Acute ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI)

Acute ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI)

Introduction

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) encompasses conditions characterized by a sudden decrease in myocardial perfusion, presenting as ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), or unstable angina. Globally, over 7 million individuals are diagnosed with ACS annually, with more than 1 million cases requiring hospitalization in the United States each year. STEMI results from the complete blockage of a coronary artery and represents about 30% of all ACS cases. An acute STEMI is marked by transmural myocardial ischemia resulting in myocardial injury or necrosis.[1] The current 2018 clinical definition of myocardial infarction requires confirming the presence of ischemic myocardial injury with abnormal cardiac biomarker levels.[2] STEMI is a clinical syndrome involving myocardial ischemia, electrocardiography (ECG) changes, and chest pain (see Image. Electrocardiogram Tracing for a Case of Proximal Left Anterior Descending Occlusion).

If electrocardiography indicates STEMI, prompt reperfusion through primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) within 120 minutes can lower mortality from 9% to 7% (see Image. ST-segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction on Electrocardiogram).[3] In cases where PCI within this timeframe is not feasible, full-dose fibrinolytic therapy with alteplase, reteplase, or tenecteplase should be administered to patients younger than 75 and without contraindications to medical intervention. Individuals 75 and older should receive half the normal dose of fibrinolytic therapy. Alternatively, full-dose streptokinase may be considered when cost is a concern. Following fibrinolytic treatment, patients should be transferred to a facility capable of performing PCI within the next 24 hours.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

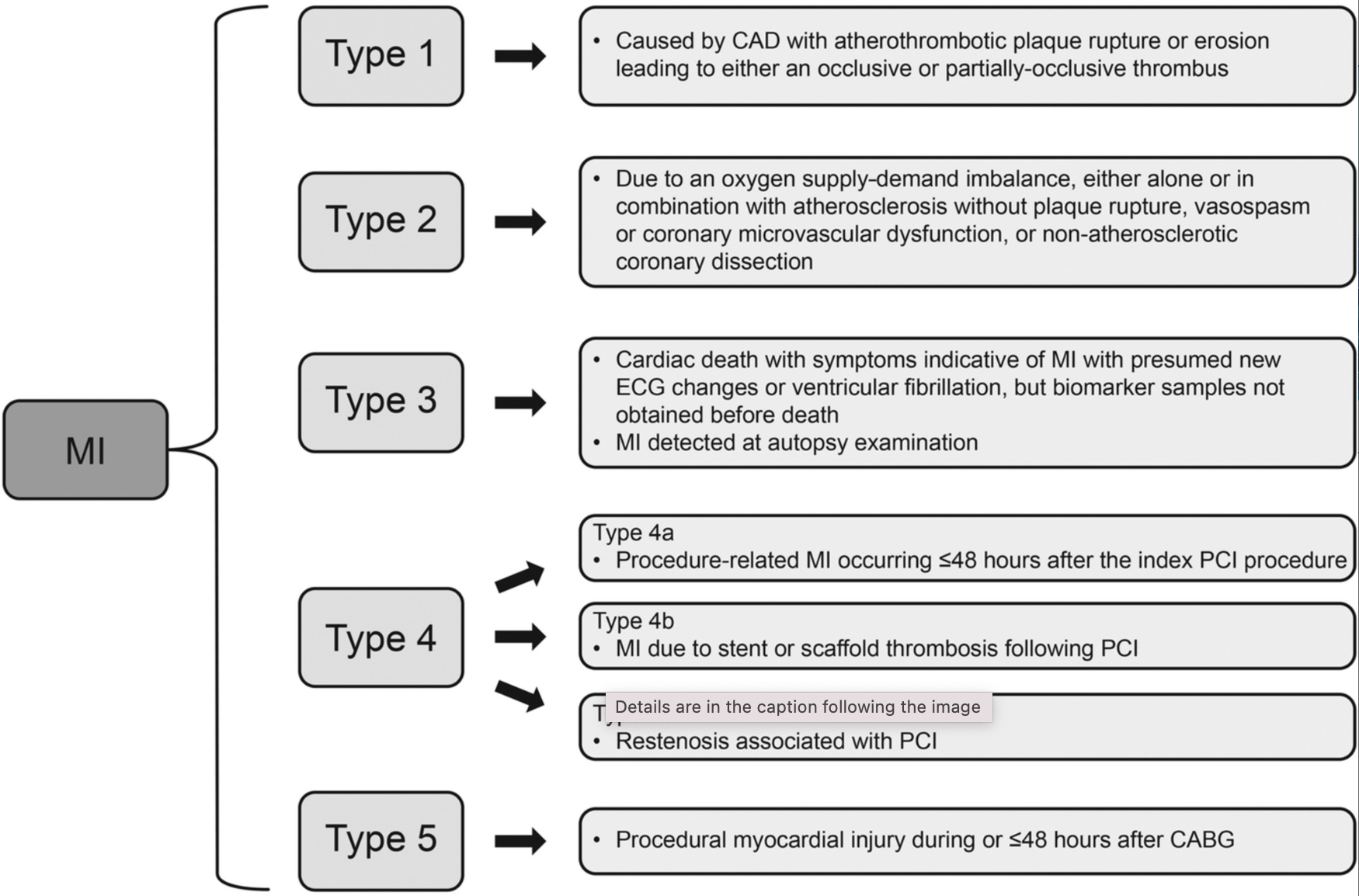

Myocardial infarction, in general, can be classified into types 1 to 5 based on etiology and pathogenesis.[4] Recent advances in cardiovascular imaging, revised ECG criteria, and high-sensitivity cardiovascular biomarker assays have enhanced the ability to classify the different causes of myocardial infarction more precisely. The underlying pathophysiology of type 1 myocardial infarction differs from that of types 2 through 5. Type 1 myocardial infarction is primarily associated with intracoronary atherothrombosis, whereas the other types may result from various mechanisms, some of which may involve an atherosclerotic component. Type 2 myocardial infarction is characterized by an imbalance in myocardial oxygen supply and demand unrelated to acute coronary atherothrombosis. Types 1 and 2 occur spontaneously, while types 4 and 5 are linked to medical procedures. Type 3 is only identified postmortem. Most types 1 and 2 myocardial infarction cases present as NSTEMI, but some manifest as STEMI (see Image. Acute Myocardial Infarction Types).[5]

A STEMI occurs from the occlusion of 1 or more coronary arteries supplying the heart with blood. The cause of this abrupt disruption of blood flow is usually plaque rupture, erosion, fissuring, or dissection of coronary arteries with obstructive thrombus. The major STEMI risk factors are dyslipidemia, diabetes, hypertension, smoking, and a family history of coronary artery disease.[6][7]

Epidemiology

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death and disability worldwide, with low- and middle-resource countries experiencing a disproportionate share of this burden. ACS frequently serves as the initial presentation of CVD. Approximately 5.8 million new cases of ischemic heart disease were reported across the 57 member countries of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) in 2019. The median age-standardized incidence rate was 293.3 per 100,000 people, with an interquartile range of 195.8 to 529.5. CVD continues to be the primary cause of death in ESC countries, contributing to nearly 2.2 million fatalities in women and over 1.9 million deaths in men, according to the latest data. Ischemic heart disease remains the leading cause of CVD mortality, accounting for 38% of deaths in women and 44% in men.[8]

The estimated annual incidence of myocardial infarction in the United States includes 550,000 new cases and 200,000 recurrent cases. In 2013, 116,793 persons in the United States experienced a fatal myocardial infarction, with 57% occurring in men and 43% in women. The average age of incidence of a first myocardial infarction is 65.1 for men and 72 for women. Approximately 38% of patients who present to the hospital with ACS have a STEMI.[9]

Pathophysiology

An acute thrombotic coronary event leads to ST-segment elevation on a surface ECG after complete and persistent blood flow occlusion. Coronary atherosclerosis and the presence of a high-risk thin-cap fibroatheroma can result in sudden-onset plaque rupture.[10] This event results in vascular endothelium changes, producing a cascade of platelet adhesion, activation, and aggregation, ultimately leading to thrombosis.[11]

Coronary artery occlusion in animal models shows a "wave-front" of myocardial injury that spreads from the subendocardial myocardium to the subepicardial myocardium, resulting in a transmural infarction that produces ST-segment elevation on surface ECG.[12] Myocardial damage occurs when the blood flow is interrupted, warranting immediate management. Sudden-onset acute ischemia can result in severe microvascular dysfunction.

History and Physical

Acute chest discomfort, which patients may describe as pain, pressure, tightness, heaviness, or a burning sensation, is the most common symptom that leads healthcare professionals to consider the diagnosis of ACS and initiate appropriate diagnostic testing. Diagnostic delays or errors can occur from an incomplete patient history or challenges in obtaining a clear description of symptoms. Therefore, thorough patient history and detailed communication are essential to understand the complexity of ACS-related symptoms, potentially enabling a prompt and accurate diagnosis.

Obtaining a focused medical history and identifying the presenting symptoms is essential to quickly guide the patient along the appropriate care pathway. A targeted physical examination should involve evaluating all major pulses, measuring blood pressure in both arms, auscultating heart and lung sounds, and assessing for any signs of heart failure or circulatory compromise. Patients should be asked about the characteristics of the pain and associated symptoms, risk factors or history of cardiovascular disease, and recent drug use.[13]

STEMI risk factors include age, gender, family history of premature coronary artery disease, tobacco use, dyslipidemia, diabetes, hypertension, abdominal obesity, sedentary lifestyle, a diet low in fruits and vegetables, and psychosocial stressors.[14] Cocaine use can cause STEMI regardless of risk factors.[15] Obtaining a history of known congenital abnormalities can be useful during evaluation.[16] Familial hypercholesterolemia is linked to an increased risk of early-onset atherosclerotic disease. In patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction, familial hypercholesterolemia correlates with a higher incidence of both STEMI and NSTEMI, fewer cases of type 2 myocardial infarction, and Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, and a greater need for multiple stents, coronary bypass surgery, and mechanical circulatory support devices.[17]

Evaluation

Electrocardiogram

The resting 12-lead ECG is the primary diagnostic tool for evaluating patients with suspected ACS. An ECG should be performed immediately upon first medical contact and interpreted by a qualified emergency medical technician or physician within 10 minutes. Repeat ECGs may be necessary, mainly if symptoms have subsided during first medical contact.

Patients with suspected ACS are typically categorized into 2 main diagnostic groups based on the initial ECG findings.[18] Patients with acute chest pain or equivalent symptoms and persistent ST-segment elevation or its ECG equivalents are given a working diagnosis of STEMI. Most of these patients experience myocardial necrosis and elevated troponin levels, meeting the criteria for myocardial infarction, although not all will have a final diagnosis of STEMI. Patients with acute chest pain or equivalent symptoms without persistent ST-segment elevation or its ECG equivalents are categorized under non–ST-elevation ACS (NSTE-ACS).

Guidelines from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, European Society of Cardiology, and World Heart Federation

Evaluating patients with acute onset of chest pain should begin with an ECG and troponin levels. The American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), ESC, and the World Heart Federation (WHF) committee established the following ECG criteria for STEMI:

- New ST-segment elevation occurs at the J point in 2 contiguous leads, with a threshold greater than 0.1 mV in all leads except V2 and V3.

- In leads V2 and V3, the threshold is greater than 0.2 mV for men older than 40, greater than 0.25 mV for men under 40, and greater than 0.15 mV for women.[19]

Promptly identifying occlusion myocardial infarction (OMI) in patients with acute chest pain is crucial to enable rapid revascularization. In left bundle branch block (LBBB) cases, interpreting the ECG can be particularly challenging due to ST-segment changes associated with this pattern. The Sgarbossa criteria were developed to enhance the detection of acute myocardial infarction in patients with LBBB, relying on the concordance between the QRS complex and the ST segment.[20] Typically, in an ECG with LBBB without OMI, the "principle of appropriate discordance" applies. The ST segment is oriented opposite to the QRS complex, which means that in leads where the QRS is predominantly positive, the ST segment is negative. Conversely, the ST segment is elevated in leads with a predominantly negative QRS complex.

In OMI cases, the ST segment may show "concordant" changes with the QRS or exhibit "excessive" discordant elevation. The Sgarbossa criteria include this excessively discordant ST elevation (greater than 0.5 mV) as a 3rd criterion, along with concordant ST-segment changes. While these criteria are highly specific, their sensitivity for detecting OMI is limited.[21]

Patients with a preexisting LBBB can be further evaluated using the Sgarbossa criteria:

- ST-segment elevation of 1 mm or more that is concordant with or in the same direction as the QRS complex

- ST-segment depression of 1 mm or more in lead V1, V2, or V3

- ST-segment elevation of 5 mm or more (that is discordant with or in the opposite direction of the QRS complex)[22]

The ACC, AHA, and Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions (SCAI) have issued class I recommendations based on recent evidence.[23] For patients experiencing STEMI with ischemic symptoms lasting less than 12 hours, PCI is recommended to enhance survival outcomes. In cases of STEMI where reperfusion following fibrinolytic therapy is unsuccessful, performing rescue PCI on the infarct-related artery is advised to improve clinical outcomes. Primary PCI is recommended for patients with STEMI who present with cardiogenic shock or acute severe heart failure, regardless of the time elapsed since the onset of the myocardial infarction.[23]

Cardiac Biomarkers

Once STEMI and very high-risk NSTE-ACS are ruled out, biomarkers become essential for confirming the diagnosis, assessing risk, and managing suspected cases of ACS. Measuring a biomarker of cardiomyocyte injury, such as high-sensitivity cardiac troponin (hs-cTn), is recommended for all patients with suspected ACS. If the clinical presentation aligns with myocardial ischemia, an elevation or decrease in hs-cTn levels above the 99th percentile of a healthy population supports the diagnosis of myocardial infarction, according to the 4th universal definition of this condition.[24]

Hs-cTn assays offer greater sensitivity and diagnostic precision for detecting myocardial infarction upon presentation, allowing for a shorter interval between the first and second troponin measurements. Timely serial measurements lead to faster diagnosis and reduce emergency department stays, healthcare costs, and patient diagnostic uncertainty.[25] The preferred approach is the 0-hour/1-hour algorithm, with the 0-hour/2-hour algorithm as an alternative. These algorithms have been developed and validated through extensive multicenter diagnostic studies using centralized adjudication of the final diagnosis for all currently available hs-cTn assays.[26]

Transthoracic Echocardiogram

For patients with suspected ACS where the diagnosis is uncertain, transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) can help identify signs indicative of ongoing ischemia or previous myocardial infarction. However, the use of TTE should not cause significant delays in transferring the patient to the cardiac catheterization laboratory if an acute coronary artery occlusion is suspected. Additionally, TTE can help identify other potential causes of chest pain, such as acute aortic disease and right ventricular signs associated with pulmonary embolism.

Computed Tomography

Computed tomography (CT) is frequently the preferred diagnostic tool when excluding other potentially life-threatening conditions that may mimic ACS, such as pulmonary embolism and aortic dissection. An ECG-gated contrast CT angiogram covering the entire thoracic aorta and proximal head and neck vessels is recommended in these cases. However, CT is generally not indicated for patients suspected of having an ongoing acute coronary occlusion, where immediate invasive coronary angiography is the priority.

Treatment / Management

After diagnosing acute STEMI, intravenous access should be obtained, and cardiac monitoring should be started. Timely treatment is crucial for patients classified under the STEMI pathway. Key factors include the total ischemic time, sources of delays in initial management, and the choice of reperfusion strategy for patients with STEMI. The efficiency and quality of care a system provides for individuals with suspected STEMI are reflected in these treatment times. Patients who are hypoxemic or at risk for hypoxemia benefit from oxygen therapy. However, results from recent studies show possible harmful effects in patients who are normoxic.[27][28] Patients should undergo PCI within 90 minutes of presentation at a PCI-capable hospital or within 120 minutes if transfer to a PCI-capable hospital is required.

If PCI is not possible within 120 minutes of first medical contact, fibrinolytic therapy should be initiated within 30 minutes of the patient's arrival at the hospital.[29] Patients should be promptly transferred to a PCI center after starting lytic therapy. If fibrinolysis fails or signs of reocclusion or reinfarction, such as recurring ST-segment elevation, emerge, immediate angiography and rescue PCI is necessary.[30] Further administration of fibrinolytic is not recommended in such cases. Even when fibrinolysis appears successful, as indicated by significant resolution of ST-segment elevation (ie, >50% at 60–90 minutes), typical reperfusion arrhythmias, and relief of chest pain, early angiography within 2 to 24 hours is still advised.[31] Conditions that can mimic ACS, such as acute aortic dissection and pulmonary embolism, must be ruled out.(B3)

Manual thrombus aspiration before PCI in patients with STEMI is a quick and cost-effective technique to reduce microvascular obstruction following PCI.[32] While the TAPAS study (Thrombus Aspiration During Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Acute Myocardial Infarction) initially suggested that thrombus aspiration before PCI could offer clinical benefits compared to PCI alone, subsequent research and meta-analyses did not significantly improve clinical outcomes.[33](A1)

Additionally, concerns about patient safety have emerged, with evidence demonstrating a higher risk of stroke in those undergoing thrombus aspiration compared to PCI alone, both at 1 month and 1 year postprocedure.[34][35] Reflecting these findings, the 2023 ESC guidelines for managing ACS advise against routine thrombus aspiration (Class III, Level of Evidence A). However, the guidelines suggest that thrombus aspiration may be considered in certain STEMI cases, particularly those with a high thrombotic burden following PCI.

Pharmacological Therapy

Nitroglycerin administration can reduce anginal pain. However, this drug should be avoided in patients who have used phosphodiesterase-inhibiting medication within the last 24 hours and in cases of right ventricular infarction. Morphine can be given for further pain relief to patients who continue to report discomfort after nitroglycerin administration. However, reasonable use is not recommended, as it may adversely affect outcomes.[36](B2)

All patients with an acute myocardial infarction should be started on a beta blocker, high-intensity statin, aspirin, and a P2Y12 inhibitor as soon as possible, with certain exceptions. Aspirin therapy for ACS begins with a loading dose administered as early as possible, followed by a maintenance dose of 75 to 100 mg once daily.[37] Based on the results from the PLATO (PLATlet inhibition and patient Outcomes) and TRITON-TIMI 38 (Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet Inhibition With Prasurgrel-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 38) studies, dual antiplatelet therapy combining aspirin with a potent P2Y12 receptor inhibitor, such as prasugrel or ticagrelor, is the recommended strategy for most individuals with ACS.[38] Clopidogrel, which has less potent and more variable effects on platelet inhibition, should be reserved for cases where prasugrel and ticagrelor are contraindicated or unavailable or in patients with a high bleeding risk, defined as those meeting 1 major or 2 minor Antithrombotic Treatment for High Bleeding Risk criteria.[39] Clopidogrel may also be considered in patients aged 70 or older.[40](A1)

P2Y-inhibiting antiplatelet medication choice depends on whether the patient underwent PCI or fibrinolytic therapy. Due to results from recent trials showing superiority, ticagrelor and prasugrel are preferred over clopidogrel in patients who undergo PCI.[41] Individuals undergoing fibrinolytic therapy should be started on clopidogrel.[42] The relative contraindications of P2Y12 inhibitors should always be considered. Prasugrel is contraindicated in patients with a history of transient ischemic attack and stroke. Anticoagulation should also be started alongside unfractionated heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin, bivalirudin, or fondaparinux.[43] Lipid-lowering therapy must be initiated as soon as possible following an ACS event, as the treatment is crucial for improving long-term prognosis and enhancing patient adherence after discharge. High-intensity statins, such as atorvastatin and rosuvastatin, should be started early, ideally before any planned PCI, and prescribed at the highest tolerated dose to achieve target low-density lipoprotein-C levels.[44](A1)

Recent studies support β-blocker benefits in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) after ACS. However, the evidence for using these drugs in patients with LVEF greater than 40% following uncomplicated ACS is less definitive.[45] Except for the results from the CAPRICORN trial (CArvedilol Post-infaRct survIval COntRolled evaluatioN), which focused on patients with LVEF less than or equal to 40%, most large randomized controlled trials evaluating postmyocardial infarction β-blocker therapy were conducted before the widespread use of reperfusion therapies.[46](A1)

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors have been shown to improve postmyocardial infarction outcomes in patients with conditions such as heart failure, LVEF less than or equal to 40%, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and hypertension.[47] Historical trials of ACE inhibitors in STEMI have indicated a modest but significant reduction in 30-day mortality, particularly in cases of anterior myocardial infarction.[48] Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors improve glycemic control and reduce weight and blood pressure by inducing glycosuria and lowering plasma glucose levels without causing hypoglycemia.[49] In patients with type 2 diabetes and established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, trials of empagliflozin, canagliflozin, and dapagliflozin have demonstrated notable cardiovascular benefits.[50](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

Other pathologies that can cause ST-segment elevation include myocarditis, pericarditis, stress cardiomyopathy (Takotsubo), benign early repolarization, acute vasospasm (Prinzmetal), spontaneous coronary artery dissection, LBBB, various channelopathies, and electrolyte abnormalities. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, often referred to as "broken heart syndrome," is a distinct cardiac condition that has garnered increased interest in recent years.[51] Originally identified in Japan in the early 1990s, this syndrome is marked by abrupt and profound dysfunction of the left ventricle, frequently precipitated by intense emotional stress or major life events. Unlike a conventional myocardial infarction caused by blocked coronary arteries, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy occurs without significant coronary obstructions, setting it apart as a unique and perplexing cardiac disorder.[52]

Prinzmetal angina, or vasospastic angina (VSA), arises from spontaneous coronary artery spasms, which can result in serious complications, particularly in individuals with increased coronary vasoconstriction and reduced vasodilation.[53] Early identification of patients at risk is crucial to prevent severe or fatal outcomes. While the exact prevalence of VSA remains uncertain, a study in Japan found that it may affect around 40% of individuals with angina, possibly higher than in White populations due to differences in clinical testing methods.[54] The primary treatment strategy involves using vasodilators and managing risk factors, such as smoking, hypertension, diabetes, lipid levels, stress, and alcohol consumption. VSA may also be linked to migraines.

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is characterized by a tear in the epicardial coronary arteries, neither caused by medical procedures nor related to trauma or atherosclerosis.[55] Unlike the intraluminal thrombosis or plaque rupture that typically leads to ACS, SCAD-induced ACS results from myocardial damage from coronary artery obstruction following intimal disruption or the formation of an intramural hematoma, which creates a false lumen. SCAD predominantly affects individuals who lack traditional atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk factors and is more frequently observed in younger women without underlying atherosclerotic disease.[56] Symptoms can vary widely, from chest pain to sudden cardiac death. Despite greater awareness and advancements in intravascular imaging, SCAD remains frequently underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed, often being mistaken for atherosclerotic disease.

Prognosis

The Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) risk score is a straightforward tool that uses 8 prognostic factors to evaluate the risk associated with STEMI at the bedside. The TIMI risk score is the most commonly used scoring system for 30-day mortality.[57] This scoring system incorporates:

- Age older than 75 is assigned 3 points. Age between 64 and 74 is assigned 2 points.

- Diabetes, hypertension, or a history of angina is assigned 1 point.

- A systolic blood pressure less than 100 mm Hg is assigned 3 points.

- A heart rate greater than 100 beats per minute is assigned 2 points.

- Killip class II to IV is assigned 2 points.

- A body weight less than 150 lbs is assigned 1 point.

The TIMI score ranges from 0 to 14, with each point representing a different level of risk based on the patient’s condition.[58] This scoring system helps predict mortality within the first 30 days following STEMI and is reliable for forecasting outcomes in patients receiving fibrinolytic therapy.[59] Studies have applied the TIMI score to estimate mortality rates in anterior wall STEMI cases. The TIMI score can help classify patients based on risk categories. Risk levels are categorized as low for scores ranging from 0 to 4, medium for scores between 5 and 9, and high for scores above 9. Mortality rates at 30 days for patients presenting with STEMI are between 2.5% and 10%.[60][61][62]

Complications

Myocardial infarction has 3 life-threatening mechanical complications: ventricular free wall rupture, interventricular septum rupture, and acute mitral regurgitation. Ventricular free wall rupture occurs within 5 days in half the cases and 2 weeks in 90% of cases, with an overall mortality rate of greater than 80%.[63][64] Interventricular septum rupture is reported about half as often as free wall rupture and typically occurs in 3 to 5 days, with an overall mortality rate greater than 70%.[65][66] Prompt surgery reduces the mortality rate in both conditions. Acute mitral regurgitation following a myocardial infarction is most commonly due to ischemic papillary muscle displacement, left ventricular dilatation, or rupture of the papillary muscle or chordae. In STEMI, the degree of mitral regurgitation is usually severe and associated with a 30-day survival of 24%.[67]

Inflammation of the pericardium, known as pericarditis, and pericardial effusion resulting from pericardial injury are collectively referred to as postcardiac injury syndrome. This syndrome includes conditions such as postmyocardial infarction, pericarditis (Dressler syndrome), postpericardiotomy syndrome, and posttraumatic pericarditis. Even minor injuries, like those from PCI, cardiac implantable electronic device placement, or radiofrequency ablation, can provoke cardiac injury. These conditions share a common trigger of pericardial or pleural damage, leading to a pleuropericardial syndrome characterized by pericarditis with pericardial effusion and pleural effusion.[68]

Pearls and Other Issues

Critical considerations in managing STEMI include the following:

- Chest pain or discomfort: This symptom is the primary trigger for the diagnostic and treatment processes in acute coronary syndrome.

- Coordination between emergency medical services and hospitals: Effective STEMI management relies on the seamless coordination between emergency medical services (EMS) and hospitals, facilitated by standardized written protocols. EMS should notify the PCI center as soon as a reperfusion strategy is decided, and the patient should be directly transferred to the PCI center, bypassing the emergency department.

- Invasive strategy: An invasive approach is advised for patients with ACS due to the condition's time-sensitive nature. Immediate invasive intervention is strongly recommended for STEMI.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A door-to-balloon time of less than 90 minutes is the goal of a PCI-capable facility. This parameter is one of the core measures of the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations.[69] The door-to-balloon time is the time between the patient's arrival in the emergency department and the crossing of the culprit lesion by a guide wire in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. Teamwork between EMS, emergency department physicians, and interventional cardiologists sets the groundwork for optimal door-to-balloon times. The median door-to-balloon time in 2010 was 64 minutes, with 91% of patients receiving PCI in under 90 minutes and 70% in under 75 minutes.[70]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

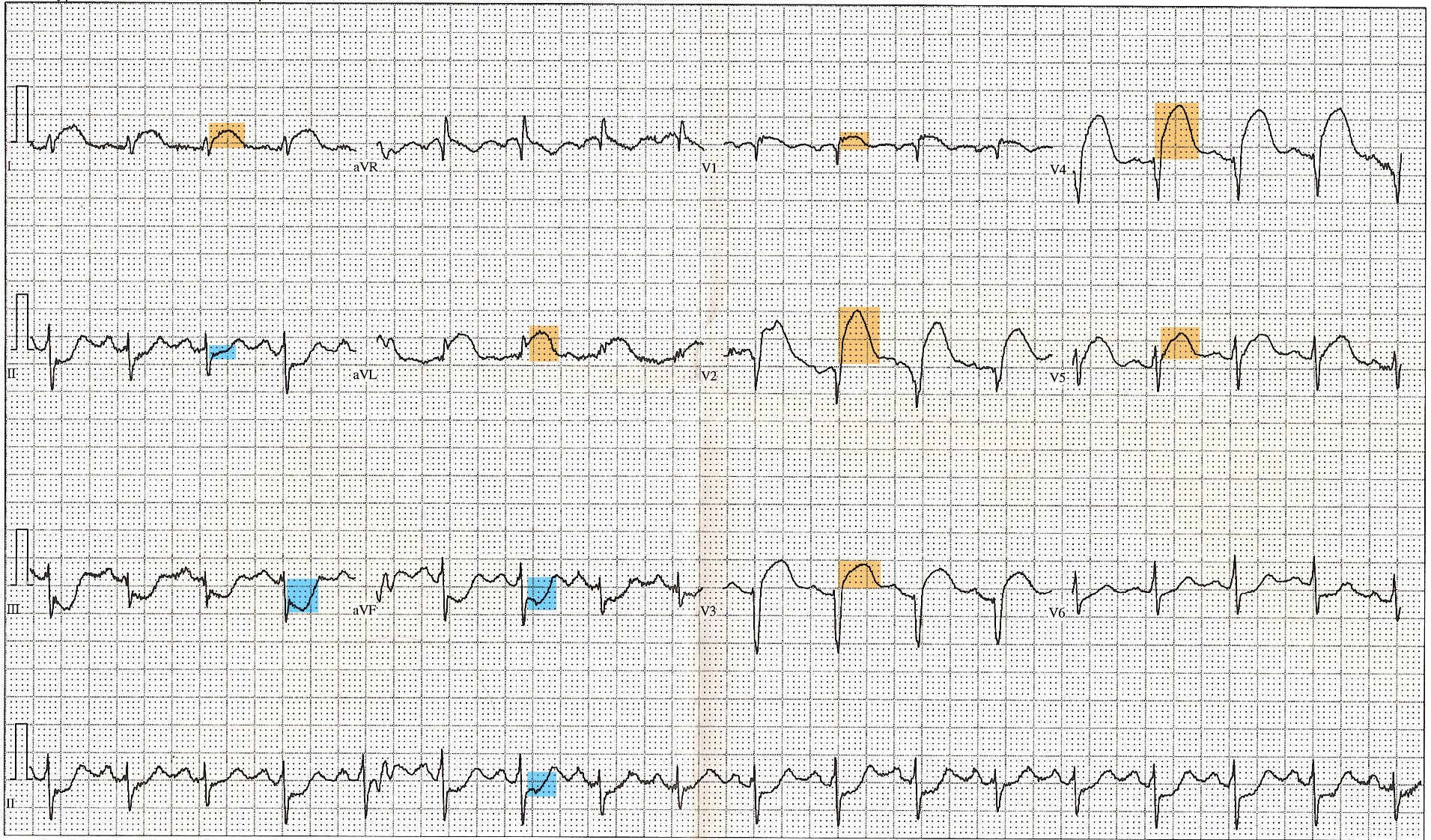

ST-Elevated Myocardial Infarction on Electrocardiogram. This 12-lead electrocardiogram shows ST elevation in the anterior (orange) and inferior (blue) leads. Tachycardia and anterior fascicular block are also noted. A diagnosis of ST-elevated myocardial infarction can be made, along with clinical evaluation and cardiac marker elevation.

Displaced, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

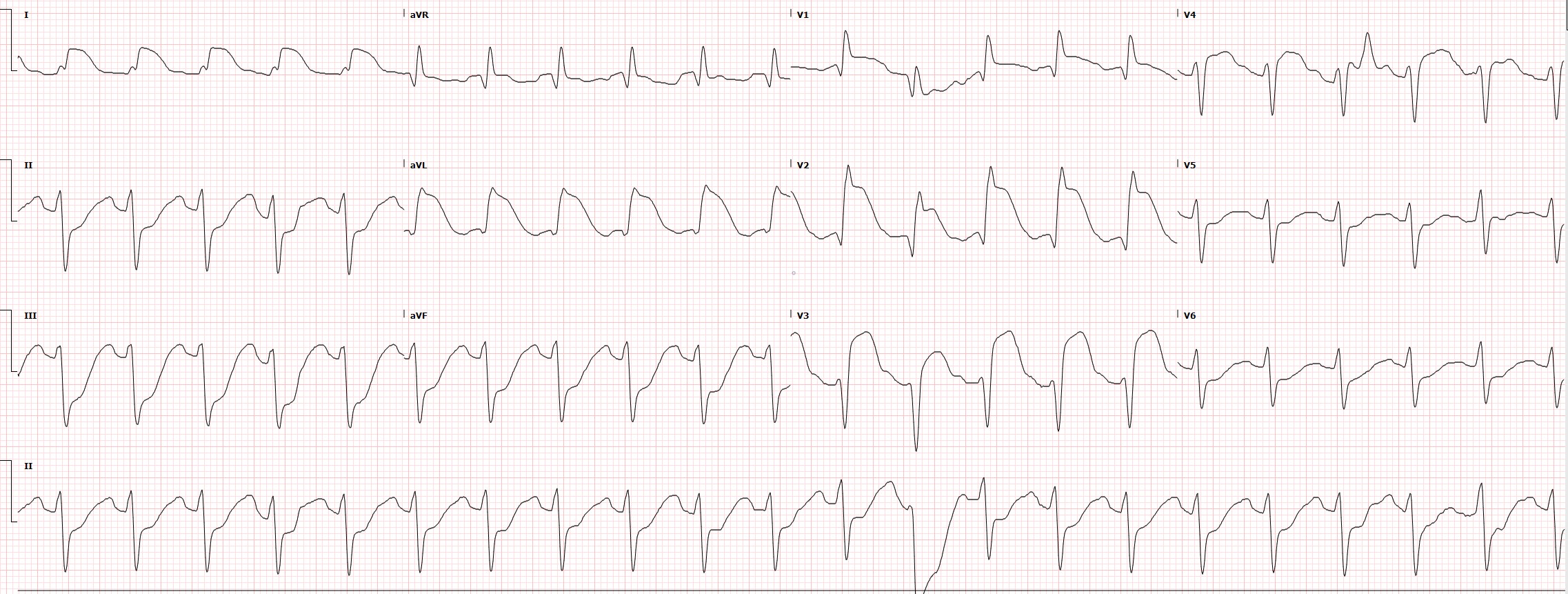

Electrocardiogram Tracing for a Case of Proximal Left Anterior Descending Occlusion. This electrocardiogram strip is taken from a case of proximal left anterior descending (LAD) occlusion. ST elevation is seen in the anterior (V3, V4), septal (V1, V2), and high lateral (I, aVL) infarction. Reciprocal changes are notable in the inferior leads (II, III, aVF).

Contributed by C Foth, DO

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, Bassand JP. Myocardial infarction redefined--a consensus document of The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2000 Sep:36(3):959-69 [PubMed PMID: 10987628]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceThygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Chaitman BR, Bax JJ, Morrow DA, White HD, ESC Scientific Document Group. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). European heart journal. 2019 Jan 14:40(3):237-269. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy462. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30165617]

Bhatt DL, Lopes RD, Harrington RA. Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Review. JAMA. 2022 Feb 15:327(7):662-675. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.0358. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35166796]

Hartikainen TS, Sörensen NA, Haller PM, Goßling A, Lehmacher J, Zeller T, Blankenberg S, Westermann D, Neumann JT. Clinical application of the 4th Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. European heart journal. 2020 Jun 14:41(23):2209-2216. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa035. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32077925]

Cohen M, Visveswaran G. Defining and managing patients with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: Sorting through type 1 vs other types. Clinical cardiology. 2020 Mar:43(3):242-250. doi: 10.1002/clc.23308. Epub 2020 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 31923336]

Wilson PW. Established risk factors and coronary artery disease: the Framingham Study. American journal of hypertension. 1994 Jul:7(7 Pt 2):7S-12S [PubMed PMID: 7946184]

Canto JG, Kiefe CI, Rogers WJ, Peterson ED, Frederick PD, French WJ, Gibson CM, Pollack CV Jr, Ornato JP, Zalenski RJ, Penney J, Tiefenbrunn AJ, Greenland P, NRMI Investigators. Number of coronary heart disease risk factors and mortality in patients with first myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2011 Nov 16:306(19):2120-7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1654. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22089719]

Timmis A, Vardas P, Townsend N, Torbica A, Katus H, De Smedt D, Gale CP, Maggioni AP, Petersen SE, Huculeci R, Kazakiewicz D, de Benito Rubio V, Ignatiuk B, Raisi-Estabragh Z, Pawlak A, Karagiannidis E, Treskes R, Gaita D, Beltrame JF, McConnachie A, Bardinet I, Graham I, Flather M, Elliott P, Mossialos EA, Weidinger F, Achenbach S, Atlas Writing Group, European Society of Cardiology. European Society of Cardiology: cardiovascular disease statistics 2021. European heart journal. 2022 Feb 22:43(8):716-799. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab892. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35016208]

Writing Group Members, Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, de Ferranti S, Després JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, McGuire DK, Mohler ER 3rd, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Rosamond W, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB, American Heart Association Statistics Committee, Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016 Jan 26:133(4):e38-360. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. Epub 2015 Dec 16 [PubMed PMID: 26673558]

Kolodgie FD, Burke AP, Farb A, Gold HK, Yuan J, Narula J, Finn AV, Virmani R. The thin-cap fibroatheroma: a type of vulnerable plaque: the major precursor lesion to acute coronary syndromes. Current opinion in cardiology. 2001 Sep:16(5):285-92 [PubMed PMID: 11584167]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceScharf RE. Platelet Signaling in Primary Haemostasis and Arterial Thrombus Formation: Part 1. Hamostaseologie. 2018 Nov:38(4):203-210. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1675144. Epub 2018 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 30352470]

Reimer KA, Jennings RB. The "wavefront phenomenon" of myocardial ischemic cell death. II. Transmural progression of necrosis within the framework of ischemic bed size (myocardium at risk) and collateral flow. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology. 1979 Jun:40(6):633-44 [PubMed PMID: 449273]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAmsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, Casey DE Jr, Ganiats TG, Holmes DR Jr, Jaffe AS, Jneid H, Kelly RF, Kontos MC, Levine GN, Liebson PR, Mukherjee D, Peterson ED, Sabatine MS, Smalling RW, Zieman SJ. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients with Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014 Dec 23:64(24):e139-e228. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.017. Epub 2014 Sep 23 [PubMed PMID: 25260718]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTorpy JM, Burke AE, Glass RM. JAMA patient page. Coronary heart disease risk factors. JAMA. 2009 Dec 2:302(21):2388. doi: 10.1001/jama.302.21.2388. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19952328]

McCord J, Jneid H, Hollander JE, de Lemos JA, Cercek B, Hsue P, Gibler WB, Ohman EM, Drew B, Philippides G, Newby LK, American Heart Association Acute Cardiac Care Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology. Management of cocaine-associated chest pain and myocardial infarction: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Acute Cardiac Care Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology. Circulation. 2008 Apr 8:117(14):1897-907. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.188950. Epub 2008 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 18347214]

Akbar H, Kahloon A, Kahloon R. Diagnostic Challenge in a Symptomatic Patient of Arteria Lusoria with Retro-esophageal Right Subclavian Artery and Absent Brachiocephalic Trunk. Cureus. 2020 Feb 18:12(2):e7029. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7029. Epub 2020 Feb 18 [PubMed PMID: 32117665]

Kumi D, Narh JT, Odoi SM, Oduro A, Gajjar R, Gwira-Tamattey E, Karki S, Abbasi A, Fugar S, Alyousef T. Current US prevalence of myocardial injury patterns and clinical outcomes among hospitalised patients with familial hypercholesterolaemia: insight from the National Inpatient Sample-a retrospective cohort study. BMJ open. 2024 May 28:14(5):e077839. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-077839. Epub 2024 May 28 [PubMed PMID: 38806434]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceIbanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, Prescott E, Roffi M, Valgimigli M, Varenhorst C, Vranckx P, Widimský P, ESC Scientific Document Group. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European heart journal. 2018 Jan 7:39(2):119-177. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28886621]

Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR, White HD, Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction, Katus HA, Lindahl B, Morrow DA, Clemmensen PM, Johanson P, Hod H, Underwood R, Bax JJ, Bonow RO, Pinto F, Gibbons RJ, Fox KA, Atar D, Newby LK, Galvani M, Hamm CW, Uretsky BF, Steg PG, Wijns W, Bassand JP, Menasché P, Ravkilde J, Ohman EM, Antman EM, Wallentin LC, Armstrong PW, Simoons ML, Januzzi JL, Nieminen MS, Gheorghiade M, Filippatos G, Luepker RV, Fortmann SP, Rosamond WD, Levy D, Wood D, Smith SC, Hu D, Lopez-Sendon JL, Robertson RM, Weaver D, Tendera M, Bove AA, Parkhomenko AN, Vasilieva EJ, Mendis S. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2012 Oct 16:126(16):2020-35. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31826e1058. Epub 2012 Aug 24 [PubMed PMID: 22923432]

Sgarbossa EB, Pinski SL, Barbagelata A, Underwood DA, Gates KB, Topol EJ, Califf RM, Wagner GS. Electrocardiographic diagnosis of evolving acute myocardial infarction in the presence of left bundle-branch block. GUSTO-1 (Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries) Investigators. The New England journal of medicine. 1996 Feb 22:334(8):481-7 [PubMed PMID: 8559200]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKhawaja M, Thakker J, Kherallah R, Ye Y, Smith SW, Birnbaum Y. Diagnosis of Occlusion Myocardial Infarction in Patients with Left Bundle Branch Block and Paced Rhythms. Current cardiology reports. 2021 Nov 17:23(12):187. doi: 10.1007/s11886-021-01613-0. Epub 2021 Nov 17 [PubMed PMID: 34791609]

Smith SW, Dodd KW, Henry TD, Dvorak DM, Pearce LA. Diagnosis of ST-elevation myocardial infarction in the presence of left bundle branch block with the ST-elevation to S-wave ratio in a modified Sgarbossa rule. Annals of emergency medicine. 2012 Dec:60(6):766-76. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.07.119. Epub 2012 Aug 31 [PubMed PMID: 22939607]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceByrne RA, Rossello X, Coughlan JJ, Barbato E, Berry C, Chieffo A, Claeys MJ, Dan GA, Dweck MR, Galbraith M, Gilard M, Hinterbuchner L, Jankowska EA, Jüni P, Kimura T, Kunadian V, Leosdottir M, Lorusso R, Pedretti RFE, Rigopoulos AG, Rubini Gimenez M, Thiele H, Vranckx P, Wassmann S, Wenger NK, Ibanez B, ESC Scientific Document Group. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. European heart journal. 2023 Oct 12:44(38):3720-3826. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad191. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37622654]

Anand A, Lee KK, Chapman AR, Ferry AV, Adamson PD, Strachan FE, Berry C, Findlay I, Cruikshank A, Reid A, Collinson PO, Apple FS, McAllister DA, Maguire D, Fox KAA, Newby DE, Tuck C, Harkess R, Keerie C, Weir CJ, Parker RA, Gray A, Shah ASV, Mills NL, HiSTORIC Investigators†. High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin on Presentation to Rule Out Myocardial Infarction: A Stepped-Wedge Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Circulation. 2021 Jun 8:143(23):2214-2224. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.052380. Epub 2021 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 33752439]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWildi K, Boeddinghaus J, Nestelberger T, Twerenbold R, Badertscher P, Wussler D, Giménez MR, Puelacher C, du Fay de Lavallaz J, Dietsche S, Walter J, Kozhuharov N, Morawiec B, Miró Ò, Javier Martin-Sanchez F, Subramaniam S, Geigy N, Keller DI, Reichlin T, Mueller C, APACE investigators. Comparison of fourteen rule-out strategies for acute myocardial infarction. International journal of cardiology. 2019 May 15:283():41-47. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.11.140. Epub 2018 Dec 3 [PubMed PMID: 30545622]

Boeddinghaus J, Nestelberger T, Lopez-Ayala P, Koechlin L, Buechi M, Miro O, Keller DI, Gimenez MR, Twerenbold R, Mueller C, APACE Investigators. Diagnostic Performance of the European Society of Cardiology 0/1-h Algorithms in Late Presenters. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2021 Mar 9:77(9):1264-1267. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.01.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33663745]

Stub D, Smith K, Bernard S, Nehme Z, Stephenson M, Bray JE, Cameron P, Barger B, Ellims AH, Taylor AJ, Meredith IT, Kaye DM, AVOID Investigators. Air Versus Oxygen in ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 2015 Jun 16:131(24):2143-50. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014494. Epub 2015 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 26002889]

Hofmann R, James SK, Jernberg T, Lindahl B, Erlinge D, Witt N, Arefalk G, Frick M, Alfredsson J, Nilsson L, Ravn-Fischer A, Omerovic E, Kellerth T, Sparv D, Ekelund U, Linder R, Ekström M, Lauermann J, Haaga U, Pernow J, Östlund O, Herlitz J, Svensson L, DETO2X–SWEDEHEART Investigators. Oxygen Therapy in Suspected Acute Myocardial Infarction. The New England journal of medicine. 2017 Sep 28:377(13):1240-1249. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706222. Epub 2017 Aug 28 [PubMed PMID: 28844200]

O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE Jr, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, Ettinger SM, Fang JC, Fesmire FM, Franklin BA, Granger CB, Krumholz HM, Linderbaum JA, Morrow DA, Newby LK, Ornato JP, Ou N, Radford MJ, Tamis-Holland JE, Tommaso CL, Tracy CM, Woo YJ, Zhao DX, Anderson JL, Jacobs AK, Halperin JL, Albert NM, Brindis RG, Creager MA, DeMets D, Guyton RA, Hochman JS, Kovacs RJ, Kushner FG, Ohman EM, Stevenson WG, Yancy CW, American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013 Jan 29:127(4):e362-425. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742cf6. Epub 2012 Dec 17 [PubMed PMID: 23247304]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceArbel Y, Ko DT, Yan AT, Cantor WJ, Bagai A, Koh M, Eberg M, Tan M, Fitchett D, Borgundvaag B, Ducas J, Heffernan M, Morrison LJ, Langer A, Dzavik V, Mehta SR, Goodman SG, TRANSFER-AMI Trial Investigators. Long-term Follow-up of the Trial of Routine Angioplasty and Stenting After Fibrinolysis to Enhance Reperfusion in Acute Myocardial Infarction (TRANSFER-AMI). The Canadian journal of cardiology. 2018 Jun:34(6):736-743. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2018.02.005. Epub 2018 Feb 10 [PubMed PMID: 29801739]

Gershlick AH, Stephens-Lloyd A, Hughes S, Abrams KR, Stevens SE, Uren NG, de Belder A, Davis J, Pitt M, Banning A, Baumbach A, Shiu MF, Schofield P, Dawkins KD, Henderson RA, Oldroyd KG, Wilcox R, REACT Trial Investigators. Rescue angioplasty after failed thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. The New England journal of medicine. 2005 Dec 29:353(26):2758-68 [PubMed PMID: 16382062]

de Waha S, Patel MR, Granger CB, Ohman EM, Maehara A, Eitel I, Ben-Yehuda O, Jenkins P, Thiele H, Stone GW. Relationship between microvascular obstruction and adverse events following primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: an individual patient data pooled analysis from seven randomized trials. European heart journal. 2017 Dec 14:38(47):3502-3510. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx414. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29020248]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVlaar PJ, Svilaas T, van der Horst IC, Diercks GF, Fokkema ML, de Smet BJ, van den Heuvel AF, Anthonio RL, Jessurun GA, Tan ES, Suurmeijer AJ, Zijlstra F. Cardiac death and reinfarction after 1 year in the Thrombus Aspiration during Percutaneous coronary intervention in Acute myocardial infarction Study (TAPAS): a 1-year follow-up study. Lancet (London, England). 2008 Jun 7:371(9628):1915-20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60833-8. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18539223]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLagerqvist B, Fröbert O, Olivecrona GK, Gudnason T, Maeng M, Alström P, Andersson J, Calais F, Carlsson J, Collste O, Götberg M, Hårdhammar P, Ioanes D, Kallryd A, Linder R, Lundin A, Odenstedt J, Omerovic E, Puskar V, Tödt T, Zelleroth E, Östlund O, James SK. Outcomes 1 year after thrombus aspiration for myocardial infarction. The New England journal of medicine. 2014 Sep 18:371(12):1111-20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1405707. Epub 2014 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 25176395]

Jolly SS,Cairns JA,Lavi S,Cantor WJ,Bernat I,Cheema AN,Moreno R,Kedev S,Stankovic G,Rao SV,Meeks B,Chowdhary S,Gao P,Sibbald M,Velianou JL,Mehta SR,Tsang M,Sheth T,Džavík V, Thrombus Aspiration in Patients With High Thrombus Burden in the TOTAL Trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018 Oct 2; [PubMed PMID: 30261959]

Meine TJ, Roe MT, Chen AY, Patel MR, Washam JB, Ohman EM, Peacock WF, Pollack CV Jr, Gibler WB, Peterson ED, CRUSADE Investigators. Association of intravenous morphine use and outcomes in acute coronary syndromes: results from the CRUSADE Quality Improvement Initiative. American heart journal. 2005 Jun:149(6):1043-9 [PubMed PMID: 15976786]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJones WS, Mulder H, Wruck LM, Pencina MJ, Kripalani S, Muñoz D, Crenshaw DL, Effron MB, Re RN, Gupta K, Anderson RD, Pepine CJ, Handberg EM, Manning BR, Jain SK, Girotra S, Riley D, DeWalt DA, Whittle J, Goldberg YH, Roger VL, Hess R, Benziger CP, Farrehi P, Zhou L, Ford DE, Haynes K, VanWormer JJ, Knowlton KU, Kraschnewski JL, Polonsky TS, Fintel DJ, Ahmad FS, McClay JC, Campbell JR, Bell DS, Fonarow GC, Bradley SM, Paranjape A, Roe MT, Robertson HR, Curtis LH, Sharlow AG, Berdan LG, Hammill BG, Harris DF, Qualls LG, Marquis-Gravel G, Modrow MF, Marcus GM, Carton TW, Nauman E, Waitman LR, Kho AN, Shenkman EA, McTigue KM, Kaushal R, Masoudi FA, Antman EM, Davidson DR, Edgley K, Merritt JG, Brown LS, Zemon DN, McCormick TE 3rd, Alikhaani JD, Gregoire KC, Rothman RL, Harrington RA, Hernandez AF, ADAPTABLE Team. Comparative Effectiveness of Aspirin Dosing in Cardiovascular Disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2021 May 27:384(21):1981-1990. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2102137. Epub 2021 May 15 [PubMed PMID: 33999548]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Montalescot G, Ruzyllo W, Gottlieb S, Neumann FJ, Ardissino D, De Servi S, Murphy SA, Riesmeyer J, Weerakkody G, Gibson CM, Antman EM, TRITON-TIMI 38 Investigators. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. The New England journal of medicine. 2007 Nov 15:357(20):2001-15 [PubMed PMID: 17982182]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGimbel M, Qaderdan K, Willemsen L, Hermanides R, Bergmeijer T, de Vrey E, Heestermans T, Tjon Joe Gin M, Waalewijn R, Hofma S, den Hartog F, Jukema W, von Birgelen C, Voskuil M, Kelder J, Deneer V, Ten Berg J. Clopidogrel versus ticagrelor or prasugrel in patients aged 70 years or older with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome (POPular AGE): the randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet (London, England). 2020 Apr 25:395(10233):1374-1381. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30325-1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32334703]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHusted S, James S, Becker RC, Horrow J, Katus H, Storey RF, Cannon CP, Heras M, Lopes RD, Morais J, Mahaffey KW, Bach RG, Wojdyla D, Wallentin L, PLATO study group. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in elderly patients with acute coronary syndromes: a substudy from the prospective randomized PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial. Circulation. Cardiovascular quality and outcomes. 2012 Sep 1:5(5):680-8 [PubMed PMID: 22991347]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, Cannon CP, Emanuelsson H, Held C, Horrow J, Husted S, James S, Katus H, Mahaffey KW, Scirica BM, Skene A, Steg PG, Storey RF, Harrington RA, PLATO Investigators, Freij A, Thorsén M. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. The New England journal of medicine. 2009 Sep 10:361(11):1045-57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904327. Epub 2009 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 19717846]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSabatine MS, Cannon CP, Gibson CM, López-Sendón JL, Montalescot G, Theroux P, Claeys MJ, Cools F, Hill KA, Skene AM, McCabe CH, Braunwald E, CLARITY-TIMI 28 Investigators. Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin and fibrinolytic therapy for myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation. The New England journal of medicine. 2005 Mar 24:352(12):1179-89 [PubMed PMID: 15758000]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBraun M, Kassop D. Acute Coronary Syndrome: Management. FP essentials. 2020 Mar:490():20-28 [PubMed PMID: 32150365]

Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, Koskinas KC, Casula M, Badimon L, Chapman MJ, De Backer GG, Delgado V, Ference BA, Graham IM, Halliday A, Landmesser U, Mihaylova B, Pedersen TR, Riccardi G, Richter DJ, Sabatine MS, Taskinen MR, Tokgozoglu L, Wiklund O, ESC Scientific Document Group. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. European heart journal. 2020 Jan 1:41(1):111-188. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31504418]

Dahl Aarvik M, Sandven I, Dondo TB, Gale CP, Ruddox V, Munkhaugen J, Atar D, Otterstad JE. Effect of oral β-blocker treatment on mortality in contemporary post-myocardial infarction patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European heart journal. Cardiovascular pharmacotherapy. 2019 Jan 1:5(1):12-20. doi: 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvy034. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30192930]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDargie HJ. Effect of carvedilol on outcome after myocardial infarction in patients with left-ventricular dysfunction: the CAPRICORN randomised trial. Lancet (London, England). 2001 May 5:357(9266):1385-90 [PubMed PMID: 11356434]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence. Indications for ACE inhibitors in the early treatment of acute myocardial infarction: systematic overview of individual data from 100,000 patients in randomized trials. ACE Inhibitor Myocardial Infarction Collaborative Group. Circulation. 1998 Jun 9:97(22):2202-12 [PubMed PMID: 9631869]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHeart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators, Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, Bosch J, Davies R, Dagenais G. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The New England journal of medicine. 2000 Jan 20:342(3):145-53 [PubMed PMID: 10639539]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCowie MR, Fisher M. SGLT2 inhibitors: mechanisms of cardiovascular benefit beyond glycaemic control. Nature reviews. Cardiology. 2020 Dec:17(12):761-772. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0406-8. Epub 2020 Jul 14 [PubMed PMID: 32665641]

Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, Mosenzon O, Kato ET, Cahn A, Silverman MG, Zelniker TA, Kuder JF, Murphy SA, Bhatt DL, Leiter LA, McGuire DK, Wilding JPH, Ruff CT, Gause-Nilsson IAM, Fredriksson M, Johansson PA, Langkilde AM, Sabatine MS, DECLARE–TIMI 58 Investigators. Dapagliflozin and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. The New England journal of medicine. 2019 Jan 24:380(4):347-357. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812389. Epub 2018 Nov 10 [PubMed PMID: 30415602]

Nadir M, Malik J. Should Men Also Fear Strong Positive Emotions? JACC. Heart failure. 2022 Aug:10(8):601. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2022.05.012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35902166]

Kubzansky LD, Kawachi I. Going to the heart of the matter: do negative emotions cause coronary heart disease? Journal of psychosomatic research. 2000 Apr-May:48(4-5):323-37 [PubMed PMID: 10880655]

Beltrame JF, Crea F, Kaski JC, Ogawa H, Ong P, Sechtem U, Shimokawa H, Bairey Merz CN, Coronary Vasomotion Disorders International Study Group (COVADIS). International standardization of diagnostic criteria for vasospastic angina. European heart journal. 2017 Sep 1:38(33):2565-2568. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv351. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26245334]

Kimura K, Kimura T, Ishihara M, Nakagawa Y, Nakao K, Miyauchi K, Sakamoto T, Tsujita K, Hagiwara N, Miyazaki S, Ako J, Arai H, Ishii H, Origuchi H, Shimizu W, Takemura H, Tahara Y, Morino Y, Iino K, Itoh T, Iwanaga Y, Uchida K, Endo H, Kongoji K, Sakamoto K, Shiomi H, Shimohama T, Suzuki A, Takahashi J, Takeuchi I, Tanaka A, Tamura T, Nakashima T, Noguchi T, Fukamachi D, Mizuno T, Yamaguchi J, Yodogawa K, Kosuge M, Kohsaka S, Yoshino H, Yasuda S, Shimokawa H, Hirayama A, Akasaka T, Haze K, Ogawa H, Tsutsui H, Yamazaki T, Japanese Circulation Society Joint Working Group. JCS 2018 Guideline on Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Coronary Syndrome. Circulation journal : official journal of the Japanese Circulation Society. 2019 Apr 25:83(5):1085-1196. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-19-0133. Epub 2019 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 30930428]

Hayes SN, Kim ESH, Saw J, Adlam D, Arslanian-Engoren C, Economy KE, Ganesh SK, Gulati R, Lindsay ME, Mieres JH, Naderi S, Shah S, Thaler DE, Tweet MS, Wood MJ, American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Genomic and Precision Medicine; and Stroke Council. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: Current State of the Science: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018 May 8:137(19):e523-e557. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000564. Epub 2018 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 29472380]

Solinas E, Alabrese R, Cattabiani MA, Grassi F, Pelà GM, Benatti G, Tadonio I, Toselli M, Ardissino D, Vignali L. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: an Italian single centre experience. Journal of cardiovascular medicine (Hagerstown, Md.). 2022 Feb 1:23(2):141-148. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000001256. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34570037]

Morrow DA, Antman EM, Charlesworth A, Cairns R, Murphy SA, de Lemos JA, Giugliano RP, McCabe CH, Braunwald E. TIMI risk score for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: A convenient, bedside, clinical score for risk assessment at presentation: An intravenous nPA for treatment of infarcting myocardium early II trial substudy. Circulation. 2000 Oct 24:102(17):2031-7 [PubMed PMID: 11044416]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceScruth EA, Cheng E, Worrall-Carter L. Risk score comparison of outcomes in patients presenting with ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. European journal of cardiovascular nursing. 2013 Aug:12(4):330-6. doi: 10.1177/1474515112449412. Epub 2012 Jun 13 [PubMed PMID: 22694809]

Kutty RS, Jones N, Moorjani N. Mechanical complications of acute myocardial infarction. Cardiology clinics. 2013 Nov:31(4):519-31, vii-viii. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2013.07.004. Epub 2013 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 24188218]

McManus DD, Gore J, Yarzebski J, Spencer F, Lessard D, Goldberg RJ. Recent trends in the incidence, treatment, and outcomes of patients with STEMI and NSTEMI. The American journal of medicine. 2011 Jan:124(1):40-7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.07.023. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21187184]

Jernberg T, Johanson P, Held C, Svennblad B, Lindbäck J, Wallentin L, SWEDEHEART/RIKS-HIA. Association between adoption of evidence-based treatment and survival for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2011 Apr 27:305(16):1677-84. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.522. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21521849]

Rosamond WD, Chambless LE, Heiss G, Mosley TH, Coresh J, Whitsel E, Wagenknecht L, Ni H, Folsom AR. Twenty-two-year trends in incidence of myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease mortality, and case fatality in 4 US communities, 1987-2008. Circulation. 2012 Apr 17:125(15):1848-57. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.047480. Epub 2012 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 22420957]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBatts KP, Ackermann DM, Edwards WD. Postinfarction rupture of the left ventricular free wall: clinicopathologic correlates in 100 consecutive autopsy cases. Human pathology. 1990 May:21(5):530-5 [PubMed PMID: 2338333]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYip HK, Wu CJ, Chang HW, Wang CP, Cheng CI, Chua S, Chen MC. Cardiac rupture complicating acute myocardial infarction in the direct percutaneous coronary intervention reperfusion era. Chest. 2003 Aug:124(2):565-71 [PubMed PMID: 12907544]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFigueras J, Alcalde O, Barrabés JA, Serra V, Alguersuari J, Cortadellas J, Lidón RM. Changes in hospital mortality rates in 425 patients with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction and cardiac rupture over a 30-year period. Circulation. 2008 Dec 16:118(25):2783-9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.776690. Epub 2008 Dec 8 [PubMed PMID: 19064683]

Crenshaw BS, Granger CB, Birnbaum Y, Pieper KS, Morris DC, Kleiman NS, Vahanian A, Califf RM, Topol EJ. Risk factors, angiographic patterns, and outcomes in patients with ventricular septal defect complicating acute myocardial infarction. GUSTO-I (Global Utilization of Streptokinase and TPA for Occluded Coronary Arteries) Trial Investigators. Circulation. 2000 Jan 4-11:101(1):27-32 [PubMed PMID: 10618300]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTcheng JE, Jackman JD Jr, Nelson CL, Gardner LH, Smith LR, Rankin JS, Califf RM, Stack RS. Outcome of patients sustaining acute ischemic mitral regurgitation during myocardial infarction. Annals of internal medicine. 1992 Jul 1:117(1):18-24 [PubMed PMID: 1596043]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMalik J, Zaidi SMJ, Rana AS, Haider A, Tahir S. Post-cardiac injury syndrome: An evidence-based approach to diagnosis and treatment. American heart journal plus : cardiology research and practice. 2021 Dec:12():100068. doi: 10.1016/j.ahjo.2021.100068. Epub 2021 Nov 19 [PubMed PMID: 38559602]

Bradley EH, Nallamothu BK, Herrin J, Ting HH, Stern AF, Nembhard IM, Yuan CT, Green JC, Kline-Rogers E, Wang Y, Curtis JP, Webster TR, Masoudi FA, Fonarow GC, Brush JE Jr, Krumholz HM. National efforts to improve door-to-balloon time results from the Door-to-Balloon Alliance. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2009 Dec 15:54(25):2423-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20082933]

Krumholz HM, Herrin J, Miller LE, Drye EE, Ling SM, Han LF, Rapp MT, Bradley EH, Nallamothu BK, Nsa W, Bratzler DW, Curtis JP. Improvements in door-to-balloon time in the United States, 2005 to 2010. Circulation. 2011 Aug 30:124(9):1038-45. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.044107. Epub 2011 Aug 22 [PubMed PMID: 21859971]