exam in general medical practice. Patients and physicians have varying degrees of associated anxiety with the finding of lymphadenopathy, as a small number of cases can be caused by neoplasms or infections of consequence, for example, HIV or tuberculosis. However, it is generally recognized that most localized and generalized lymphadenopathy is of benign, self-limited etiology. A clear understanding of lymph node function, location, description, and the etiologies of their enlargement is important in clinical decisions regarding which cases need rapid and aggressive workup and which need only be observed.[1][2][3]

The lymph node functions as an antigen filter for the body's reticuloendothelial system. It consists of a multi-layered sinus that sequentially exposes B-cell lymphocytes, T-cell lymphocytes, and macrophages to an afferent extracellular fluid. In this way, the immune system can recognize and react to foreign proteins and mount an immune response or sequester these proteins as appropriate. In this reaction, there is some multiplication of the responding resistant cell line; thus, the node increases in size. It is generally held that a node size is considered enlarged when it is more significant than 1 cm. However, the reality is that "normal" and "enlarged" criteria vary depending on the node's location and the patient's age. For example, children younger than 10 have more hypertrophic immune systems, and nodes up to 2 cm can be considered normal in some clinical situations. However, an epitrochlear node above 0.5 cm is deemed pathological in an adult.

The lymphadenopathy's pattern, distribution, and quality can provide much clinical information in the diagnostic process. Lymphadenopathy occurs in 2 patterns: generalized and localized. Generalized lymphadenopathy entails lymphadenopathy in 2 or more non-contiguous locations. Localized adenopathy occurs in contiguous groupings of lymph nodes. Lymph nodes are distributed in discrete anatomical areas, and their enlargement reflects the lymphatic drainage of their location. The nodes may be tender or non-tender, fixed or mobile, discreet or "matted" together. Concomitant symptomatology and the epidemiology of the patient and the illness provide further diagnostic cues. A thorough history of prodromal illness, fever, chills, night sweats, weight loss, and localizing symptoms can be very revealing. Additionally, the demographic particulars of the patient, including age, gender, exposure to infectious disease, toxins, medications, and habits, may provide further cues.

As evidenced above, the critical step in evaluation for adenopathy is a careful history and focused physical exam. The patient's clinical presentation determines the extent of the history and physical. For example, a patient with posterior cervical adenopathy, sore throat, and tremendous fatigue needs only a careful history, cursory examination, and a mono test. In contrast, a person with generalized lymphadenopathy and fatigue would require more extensive investigation. Generally, most lymphadenopathy is localized (some site a 3:1 ratio), with the majority represented in the head and neck region (again, some site a 3:1 ratio). It is also accepted that all generalized lymphadenopathy merits clinical evaluation, and the presence of "matted lymphadenopathy" strongly indicates significant pathology.Examination of the patient's history, physical examination, and the demographic in which they fall can allow the patient to be placed into 1 of several different accepted algorithms for workup of lymphadenopathy. Using these cues and selecting the correct arm of the algorithm allows for a fairly rapid and cost-effective diagnosis of lymphadenopathy, including determining when it is safe to observe.[4][5][6]

Algorithmic Analysis of Lymphadenopathy

After a history and physical examination are completed, lymphadenopathy is placed into 3 categories:

- "Diagnostic" such as strep pharyngitis or upper respiratory tract disease, in which case the course of action is to treat the condition.

- "Suggestive" such as mononucleosis lymphoma or HIV, wherein the history and physical strongly suggestive diagnosis-specific testing is performed, and if positive, the action is to treat the condition.

- "Unexplained" where the lymphadenopathy is divided into generalized lymphadenopathy and localized lymphadenopathy.

For unexplained localized lymphadenopathy, a review of history, a regional exam, and epidemiological clues are used to separate patients into lower (no risk of malignancy or serious disease) versus higher risk for serious disease or malignancy categories. Suppose the patient is at no risk for malignancy or serious illness. In that case, the reasonable course is to observe the patient for 3 to 4 weeks to see if the lymphadenopathy resolves or improves. In this case, the clinician is safely cleared to follow the patient. If the lymphadenopathy does not resolve or improve, the next step is to obtain a biopsy. If the patient is judged to have a risk for malignancy or serious illness, the procedure is to proceed immediately to biopsy.

For unexplained generalized lymphadenopathy, the key to diagnosis is a history to evaluate for suspected causes. The initial search would be questioning for a mononucleosis-type syndrome evidenced by fever, atypical lymphocytosis, and malaise. Included in these differentials would be Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, toxoplasmosis, and (especially in the case of a flu-like illness and her rash) the initial stages of an HIV infection. The second step in evaluating unexplained generalized lymphadenopathy involves carefully reviewing epidemiological cues. Included in the epidemiological cues would be:

- Infectious disease exposure

- Animal exposure

- Insect bites

- Recent travel

- Complete medication history

- Personal habits: smoking, consumption of alcohol, consumption of drugs- pay special attention to a history of IVTA, high-risk sexual behavior

- Consumption of under-cooked food/untreated water [7][8]

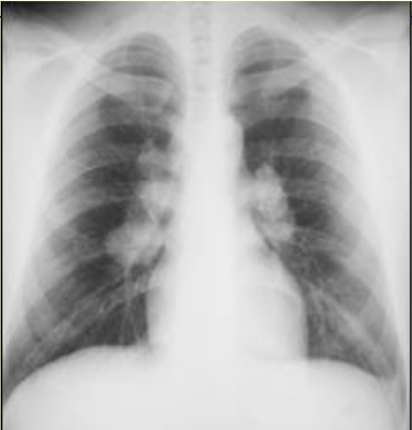

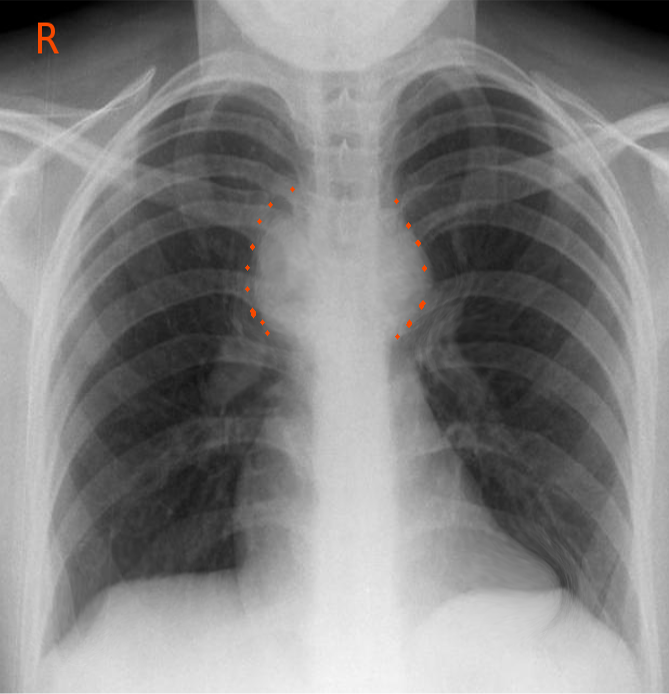

Although there is no "cookbook" for the laboratory evaluation of generalized unexplained lymphadenopathy, the initial steps are to obtain a complete blood count (CBC) with a manual differential and EBV serology. If non-diagnostic, the next steps would be PPD placement, RPR, chest x-ray, ANA, hepatitis B surface antigen, and HIV test (see Image. Mediastinal Adenopathy). Again, if any of the above are positive, appropriate treatment can be initiated. In the presence of negative serological examinations, radiological examinations, and or significant symptomology, a biopsy of the abnormal node is the gold standard for diagnosis.[9][10][11][12]Statistics concerning lymphadenopathy are inaccurate as the great majority of lymphadenopathy is caused by a non-reportable illness and thus not reported or taken into account. This results in a statistical bias, or skew, toward the reportable causes of lymphadenopathy: malignancies, HIV, tuberculosis, and sexually transmitted infections. Citations in the recent literature for general medical practice indicate that less than 1% of people with lymphadenopathy have malignant disease, most often due to leukemia in younger children, Hodgkin disease in adolescence, non-Hodgkin disease, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia in adults. It has been reported the general prevalence of malignancy is 0.4% in patients under 40 years and around 4% in those older than 40 years of age seen in a primary care setting. It is reported that the prevalence rate of neoplastic disease rises to nearly 20% in referral centers and rises to 50% or more in patients with initial risk factors.[13]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of lymphadenopathy includes the following:

- Infectious disease

- Neoplasm

- Inflammatory disease

- Autoimmune disease

- Inborn metabolic storage disorder

- Exposure to toxic/medication [7][14]

Infectious disease can be viral, bacterial, mycobacterial, fungal, or parasitic etiology:

- Viral etiologies of lymphadenopathy include HIV, mononucleosis caused by EBV or CMV, roseola, HSV, varicella, and adenovirus.

- Bacterial etiologies of lymphadenopathy include Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Salmonella, Syphilis, and Yersinia.

- Mycobacterial etiology of lymphadenopathy includes tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium intracellular.

- Fungal etiology of lymphadenopathy includes coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, and Candida.

- Parasitic etiology of lymphadenopathy includes toxoplasmosis, Chagas, and many ectoparasites.

- Neoplastic causes of lymphadenopathy include both primary malignancies and metastatic malignancies: Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, neuroblastoma, pediatric acute myelocytic leukemia, rhabdomyosarcoma, metastatic carcinoma of the lung, metastatic carcinoma of the viscera of the gastrointestinal tract, metastatic breast cancer, and metastatic thyroid cancer and metastatic renal cancer.

- Autoimmune disease causes of lymphadenopathy include sarcoidosis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, serum sickness, and systemic lupus erythematosus.

- Exposures to toxins and medications that are common causes of lymphadenopathy include allopurinol, atenolol, captopril, carbamazepine, many cephalosporins, gold, hydralazine, penicillin, phenytoin, primidone, para methylamine, quinidine, the sulfonamides, and sulindac. Lifestyle exposures to alcohol, ultraviolet radiation, and tobacco can cause cancers with secondary lymphadenopathy.

- Inborn metabolic storage disorders (including Niemann-Pick disease and Gaucher disease) are possible additional causes of lymphadenopathy [15][16][17][18][17]

Epidemiology

Broad generalities can safely be made about the epidemiology of lymphadenopathy.[19][20][21] First, generalized and localized lymphadenopathies are equally distributed without regard to gender. Second, lymphadenopathy is more prevalent in the pediatric population than in the adult population, secondary to the more significant number of viral infections. It would follow that most of the time, lymphadenopathy in the pediatric population is of less consequence, secondary to the prevalence of viral and bacterial infections in that age group. Three-quarters of all lymphadenopathy observed are localized; of those three-quarters, half are localized to the head and neck area. All remaining localized lymphadenopathy is found in the inguinal area, and the remaining lymphadenopathy is located in the axilla in the supraclavicular area. Of note, the differential diagnosis of lymphadenopathy changes significantly with the patient's age. Third, the patient's location and circumstances are very revealing, as well as lymphadenopathy. For example, in the developing world (sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, Indian subcontinent), exposure to parasites, HIV, and miliary tuberculosis are far more likely to be causes of generalized lymphadenopathy than in the United States and Europe. Whereas, Epstein-Barr virus, streptococcal pharyngitis, and some neoplastic processes are more likely candidates to cause lymphadenopathy in the United States and the remainder of the localized industrial world. An exposure history is significant for diagnosis.

- Exposure to blood and blood-borne products either through transfusion, unsafe sexual practices, intravenous drug abuse, or vocation

- Exposure to infectious disease, whether it be travel, in the workplace, or the home

- Medication exposure-prescription, nonprescription, or supplements

- Exposure to animal-borne illness either via pets or the workplace

- Exposure to arthropod bites [22]

Pathophysiology

Lymphatic fluid represents the totality of the body's interstitial fluid, and the lymphatic channels conduct this fluid and label antigens with antigen-presenting cells. As the lymphatic channels progress, they converge regionally to form discreet lymph nodes. The function of the lymph node is to evaluate and, when possible, process and initiate the immune response to the presented antigens. Lymph nodes are like a mesh of reticular cells containing lobules wherein the antigens are presented to the immune system. Lobules anatomically contain 3 discreet compartments (cortex, paracortex, and medulla) in which B-cells, T-cells, and macrophages are separately sequestered. The appropriate cell line responds to the presented antigen by increasing its numbers. Cell lines can commonly multiply by 3 to 5 times in 6 to 24 hours. The reticular network can stretch to contain the cell-swollen lobules. This increases the size of the lymph node and causes the clinical phenomenon of lymphadenopathy. Lymph nodules are integrated with afferent and efferent blood vessels, allowing a rich interface between intravascular and extravascular spaces. Macroscopically, the result is antigenic "policing" of intravascular and interstitial fluids and a ready immune response to threats. Microscopically, the decentralized antigen presentation and response hubs allow for prompt action with an economy of lymphoid resources.[23]

History and Physical

A history and physical examinations are the cornerstones of time- and cost-effective diagnosis of adenopathy. The depth and extent of the H&P conducted are proportional to the obscurity of the etiology of the adenopathy. The obvious presence of strep pharyngitis and its related localized anterior cervical adenopathy requires far less clinical brainpower than generalized adenopathy secondary to sarcoidosis or Gaucher disease.

The history involves gathering 5 important components: chronicity, localization, concomitant symptoms, patient epidemiology, and pharmacological exposure.

- Chronicity: The accepted definition of "chronic adenopathy" is a duration of greater than 3 weeks. The observation that a duration of fewer than 2 weeks or greater than 1 year is usually associated with benign causality.

- Localization: The first determination is if the adenopathy can be viewed as localized or generalized. The accepted definition of generalized lymphadenopathy is clinical lymphadenopathy in 2 or more non-contiguous areas. Generalized adenopathy may indicate systemic illness, and the workup is typically more laboratory and imaging-intensive and pursued more rapidly. Localized beds of enlarged nodes reflect possible localized pathology in the areas in which they drain.

- Physical characterization of the node itself

- Concomitant symptoms: The presence or absence of constitutional symptoms is a major cue in determining the pace and depth of the workup in lymphadenopathy when taken in the clinical context. For example, fever, chills, night sweats, weight loss, and fatigue are worrisome in the setting of generalized lymphadenopathy. However, similar symptoms are acceptable in localized cervical lymphadenopathy and a concomitant Flu or Strep.

- Epidemiology: The epidemiological search for lymphadenopathy includes questions about diet, pet exposure, insect bite, recent blood exposure, high-risk sexual behavior or intravenous drug use, occupational exposure to animals, and travel-related epidemiology, especially attention to travel to the Third World or the Southwest in the United States.

- Pharmacological exposure: A thorough medical history is necessary, including prescription medications, over-the-counter medications, supplements, and herbal medicines.[7][24]

The physical examination can be quite revealing, especially with the location of the adenopathy and consideration of the lymphatic drainage of the related areas. Once the determination has been made that the lymphadenopathy is either localized or general, strict attention must be paid to the localized area. For example:

- Submandibular nodes typically drain the tongue, the lips, the mouth, and the conjunctiva

- Submental nodes typically drain the lower lip portions of the oropharynx and the cheek

- Jugular lymphadenopathy typically drains the tongue, the tonsils, the pinna, and the parotid gland

- Posterior cervical adenopathy is typically indicative of the scalp, neck, skin of the arms, and legs

- Pectoral thoracic cervical and axillary drainage

- Suboccipital nodes reflect drainage of the scalp in the head, and preauricular nodes reflect eyelids, conjunctiva temporal region, and pinna drainage.

- Postauricular nodes reflect drainage at the scalp in the external auditory meatus.

- The right supraclavicular node represents drainage of the mediastinum of the lungs in the esophagus.

- Axillary nodes typically create the arm at the thoracic wall and the breast.

- The epitrochlear nerve roots typically drain the ulnar aspect of the forearm and the hand.

- Inguinal nodes drain the penis, the scrotum, the vulva, the vagina, the perineum, the gluteal region, and the lower abdominal wall and portions of the lower anal canal [25]

Characterization of the node morphology:

- Tenderness or pain may result from an inflammatory process or perforation and also may result from hemorrhage into the necrotic center of a malignant node. (Presence or absence of pain is not a reliable differentiating factor for malignant nodes, though.)

- Consistently firm, rubbery nodes may suggest lymphoma; softer nodes are usually the result of infection or inflammatory conditions; hard, stonelike nodes are typically a sign of cancer more commonly metastatic than primary.

- "Shotty" nodes are small, scattered nodes that feel like shotgun pellets under the skin. This configuration is typically found in the cervical nodes of children with viral illnesses.

- The designation of a "matting" configuration of nodes describes the pattern of clustered, seemingly conjoined lymph nodes. This is indicative of, but not pathognomonic, malignancy.[26]

Evaluation

Laboratory Evaluation of Lymphadenopathy

- CBC with manual differential: A foundational test for diagnosing generalized and regional lymphadenopathy. The number and differential of the white blood cells can indicate bacterial, viral, or fungal pathology. In addition, characteristic white blood cell patterns are observed, with several hematological neoplasms producing lymphadenopathy.

- EBV serology: Epstein-Barr viral mono is present, causing regionalized lymphadenopathy

- Sedimentation rate: A measure of inflammation, though not diagnostic, can contribute to diagnostic reasoning.

- Cytomegalovirus titers: This viral serology is indicative of possible CMV mononucleosis

- HIV serology: This serology can be used to diagnose acute HIV syndrome-related lymphadenopathy or to infer the diagnosis of secondary HIV-elated pathologies causing lymphadenopathy.

- Bartonella henselae serology: Serology that may be indicative of the diagnosis of cat-scratch lymphadenopathy

- FTA\RPR: These tests can establish if syphilis is a cause of lymphadenopathy

- Herpes simplex serology: Serological testing to discern if the herpes-related, mononucleosis-like syndrome is present or if regionalized inguinal adenopathy is secondary to herpes simplex exposure

- Toxoplasmosis serology: These serological tests can lead to a diagnosis of acute toxoplasmosis as a cause of lymphadenopathy

- Hepatitis B serology: Serological tests for hepatitis B to establish it as a contributing factor for lymphadenopathy

- ANA: A serological screening test for systemic lupus erythematosus that can help establish it as a cause for generalized lymphadenopathy

Diagnostic Radiological Testing

- Chest x-ray: This radiological imaging modality can reveal tuberculosis, pulmonary sarcoidosis, and pulmonary neoplasm.

- Chest computed tomography (CAT) scan: This radiological imaging modality can define the above processes and reveal hilar adenopathy (see Image. Bilateral Hilar Adenopathy).

- Abdominal and pelvic CAT scan: These images, in combination with chest CAT scan, can be revealed in cases of supraclavicular adenopathy and the diagnosis of secondary neoplasm.

- Ultrasonography: This imaging modality can assess the number, size, shape, marginal definition, and internal structures in patients with lymphadenopathy. Color Doppler ultrasonography is used to distinguish the vascular pattern between older, preexisting lymphadenopathy and recent (newly active) lymphadenopathy. Studies have indicated that a low long-axis to short-axis ratio of lymphadenopathy as measured by ultrasound can be a significant indicator of lymphoma and metastatic cancer as a cause of lymphadenopathy.

- MRI scanning: As with CAT scanning, this diagnostic imaging modality has great utility in evaluating thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic masses.[27]

PPD

Tuberculosis is among the leading causes of both regional and generalized adenopathy in the non-industrialized world [28]

Treatment / Management

The management and treatment of lymphadenopathy are dependent on its etiology. For example:

- Lymphadenopathy caused by a primary neoplasm: Treatment of the neoplasm

- Lymphadenopathy caused by metastasis-diagnosis of the primary: Treatment of the metastasis and primary

- Lymphadenopathy caused by bacterial disease: Supportive care, antibiotics, and elimination of nidus of infection if applicable

- Lymphadenopathy caused by viral disease: Observation and supportive care or treatment of the virus if particular antiviral medications exist

- Lymphadenopathy caused by a toxin or medication exposure: Removal of offending medication if possible or avoidance of toxin [29]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of the etiology of lymphadenopathy can be thought of in the following algorithm. After a thorough history and physical examination, lymphadenopathy can be initially categorized as:

- Diagnostic-where the practitioner has a proximal cause for the lymph nodes and can treat them. Examples would be strep pharyngitis or localized cellulitis.

- The lymphadenopathy pattern history and physical examination can be suggestive; an example would be mononucleosis. If the practitioner has a strong clinical index of suspicion, he can perform a confirmatory test, which, if positive, he can then proceed to treat the patient.

- Unexplained lymphadenopathy.

- Unexplained lymphadenopathy can be generalized into localized or generalized lymphadenopathy.[7]

Unexplained localized lymphadenopathy (after careful review of the history and epidemiology) is further divided into patterns at no risk for malignancy or severe illness; in this case, the patient can be observed for 3 to 4 weeks, and if response or improvement can be followed. The other alternative is if the patient is found to have a risk for malignancy or serious illness, a biopsy is indicated.[30] Unexplained generalized lymphadenopathy can be approached after a review of epidemiological clues and medications with initial testing with a CBC with manual differential and mononucleosis serology; if either is positive and diagnostic, proceed to treatment. If both are negative, the second workup approach would be a PPD, an RPR, a chest x-ray, ANA, hepatitis BS antigen serology, and HIV. Additional testing modalities and lab tests may be indicated depending on clinical cues. If the results of this testing are conclusive, the practitioner can proceed to diagnosis and treatment of the illness. If the testing results are still unclear, proceed to a biopsy of the most abnormal of the nodes. The most functional way to investigate the differential diagnosis of lymphadenopathy is to characterize it by node pattern and location, obtain pertinent history, including careful evaluation of epidemiology, and place the patient in the appropriate arm of the algorithm to evaluate lymphadenopathy.

Generalized Lymphadenopathy

Common Infective Causation

- Mononucleosis

- HIV

- Tuberculosis

- Typhoid fever

- Syphilis

- Plague [31] See Image. Lymphadenopathy Infective Causation, Plague.

Malignancies

- Acute leukemia

- Hodgkin lymphoma

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma [32]

Metabolic Storage Disorders

- Gaucher disease

- Niemann-Pick disease [33]

Medication Reactions

- Allopurinol

- Atenolol

- Captopril

- Carbamazepine

- Cephalosporin(s)

- Gold

- Hydralazine

- Penicillin

- Phenytoin

- Primidone

- Pyrimethamine

- Quinidine

- Sulfonamides

- Sulindac [34]

Autoimmune Disease

- Sjogren syndrome

- Sarcoidosis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Systemic lupus erythematosus [35]

Localized Peripheral Lymphadenopathy

Head and Neck Lymph Nodes

Viral infection

- Viral URI

- Mononucleosis

- Herpes virus

- Coxsackievirus

- Cytomegalovirus

- HIV [36]

Bacterial infection

- Staphylococcal aureus

- Group A Streptococcus pyogenes

- Mycobacterium

- Dental abscess

- Cat scratch disease [37]

Malignancy

- Hodgkin disease

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- Thyroid cancer

- Squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck [38]

Inguinal Peripheral Lymphadenopathy

Infection

- STDs

- Cellulitis [39]

Malignancy

- Lymphoma

- Squamous cell carcinoma of genitalia

- Malignant melanoma [40]

Axillary Lymphadenopathy

Infection

- Localized Staphylococcal aureus

- Cat-scratch disease

- Brucellosis [41]

Malignancy

- Lymphoma

- Breast cancer

- Melanoma [42]

Reaction to breast implants [43]

Supraclavicular Adenopathy

Infections

- Mycobacteria

- Fungi

Prognosis

Whether localized or generalized, the prognosis of lymphadenopathy depends entirely on the etiology of the enlarged lymph nodes. A treatable bacterial or viral illness causes most adenopathy in the general medicine office. However, HIV, active tuberculosis, and neoplasm all have more guarded prognoses. Generalities include the majority of localized lymphadenopathy, which has a better prognosis than the majority of generalized lymphadenopathy secondary to etiologies. Etiologies established earlier in a clinical setting tend to have better prognoses than those established later.[44]

Complications

Pitfalls and pearls of the diagnosis and treatment of lymphadenopathy include:

- There is no substitute for a thorough history and careful physical examination in the workup of lymphadenopathy.

- Most localized and generalized lymphadenopathy have a relatively benign treatable cause.

- All generalized lymphadenopathy merits careful evaluation and workup.

- The gold standard for diagnosis of lymphadenopathy remains tissue diagnosis of the node by incisional biopsy.

- A careful review of the patient's epidemiological and personal medical history provides daily clues as to when lymphadenopathy can be safely observed for change or resolution over 2 to 4 weeks.

- Supraclavicular lymphadenopathy is almost universally indicative of underlying thoracic or abdominal malignancy.[45]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education plays a significant role in deterring the processes that can cause pathological lymphadenopathy. Important topics to discuss include:

- Smoking cessation, alcohol moderation, modification of unsafe sexual practices, and avoidance of drug use can significantly decrease the rate of cancers, HIV, hepatitis B and C, and sexually transmitted infections.

- Appropriate vaccination, good hygiene, good public sanitation, and careful infectious disease protocols can significantly decrease the recurrence rate and transmission of infections causing lymphadenopathy.

Pearls and Other Issues

Key facts to keep in mind about adenopathy are as follows:

- Seventy-five percent of all lymphadenopathies are localized, with more than 50% seen in the head and neck area.

- Most supraclavicular lymphadenopathies are associated with malignancy.

- A careful history and physical examination is the most powerful tool in diagnosing lymphadenopathy.

- The gold standard for diagnosis of lymphadenopathy is tissue obtained either by fine-needle aspiration or excisional biopsy.

- All generalized lymphadenopathy needs to be carefully worked up, and the diagnosis must be established.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

After a careful workup, the primary provider can diagnose many of the causes of lymphadenopathy. However, when the diagnosis in question varies, consultants can be utilized to clarify the situation to provide the best outcomes. Consultations that are typically requested for patients with adenopathy include the following:

Interventional radiology: Examining the tissue specimen remains the gold standard for diagnosing lymphadenopathy.

General surgery, otorhinolaryngology, urological, thoracic surgery: Clinical circumstances may dictate the need for an excisional biopsy as opposed to a biopsy sample examination

Infectious disease: For the provision of input on both diagnosis and treatment of infectious causes of lymphadenopathy

Rheumatology: For the provision of input on both diagnosis and treatment of rheumatologic diseases causing lymphadenopathy

Allergy and immunology: For the provision of input on both diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune, toxicological exposure, and medication-related exposure causes of lymphadenopathy

Hematology and oncology: For the provision of input on both diagnosis and treatment of neoplastic causes of lymphadenopathy

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Lymphadenopathy Infective Causation, Plague. This patient with plague displays a swollen, ruptured inguinal lymph node or buboe. After the incubation period of 2 to 6 days, symptoms of the plague appear, including severe malaise, headache, shaking chills, fever, pain, and swelling, or adenopathy, in the affected regional lymph nodes, also known as buboes.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

References

Pannu AK, Prakash G, Jandial A, Kopp CR, Kumari S. Epitrochlear lymphadenopathy. The Korean journal of internal medicine. 2019 Nov:34(6):1396. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2018.218. Epub 2018 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 30514055]

Brucoli M, Borello G, Boffano P, Benech A. Tuberculous neck lymphadenopathy: A diagnostic challenge. Journal of stomatology, oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2019 Jun:120(3):267-269. doi: 10.1016/j.jormas.2018.11.012. Epub 2018 Dec 1 [PubMed PMID: 30513392]

Fajgenbaum DC. Novel insights and therapeutic approaches in idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease. Blood. 2018 Nov 29:132(22):2323-2330. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-05-848671. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30487129]

Dorfman T, Neymark M, Begal J, Kluger Y. Surgical Biopsy of Pathologically Enlarged Lymph Nodes: A Reappraisal. The Israel Medical Association journal : IMAJ. 2018 Nov:20(11):674-678 [PubMed PMID: 30430795]

Kumar S, Gupta P, Sharma V, Mandavdhare H, Bhatia A, Sinha S, Dhaka N, Srinivasan R, Dutta U, Kocchar R. Role of Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Aspiration Cytology of Omentum in Diagnosis of Abdominal Tuberculosis. Surgical infections. 2019 Jan:20(1):91-94. doi: 10.1089/sur.2018.165. Epub 2018 Nov 27 [PubMed PMID: 30481127]

Godfrey J, Leukam MJ, Smith SM. An update in treating transformed lymphoma. Best practice & research. Clinical haematology. 2018 Sep:31(3):251-261. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2018.07.008. Epub 2018 Jul 25 [PubMed PMID: 30213394]

Gaddey HL, Riegel AM. Unexplained Lymphadenopathy: Evaluation and Differential Diagnosis. American family physician. 2016 Dec 1:94(11):896-903 [PubMed PMID: 27929264]

Vukovic S, Anagnostopoulos A, Zbinden R, Schönenberger L, Guillod C, French LE, Navarini A, Roider E. [Painful lymphadenopathy after an insect bite-a case report]. Der Hautarzt; Zeitschrift fur Dermatologie, Venerologie, und verwandte Gebiete. 2019 Jan:70(1):47-50. doi: 10.1007/s00105-018-4237-z. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30229279]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGlushko T, He L, McNamee W, Babu AS, Simpson SA. HIV Lymphadenopathy: Differential Diagnosis and Important Imaging Features. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2021 Feb:216(2):526-533. doi: 10.2214/AJR.19.22334. Epub 2020 Dec 16 [PubMed PMID: 33325733]

Mehrian P, Doroudinia A, Shams M, Alizadeh N. Distribution and Characteristics of Intrathoracic Lymphadenopathy in TB/HIV Co-Infection. Infectious disorders drug targets. 2019:19(4):414-420. doi: 10.2174/1871526518666181016111142. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30324894]

Dunmire SK, Verghese PS, Balfour HH Jr. Primary Epstein-Barr virus infection. Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 2018 May:102():84-92. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2018.03.001. Epub 2018 Mar 5 [PubMed PMID: 29525635]

Patel S, Patel P, Jiyani R, Ghosh S, Patel D. A Rare Case of Hepatic Sarcoidosis Caused By Hepatitis B Virus and Treatment-Induced Opportunistic Infection. Cureus. 2020 Sep 14:12(9):e10454. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10454. Epub 2020 Sep 14 [PubMed PMID: 33072462]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceXochelli A, Oscier D, Stamatopoulos K. Clonal B-cell lymphocytosis of marginal zone origin. Best practice & research. Clinical haematology. 2017 Mar-Jun:30(1-2):77-83. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2016.08.028. Epub 2016 Nov 4 [PubMed PMID: 28288720]

Zhu M, Deng G, Tan P, Xing C, Guan C, Jiang C, Zhang Y, Ning B, Li C, Yin B, Chen K, Zhao Y, Wang HY, Levine B, Nie G, Wang RF. Beclin 2 negatively regulates innate immune signaling and tumor development. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2020 Oct 1:130(10):5349-5369. doi: 10.1172/JCI133283. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32865519]

Angelakis E, Raoult D. Pathogenicity and treatment of Bartonella infections. International journal of antimicrobial agents. 2014 Jul:44(1):16-25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.04.006. Epub 2014 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 24933445]

Improta L, Tzanis D, Bouhadiba T, Abdelhafidh K, Bonvalot S. Overview of primary adult retroperitoneal tumours. European journal of surgical oncology : the journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology. 2020 Sep:46(9):1573-1579. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2020.04.054. Epub 2020 May 21 [PubMed PMID: 32600897]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJakhar D, Singal A, Sharma S, Kotru M. Norfloxacin-Induced Linear IgA Dermatosis. Skinmed. 2020:18(6):374-377 [PubMed PMID: 33397569]

Foissac M, Socolovschi C, Raoult D. [Update on SENLAT syndrome: scalp eschar and neck lymph adenopathy after a tick bite]. Annales de dermatologie et de venereologie. 2013 Oct:140(10):598-609. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2013.07.014. Epub 2013 Aug 23 [PubMed PMID: 24090889]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSiddiqui S, Osher J. Assessment of Neck Lumps in Relation to Dentistry. Primary dental journal. 2017 Aug 31:6(3):44-50. doi: 10.1308/205016817821931079. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30188316]

Loizos A, Soteriades ES, Pieridou D, Koliou MG. Lymphadenitis by non-tuberculous mycobacteria in children. Pediatrics international : official journal of the Japan Pediatric Society. 2018 Dec:60(12):1062-1067. doi: 10.1111/ped.13708. Epub 2018 Dec 10 [PubMed PMID: 30290041]

Prudent E, La Scola B, Drancourt M, Angelakis E, Raoult D. Molecular strategy for the diagnosis of infectious lymphadenitis. European journal of clinical microbiology & infectious diseases : official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology. 2018 Jun:37(6):1179-1186. doi: 10.1007/s10096-018-3238-2. Epub 2018 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 29594802]

Portillo A, Santibáñez S, García-Álvarez L, Palomar AM, Oteo JA. Rickettsioses in Europe. Microbes and infection. 2015 Nov-Dec:17(11-12):834-8. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2015.09.009. Epub 2015 Sep 16 [PubMed PMID: 26384814]

Tsimis ME, Sheffield JS. Update on syphilis and pregnancy. Birth defects research. 2017 Mar 15:109(5):347-352. doi: 10.1002/bdra.23562. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28398683]

Rigilano J. Lymphadenopathy in Children and Young Adults May Be Due to a Periodic Fever Syndrome. American family physician. 2018 Jun 1:97(11):702-703 [PubMed PMID: 30215943]

Weinstock MS, Patel NA, Smith LP. Pediatric Cervical Lymphadenopathy. Pediatrics in review. 2018 Sep:39(9):433-443. doi: 10.1542/pir.2017-0249. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30171054]

Perry AM, Choi SM. Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease: A Review. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2018 Nov:142(11):1341-1346. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2018-0219-RA. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30407860]

Kim JY, Lee H, Yun B. Ultrasonographic findings of Kikuchi cervical lymphadenopathy in children. Ultrasonography (Seoul, Korea). 2017 Jan:36(1):66-70. doi: 10.14366/usg.16047. Epub 2016 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 27998053]

Singh UB, Verma Y, Jain R, Mukherjee A, Gautam H, Lodha R, Kabra SK. Childhood Intra-Thoracic Tuberculosis Clinical Presentation Determines Yield of Laboratory Diagnostic Assays. Frontiers in pediatrics. 2021:9():667726. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.667726. Epub 2021 Aug 25 [PubMed PMID: 34513756]

Edmonds CE, Zuckerman SP, Conant EF. Management of Unilateral Axillary Lymphadenopathy Detected on Breast MRI in the Era of COVID-19 Vaccination. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2021 Oct:217(4):831-834. doi: 10.2214/AJR.21.25604. Epub 2021 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 33543649]

Ge YL, Zhang Q, Wang MH, Zhang HL, Rana MA, Li WQ, Chen Y, Liu CH, Zhang S, Hao C, Zhang C, Zhu XY, Li LQ, Fu AS. Fever with Positive EBV IgM Antibody Combined Multiple Subcutaneous Nodules on Lower Extremities and Cervical Lymphadenopathy Masquerading as Infectious Mononucleosis Proven as Subcutaneous Panniculitis-like T-cell Lymphoma by Subcutaneous Nodule Biopsy Consultation: a Case Report and Literature Review. Clinical laboratory. 2019 Jul 1:65(7):. doi: 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2019.181255. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31307165]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSève P, Pacheco Y, Durupt F, Jamilloux Y, Gerfaud-Valentin M, Isaac S, Boussel L, Calender A, Androdias G, Valeyre D, El Jammal T. Sarcoidosis: A Clinical Overview from Symptoms to Diagnosis. Cells. 2021 Mar 31:10(4):. doi: 10.3390/cells10040766. Epub 2021 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 33807303]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKing RL, Gupta A, Kurtin PJ, Ding W, Call TG, Rabe KG, Kenderian SS, Leis JF, Wang Y, Schwager SM, Slager SL, Kay NE, Koehler A, Ansell SM, Inwards DJ, Habermann TM, Shi M, Hanson CA, Howard MT, Parikh SA. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) with Reed-Sternberg-like cells vs Classic Hodgkin lymphoma transformation of CLL: does this distinction matter? Blood cancer journal. 2022 Jan 28:12(1):18. doi: 10.1038/s41408-022-00616-6. Epub 2022 Jan 28 [PubMed PMID: 35091549]

Ahuja J, Kanne JP, Meyer CA, Pipavath SN, Schmidt RA, Swanson JO, Godwin JD. Histiocytic disorders of the chest: imaging findings. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2015 Mar-Apr:35(2):357-70. doi: 10.1148/rg.352140197. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25763722]

James J, Sammour YM, Virata AR, Nordin TA, Dumic I. Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS) Syndrome Secondary to Furosemide: Case Report and Review of Literature. The American journal of case reports. 2018 Feb 14:19():163-170 [PubMed PMID: 29440628]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMull ES, Aranez V, Pierce D, Rothman I, Abdul-Aziz R. Newly Diagnosed Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Atypical Presentation With Focal Seizures and Long-standing Lymphadenopathy. Journal of clinical rheumatology : practical reports on rheumatic & musculoskeletal diseases. 2019 Oct:25(7):e109-e113. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000681. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29280817]

Fugl A, Andersen CL. Epstein-Barr virus and its association with disease - a review of relevance to general practice. BMC family practice. 2019 May 14:20(1):62. doi: 10.1186/s12875-019-0954-3. Epub 2019 May 14 [PubMed PMID: 31088382]

Maria HKS, Gazzoli E, Drummond MR, Almeida AR, Santos LSD, Pereira RM, Tresoldi AT, Velho PENF. Two-year history of lymphadenopathy and fever caused by Bartonella henselae in a child. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de Sao Paulo. 2022:64():e15. doi: 10.1590/S1678-9946202264015. Epub 2022 Feb 16 [PubMed PMID: 35195167]

Vergeldt TFM, Driessen RJB, Bulten J, Nijhuis THJ, de Hullu JA. Vulvar cancer in hidradenitis suppurativa. Gynecologic oncology reports. 2022 Feb:39():100929. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2022.100929. Epub 2022 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 35106355]

Ferzacca E, Barbieri A, Barakat L, Olave MC, Dunne D. Lower Gastrointestinal Syphilis: Case Series and Literature Review. Open forum infectious diseases. 2021 Jun:8(6):ofab157. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab157. Epub 2021 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 34631920]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKubo T, Hino A, Fukushima K, Shimomura Y, Kurashige M, Kusakabe S, Nagate Y, Fujita J, Yokota T, Kato H, Shibayama H, Tanemura A, Hosen N. Nivolumab-induced systemic lymphadenopathy occurring during treatment of malignant melanoma: a case report. International journal of hematology. 2022 Aug:116(2):302-306. doi: 10.1007/s12185-022-03312-0. Epub 2022 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 35201591]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMa L, Ma J, Chen X, Dong L. A 10-year retrospective comparative analysis of the clinical features of brucellosis in children and adults. Journal of infection in developing countries. 2021 Aug 31:15(8):1147-1154. doi: 10.3855/jidc.13962. Epub 2021 Aug 31 [PubMed PMID: 34516423]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWang X, Luo Y, Liu L, Wei J, Lei H, Shi S, Yang L. Metastatic adenocarcinoma to the breast from the lung simulates primary breast carcinoma-a clinicopathologic study. Translational cancer research. 2021 Mar:10(3):1399-1409. doi: 10.21037/tcr-20-2250. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35116465]

Theodosiou AA, Houghton R, Shepherd N, Lillie P. Painful lymphadenopathy due to silicone breast implant rupture following extensive global air travel. Acute medicine. 2017:16(4):192-195 [PubMed PMID: 29300798]

Manvi S, Mahajan VK, Mehta KS, Chauhan PS, Vashist S, Singh R, Kumar P. The Clinical Characteristics, Putative Drugs, and Optimal Management of 62 Patients With Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and/or Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: A Retrospective Observational Study. Indian dermatology online journal. 2022 Jan-Feb:13(1):23-31. doi: 10.4103/idoj.idoj_530_21. Epub 2022 Jan 24 [PubMed PMID: 35198464]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAbidoye O, Raybon-Rojas E, Ogbuagu H. A Rare Case of Epstein-Barr Virus: Infectious Mononucleosis Complicated by Guillain-Barré Syndrome. Cureus. 2022 Jan:14(1):e21085. doi: 10.7759/cureus.21085. Epub 2022 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 35165547]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence