Introduction

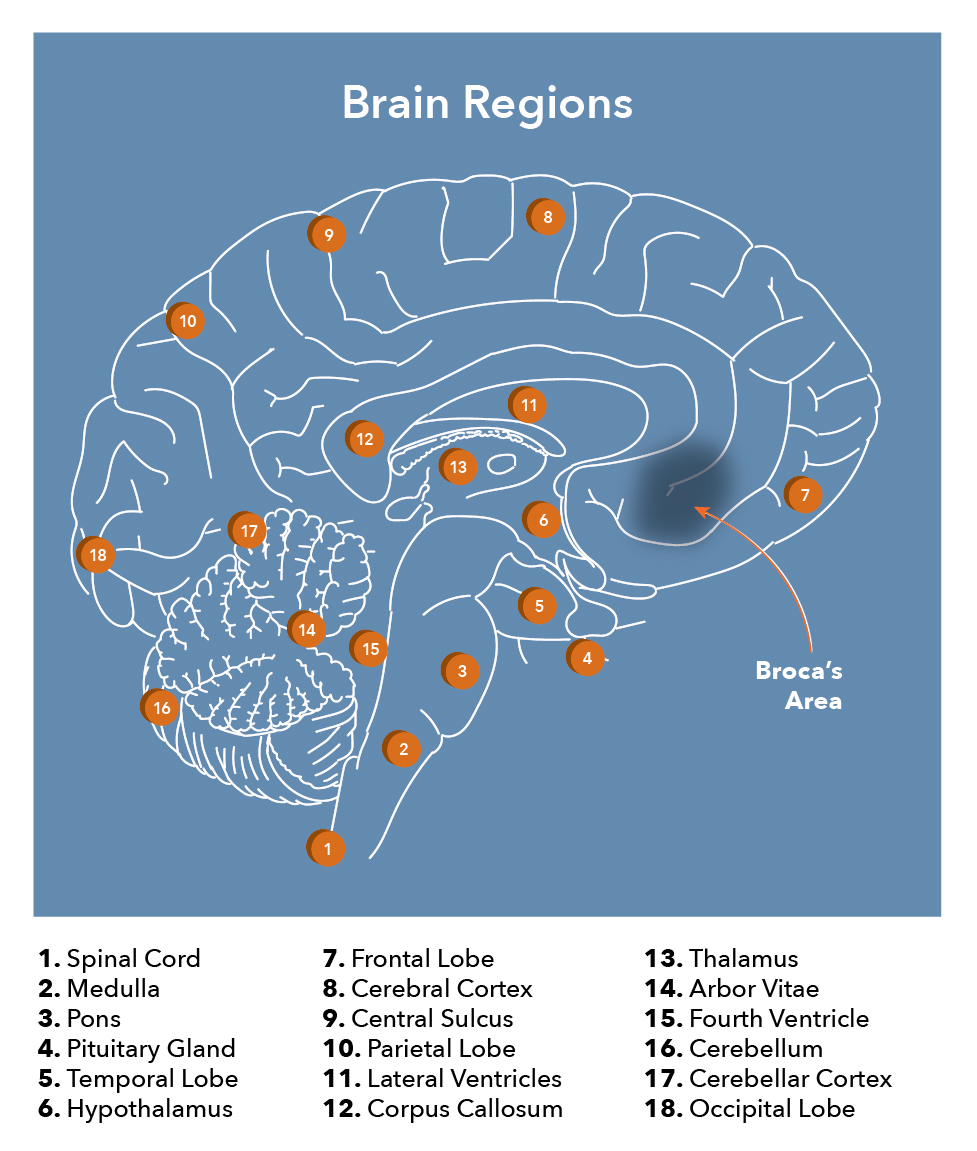

Processing and producing language is a complex process, with several structures within the brain all playing a vital role. The French physician and anatomist, Pierre Paul Broca, may have discovered the most crucial part when he identified a common region in the brain in two of his speech-impaired patients; this came to be known as the Broca (Broca's) area. This region, located in the posterior inferior frontal gyrus of the dominant hemisphere at Brodmann areas 44 (pars opercularis) and 45 (pars triangularis), is vital for language.[1] More recent research includes other areas of the frontal lobe along with the Broca area as the Broca region.[2]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The primary functions of the Broca area are both language production and comprehension. While the exact role in the production is still unclear, many believe that it directly impacts the motor movements to allow for speech. Although originally thought to only aid in speech production, lesions in the area can rarely be related to impairments in the comprehension of language. Different regions of the Broca area specialize in various aspects of comprehension. The anterior portion helps with semantics, or word meaning, while the posterior is associated with phonology, or how words sound. The Broca area is also necessary for language repetition, gesture production, sentence grammar and fluidity, and the interpretation of others' actions.[3][4][5]

Embryology

As a part of the nervous system, the Broca area originates from the embryonic ectoderm layer. It begins when a portion of the mesoderm, a transient structure known as the notochord, releases signals to the overlying ectoderm, called the neuroectoderm. This signaling causes the ectoderm to thicken into the neural plate, which will fold to create the neural tube. The neural tube further thickens to form the central nervous system, both the brain and spinal cord. The developing brain first forms three vesicles: the forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain. The forebrain, also known as the prosencephalon, further divides into the telencephalon and the diencephalon. It is from the dorsal telencephalon that the cerebral cortex arises, and that is where the Broca area will eventually come to be located.[6][7][8]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Due to its location on the lateral cortex of the cerebral hemisphere, the Broca area receives blood supply from the superior division of the middle cerebral artery. Most people are left-hemisphere dominant, which means the left middle cerebral artery (MCA) most commonly supplies the Broca area. In some cases, the callosomarginal artery serves as a collateral artery, providing a redundant, double blood supply to the area.[9]

Physiologic Variants

As previously mentioned, the Broca area is usually in the dominant cerebral hemisphere. Though not a certainty, the dominant hemisphere is commonly found to be opposite one’s handedness. A right-handed individual should have a dominant left hemisphere in most cases. Therefore, a right-handed person should theoretically vary from a left-handed in the location of their Broca area. Regardless of handedness, the Broca area is still on the left side the majority of the time.[10] While the borders may vary, the Broca area can reliably be found in the posterior inferior frontal gyrus.[1]

Clinical Significance

Insults and injury to the brain and the Broca area may lead to Broca's aphasia. Also known as expressive aphasia, it is non-fluent aphasia characterized by partially losing the ability to produce spoken and written language. Their speech will still contain important content, but they may omit articles, prepositions, and other words that only have grammatical significance. Thus, they are said to have "telegraphic speech." The aphasia can vary in severity, and in some cases, patients may only be able to speak in single-word sentences. In other words, these individuals know what they are trying to say, but they cannot say it. Patients will also lose the ability of repetition, as an intact Broca area, Wernicke's area, and arcuate fasciculus are required to repeat words or phrases. These patients do not entirely lose their ability to comprehend, but they exhibit an increased effort of speech. This is because language comprehension is primarily a function of Wernicke's area, located in the posterior superior temporal gyrus. Therefore, they are typically aware of their deficits, and Broca aphasia patients are likely to become frustrated and often develop depression. It is also essential to differentiate dysphasia from dysarthria. Those with dysarthria have problems speaking because of an inability to move mouth and tongue musculature, while expressive aphasia is more issues with word-finding.[11][12]

Broca area has correlations with the speech disorder of stuttering. This condition is also known as stammering, where speech fluidity is interrupted by unintentional prolongations and repetitions of syllables, words, and phrases. Those affected also have instances where they cannot produce sound, as demonstrated by blocks and silent pauses. When examined with fMRI, hypoactivity is visible in the Broca area with hyperactivity in motor areas. Stuttering may not be as severe as Broca's aphasia, but it can be very frustrating to those affected by it.[4]

Exceptions and variations following insult to the Broca area have occurred in some patients. For example, some patients who have suffered damage to the area, and their language expression is intact, while some patients noted to have Broca aphasia have no lesions to that region; this makes it possible that there are other areas of the brain that have a role in language expression. Damage to the Broca area can also lead to transient mutism, suggesting it may not be entirely dedicated to processing but also phonation/vocalization.

Impairments to the Broca area most frequently occur in instances of reduced blood supply to the region, with the greatest instance of this being strokes. Both ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes in the area of the middle cerebral artery can cause damage to the Broca area. Due to its large size and direct route from the internal carotid artery, the middle cerebral artery is the most regularly affected blood vessel in strokes. Therefore, Broca aphasia presents in many patients who have suffered such cerebrovascular accidents. Other lesions, such as direct trauma, tumors, or infectious masses, can be located in the area, which would have the capability to reproduce Broca aphasia.[13][14]

Media

References

Keller SS, Crow T, Foundas A, Amunts K, Roberts N. Broca's area: nomenclature, anatomy, typology and asymmetry. Brain and language. 2009 Apr:109(1):29-48. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2008.11.005. Epub 2009 Jan 19 [PubMed PMID: 19155059]

Hagoort P. Nodes and networks in the neural architecture for language: Broca's region and beyond. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2014 Oct:28():136-41. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2014.07.013. Epub 2014 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 25062474]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSkipper JI, Goldin-Meadow S, Nusbaum HC, Small SL. Speech-associated gestures, Broca's area, and the human mirror system. Brain and language. 2007 Jun:101(3):260-77 [PubMed PMID: 17533001]

Flinker A, Korzeniewska A, Shestyuk AY, Franaszczuk PJ, Dronkers NF, Knight RT, Crone NE. Redefining the role of Broca's area in speech. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015 Mar 3:112(9):2871-5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414491112. Epub 2015 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 25730850]

Brown S, Yuan Y. Broca's area is jointly activated during speech and gesture production. Neuroreport. 2018 Sep 26:29(14):1214-1216. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000001099. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30044288]

Kalia M. Brain development: anatomy, connectivity, adaptive plasticity, and toxicity. Metabolism: clinical and experimental. 2008 Oct:57 Suppl 2():S2-5. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.07.009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18803960]

Dubois J, Dehaene-Lambertz G, Kulikova S, Poupon C, Hüppi PS, Hertz-Pannier L. The early development of brain white matter: a review of imaging studies in fetuses, newborns and infants. Neuroscience. 2014 Sep 12:276():48-71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.12.044. Epub 2013 Dec 28 [PubMed PMID: 24378955]

Keyser A. Basic aspects of development and maturation of the brain: embryological contributions to neuroendocrinology. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1983:8(2):157-81 [PubMed PMID: 6353468]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTanaka M. Functional Vascular Anatomy of the Brain. Neurologia medico-chirurgica. 2017 Nov 15:57(11):584-589. doi: 10.2176/nmc.ra.2017-0030. Epub 2017 Oct 2 [PubMed PMID: 28966305]

Villar-Rodríguez E, Palomar-García MÁ, Hernández M, Adrián-Ventura J, Olcina-Sempere G, Parcet MA, Ávila C. Left-handed musicians show a higher probability of atypical cerebral dominance for language. Human brain mapping. 2020 Jun 1:41(8):2048-2058. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24929. Epub 2020 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 32034834]

Grossman M, Irwin DJ. Primary Progressive Aphasia and Stroke Aphasia. Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn.). 2018 Jun:24(3, BEHAVIORAL NEUROLOGY AND PSYCHIATRY):745-767. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000618. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29851876]

Mohr JP, Pessin MS, Finkelstein S, Funkenstein HH, Duncan GW, Davis KR. Broca aphasia: pathologic and clinical. Neurology. 1978 Apr:28(4):311-24 [PubMed PMID: 565019]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFridriksson J, Bonilha L, Rorden C. Severe Broca's aphasia without Broca's area damage. Behavioural neurology. 2007:18(4):237-8 [PubMed PMID: 18430982]

Levine RL,Dulli DA,Dixit S,Hafeez F,Khasru M, Isolated Broca's area aphasia and ischemic stroke mechanism. Journal of stroke and cerebrovascular diseases : the official journal of National Stroke Association. 2003 May-Jun [PubMed PMID: 17903916]