Introduction

Human leukocyte antigens (HLA) are genes in major histocompatibility complexes (MHC) that help code for proteins that differentiate between self and non-self. They play a significant role in disease and immune defense. They are beneficial to the immune system but can also have detrimental effects. Some of the immune system effects are the interaction with complement, the cytotoxic effect of T cells, and cellular humoral immunity. Additionally, they play a role in autoimmunity and continue to be the target of researchers for their further effects and interactions.[1]

Fundamentals

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Fundamentals

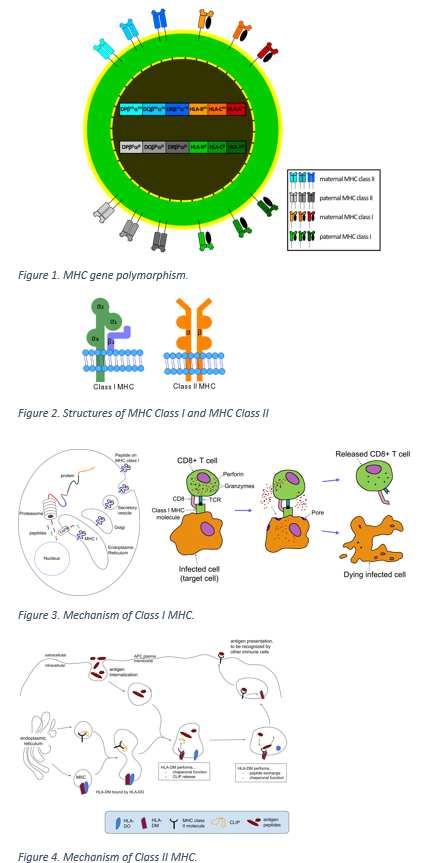

Human leukocyte antigens are of three main types. Class I HLA antigens include HLA-A, B, and C molecules; class II, which includes HLA-DR, -DQ, and -DP loci, are on antigen-presenting cells; and class III contains genes for proteins that have immune functionality.[1]

Issues of Concern

HLA antigen sensitization can become a problem for patients undergoing procedures such as stem cell transplants. HLA antigens have a significant role in transplant-mediated rejection, which falls under the following two categories:

T-cell-mediated Rejection

In T-cell-mediated rejection, the T-cell becomes activated because of the interaction between the T-cell receptor and the HLA-peptide combination from the donor.

Antibody-mediated Rejection

In antibody-mediated rejection, the T-helper cells are co-stimulated, and there is a concurrent inflammatory response, leading to the recognition of foreign HLA molecules.

Due to the possibility of these two types of rejection, laboratories measure the HLA antibodies in circulation to determine the risk of rejection.[1]

HLA types also had correlations with an increased risk of particular diseases. For example, early-onset myasthenia gravis correlates with HLA-B8 as the unique genetic factor that leads to the onset of the disease.[2] Although of unknown etiology, multiple sclerosis has been shown to have a high rate of correlation with the HLA-DR2 antigen.[3] Additionally, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) has been shown to precipitate complex biological interactions in the body. Some of these interactions include HLA-DR4, a glycopeptide from type II collagen, and a T-cell receptor, shown to be correlated with the development of RA.[4]

Cellular Level

The HLA class I is present on all nucleated cell surfaces and presents intracellular peptides to cytotoxic T-cells in the immune system.[4]

HLA plays a role in cellular immunity, particularly noted in transplant reactions. Particular antibodies, such as anti-HLA-B and anti-HLA-DQ, can bind complement.[5]

Molecular Level

HLA antigens can be variable, and researchers have investigated their presence and function to determine their use in disease diagnosis and treatment. HLA polymorphisms can change depending on the epidemiological composition of a particular population, so this presents an important area of research to further delve into as technology progresses. Studies can be performed on specific demographics of humans to find out more about the presence of particular diseases that have a predilection in certain groups. For example, in 2018, a trial was conducted in Thailand to evaluate the efficacy of a Dengue vaccine. The HLA antigens were mapped in the population, and researchers identified 201 different HLA antigens through next-generation sequencing techniques. Through this investigation, researchers identified HLA alleles with higher frequencies in the population and could incorporate that information and begin applying it to disease association in the population.[6]

Function

HLA antigens, particularly the A, B, and C loci, are highly variable, especially in the extracellular domains, as evidenced by the over 300 class I alleles that researchers have identified.[5] The parts of the HLA antigens that are the most variable reside near the peptide-binding groove. The variability alters the interactions with T-cell receptors and the peptide-binding specificity; this changes the function of the HLA antigens, which can alter the immune response and disease resistance.[4]

In addition to their variability and function as peptide receptors, they act at different sites with beta-2-microglobulin, an alpha-beta T-cell receptor, and inhibitory molecules.[7] The various alleles within each class of HLA antigens allow for these additional functions.

Testing

Types of tests include cellular assays, immunologic, and molecular tests.

Conventionally, HLA classes are detected by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). PCR uses variable exon sequences that encode the first amino-terminal from the HLA domains. From there, the HLA sequences from the database are used in hybridization with the amplified PCR products.[8]

There have also been recent developments in less expensive assays to detect specific HLA antigens, such as high-resolution melting assays.[9]

The standard technique for identifying HLA class I and class II antigens has been the complement-mediated microlymphocytotoxicity technique. In this technique, HLA sera are obtained from alloimmunized women, and those specificities get determined by matching against a panel with already known HLA types.[8]

Testing for HLA antigens often is by bead-based multiplexed immunoassay system technology. In this test, HLA protein beads coat the surface of microspheres. A fluorescence quantification system measures the level of HLA antibody binding to each of the beads.

Testing in patients with HLA antibodies in their circulation requires a cross-match before transplantation. This traditional cross-match entails patient serum mixed with lymphocytes that have derived from the donor. "Virtual" cross matches may also be done to estimate the transplant risk by measuring the levels of circulating HLA antibody using single antigen beads and bead-based multiplexed immunoassay system technology.[3]

Pathophysiology

Often, the specific pathophysiology for how HLA antigens are associated with a disease is not well known. However, HLA antigens play a role in autoimmunity. For example, in type I diabetes mellitus, the DR3-DQ2 haplotype is seen at an increased percent compared to the general population. The same haplotype is also associated with juvenile autoimmune thyroiditis. Other haplotypes can be protective for diseases, such as DRB1*14:01, which has protective effects against type I diabetes.[10]

Clinical Significance

Graft-versus-host Disease

A major clinical significance of HLA antigens is their role in transplant rejection.

The opposite can occur when immune cells get transplanted with the graft into the recipient. Hematopoietic progenitor cell transplantation (e.g., bone marrow, stem cells) must mainly deal with this phenomenon. Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is caused by the presence of donor antibodies against HLA class II antigens. One study at Henri-Mondor University Hospital in France demonstrated that when donors have antibodies against the specific recipient HLA antigens, there is a correlation with the incidence of GVHD.[3]

A study in the UK of stem cell transplants between 1996 and 2003 showed that patients with a class I HLA mismatch were more likely to developed chronic GVHD. Additionally, the pairs that had the mismatches also had a higher mortality rate after one year. Multiple HLA mismatches show higher rates of GVHD.[11]

HLA antigens can be matched when administering blood products. Research has demonstrated that blood banks that use the HLA genotypes of the blood donors have better transfusion outcomes. There has been a discussion of the possibility of creating a database with genotyped donors to make it slightly easier to find blood for patients with rare HLA antibodies so that their transfusions can have less risk of adverse outcomes because of having matched donors.[12]

As discussed above, studies have identified particular HLA antigens have as correlating with disease processes. These allow for the development of specific treatments for diseases.

Multiple Sclerosis

HLA-DR2 is associated with multiple sclerosis. Since there is such a strong association between the disease and the antigen, there have been studies looking at immunotherapy to target the DR2 antigen in the treatment of the disease. In one particular study, the molecule PV-267 was examined for its promise as a therapy. PV-267 functions as a cytokine inhibitor and inhibits the proliferation of myelin-specific DR2 antigens. By using PV-267 derived from multiple sclerosis patients, researchers found the potential for further therapeutic options.[13]

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis shows strong associations with DR4. These have been thought to indicate disease susceptibility. When DR4 binds with a class II-associated peptide, it may indicate an increased risk for rheumatoid arthritis. The DR4 binding changes the presentation of the citrullinated peptides, contributing to the development of the disease.[14]

Graves Disease

Graves disease is associated with HLA-DR3. In addition to environmental factors, the HLA haplotype plays a significant role in disease development. Important clinically, HLA typing may help to predict the outcome of Graves disease before and post-antithyroid medical therapy.[15] The typing can be used to associate increased and decreased allele values during therapy.[16]

Behçet Disease

Behçet disease is associated with HLA-B51, which influences the clinical features of the disease. Patients with the HLA-B51 haplotype have been shown to develop symptoms of the disease earlier in life (less than 40 years of age). Additionally, neurological and gastrointestinal symptoms of the disease were more prevalent in patients without the HLA-B51 haplotype rather than those who had it.[17]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Carey BS, Poulton KV, Poles A. Factors affecting HLA expression: A review. International journal of immunogenetics. 2019 Oct:46(5):307-320. doi: 10.1111/iji.12443. Epub 2019 Jun 10 [PubMed PMID: 31183978]

Gotfredsen A, Pødenphant J, Nørgaard H, Nilas L, Nielsen VA, Christiansen C. Accuracy of lumbar spine bone mineral content by dual photon absorptiometry. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 1988 Feb:29(2):248-54 [PubMed PMID: 3346735]

Delbos F, Barhoumi W, Cabanne L, Beckerich F, Robin C, Redjoul R, Astati S, Toma A, Pautas C, Ansart-Pirenne H, Cordonnier C, Bierling P, Maury S. Donor Immunization Against Human Leukocyte Class II Antigens is a Risk Factor for Graft-versus-Host Disease. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2016 Feb:22(2):292-299. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.09.027. Epub 2015 Nov 11 [PubMed PMID: 26453972]

Parham P. Function and polymorphism of human leukocyte antigen-A,B,C molecules. The American journal of medicine. 1988 Dec 23:85(6A):2-5 [PubMed PMID: 2462346]

Ayna TK, Koçyİğİt AÖ, Soypaçaci Z, Tuğmen C, Pirim I. Investigation of Anti-HLA Antibodies of Highly Sensitized Patients by Single Antigen Bead and C1q Tests. Transplantation proceedings. 2019 May:51(4):1024-1026. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2019.01.086. Epub 2019 Feb 8 [PubMed PMID: 31101164]

Geretz A, Ehrenberg PK, Bouckenooghe A, Fernández Viña MA, Michael NL, Chansinghakule D, Limkittikul K, Thomas R. Full-length next-generation sequencing of HLA class I and II genes in a cohort from Thailand. Human immunology. 2018 Nov:79(11):773-780. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2018.09.005. Epub 2018 Sep 19 [PubMed PMID: 30243890]

Kostyu DD, Hannick LI, Traweek JL, Ghanayem M, Heilpern D, Dawson DV. HLA class I polymorphism: structure and function and still questions. Human immunology. 1997 Sep 15:57(1):1-18 [PubMed PMID: 9438190]

Smirnova LI. [Climacteric cardioneurosis]. Fel'dsher i akusherka. 1989 Dec:54(12):54-7 [PubMed PMID: 2628004]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceImperiali C, Alía-Ramos P, Padró-Miquel A. Rapid detection of HLA-B*51 by real-time polymerase chain reaction and high-resolution melting analysis. Tissue antigens. 2015 Aug:86(2):139-42. doi: 10.1111/tan.12603. Epub 2015 Jul 14 [PubMed PMID: 26176813]

Fawwad A, Govender D, Ahmedani MY, Basit A, Lane JA, Mack SJ, Atkinson MA, Henry Wasserfall C, Ogle GD, Noble JA. Clinical features, biochemistry and HLA-DRB1 status in youth-onset type 1 diabetes in Pakistan. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 2019 Mar:149():9-17. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2019.01.023. Epub 2019 Jan 30 [PubMed PMID: 30710658]

Shaw BE. The clinical implications of HLA mismatches in unrelated donor haematopoietic cell transplantation. International journal of immunogenetics. 2008 Aug:35(4-5):367-74. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313X.2008.00793.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18976440]

Dutra VF, Bub CB, Costa TH, Santos LD, Bastos EP, Aravechia MG, Kutner JM. Allele and haplotype frequencies of human platelet and leukocyte antigens in platelet donors. Einstein (Sao Paulo, Brazil). 2019 Feb 7:17(1):eAO4477. doi: 10.31744/einstein_journal/2019AO4477. Epub 2019 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 30758400]

Andrews LP, Clark RK, Damjanov I. Mixed glycosidase pretreatment reduces nonspecific binding of antibodies to frozen tissue sections. The journal of histochemistry and cytochemistry : official journal of the Histochemistry Society. 1985 Jul:33(7):695-8 [PubMed PMID: 3891844]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMiyadera H, Tokunaga K. Associations of human leukocyte antigens with autoimmune diseases: challenges in identifying the mechanism. Journal of human genetics. 2015 Nov:60(11):697-702. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2015.100. Epub 2015 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 26290149]

Matsuo T, Ushiroda Y. IDENTICAL TWIN SISTERS WITH CLOSE ONSET OF GRAVES' DISEASE AND WITH MULTIPLE HLA SUSCEPTIBILITY ALLELES FOR GRAVES' DISEASE. Acta endocrinologica (Bucharest, Romania : 2005). 2016 Jan-Mar:12(1):91-95. doi: 10.4183/aeb.2016.91. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31258808]

Vita R, Lapa D, Trimarchi F, Vita G, Fallahi P, Antonelli A, Benvenga S. Certain HLA alleles are associated with stress-triggered Graves' disease and influence its course. Endocrine. 2017 Jan:55(1):93-100. doi: 10.1007/s12020-016-0909-6. Epub 2016 Mar 7 [PubMed PMID: 26951052]

Ryu HJ, Seo MR, Choi HJ, Baek HJ. Clinical phenotypes of Korean patients with Behcet disease according to gender, age at onset, and HLA-B51. The Korean journal of internal medicine. 2018 Sep:33(5):1025-1031. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2016.202. Epub 2017 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 28073242]