Introduction

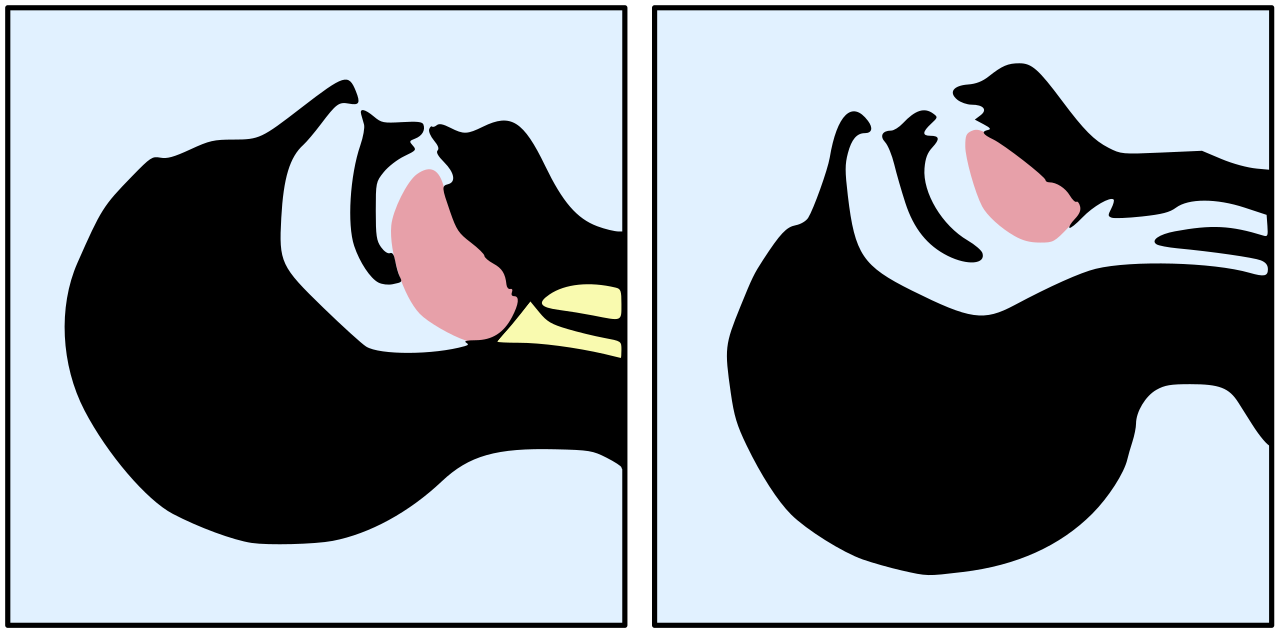

Bag valve mask ventilation is a skill of utmost important for emergency providers. It is not easy and requires practice to master as it will be utilized in emergent settings. Proper patient positioning is critical to the procedure. The tongue often falls to the back of the pharynx which can occlude the airway. The appropriate head tilt, chin lift maneuver or a jaw thrust helps to keep the airway open. The "sniffing" position is achieved with forward flexion of the neck and equilibrating the sternal notch and angle of the mandible. An oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal may be utilized to maintain an open airway. Not only does the sniffing position assist with opening the airway as needed, but it can also help visualize the glottis opening as well as the vocal cords, improving your ability for first pass success during endotracheal intubation. Many BVMs are augmented by a one-way valve or a pressure valve. They require an oxygen supply to adequately deliver oxygen to the patient.[1][2][3][4]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

A review of oropharyngeal anatomy is important to understand the implications of BVMBVM ventilation. Anatomy may cause difficulty with ventilation.

It is important to predict which patients may be difficult to ventilate. Several acronyms have been formed to help predict who will be difficult to ventilate. MOANS stands for "mask seal, obesity, age (elderly), no teeth, stiffness." BONES stands for "beard, obese, no teeth, elderly, sleep apnea/snoring." These patients may be particularly difficult to ventilate and may require the use of a supraglottic airway to improve chances of ventilation. Likewise, several studies have identified factors that are associated with difficulty ventilating patients. These include the presence of a beard, obesity, lack of teeth, snoring, older age, and limited jaw protrusion. Leaving the patient’s dentures in, if applicable, helps create a better seal for the mask. A beard or significant facial hair can make it difficult to ventilate; the use of a water-soluble lubricant can improve the ability to create a seal.

Indications

- hypercapnic respiratory failure

- hypoxic respiratory failure

- apnea

- altered mental status with the inability to protect the airway

- patients who are undergoing anesthesia for elective surgical procedures may require BVM ventilation

Contraindications

- Total upper airway obstruction

- Increased risk of aspiration after paralysis and induction

Equipment

The equipment required includes a bag valve mask, oxygen source, oxygen tubing, a PEEP valve, and simple airway adjuncts such as an oropharyngeal airway and nasopharyngeal airway.

Personnel

In general, bag valve mask ventilation only requires one provider. A second provider can help squeeze the bag while the primary provider holds the mask seal.

Preparation

An oropharyngeal airway may be inserted in order to displace the tongue forward. This prevents the occlusion of the airway when the patient is laying supine. The only true contraindication to using it is if the patient has a gag reflex. The airway can be inserted directly or rotated 90 or 180 degrees in order to facilitate placement behind the tongue.

A nasopharyngeal airway can be inserted to enable ventilation via BVM to reach the posterior pharynx in the case of a large tongue or other obstruction. It is contraindicated in the case of facial trauma where there is a concern for a facial fracture due to the possibility of it violating the intracranial space. The airway can be inserted with the bevel towards the septum, after appropriate lubrication, and rotated as needed to extend to the posterior pharynx. The use of either of these basic airway adjuncts facilitates ventilating a patient by maintaining a patent airway.

The rescuer should be positioned at the patient’s head. A good face seal must be achieved with the mask over the face, the pointed end of the mask over the nose, and the curved end below the lower lip. A one-person technique involves the "E-C seal" in which your first and second digits form a "C" over the mask with your thumb pressing down by the nasal bridge, your second digit over the bottom of the mask by the mouth, and your third through fifth digits forming an "E" and applying pressure to the mandible to hold the mask tight. There should be no gaps between the mask and the skin. You can also tilt the head backward in a “head-tilt chin lift” maneuver or can displace the jaw forward to do a “jaw-thurst” if indicated to open the airway. This often provides for easier ventilation.

In a two-person technique, someone else squeezes the bag while the rescuer uses the same E-C technique with both hands. This has been shown to deliver a higher tidal volume in simulations and also allows for a better seal to be created. One must be careful to ensure that the soft tissue of the neck is not compressed by the rescuer's fingers.

Positioning the patient can improve the ability to ventilate. Utilizing the sniffing position, with the ear to sternal notch aligned in the same plane, optimizes conditions for airflow. Utilizing a mask a size larger than expected may help create a seal, but a smaller mask is more likely to lead to a leak.[5][6][7]

Technique or Treatment

An adult BVM with oxygen supplied at a minimum of 15 liters per minute and a full reservoir can provide up to 1.5 liters of oxygen delivered per breath. Ventilating should be done with caution and only until chest rise is appreciated to reduce the risk of gastric insufflation, possibly causing vomiting and barotrauma from overdistention.

Complications

The complications include barotrauma from too much lung inflation and gastric insufflation which can lead to vomiting and aspiration.

Clinical Significance

The routine use of cricoid pressure during BVM ventilation and endotracheal intubation was initially standard practice but has never routinely been shown to improve patient-oriented outcomes. Its original purpose was to occlude the esophagus and prevent gastric regurgitation and thus aspiration. Some studies have shown it has displaced the esophagus, rather than occluding it. Others have shown that it is incompletely occluded depending on the amount of force applied. Further studies have shown it inhibits laryngeal view during intubation.[8][9][10]

BVM ventilation can be aided by the use of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) valve attached and titrated from 5 to 15 cm H2O in order to improve oxygenation prior to intubation in patients who are unable to be appropriately pre-oxygenated with standard therapy. Do not exceed a PEEP of 20 cm H2O on a BVM as this pressure can open the lower esophageal sphincter and cause gastric insufflation and vomiting.

Low pressure, low volume insufflation can help prevent gastric distention.

Some BVMs have the ability to attach a filter for pathogens. However, these devices are not foolproof, and personal protective equipment is required for every patient contact.

Likewise, the adapter for the BVM can fit an end-tidal monitor or a nebulizer reservoir. This allows additional functioning of the BVM. If the seal with the face is inadequate, this does limit the utility of these devices, as the end-tidal reading will be inaccurate and the nebulized medications may leak out.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Bag-mask ventilation is a very useful technique when encountering patients in respiratory distress. the technique is commonly used by EMS, anesthesiologist, ICU nurses, respiratory therapists, and intensivists. The technique can be life-saving and is relatively much easier than intubation. When done well, the patient can be oxygenated until an anesthesiologist can intubate the patient. an interprofessional approach will provide the best care for the patient. [Level V]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Strzelecki C, Shelton CL, Cunningham J, Dean C, Naz-Thomas S, Stocking K, Dobson A. A randomised controlled trial of bag-valve-mask teaching techniques. The clinical teacher. 2020 Feb:17(1):41-46. doi: 10.1111/tct.13008. Epub 2019 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 30811881]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCarlson JN, Wang HE. Updates in emergency airway management. Current opinion in critical care. 2018 Dec:24(6):525-530. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000552. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30239412]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKroll M, Das J, Siegler J. Can Altering Grip Technique and Bag Size Optimize Volume Delivered with Bag-Valve-Mask by Emergency Medical Service Providers? Prehospital emergency care. 2019 Mar-Apr:23(2):210-214. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2018.1489020. Epub 2018 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 30130437]

Sall FS,De Luca A,Pazart L,Pugin A,Capellier G,Khoury A, To intubate or not: ventilation is the question. A manikin-based observational study. BMJ open respiratory research. 2018; [PubMed PMID: 30116535]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCierniak M, Maksymowicz M, Borkowska N, Gaszyński T. Comparison of ventilation effectiveness of the bag valve mask and the LMA Air-Q SP in nurses during simulated CPR. Polski merkuriusz lekarski : organ Polskiego Towarzystwa Lekarskiego. 2018 May 25:44(263):223-226 [PubMed PMID: 29813039]

Delorenzo A, St Clair T, Andrew E, Bernard S, Smith K. Prehospital Rapid Sequence Intubation by Intensive Care Flight Paramedics. Prehospital emergency care. 2018 Sep-Oct:22(5):595-601. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2018.1426666. Epub 2018 Feb 6 [PubMed PMID: 29405803]

Becker HJ, Langhan ML. Can Providers Use Clinical Skills to Assess the Adequacy of Ventilation in Children During Bag-Valve Mask Ventilation? Pediatric emergency care. 2020 Dec:36(12):e695-e699. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001314. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29084068]

Costello JT,Allen PB,Levesque R, A Comparison of Ventilation Rates Between a Standard Bag-Valve-Mask and a New Design in a Prehospital Setting During Training Simulations. Journal of special operations medicine : a peer reviewed journal for SOF medical professionals. Fall 2017; [PubMed PMID: 28910470]

Lacerda RS, de Lima FCA, Bastos LP, Fardin Vinco A, Schneider FBA, Luduvico Coelho Y, Fernandes HGC, Bacalhau JMR, Bermudes IMS, da Silva CF, da Silva LP, Pezato R. Benefits of Manometer in Non-Invasive Ventilatory Support. Prehospital and disaster medicine. 2017 Dec:32(6):615-620. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X17006719. Epub 2017 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 28743318]

Pearson DA, Darrell Nelson R, Monk L, Tyson C, Jollis JG, Granger CB, Corbett C, Garvey L, Runyon MS. Comparison of team-focused CPR vs standard CPR in resuscitation from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: Results from a statewide quality improvement initiative. Resuscitation. 2016 Aug:105():165-72. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.04.008. Epub 2016 Apr 27 [PubMed PMID: 27131844]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence