Introduction

Skin grafting is a surgical procedure used to treat wounds that cannot heal independently. The procedure involves using materials to cover full- or partial-thickness wounds. These nonhealing wounds can result from burns, trauma, systemic diseases, and surgeries. Grafts used in skin grafting can be sourced from autologous tissue, a cadaver or animal, or engineered products derived from acellular components. Providing coverage for nonhealing wounds reduces infection, regulates temperature and fluid loss, and improves function and cosmesis. A split-thickness skin graft harvests the epidermis and part of the dermis from a donor site and transfers the skin to an open wound, whereas a full-thickness graft uses the entire dermis.[1][2]

Unlike flaps, skin grafts lack blood supply and depend on the wound bed for neovascularization. Traditionally, a split-thickness graft is harvested from autologous tissue at a donor site, but it can also be obtained from allografts or xenografts in various thicknesses. The lateral thigh is a common donor site, as it is accessible, has a large surface area, and heals quickly without significant complication. The trunk also serves as a common donor site. Graft thickness is divided into thin (0.15-0.3 mm), intermediate (0.3-0.45 mm), and thick (0.45-0.6 mm).[3] Because split-thickness skin graft donor sites retain portions of the dermis, including dermal appendages that retain multipotent stem cells, they can reepithelialize within 2 to 3 weeks and can be reused. This characteristic is particularly beneficial for treating large wounds with limited donor sites.[4]

An autologous skin graft is selected based on characteristics that influence contraction, capacity for successful neovascularization, donor site availability, graft durability, and suitability for the anatomic site of the wound. Split-thickness grafts are typically harvested with a dermatome, but a scalpel is used occasionally. The harvested graft can be expanded by meshing to increase surface area or left intact. Meshing provides space for fluid to drain to minimize hematoma and seroma formation. However, meshed grafts are more fragile and require a longer time for epithelization. In contrast, unmeshed grafts are more durable and pliable, provide better cosmesis, and heal faster compared to meshed grafts. In addition, unmeshed grafts may produce better nerve regeneration compared to meshed grafts.[5]

The characteristics of the wound and donor site, including wound type, thickness, and anatomic location, are crucial when harvesting and placing a skin graft. For all skin grafts, the vascularity of the donor site and absence of infection in the recipient site improve graft take, whereas proper preparation of the wound bed is essential for successful grafting. Thicker grafts require a more vascular wound bed for adequate diffusion of growth factors. Thick grafts are not ideal for chronic wounds but are a good choice in those areas subject to significant mechanical stress, such as the palms, soles, and joints. All skin grafts contract immediately upon harvesting due to the recoil of elastin fibers, and this contraction continues over time through the activity of myofibroblasts. Primary contracture is greatest in full-thickness, whereas secondary contracture is more pronounced in split-thickness grafts. Therefore, aesthetically sensitive areas around the eyelids, face, and mouth should be grafted with full-thickness skin. Grafts should ideally match the recipient's skin bed in color and properties as closely as possible. Split-thickness grafts exhibit greater pigmentation changes compared to full-thickness specimens. Meshed grafts exhibit altered texture compared to the surrounding skin, are more susceptible to trauma, and provide diminished sensory innervation.[6][7][8]

Split-thickness grafting, traditionally performed using autologous skin, now includes many hybrid and synthetic elements. Products commercially available and undergoing trials include cellular, acellular, and matrix-like products. Newer technology includes cultured epidermal autografts, a form of autologous engineering where a patient's cells are expanded in a lab and transferred to the wound. Allogenic matrices include substances derived from neonatal fibroblast harvested from the amnion, chorion, placenta, umbilical cord, and foreskin. The amnion/chorion membrane substance has been effectively used for diabetic ulcers. Bioprinting uses computer-aided design to develop cells and growth factors personalized to specific wounds, which could be automated to allow wider access to the technology. Dermal substitutes that improve vascularization and decrease inflammation are being evaluated for clinical utility. Composite materials, including synthetic and biological elements and acellular matrices from human and animal sources, provide a scaffolding to promote cell migration and angiogenesis. Although significant advances are revolutionizing skin grafting, the creation of a complete skin substitute with all appendages has not yet been achieved.[5][9]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Split-thickness skin grafts contain the epidermis and a portion of the dermis. The epidermis is the outermost layer of skin, comprised primarily of keratinocytes. This layer is thin and semitransparent, which provides a significant barrier function. The epidermis also includes melanocytes, Langerhans cells, Merkel cells, and nerve endings. Adnexal structures, including hair follicles, sweat glands, and sebaceous glands, are epidermal derivatives that integrate into the dermis. The dermis is the fibrous layer below the epidermis composed of collagen, glycosaminoglycans, and elastin. The upper portion of the dermis, the papillary dermis, contains blood vessels and nerves that provide nutrients to the epidermis through diffusion. The intercalating surface between the epidermis and papillary dermis creates stability between the two layers. The deeper portion of the dermis, the reticular dermis, contains robust collagen fibers. The dermis provides strength and stability to split-thickness skin grafts. Stem cells from hair follicles promote reepithelialization of skin graft donor sites.

Skin grafts must depend on the underlying wound bed for nutrients and blood supply. In a healthy, well-vascularized wound, first, the graft passively absorbs oxygen and nutrients in a process called imbibition. During this phase, the graft remains relatively ischemic as neovascularization occurs. Split-thickness skin grafts can tolerate up to 4 days of ischemia.[10][11][12] At the 48-hour mark, a connection is formed between capillary networks on the underside of the graft and vascularized vessels within the wound through a process called inosculation, resulting in visible graft coloration.[13] Further neovascularization occurs as endothelial cells migrate from the wound onto the basal lamina structure of the graft.[14][15][16][17] In meshed grafts, spaces between the skin heal through epithelialization originating from the skin bridge. The greater the meshed ratio, the larger the spaces between the skin bridges, requiring more epithelialization to fill the spaces.[18]

Skin grafts are secured with sutures or staples and bolstered for several days to allow the skin graft to undergo these steps, ensuring the best graft take. Split-thickness skin grafts are typically adherent after 5 to 7 days. Once the graft has integrated into the wound bed, it undergoes a maturation process that takes over 1 year to complete. Skin graft maturation can last up to several years in burn patients. The maturation process includes changes in pigmentation, flattening, and softening. Even after maturation, meshed split-thickness skin grafts may maintain a cobblestone appearance. In diabetic wounds, factors such as neuropathy, impaired microcirculation, hyperglycemia, and endothelial dysfunction impair wound healing, altering the healing timeline and the local biological environment.[19]

Indications

Open wounds that do not heal primarily due to their size, have failed to heal, or have reopened may be suitable candidates for a skin graft. Split-thickness skin grafts are indicated for larger wounds caused by trauma, burns, or surgery that do not cross joints and are not in locations of high cosmetic importance. Split-thickness grafts are used to cover chronic wounds and mucosal defects. For autologous grafts, a viable donor site is required, and the wound bed should have good vascularity and be free from contamination. Partial- and full-thickness wounds with sufficient blood supply can be grafted, including wounds involving muscle, tendon, cartilage, and bone with intact sheaths. A split-thickness graft may even be applied over vascularized biological dressings.[20]

Contraindications

Absolute contraindications to a skin graft include infected wounds, active bleeding, and wounds secondary to unresolved malignancy. Wounds with exposed bone, tendon, nerve, or blood vessel without a vascular layer are unlikely to heal. Relative contraindications include wounds over joints or areas where contraction reduces mobility or aesthetics and irradiated wounds. Patient factors such as tobacco use, anti-coagulant and chronic steroid use, bleeding disorders, or malnutrition should be considered.[21][22][23]

Equipment

The skin graft is most frequently harvested using a pneumatic or electric dermatome, which can be adjusted to achieve the desired thickness. A standard thickness for an intermediate graft is 0.015 to 0.018 inches. Blade guards are used to obtain the graft width, often 1 to 4 inches. The graft may also be harvested using a regular surgical scalpel or specialized blade.

If desired, the graft is meshed. A meshing device perforates the graft at regular intervals in preset ratios. Commonly used ratios include 3/8:1, 1:1, 2:1, 3:1, and 6:1. The graft is introduced into the mesher and moved through the machine using a manual crank.

Mineral oil is applied to the donor site and the dermatome blade to alleviate friction. Local, regional, or general anesthesia is administered as needed. After harvesting, a solution of 1:1000 epinephrine in 500 mL of 0.9% normal saline is applied to the donor site for hemostasis. Additional supplies include tissue forceps, gauze, and electrocautery. Absorbable sutures or staples are used to secure the graft to the wound. The use of fibrin glue has also been reported.

Dressings consist of petroleum-infused gauze, cotton balls, and non-absorbable sutures. Bulky gauze may be placed over the bolster. A negative pressure wound vacuum is also a common graft dressing. The donor site may be covered with a petroleum-based dressing or an anti-microbial foam dressing, gauze, and an overlying wrap.[24][25][26]

Personnel

Split-thickness skin grafts are performed by a surgical team consisting of a surgeon and an assistant. The surgeon harvests the graft and secures it to the wound bed, whereas the assistant manages equipment, positioning, and graft handling. This collaboration is essential to achieving successful outcomes and minimizing risks during the procedure.

Preparation

A crucial step in the preoperative process is obtaining informed consent from the patient. The surgeon should explain the procedures, outline possible complications, discuss the healing process, and provide detailed postoperative instructions. Donor and graft sites are clearly marked by the operating surgeon to ensure accuracy.[27]

A critical component of skin grafting is preparing the wound for the graft. The wound must be free of necrosis, purulence, and exudate. Debridement of the wound bed can be accomplished sharply with a scalpel to remove any devitalized tissue, mechanically with a curette, dermatome, or hydrosurgery device until the wound bed exhibits healthy bleeding tissue at the base.[27][28][27]

The donor site is selected based on the amount of skin graft needed, the location and features of the wound, surgical positioning of the patient, ease of donor site harvest, and aesthetics. Broad, flat regions such as the anterolateral thighs, back, trunk, lateral arm or forearm, and lateral lower leg are viable sites to harvest using a mechanical dermatome due to their firm surfaces against which the dermatome operator can push. The thighs and back provide a large surface area. The patient is positioned to allow for access to donor and graft sites.[27][29]

Technique or Treatment

The technique for harvesting a split-thickness skin graft with a dermatome is described below.

Preparation of Wound Bed and Split-thickness Skin Graft Harvest

- Debride the recipient bed and wound edges with a scalpel, curette, or irrigation to healthy bleeding tissue.

- Measure the wound.

- Connect the dermatome to power and water if pneumatic.

- Apply a fresh blade to the dermatome and select the desired guard plate width (1-4 inches). Select the graft thickness by adjusting the dial on the side of the dermatome.

- Calculate the desired graft size and mark the donor site with a surgical marker.

- Apply mineral oil to the dermatome and donor site to minimize friction.

- With the help of an assistant, apply traction to the skin beyond the designated borders of the graft to create an even surface.

- Hold the running dermatome at a 30° angle to the skin. Apply smooth downward and forward pressure as skin contact is made. Advance the dermatome steadily until the desired length is reached.

- Apply gentle traction to the graft to prevent folding.

- Tilt the dermatome up and lift off the skin to detach the graft. The graft may also be cut with a scalpel after the dermatome is shut off.

- Pull the skin graft from the dermatome using tissue forceps.

- Place the skin graft in normal saline until it is ready for use.

- Apply an epinephrine-soaked gauze to the donor site for hemostasis.

Meshing and Securing the Graft

- Mesh the graft if desired. The surgeon can fenestrate with a scalpel or a meshing device. When using a mesher, gently distract the graft for entry into and guide the graft out of the mesher.

- Transfer the graft to the wound and place it dermal side down. The dermis is shiny and whiter compared to the epidermis, and the graft often curls towards the dermal side. The skin graft fails if it is positioned upside down.

- Secure the graft to the wound with an absorbable suture, such as 4-0 gut or skin staples. Fix the graft at the corners and throughout as needed to ensure stable adherence to the wound bed.

- Apply a dressing to prevent shearing and reduce hematoma and seroma formation. Dressing options include a tie-over bolster that consists of a moisturized base with dense gauze sutured over the wound or a negative pressure wound vacuum. The choice of dressing is based on the site of the wound and institutional practices.

- Cover the donor site with a moist, occlusive dressing.[27][30][31]

Notes

Complications

Split-thickness skin grafts have a reported success rate of 70% to 90%.[21][34][21][35][36] Fluid accumulation between the skin graft and wound bed jeopardizes the graft and can result in seroma, hematoma, and infection. Shear also disrupts skin graft healing. Individuals with thinner skin, those with significant comorbidities, and children may not have sufficient or durable skin for grafting. Donor sites exhibit delayed healing in individuals with diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, and immunocompromise.[5] Aging skin is more susceptible to damage and has less perfusion. Contraction and scar may impact function and produce suboptimal cosmesis.[37] Unmeshed grafts require more surveillance, may lead to more complications, and require more revisions.[5]

Clinical Significance

Split-thickness skin grafts adhere to the recipient wound bed within 5 to 7 days after placement. During this period, dressings are left undisturbed to minimize shear. At initial postoperative inspection, the graft should be vascularized. For the next 2 weeks, dressing changes are performed daily, consisting of petroleum-infused gauze, bulky gauze, an ACE wrap, or a wound vacuum-assisted closure. These changes are carried out by the patient, home nursing care, or wound clinic. By 2 to 3 weeks, the skin grafts should be adherent and epithelialized, allowing the patient to resume showering. Lotion can be applied to the skin graft to promote suppleness and healing.[38]

A recent survey of dermatologists regarding approaches to skin grafting revealed an absence of standardization of technique, and respondents noted a relative lack of training and clinical opportunity.[39] Recent studies have proposed a staged approach to grafting burn wounds, especially in areas requiring high functional status, such as the hand. The data indicate that grafting in stages allows for more comprehensive clearing of necrotic tissue and better preservation of viable tissue, reduces inflammatory reactions, and improves the survival of skin grafts. A suggested approach is to use allogenic tissue as temporary dressing followed by definitive grafting.[40] A review of methodologies for treating burns suggested that autologous-engineered skin substitutes may reduce the surface area needed for donor sites and lower mortality rates. Using temporary allografts instead of petroleum products may result in improved healing.[41]

There have been many recent innovations in wound care materials used in skin grafting. Much of their use remains anecdotal, lacking high-powered studies. Traditional dressings for split-thickness donor sites include foam, hydrocolloid, silicone, alginate, nonadherent, and absorbent acrylic. Newer therapies, including human amniotic membrane and dermal matrices, have resulted in faster healing. Autologous-engineered cells, platelet-rich plasma, and fibrin have also been shown to decrease healing time. Clinicians have observed quicker and wider epithelialization with the use of insulin within the wound bed. There are anecdotal reports of materials that have enhanced healing and decreased pain.[42] Cutting-edge technology within the regenerative field is being applied to wound care, such as the use of pluripotent stem cell–derived skin grafts in a mouse model.[43] Autologous skin cell suspension may be a viable alternative to autologous split-thickness grafts and decrease requirements for donor skin. A study found that combining autologous skin cell suspension with split-thickness skin grafting is non-inferior and reduces the need for donor skin in full-thickness wounds.[37][44] Furthermore, treating the donor site of split-thickness grafts with platelet-rich plasma, human amniotic membrane, and recombinant growth hormone can speed the healing process, alleviate pain, and decrease infection risk.[42]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The success of skin grafts requires a collaborative interprofessional team. Clear communication about the exact procedures performed, the nature of the wounds, and required dressing changes is critical for optimal clinical outcomes. Wounds require close monitoring and stewardship. Any bleeding, infection, or ischemia should be identified and reported immediately. Dressing changes require vigilance and care.

Measures such as thrombosis prophylaxis and diet are important clinical components. A physical therapy regimen is an important facet of some skin grafts, and compression garments may be necessary to prevent hypertrophic scarring. Even following discharge, a wound care specialist should monitor the graft and donor sites until the healing is complete.[45][46]

Media

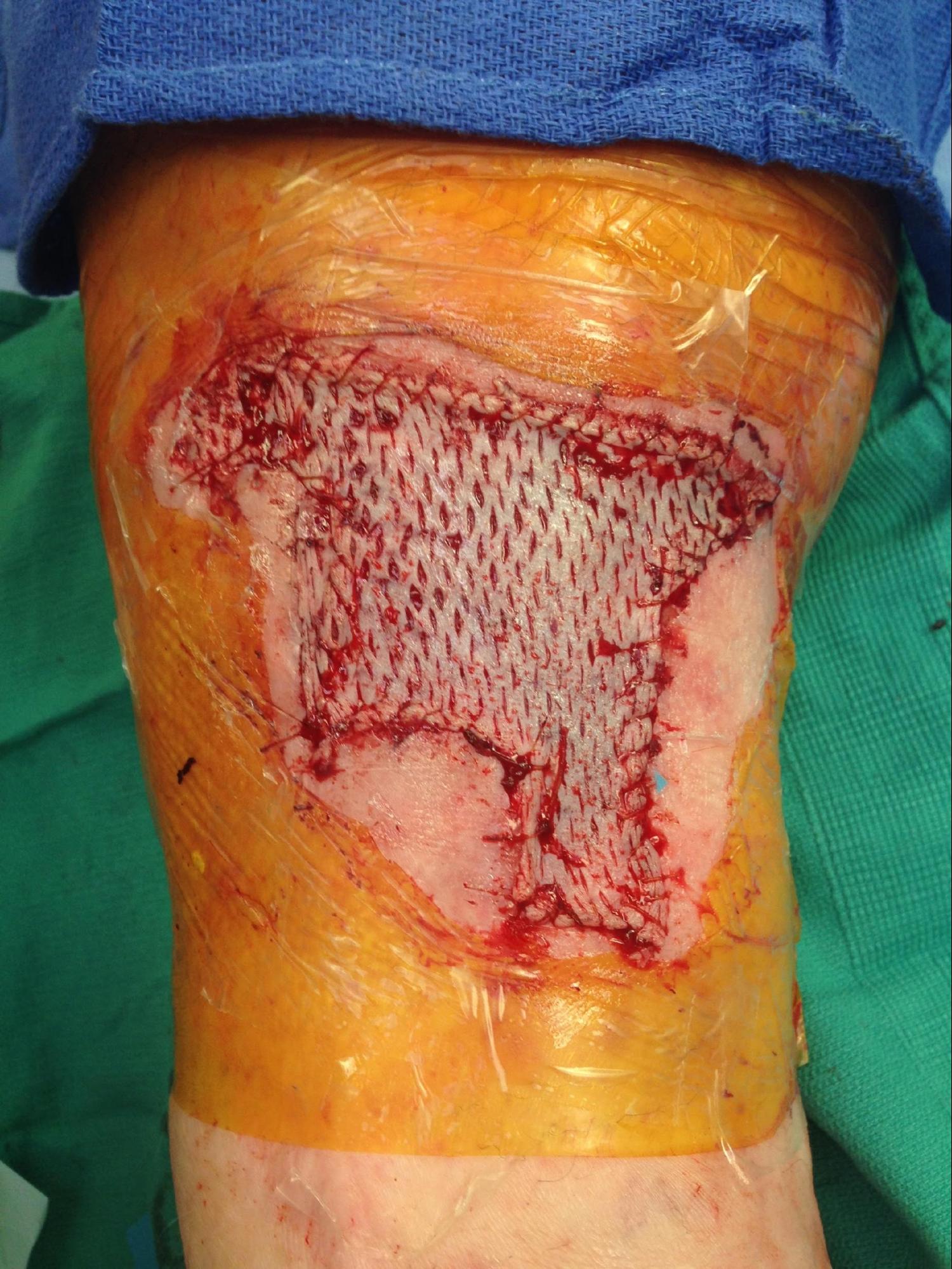

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Andreassi A, Bilenchi R, Biagioli M, D'Aniello C. Classification and pathophysiology of skin grafts. Clinics in dermatology. 2005 Jul-Aug:23(4):332-7 [PubMed PMID: 16023927]

Shimizu R, Kishi K. Skin graft. Plastic surgery international. 2012:2012():563493. doi: 10.1155/2012/563493. Epub 2012 Feb 6 [PubMed PMID: 22570780]

Johnson TM, Ratner D, Nelson BR. Soft tissue reconstruction with skin grafting. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1992 Aug:27(2 Pt 1):151-65 [PubMed PMID: 1430351]

Stephenson AJ, Griffiths RW, La Hausse-Brown TP. Patterns of contraction in human full thickness skin grafts. British journal of plastic surgery. 2000 Jul:53(5):397-402 [PubMed PMID: 10876276]

Samuel J, Gharde P, Surya D, Durge S, Gopalan V. A Comparative Review of Meshed Versus Unmeshed Grafts in Split-Thickness Skin Grafting: Clinical Implications and Outcomes. Cureus. 2024 Sep:16(9):e69606. doi: 10.7759/cureus.69606. Epub 2024 Sep 17 [PubMed PMID: 39429304]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOh SJ, Kim SG, Cho JK, Sung CM. Palmar crease release and secondary full-thickness skin grafts for contractures in primary full-thickness skin grafts during growth spurts in pediatric palmar hand burns. Journal of burn care & research : official publication of the American Burn Association. 2014 Sep-Oct:35(5):e312-6. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0000000000000056. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25144813]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBoschetti CE, Lo Giudice G, Staglianò S, Pollice A, Guida D, Magliulo R, Colella G, Chirico F, Santagata M. One-stage scalp reconstruction using single-layer dermal regeneration template and split-thickness skin graft: a case series. Oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2024 Dec:28(4):1635-1642. doi: 10.1007/s10006-024-01292-5. Epub 2024 Oct 4 [PubMed PMID: 39363141]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBhutto SA, Ali Khan FA, Sami W, Noor M, Farrrukh R, Khan S. IMPACT OF ADJUVANT FAT GRAFTING ON IMPROVED UPTAKE AND HEALING OF SPLIT THICKNESS SKIN GRAFT AT TERTIARY CARE HOSPITAL. Journal of Ayub Medical College, Abbottabad : JAMC. 2024 Apr-Jun:36(2):393-397. doi: 10.55519/JAMC-02-12934. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39609988]

Ling XW, Jiang X, Guo HL, Zhang TT. Deep burn surgery of the whole dorsum of the hand: Composite skin grafting over acellular dermal matrix versus thick split-thickness skin grafting. International wound journal. 2024 May:21(5):e14934. doi: 10.1111/iwj.14934. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38783559]

Converse JM, Uhlschmid GK, Ballantyne DL Jr. "Plasmatic circulation" in skin grafts. The phase of serum imbibition. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1969 May:43(5):495-9 [PubMed PMID: 4889411]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRudolph R, Klein L. Healing processes in skin grafts. Surgery, gynecology & obstetrics. 1973 Apr:136(4):641-54 [PubMed PMID: 4570314]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceClemmesen T. Experimental studies on the healing of free skin autografts. Danish medical bulletin. 1967 May:14():Suppl 2:1-73 [PubMed PMID: 4860071]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceConverse JM, Smahel J, Ballantyne DL Jr, Harper AD. Inosculation of vessels of skin graft and host bed: a fortuitous encounter. British journal of plastic surgery. 1975 Oct:28(4):274-82 [PubMed PMID: 1104028]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHinshaw JR, Miller ER. Histology of healing split-thickness, full-thickness autogenous skin grafts and donor sites. Archives of surgery (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1965 Oct:91(4):658-70 [PubMed PMID: 5319812]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBirch J, Brånemark PI. The vascularization of a free full thickness skin graft. I. A vital microscopic study. Scandinavian journal of plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1969:3(1):1-10 [PubMed PMID: 4903747]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSmahel J. The revascularization of a free skin autograft. Acta chirurgiae plasticae. 1967:9(1):76-7 [PubMed PMID: 4194674]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLindenblatt N, Calcagni M, Contaldo C, Menger MD, Giovanoli P, Vollmar B. A new model for studying the revascularization of skin grafts in vivo: the role of angiogenesis. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2008 Dec:122(6):1669-1680. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31818cbeb1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19050519]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYu H, Jafari M, Mujahid A, Garcia CF, Shah J, Sinha R, Huang Y, Shakiba D, Hong Y, Cheraghali D, Pryce JRS, Sandler JA, Elson EL, Sacks JM, Genin GM, Alisafaei F. Expansion limits of meshed split-thickness skin grafts. Acta biomaterialia. 2025 Jan 1:191():325-335. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2024.11.038. Epub 2024 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 39581335]

Gkotsoulias E. Split Thickness Skin Graft of the Foot and Ankle Bolstered With Negative Pressure Wound Therapy in a Diabetic Population: The Results of a Retrospective Review and Review of the Literature. Foot & ankle specialist. 2020 Oct:13(5):383-391. doi: 10.1177/1938640019863267. Epub 2019 Aug 2 [PubMed PMID: 31370687]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJanis JE, Kwon RK, Attinger CE. The new reconstructive ladder: modifications to the traditional model. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2011 Jan:127 Suppl 1():205S-212S. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318201271c. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21200292]

Thourani VH, Ingram WL, Feliciano DV. Factors affecting success of split-thickness skin grafts in the modern burn unit. The Journal of trauma. 2003 Mar:54(3):562-8 [PubMed PMID: 12634539]

Schubert HM, Brandstetter M, Ensat F, Kohlosy H, Schwabegger AH. [Split thickness skin graft for coverage of soft tissue defects]. Operative Orthopadie und Traumatologie. 2012 Sep:24(4-5):432-8. doi: 10.1007/s00064-011-0134-7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23007917]

Kern JN, Weidemann F, O'Loughlin PF, Krettek C, Gaulke R. Mid- to Long-term Outcomes After Split-thickness Skin Graft vs. Skin Extension by Multiple Incisions. In vivo (Athens, Greece). 2019 Mar-Apr:33(2):453-464. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11494. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30804125]

Han HH, Jun D, Moon SH, Kang IS, Kim MC. Fixation of split-thickness skin graft using fast-clotting fibrin glue containing undiluted high-concentration thrombin or sutures: a comparison study. SpringerPlus. 2016:5(1):1902 [PubMed PMID: 27867809]

Brown JE, Holloway SL. An evidence-based review of split-thickness skin graft donor site dressings. International wound journal. 2018 Dec:15(6):1000-1009. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12967. Epub 2018 Aug 17 [PubMed PMID: 30117716]

Ameer F, Singh AK, Kumar S. Evolution of instruments for harvest of the skin grafts. Indian journal of plastic surgery : official publication of the Association of Plastic Surgeons of India. 2013 Jan:46(1):28-35. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.113704. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23960303]

Oosthuizen B, Mole T, Martin R, Myburgh JG. Comparison of standard surgical debridement versus the VERSAJET Plus™ Hydrosurgery system in the treatment of open tibia fractures: a prospective open label randomized controlled trial. International journal of burns and trauma. 2014:4(2):53-8 [PubMed PMID: 25356370]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMalu R, Hajgude G, Rayate AS, Jaiswal K, Rao A, Nagoba B. Simple and effective approach for wound-bed preparation by topical citric acid application. Wound management & prevention. 2024 Dec:70(4):. doi: 10.25270/wmp.24014. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39788880]

Schlottmann F, Lorbeer L. Update burn surgery: overview of current multidisciplinary treatment concepts. Innovative surgical sciences. 2024 Dec:9(4):181-190. doi: 10.1515/iss-2024-0020. Epub 2024 Aug 23 [PubMed PMID: 39678122]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTaylor BC, Triplet JJ, Wells M. Split-Thickness Skin Grafting: A Primer for Orthopaedic Surgeons. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2021 Oct 15:29(20):855-861. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-01389. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34547758]

Borda LJ, Cushman CS, Chu TW. Utilization of Split-Thickness Skin Graft as a Treatment Option Following Mohs Micrographic Surgery. Cureus. 2024 Feb:16(2):e53652. doi: 10.7759/cureus.53652. Epub 2024 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 38449936]

David AP, Heaton C, Park A, Seth R, Knott PD, Markey JD. Association of Bolster Duration With Uptake Rates of Fibula Donor Site Skin Grafts. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery. 2020 Jun 1:146(6):537-542. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0160. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32297916]

Ho CY, Chou HY, Wang SH, Lan CY, Shyu VB, Chen CH, Tsai CH. A Comprehensive Analysis of Moist Versus Non-Moist Dressings for Split-Thickness Skin Graft Donor Sites: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Health science reports. 2025 Jan:8(1):e70315. doi: 10.1002/hsr2.70315. Epub 2025 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 39831076]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceShores JT, Hiersche M, Gabriel A, Gupta S. Tendon coverage using an artificial skin substitute. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2012 Nov:65(11):1544-50. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2012.05.021. Epub 2012 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 22721977]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLauerman MH, Scalea TM, Eglseder WA, Pensy R, Stein DM, Henry S. Efficacy of Wound Coverage Techniques in Extremity Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infections. The American surgeon. 2018 Nov 1:84(11):1790-1795 [PubMed PMID: 30747635]

Kirsner RS, Mata SM, Falanga V, Kerdel FA. Split-thickness skin grafting of leg ulcers. The University of Miami Department of Dermatology's experience (1990-1993). Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 1995 Aug:21(8):701-3 [PubMed PMID: 7633815]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHenry S, Mapula S, Grevious M, Foster KN, Phelan H, Shupp J, Chan R, Harrington D, Mashruwala N, Brown DA, Mir H, Singer G, Cordova A, Rae L, Chin T, Castanon L, Bell D, Hughes W, Molnar JA. Maximizing wound coverage in full-thickness skin defects: A randomized-controlled trial of autologous skin cell suspension and widely meshed autograft versus standard autografting. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2024 Jan 1:96(1):85-93. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000004120. Epub 2023 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 38098145]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBovenberg MS, Williams PE, Goldberg LH. Assessment of Pain, Healing Time, and Postoperative Complications in the Healing of Auricular Defects After Secondary Intent Healing Versus Split Thickness Skin Graft Placement. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2024 Jan 1:50(1):35-40. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000003996. Epub 2023 Nov 1 [PubMed PMID: 37910639]

Lim PN, Salence BK, Hunt WTN. Characterizing the use of full- and split-thickness skin grafts among dermatologists: an international survey. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2024 Dec 23:50(1):82-87. doi: 10.1093/ced/llae295. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39139036]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSun J, Su S, Jiao S, Li G, Zhang Z, Lin W, Zhang S. A prospective analysis of the efficacy of phase II autologous skin grafting on deep second‑degree burns on the dorsum of the hand. Experimental and therapeutic medicine. 2024 May:27(5):238. doi: 10.3892/etm.2024.12526. Epub 2024 Mar 27 [PubMed PMID: 38628661]

Aleman Paredes K, Selaya Rojas JC, Flores Valdés JR, Castillo JL, Montelongo Quevedo M, Mijangos Delgado FJ, de la Cruz Durán HA, Nolasco Mendoza CL, Nuñez Vazquez EJ. A Comparative Analysis of the Outcomes of Various Graft Types in Burn Reconstruction Over the Past 24 Years: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2024 Feb:16(2):e54277. doi: 10.7759/cureus.54277. Epub 2024 Feb 15 [PubMed PMID: 38496152]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMarkel JE, Franke JD, Woodberry KM, Fahrenkopf MP. Recent Updates on the Management of Split-thickness Skin Graft Donor Sites. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. Global open. 2024 Sep:12(9):e6174. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000006174. Epub 2024 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 39296609]

Nagano H, Mizuno N, Sato H, Mizutani E, Yanagida A, Kano M, Kasai M, Yamamoto H, Watanabe M, Suchy F, Masaki H, Nakauchi H. Skin graft with dermis and appendages generated in vivo by cell competition. Nature communications. 2024 Apr 29:15(1):3366. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-47527-7. Epub 2024 Apr 29 [PubMed PMID: 38684678]

Gould LJ, Acampora C, Borrelli M. Comparative Analysis of Autologous Skin Cell Suspension Technology and Split-Thickness Skin Grafting for Subacute Wounds in Medically Complex Patients: Propensity-Matched Cohort Study. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2025 Jan 1:240(1):34-45. doi: 10.1097/XCS.0000000000001220. Epub 2024 Dec 16 [PubMed PMID: 39431608]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLagziel T, Ramos M, Klifto KM, Seal SM, Hultman CS, Asif M. Complications With Time-to-Ambulation Following Skin Grafting for Burn Patients: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Cureus. 2021 Aug:13(8):e17214. doi: 10.7759/cureus.17214. Epub 2021 Aug 16 [PubMed PMID: 34540441]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNaz F, Javaid RH, Almas D, Yousuf B, Noor S, Awan A. COMPARISON OF NEGATIVE PRESSURE VACUUM THERAPY (NPWT) AND TIE OVER DRESSING IN HEALING SKIN GRAFTS. Journal of Ayub Medical College, Abbottabad : JAMC. 2024 Apr-Jun:36(2):355-358. doi: 10.55519/JAMC-02-12913. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39609980]