Introduction

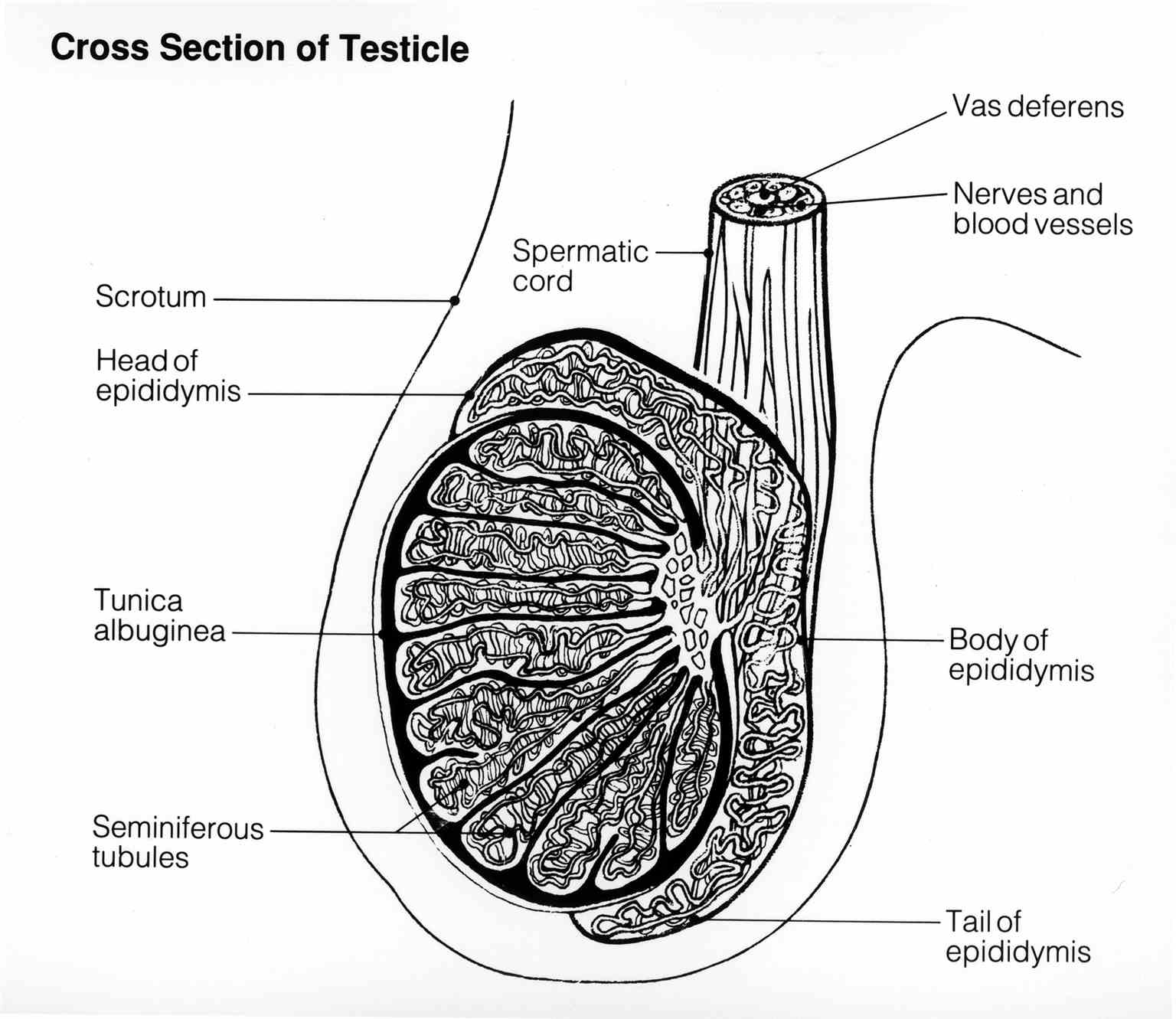

The testes are male sex glands that have both an endocrine and exocrine function. The testes are oval-shaped reproductive structures that are found in the scrotum and separated by the scrotal septum. The shape of the testes is bean-shaped and measures three cm by five cm in length and 2 cm to 3 cm in width. When palpated through the scrotum, the testes are smooth and soft. The spermatic cord suspends the superior aspect of the testes. At the inferior end, the testes are attached to the scrotum by the scrotal ligament which is a remnant of the gubernaculum. In general, the left testis is affixed slightly lower than the right testis.[1][2]

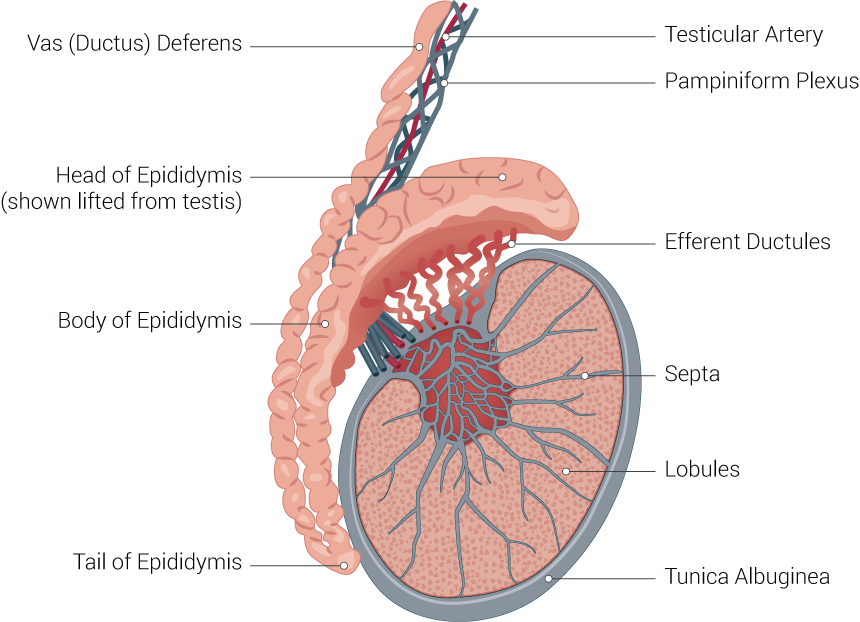

The double-layered tunica vaginalis envelop the testes except at the posterior and superior borders where the epididymis and spermatic cord are attached. The visceral or inner layer of the tunica vaginalis is close to the epididymis, testes and vas deferens. On the posterior lateral surface of the testes, there is a small space between the testes and body of the epididymis which is known as the sinus of the epididymis. Deep to the tunica vaginalis is located the tunica albuginea, which is a durable fibrous covering of the testes.

The epididymis is a small curved shaped elongated structure which is highly convoluted and tightly compressed. When open in a straight line, it is estimated that its length is about 20 feet. The epididymis is found on the posterior border of the testis and consists of three parts which include the head (caput), body (corpora), and tail (Cauda). The head of the epididymis lies at the upper pole of the testes and receive seminal fluid from the ducts of the testis. It then permits passage of sperm into the distal portion of the epididymis. Because of its length, the epididymal ducts have ample space for storage and maturation of sperm.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The testis is the male reproductive gland that is responsible for producing sperm and making androgens, primarily. Testosterone levels are controlled by the release of Luteinizing Hormone (LH) from the anterior pituitary gland; whereas, Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) levels control sperm production.

Embryology

The testes start as an undifferentiated gonad in the retroperitoneum area. The testis-determining factors (SRY gene) present on the Y chromosome causes the gonad to differentiate into the testes. In females, the SRY gene is absent, and hence the gonad turns into an ovary. As the fetus starts to mature, the testes begin to produce the male sex hormone, testosterone. This sex hormone permits the development of the male genitalia.[3]

The tunica albuginea forms a connective tissue latery between the seminiferous tubules and the rest of the testis through invagination. The Sertoli celss start to make make Mullerian-inhibiting Substance (MIS) which causes regressioin of the Mullerian ducts at 8 to 10 weeks. The only remaining remnants of the Mullerian ducts in an adult male are the appendix testis and the prostatic utricle.

During the third trimester of pregnancy, the testes, which are located in the abdomen, starts their descent into the inguinal canal and then to its final destination in the scrotum. During this journey, they pass through the peritoneum, the abdominal wall, and the inguinal canal. During development the inguinal canal contains the processus vaginalis, which is a structure that develops from the peritoneum. It allows the testes to descend and then eventally undergoes apoptosis and becomes the tunica vaginalis which surrounds part of the testis. Failure of the closure of the processus vaginalis may lead to complications such as communicating hydrocele and inguinal hernia. [4]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The testicular arteries supply blood to the testes. They arise from the anterolateral segment of the abdominal aorta just below the origin of the renal arteries. The vessels travel in the retroperitoneum and cross over the ureter, pass through the deep inguinal ring, and join the spermatic cord. Additional blood supply to the testes comes from the artery of the vas deferens and the cremasteric artery.

Venous drainage from the testes is via the pampiniform plexus which lies anterior to the vas deferens. The veins converge superiorly to form the testicular vein. The right testicular vein joins the vena cava, and the left testicular vein drains into the left renal vein. Drainage of the lymphatics from the testes follows the same path as the testicular arteries and drain to the preaortic lymph nodes.[5]

Nerves

The testes have innervations from both sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers.[6]

Muscles

As the testes move from the abdomen into the scrotum, it is gradually enveloped by several layers of muscle tissue, the internal spermatic fascia, the cremasteric muscle and fascia, and the external spermatic fascia. The daily degree of testicular descent varies according primarily to temperature. This is controlled by the cremaster muscles.[7]

Physiologic Variants

Two vestigial embryonic structures with no known physiologic function include the following:

- At the cranial end of the paramesonephric duct (Mullerian duct), sometimes one will find the appendix testis. This pear-shaped vestigial structure is found in about 2% of testes, and it is typically located at the superior pole in the groove between the head of the epididymis and testis.

- Also at the cranial end of the mesonephric duct one will sometimes find the appendix of the epididymis which is found in about 25% of testes. Their location is variable but often project from the head of the epididymis.

- In about 7% of males, the epididymis may be located on the anterior surface of the testis.

Surgical Considerations

Cryptorchidism is an important disorder to recognize early in life not only to preserve sterility but also to reduce the risk of testicular cancer. Unless the surgeon can surgically bring the testes back into the scrotum where it can be under surveillance, the undescended testes should be removed. It is also important to know that there is an increased risk of cancer in the contralateral testes and hence regular self-examinations are highly recommended.[8][9]

Sometimes serous fluid can accumulate in between the layers of the tunica vaginalis leading to a hydrocele. This could be triggered by inflammation, trauma or a congenital cause due to persistent communication with the abdominal cavity.

In young men, testicular torsion is a surgical emergency. The blood supply must be restored within 6 hours of the start of symptoms; the testes need to be fixed in the scrotum to prevent recurrence. Most urologists will also fix the contralateral testes at the same time.

The descent of the testes may be delayed or arrested along the course in the inguinal canal and may be complicated by an inguinal hernia. All true undescended testes will have associated inguinal hernias. This is not true for retractile testicles.

Clinical Significance

Cryptorchidism (non-descent of the testis) not only leads to infertility but carries a risk of testicular cancer. If the abnormal testis is not removed, close surveillance is necessary. The primary treatment for cryptorchidism is repositioning of the cryptorchid testes which is called orchidopexy. It should be performed before 1 year of birth in those with congenital cryptorchidism in order to best prevent cancer.[10]

Sometimes a hydrocele (serous fluid) can result when fluid collects between the layers of the tunica vaginalis. A hydrocele may be due to an infection, trauma, or congenital factors. One common congenital factor is through incomplete closure of the processus vaginalis. [4]

Other Issues

In premature infants, the descent of the testes is often not complete. Thus, after birth attention should be paid to the undescended testes. In some cases, the testes may exit the superficial inguinal ring but may then pass between the thigh and scrotum to rest in the perineum- resulting in an ectopic testis.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Tsili AC, Sofikitis N, Stiliara E, Argyropoulou MI. MRI of testicular malignancies. Abdominal radiology (New York). 2019 Mar:44(3):1070-1082. doi: 10.1007/s00261-018-1816-5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30386879]

Yang Y, Workman S, Wilson M. The molecular pathways underlying early gonadal development. Journal of molecular endocrinology. 2018 Jul 24:():. pii: JME-17-0314. doi: 10.1530/JME-17-0314. Epub 2018 Jul 24 [PubMed PMID: 30042122]

Favorito LA, Sampaio FJ. Testicular migration chronology: do the right and the left testes migrate at the same time? Analysis of 164 human fetuses. BJU international. 2014 Apr:113(4):650-3. doi: 10.1111/bju.12574. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24238431]

Dagur G, Gandhi J, Suh Y, Weissbart S, Sheynkin YR, Smith NL, Joshi G, Khan SA. Classifying Hydroceles of the Pelvis and Groin: An Overview of Etiology, Secondary Complications, Evaluation, and Management. Current urology. 2017 Apr:10(1):1-14. doi: 10.1159/000447145. Epub 2017 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 28559772]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKotian SR, Pandey AK, Padmashali S, Jaison J, Kalthur SG. A cadaveric study of the testicular artery and its clinical significance. Jornal vascular brasileiro. 2016 Oct-Dec:15(4):280-286. doi: 10.1590/1677-5449.007516. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29930605]

Svingen T, Koopman P. Building the mammalian testis: origins, differentiation, and assembly of the component cell populations. Genes & development. 2013 Nov 15:27(22):2409-26. doi: 10.1101/gad.228080.113. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24240231]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKayalioglu G, Altay B, Uyaroglu FG, Bademkiran F, Uludag B, Ertekin C. Morphology and innervation of the human cremaster muscle in relation to its function. Anatomical record (Hoboken, N.J. : 2007). 2008 Jul:291(7):790-6. doi: 10.1002/ar.20711. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18449892]

Cheng L, Albers P, Berney DM, Feldman DR, Daugaard G, Gilligan T, Looijenga LHJ. Testicular cancer. Nature reviews. Disease primers. 2018 Oct 5:4(1):29. doi: 10.1038/s41572-018-0029-0. Epub 2018 Oct 5 [PubMed PMID: 30291251]

Shpunt I, Leibovici D, Ikher S, Kovalyonok A, Avda Y, Jaber M, Bercovich A, Lindner U. Spermatogenesis in Testicles with Germ Cell Tumors. The Israel Medical Association journal : IMAJ. 2018 Oct:20(10):642-644 [PubMed PMID: 30324783]

Gurney JK, McGlynn KA, Stanley J, Merriman T, Signal V, Shaw C, Edwards R, Richiardi L, Hutson J, Sarfati D. Risk factors for cryptorchidism. Nature reviews. Urology. 2017 Sep:14(9):534-548. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2017.90. Epub 2017 Jun 27 [PubMed PMID: 28654092]