Introduction

Furrow degeneration (FD) is a unique pathology that goes by various names in the limited published literature. It is most commonly referred to as furrow degeneration; however, many articles interchangeably use senile furrow degeneration of cornea, corneal furrow degeneration, or age-related marginal corneal degeneration when referring to FD. FD is characterized by a decreasing width of the peripheral cornea between the arcus senilis and limbus. Very little focus has been made on further examining the pathophysiology and etiology of furrow degeneration, possibly due to its benign course. Unlike many other corneal degenerative diseases, furrow degeneration lacks true vascularization and inflammation as part of the pathological pathway, leading to a painless, and asymptomatic, thinning of the peripheral cornea with a low risk of perforation and little need for medical follow up. Patients with FD will not experience any changes in vision due to the circumferential thinning that occurs evenly throughout the cornea. A few case studies have been conducted that show the natural progression of the disease; however, due to its rarity, many questions remain unanswered.

This article will focus on the history and physical examination found in most patients with FD. The article will also emphasize the importance of identifying other corneal degenerations and differentiating FD from other pathologies. The specific anatomy and physiology of the cornea will not be discussed in-depth, mainly focusing on the clinical picture and medical management of FD.[1][2][3][4][5]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of FD has not been thoroughly studied, the only known risk factor is increased age.[2]

Epidemiology

Furrow degeneration is most commonly seen in elderly patients between the ages of 60-70. FD does not discriminate between men and women, equally affecting both sexes.[2]

Pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiology of furrow degeneration is largely unknown. There is a predominating theory to explain the clinical presentation of FD. To better understand the theory, one should be familiar with the basic structural anatomy of the cornea. At the center, the cornea is about 0.5 mm thick, with a gradual increase in thickness from the center to the periphery. The cornea is an aspheric optical system caused by being steeper centrally and flatter peripherally, also known as having a prolate shape. The very sophisticated anatomical structure of the cornea allows it to perform the function of optimally refracting light into the retina. The corneal shape is simple yet elegant, with any alterations of the corneal shape causing changes in vision as well as an increase in the risk of corneal perforation. The cornea consists of 3 cellular layers and 2 interface layers, each having an individual function in allowing the cornea to act as a barrier and maintain its shape, among other characteristics.[6][7][8]

The nature of FD is noninflammatory and non-progressive, subsequently leading to an asymptomatic presentation. The corneal topography in patients who have FD reveals that the entirety of the circumference of the cornea is peripherally thinned. This finding has led to the theory that patients with furrow degeneration do not have irregular astigmatism (commonly seen in other corneal degenerations) because the tensile strength caused by the thinning is evenly distributed in the cornea leading to central sphericity allowing the complex anatomical structure to keep its morphology. Thus, patients will not present with any vision loss since the cornea’s refraction function remains intact. In contrast, other corneal thinning pathologies consist of segmental thinning, which places uneven tensile strength on the cornea causing changes in the corneal shape. Given the morphology is altered in more malignant corneal degenerations, patients typically present with vision loss in the form of irregular astigmatism.[2][1]

History and Physical

Patients will be asymptomatic, lacking any changes in vision or an increased risk of perforation. A diagnosis of furrow degeneration will likely be made in a patient who is elderly, with age being the only known risk factor. No case reports or studies have been published which show any changes in vision or episodes of pain in patients with an isolated furrow degeneration diagnosis.[2][1]

Commonly, FD presents as an incidental finding on a slit-lamp examination in elderly patients. The circumferential thinning seen in FD is limited to the lucid interval located between the limbus and the corneal arcus in each eye. The epithelium is intact and lacks blood vessels. The rest of the ocular exam is normal, barring any other pathologies.[2]

Evaluation

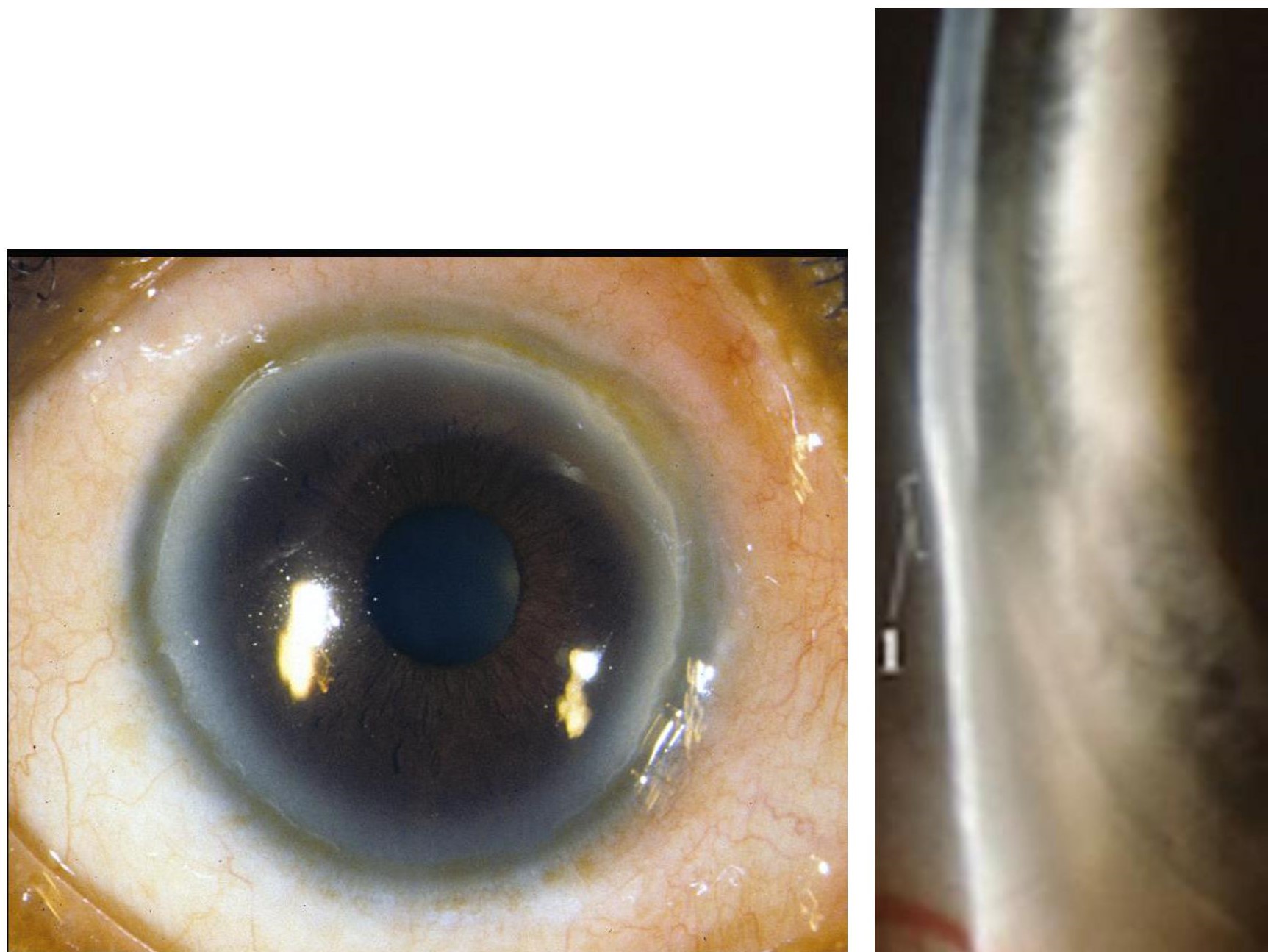

Currently, there are no laboratory or radiographic examinations that are commonly used to evaluate furrow degeneration, which is primarily a clinical diagnosis. The slit-lamp examination findings are shown in figure 1, displaying the thinning of the peripheral cornea. However, computerized topography can be used to help differentiate FD from a more serious pathology. The color-coded topographic map of FD will share similar qualities with contact-lens-induced warpage, both consisting of overall surface flattening. A patient with FD will have the unique feature of a local steepening in the periphery on the topographic map. Anterior segment optical tomography can also be used to confirm corneal thinning. Least commonly used but still effective when used to detect small changes in the corneal central surface are videokeratoscopy and computer-assisted corneal topography.[2][1][9]

Treatment / Management

Furrow degeneration is non-progressive, generally requiring no treatment. Management primarily consists of observation; however, in severe cases, lubrication or punctal occlusion can be used.[1](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

The presenting physical exam findings of furrow degeneration need to be differentiated from other possible peripheral corneal diseases to properly assess the patient’s risk for perforation or changes in vision.

Pellucid Marginal degeneration (PMD) vs. Furrow Degeneration (FD)

Similar to furrow degeneration, pellucid marginal degeneration is noninflammatory. When examined under a slit-lamp, both pathologies will be deficient in signs of scarring, vascular process, or lipid deposits. What differentiates PMD from FD on physical examination will be the location of thinning. The thinning band can be in different positions but is most commonly in inferior portions of the cornea, about 1 mm from the inferior limbus. The thinning in the inferior band results in increased curvature below the band, creating a morphological characteristic known as a “beer belly” outline on physical exam. When analyzed using corneal topography, a “crab claw” pattern on a topographic map will be displayed that is unique to PMD. The inferior thinning of the cornea mostly leads to an asymptomatic patient; however, patients can present with poor visual acuity caused by irregular astigmatism from segmental thinning. The slit-lamp examination is sufficient in diagnosing PMD as well as differentiating it from FD. Corneal topography can be used to support the diagnosis if a slit-lamp examination is inconclusive.[10][11][12]

Terrien Marginal Degeneration (TMD) vs. Furrow Degeneration (FD)

Corneal thinning in TMD occurs in 5 clinical stages, beginning with a bilateral thinning of the superior or superonasal portion of the cornea. The thinning progresses slowly, eventually leading to the thinning extending throughout the whole corneal circumference and opacification of the central cornea. On slit-lamp biomicroscopy, a stage 1 TMD will have a yellow peripheral opaque band containing deposition of lipids paired with vascularization between the opaque band and the limbus. Patients with TMD at this stage will most commonly present asymptomatically. Once patients reach stage 3, they will have slit-lamp examination findings consisting of a furrow advancing towards the central portion of the cornea. Patients begin having decreased vision, reduced corneal sensitivity, spontaneous or traumatic perforation, or corneal hydrops at this stage. Stage 4 is reached once the furrow extends the whole circumference of the peripheral cornea. In contrast, FD will have an intact epithelium and circumferential thinning in the lucid interval between the limbus and the corneal arcus in each eye without vision loss or significant findings on slit-lamp examination. The history and slit-lamp examination provide enough information to differentiate between both pathologies due to the more common presenting symptom of vision loss in TMD as well as the unique slit-lamp examination findings.[5][13]

Keratoconus vs. Furrow Degeneration (FD)

In keratoconus, the noninflammatory thinning of the corneal stroma results in the cornea taking a conical shape. Patients will often present with a worsening vision that cannot be corrected. The thinning can be seen on slit-lamp examination and is most commonly present inferiorly or inferotemporal. A conical protrusion, Fleischer ring, and fine vertical lines located on the deep stroma can also be seen on slit-lamp examination. External signs are also present, such as Munson’s sign and Rizzuti’s sign. The lower lid takes a V-shaped conformation in downgaze due to the ectatic cornea in Munson’s sign. A focused beam of light at the nasal limbus made by the lateral illumination of the cornea is known as Rizzuti’s sign. FD will not have any of the above-mentioned slit-lamp exam findings. The only feature on slit-lamp is thinning of the circumferential cornea. Finding a thinning cornea, along with any features mentioned above, should shift the differential from FD to keratoconus. A keratoscope or computer-assisted videokeratoscopes can be used to diagnose and differentiate keratoconus from FD, along with history and physical.[14]

Keratoglobus vs. Furrow Degeneration (FD)

Keratoglobus consists of a diffuse thinning of the cornea from limbus to limbus along with globular protrusion. The main presenting symptom of keratoglobus is poor vision caused by myopia with irregular astigmatism; however, there have been cases of spontaneous or traumatic corneal perforations. On slit-lamp examination, the unique finding on keratoglobus will be globular protrusion of the cornea with other corneal characteristics remaining within normal parameters. The pathology usually begins at birth and is most predominant in the periphery of the cornea. The diagnosis of keratoglobus is primarily clinical, as is differentiating it from FD. Certain investigational modalities can be used to diagnose keratoglobus, such as ultrasonic pachymetry and corneal topography, but only in cases of an inconclusive slit-lamp examination and history.[15][16][9]

Dellen vs. Furrow Degeneration (FD)

Dellen formation is caused by local corneal evaporation and dehydration derived from a break in the tear film layer. They are commonly described as saucer-like lesions on the temporal side of the cornea with clearly defined borders. The lesion is commonly secondary to an underlying ophthalmologic pathology, with minimal discomfort and usually self-resolving. Delen can be differentiated from FD by the location and shape of the lesion on slit-lamp examination. Dellen is rarely an isolated pathology. On follow-up examination, Dellen will have mostly resolved, while FD will have remained unchanged.[17][18]

Prognosis

Patients with furrow degeneration will likely remain asymptomatic. One case study showed no change in corneal thinning after a one-year follow-up while a second case study showed no worsening of the thinning after a 3-month follow-up. The non-vascular nature of the pathology, as well as the lack of any epithelial defect, places FD at low risk for perforation. Patients do not usually require extensive follow-up; most patients will be advised to simply adhere to their yearly ocular visits.[2][1]

Complications

Due to the limited research and case studies done on Furrow degeneration, no isolated complications have been reported.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients will be advised to attend their yearly ocular exams to assess progression, if any, of the corneal thinning. If a patient is to be diagnosed with FD, the physician should make clear to the patient that the pathology is benign and non-progressive, decreasing the stress and anxiety of a patient when given the diagnosis of corneal degenerative disease.

Pearls and Other Issues

Furrow degeneration is a circumferential thinning of the cornea encompassing the entire peripheral section of the cornea. The thinning does not result in any major morphological changes in the cornea’s prolate shape, subsequently leading to an asymptomatic presentation.

Patients are primarily managed through observation of worsening of thinning, without the need for an increase in the frequency of ocular eye exams or treatment.

Physicians should exclude other corneal degenerative diseases before diagnosing FD due to the different management options for the more malignant pathologies.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Furrow degeneration is a rare pathology that shares similar slit-lamp examination findings with other corneal degenerative diseases. The physician should be able to immediately identify other corneal degenerative diseases due to their more progressive malignant course and vastly different management options. Whether a physician, nurse, or technician is taking the patient’s history, they should be sure to ask about changes in vision or history of trauma to the eye to diagnose the patient properly. The physician should only make the diagnosis of furrow degeneration if the patient’s clinical picture does not fit anything else. The progressive nature of other corneal degenerations could worsen significantly if a patient is misdiagnosed with FD and left a year without being observed.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Rishi P, Shields CL, Eagle RC. Conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia with corneal furrow degeneration. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2014 Jul:62(7):809-11. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.138625. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25116776]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRumelt S, Rehany U. Computerized corneal topography of furrow corneal degeneration. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery. 1997 Jul-Aug:23(6):856-9 [PubMed PMID: 9292668]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKwitko IL, Justo DM, Putz C, Kwitko S. Intraocular lens implantation in Terrien's marginal corneal degeneration. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery. 1994 Jan:20(1):78-9 [PubMed PMID: 8133486]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGoldman KN, Kaufman HE. Atypical pterygium. A clinical feature of Terrien's marginal degeneration. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1978 Jun:96(6):1027-9 [PubMed PMID: 655940]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDing Y, Murri MS, Birdsong OC, Ronquillo Y, Moshirfar M. Terrien marginal degeneration. Survey of ophthalmology. 2019 Mar-Apr:64(2):162-174. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2018.09.004. Epub 2018 Oct 12 [PubMed PMID: 30316804]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEghrari AO, Riazuddin SA, Gottsch JD. Overview of the Cornea: Structure, Function, and Development. Progress in molecular biology and translational science. 2015:134():7-23. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2015.04.001. Epub 2015 Jun 4 [PubMed PMID: 26310146]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDelMonte DW, Kim T. Anatomy and physiology of the cornea. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery. 2011 Mar:37(3):588-98. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2010.12.037. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21333881]

Rüfer F, Schröder A, Erb C. White-to-white corneal diameter: normal values in healthy humans obtained with the Orbscan II topography system. Cornea. 2005 Apr:24(3):259-61 [PubMed PMID: 15778595]

Karabatsas CH, Cook SD. Topographic analysis in pellucid marginal corneal degeneration and keratoglobus. Eye (London, England). 1996:10 ( Pt 4)():451-5 [PubMed PMID: 8944096]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMartínez-Abad A, Piñero DP. Pellucid marginal degeneration: Detection, discrimination from other corneal ectatic disorders and progression. Contact lens & anterior eye : the journal of the British Contact Lens Association. 2019 Aug:42(4):341-349. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2018.11.010. Epub 2018 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 30473322]

Barbara A, Shehadeh-Masha'our R, Zvi F, Garzozi HJ. Management of pellucid marginal degeneration with intracorneal ring segments. Journal of refractive surgery (Thorofare, N.J. : 1995). 2005 May-Jun:21(3):296-8 [PubMed PMID: 15977889]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJinabhai A, Radhakrishnan H, O'Donnell C. Pellucid corneal marginal degeneration: A review. Contact lens & anterior eye : the journal of the British Contact Lens Association. 2011 Apr:34(2):56-63. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2010.11.007. Epub 2010 Dec 23 [PubMed PMID: 21185225]

Austin P, Brown SI. Inflammatory Terrien's marginal corneal disease. American journal of ophthalmology. 1981 Aug:92(2):189-92 [PubMed PMID: 7270631]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRabinowitz YS. Keratoconus. Survey of ophthalmology. 1998 Jan-Feb:42(4):297-319 [PubMed PMID: 9493273]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWallang BS, Das S. Keratoglobus. Eye (London, England). 2013 Sep:27(9):1004-12. doi: 10.1038/eye.2013.130. Epub 2013 Jun 28 [PubMed PMID: 23807384]

Biglan AW, Brown SI, Johnson BL. Keratoglobus and blue sclera. American journal of ophthalmology. 1977 Feb:83(2):225-33 [PubMed PMID: 836664]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBaum JL, Mishima S, Boruchoff SA. On the nature of dellen. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1968 Jun:79(6):657-62 [PubMed PMID: 5652258]

Mahgoub MM, Roshdy MM, Wahba SS. Dellen formation as a complication of subconjunctival silicone oil following microincision vitrectomy. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2017:11():2215-2219. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S149531. Epub 2017 Dec 15 [PubMed PMID: 29290680]