Introduction

Tricuspid stenosis is a rare valvular abnormality characterized by tricuspid valve narrowing. This condition increases the pressure gradient between the right atrium and ventricle, causing systemic congestion and reduced right ventricular output. Isolated tricuspid stenosis is uncommon. This condition typically occurs along with other valvular abnormalities, most frequently mitral valve pathology, as a complication of rheumatic heart disease.[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Tricuspid stenosis is the narrowing of the tricuspid orifice that obstructs blood flow from the right atrium to the right ventricle. The right atrium hypertrophies and distends, and sequelae of right heart disease-induced heart failure develop but without right ventricular dysfunction. The right ventricle remains underfilled and small. The cause of tricuspid stenosis can be broadly classified into 3 categories: acquired, congenital, and iatrogenic.[2]

Acquired Tricuspid Stenosis

Rheumatic heart disease is the most common cause of acquired tricuspid stenosis. The condition almost always occurs in conjunction with mitral stenosis. In a series of 173 patients with rheumatic heart disease, 15 had tricuspid stenosis [3]

Large infected vegetations can cause relative stenosis.[4] Carcinoid syndrome can produce isolated tricuspid stenosis or, more commonly, mixed regurgitant and stenosed lesions.[5]

Systemic diseases that can cause tricuspid stenosis include systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APAS), known to cause nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis. Hypereosinophilic syndrome and endomyocardial fibrosis can also give rise to tricuspid stenosis.[6]

Benign tumors like atrial myxomas can produce this valvular abnormality.[7] Among metastatic tumors, renal and ovarian tumors are known to metastasize and grow into the tricuspid orifice, causing stenosis.[8]

Congenital

Congenital tricuspid stenosis is very rare, arising from tricuspid deformities due to deformed leaflets and chordae and displacement of the entire valve apparatus. Tricuspid stenosis is usually found in conjunction with other cardiac abnormalities, such as:

- Small-volume right ventricular sinus cavity

- Pulmonary atresia or severe pulmonary valvar stenosis and no ventricular septal defect

- Absent right ventricle sinus and a double-inlet single left ventricle

- Ventricular septal defect without pulmonary valvar atresia or severe stenosis

- Rhabdomyoma of ventricular septum

Other less common causes of tricuspid stenosis include congenital abnormalities such as Ebstein anomaly and metabolic or enzymatic abnormalities such as Fabry and Whipple diseases.[9][10]

Iatrogenic

The presence of permanent pacing and fusion of implantable cardioverter defibrillator leads within subvalvular structures can cause tricuspid stenosis.[11][12] Tricuspid stenosis may also occur after overzealous tricuspid valve repair for tricuspid regurgitation, eg, bioprosthetic tricuspid valve stenosis (a serious and late complication of tricuspid valve replacement).[13]

Valvular disease linked to anorectic medications, such as fenfluramine, phentermine, and methysergide, can also lead to tricuspid narrowing. Prolonged use of these drugs is connected to thickened, fibrotic, and hypomobile tricuspid leaflets, leading to varying levels of valve stenosis and regurgitation.[14][15][16] Methysergide has been associated with tricuspid stenosis since 1974.[17] Microdosing of certain psychedelic drugs can increase the risk of valvulopathy and tricuspid stenosis.[18]

Epidemiology

Tricuspid stenosis accounts for about 2.4% of all cases of organic tricuspid valve disease and is commonly seen in young women. This condition accounts for less than 1% of valvular heart diseases.[19][20] In a study of 13,289 patients with primary valvular disease, tricuspid stenosis was found in 0.3%, followed only by pulmonary stenosis in 0.04%. At least 90% of these patients had rheumatic heart disease.[21]

Pathophysiology

The primary result of tricuspid stenosis is right atrial pressure elevation and right-sided congestion. Tricuspid stenosis causes increased pressure between the right atrium and ventricle during diastole, amplified during inspiration and exercise, and reduced during expiration. Increasing severity of tricuspid stenosis leads to failure to augment cardiac output during exercise. Clinically, tricuspid stenosis results in signs and symptoms of systemic congestion.

The valves consist of an outer layer of valve endothelial cells (VECs) surrounding 3 layers of the extracellular matrix, each with a specialized function and interspersed with interstitial valve cells (VICs).[19] Genetic or acquired (eg, environmental) causes that disrupt the normal organization and composition of the extracellular matrix and communication between VECs and VICs alter valve mechanics and interfere with the valve leaflet function, culminating in valve damage.[22] Rheumatic tricuspid stenosis is characterized by diffuse fibrous thickening of the leaflets and fusion of 2 or 3 commissures. Leaflet thickening usually occurs without calcific deposits, and the anteroseptal commissure is most involved.

Tricuspid stenosis in carcinoid syndrome is caused by the deposition of fibrous plaques through vasoactive substance-mediated reactions, mainly serotonin. The deposition of endocardial plaques results in plaque distortion, leading to tricuspid stenosis and regurgitation. Methysergide and serotonin share common chemical properties. Methysergide, a synthetic ergot alkaloid, causes fibrotic thickening and structural deterioration of the tricuspid valve.[23]

SLE can lead to tricuspid stenosis. This condition may result in the formation of immune deposits and fibrous plaques, along with the development of Libman-Sacks endocarditis. The fibrous reaction can cause valve thickening and commissural fusion, while Libman-Sacks endocarditis can lead to valve obstruction.[24] Incompletely developed leaflets, shortened or malformed chordae, a small annulus, or an abnormal number or size of papillary muscles may result in congenital tricuspid stenosis.[25]

Limited data exist on the natural history of isolated tricuspid stenosis, often associated with rheumatic mitral valve disease. Like mitral stenosis, acquired tricuspid stenosis results from a chronic, slowly progressive disease process characterized by a gradual increase in stenosis severity and a slow onset of symptoms. The underlying cause influences the mortality rate associated with tricuspid stenosis.

History and Physical

History

Patients with tricuspid stenosis may present with features of systemic congestion and reduced cardiac output, frequently with accompanying valvular heart disease such as mitral stenosis. Common symptoms include exertional dyspnea, fatigue, and exertional syncope.[26][27] Patients often experience general fatigue and weakness due to low cardiac output. These symptoms may be accompanied by a loss of appetite and a history of weight loss. The patient may also describe a feeling of fast neck pulsations. Right hypochondriac pain may be due to the stretching of the Glisson capsule by the congested liver. Carcinoid tumors, if present, may manifest with skin flushing, diarrhea, palpitations, and fatigue.

Clues to the possible etiology of the condition may be obtained from a thorough history. For example, patients may report signs and symptoms of a prior rheumatic fever episode. Infants may have the condition as a prenatal diagnosis. Chronic medical conditions, long-term use of certain medications, and prior surgical procedures may all be helpful during the clinical investigation.

Physical

The lungs are clear in patients with isolated tricuspid stenosis. Pulmonary edema often occurs due to a concomitant mitral valve pathology. The precordial examination may reveal an opening snap followed by a middiastolic rumble at the left 4th intercostal space with a shorter duration and softer intensity than a mitral stenosis murmur. The murmur and opening snap intensity increase with maneuvers that boost blood flow across the tricuspid valve, such as inspiration, leg raising, amyl nitrate inhalation, squatting, or exercise. The jugular venous pressure is elevated in tricuspid stenosis. Thus, the Kussmaul sign, or failure of jugular venous pressure to fall with inspiration, may also be seen. Signs of systemic congestion include leg edema, ascites, anasarca, and congestive hepatopathy.

Evaluation

The diagnosis of tricuspid stenosis may be complicated by the subtlety of symptoms in some patients and overlapping presentations in others where it cooccurs with another cardiac pathology. Thus, diagnostic testing is usually critical to the comprehensive evaluation of this condition.

Laboratory Studies

Metabolic panels may reveal mildly elevated unconjugated bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, or aminotransferases, usually related to hepatic congestion. Arterial blood gas analysis may show respiratory alkalosis with varying degrees of compensation in patients with persistent shortness of breath.[28]

However, the laboratory findings in most cases are nonspecific and potentially influenced by the underlying cause. For example, patients with SLE may manifest with pancytopenia and antinuclear antibody positivity. Individuals with carcinoid syndrome may have elevated blood levels of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid and N-terminal pro-b-type natriuretic peptide, which are sensitive and specific predictors of carcinoid heart disease.[29]

Chest Radiograph

Isolated tricuspid stenosis may manifest with right atrial enlargement and clear lung fields. When accompanying mitral stenosis, interstitial edema or straightening of the left heart border may be seen.

Electrocardiogram

An electrocardiogram may show P-pulmonale—tall and peaked P waves—as evidence of right atrial enlargement. Tall and peaked T waves are mainly observed in leads II, III, and aVF. At least 50% of patients develop atrial fibrillation.

Jugular Venous Pulse Tracing

The jugular venous pressure is elevated with a prominent or giant A wave classically greater in height than usually perceived. The conspicuous A wave is due to contraction of the right atrium against a stenosed tricuspid valve in sinus rhythm.

If tricuspid regurgitation coexists or when the rhythm is not regular, as in atrial fibrillation and flutter, the A wave becomes undermined by a similarly elevated V wave. A slow y descent may also be seen due to delayed emptying of the right atrium into the right ventricle.[30]

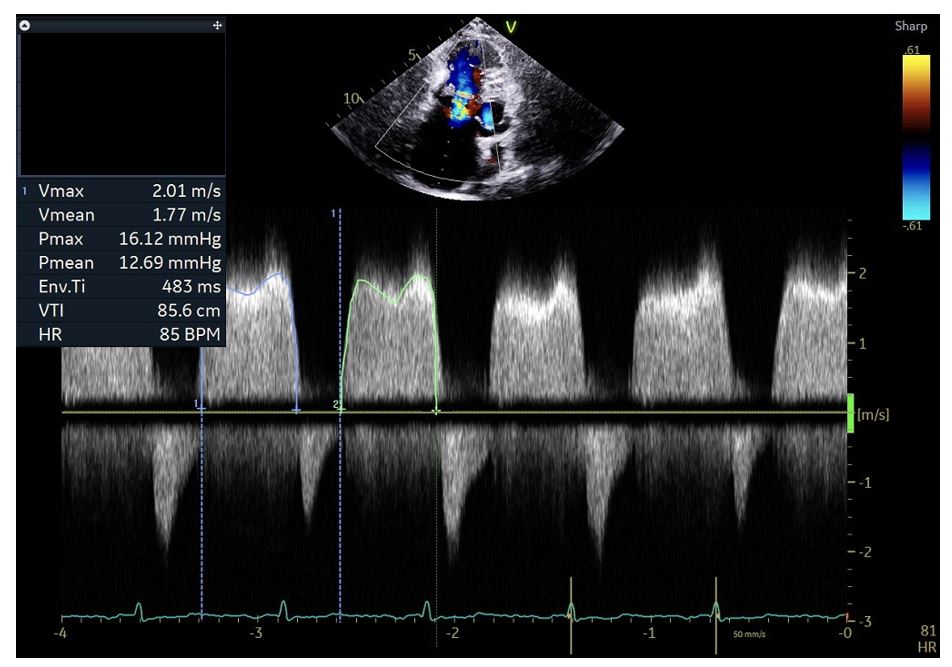

Transthoracic Echocardiogram

A transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) is performed to assess the valve area and gradients across the valve to determine the severity of tricuspid stenosis and guide management strategy (see Image. Tricuspid Stenosis on Transthoracic Echocardiography). TTE parameters help establish the severity of the disease.[31] These TTE parameters are:

- Thickening and distortion of the tricuspid valve, with or without calcification

- Commissural fusion with doming of the valve

- Valve area less than 1 cm2 signifies severe tricuspid stenosis. This parameter is calculated by dividing 190 with pressure half-time. The normal area of the tricuspid valve is 4 cm2.

- Transvalvular gradient across the tricuspid valve of more than 5 to 10 mm Hg at a heart rate of 70 beats per minute suggests severe stenosis. Gradients are affected by the patient's hemodynamic status.

- Significant tricuspid regurgitation that can potentially alter the management strategy. Surgical correction may be needed instead of percutaneous intervention.

- Pressure half-time of more than 190 msec

- Inflow-time velocity integral of more than 60 cm

- Right atrial enlargement

- Plethoric inferior vena cava

Cardiac Catheterization

Tricuspid stenosis manifests with a large right atrial A wave of 12 to 20 mm Hg and a mean diastolic gradient of 4 to 8 mm Hg across the tricuspid valve. The mean gradient across the tricuspid valve is more significant in tricuspid stenosis, as an end-diastolic gradient may be absent due to the lower filling pressures on the right side of the heart.[32] Elevated right atrial pressures with a slow fall in early diastole and a diastolic pressure gradient across the tricuspid valve are characteristic of tricuspid stenosis.

Treatment / Management

Little evidence exists regarding the management and outcomes of tricuspid stenosis. Treatment centers on addressing the underlying mechanical obstruction. Medical therapy has a limited role.

Medical

Loop diuretics may help relieve systemic and hepatic congestion in patients with severe, symptomatic tricuspid stenosis.[33] Caution is advised, however, since diuretics may excessively decrease the preload in patients with a low output state. Not every tricuspid stenosis case requires invasive intervention. SLE and APAS treatment may reduce the “coating” over the valves and chordae and, subsequently, stenosis and regurgitation.[34] Fenfluramine or methysergide withdrawal has been associated with valve normalization.[35] However, advanced cases often warrant surgical therapy besides medical management.(A1)

Intervention

Percutaneous valvotomy can be performed for patients with unacceptable surgical risk and absence of tumor, thrombus, vegetation, and insignificant or mild tricuspid regurgitation. Surgical correction (repair or replacement) is suggested for patients with low-to-moderate surgical risk or significant regurgitation. Surgical correction is recommended for patients with coexisting valvular heart diseases, such as mitral stenosis.[36]

Surgical procedures used to treat tricuspid stenosis include valvotomy and valve replacement or repair. Valvotomy is performed using 1, 2, or 3 balloons. While some stenosis may persist, the change in valve area significantly reduces the transvalvular pressure gradient and right atrial pressure.[37] Valve area generally increases by 1 to 2 cm2.[38] Bioprosthetic valve stenosis can be treated with balloon valvotomy or valve-in-valve replacement.

Tricuspid valve surgery includes repair or replacement. Surgery is usually reserved for cases with concomitant mitral valve involvement. Repair should be attempted when reasonable. Sometimes, a simple open commissurotomy suffices. When repair is not an option, valve replacement may be performed with an open approach. No differences in long-term outcomes have been established between bioprosthetic and mechanical valves.[39] However, a mechanical valve is preferred over a bioprosthetic carcinoid syndrome to avoid rapid degeneration.(A1)

Tricuspid valve surgery is indicated for symptomatic severe tricuspid stenosis accompanied by tricuspid regurgitation (eg, rheumatic and carcinoid heart diseases), as percutaneous balloon tricuspid commissurotomy may worsen regurgitation. The operative mortality for isolated tricuspid stenosis is significant and increases if performed with other valvular surgery (10% and 16%, respectively).[40](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

Diseases that can delay right atrial emptying during diastole and mimic tricuspid stenosis include but are not limited to the following:

- Cardiac mass-occupying lesions or tumors

- Thrombotic events or emboli

- Atrial myxoma/rhabdomyoma

- Congenital membranes causing supravalvular obstruction

- Tricuspid atresia

- Endocarditis with large vegetation near or around the right ventricular outflow tract

- Endomyocardial fibrosis/Loeffler endocarditis

Conditions that impair right-sided heart filling and produce similar symptoms and physical findings to those with tricuspid stenosis include the following:

- Restrictive cardiomyopathy

- Pericarditis (effusive-constrictive vs constrictive) [41]

A good clinical evaluation and judicious use of diagnostic exams can help distinguish these conditions and determine the appropriate management approach.

Staging

Clinical symptoms, hemodynamic and echocardiographic assessment, and valve anatomy determine the stage of tricuspid stenosis. The staging is as follows:

- A: Patients at risk for the disease

- B: Progressive disease but mild-to-moderate and asymptomatic

- C: Severe but asymptomatic disease

- D: Severe and symptomatic disease [33]

Stages A and B are usually asymptomatic and do not warrant intervention. Adapted from the American Heart Association executive summary on valvular heart diseases and Nishimura et al, the staging of severe tricuspid stenosis (stages C & D) is elucidated in Table 1. (See Table 1. Staging of Severe Tricuspid Stenosis.)

Table 1. Staging of Severe Tricuspid Stenosis

| Stage | Type | Anatomy | Hemodynamics | Changes | Patient Complaints |

| C & D | Severe stenosis | Leaflets: Calcified or thickened and distorted |

Pressure half-time ≥190 ms (pulmonary hypertension) Tricuspid valve area is less than or equal to 1 cm2 |

Right atrial or inferior vena cava enlargement |

Silent disease or Variable complaints depending on the degree of pulmonary hypertension and systemic venous congestion |

Prognosis

The underlying cause and the degree of ventricular dysfunction primarily determine the prognosis for tricuspid stenosis. Most patients with isolated tricuspid stenosis who undergo intervention have a good prognosis.[20] However, substantial evidence on long-term outcomes is lacking due to the rarity of this condition.

Complications

The complications of tricuspid stenosis include atrial fibrillation, heart failure, liver failure, and infective endocarditis. Early treatment and continuous monitoring can minimize the risk of these complications.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient Education

Educating patients about tricuspid stenosis is crucial for managing the condition effectively and improving their quality of life. Key points to cover include the following:

- Explain that tricuspid stenosis is a narrowing of the tricuspid valve, which impedes blood flow from the right atrium to the right ventricle, causing systemic congestion and elevated right atrial pressure.

- Patients should be aware of common symptoms, such as fatigue, exertional dyspnea, generalized weakness, exertional syncope, and signs of systemic congestion like swelling in the abdomen and legs.

- Affected individuals must be educated about potential causes, including rheumatic heart disease, carcinoid syndrome, SLE, APAS, and congenital anomalies. The importance of managing underlying conditions to prevent progression must be emphasized.

- Encourage a heart-healthy lifestyle, including a balanced diet low in sodium to reduce fluid retention, regular physical activity, and avoiding smoking and excessive alcohol consumption.

- Discuss the importance of adhering to prescribed medications and regularly monitoring their condition. Explain the role of diuretics in managing fluid overload and anticoagulants in patients with an increased thromboembolism risk.

- Educate patients on recognizing worsening symptoms, such as increased shortness of breath, severe fatigue, or sudden weight gain, and the importance of seeking prompt medical attention.

Deterrence

Preventing the progression of tricuspid stenosis and associated complications involves several strategies:

- Stress the importance of early diagnosis and treatment of conditions leading to tricuspid stenosis, such as rheumatic fever. Prompt treatment can prevent valve damage.

- Encourage regular follow-up appointments with a cardiologist to monitor the progression of the disease and adjust treatments as necessary. Echocardiograms and other diagnostic tests can help track valve function and heart health.

- Recommend vaccinations, such as influenza and pneumococcal, to prevent infections that can potentially exacerbate heart conditions.

- Advise patients to manage comorbid conditions like hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia effectively to reduce the overall burden on the heart.

- Educate about the importance of maintaining good dental hygiene and treating infections promptly, as bacterial endocarditis can worsen valvular heart disease.

Healthcare professionals can help mitigate the disease's impact and improve patient outcomes by equipping patients with knowledge about tricuspid stenosis and implementing deterrence strategies.

Pearls and Other Issues

In cases of congenital tricuspid stenosis with pulmonary valvular atresia and an intact ventricular septum, surgical interventions to enlarge the right ventricular outflow tract, such as myocardial resection, pulmonary valvotomy, partial valvectomy, and patching, may inadvertently exacerbate tricuspid stenosis. This occurrence may be due to the preexisting, small, and sometimes abnormal tricuspid valve and annulus, which may not adequately handle the increased blood flow postoperatively. Consequently, patients can develop significant tricuspid stenosis, resulting in low cardiac output and potentially leading to postoperative mortality.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of tricuspid stenosis requires interprofessional communication and coordinated care. Physicians, including cardiac surgeons, interventional cardiologists, and cardiovascular imaging specialists, must collaborate to provide accurate diagnosis and optimal treatment plans. The cardiovascular imaging specialist plays a crucial role in initial and ongoing assessments using echocardiography and other imaging modalities to evaluate valve morphology and function. Interventional cardiologists and cardiac surgeons work together to decide whether surgical or percutaneous interventions are necessary, ensuring that the chosen strategy aligns with the patient's overall health status and comorbidities. This collaboration is crucial for planning and executing complex procedures, such as valve repair or replacement, and managing potential complications.

Advanced practitioners and nurses are integral to patient education, preoperative preparation, and postoperative care, ensuring patients understand their condition, treatment options, and necessary lifestyle adjustments. These professionals monitor the patient's progress, treat symptoms, and provide emotional support, vital for recovery. Pharmacists contribute by managing anticoagulation therapy and other medications to optimize patient outcomes and minimize risks associated with polypharmacy.

Clear, consistent communication among all team members through activities that include regular interdisciplinary meetings and shared electronic health records enhances patient safety, care coordination, and overall team performance. This collaborative, patient-centered approach ensures comprehensive care that addresses the medical and emotional needs of patients with tricuspid stenosis, improving outcomes and quality of life.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Roberts WC, Ko JM. Some observations on mitral and aortic valve disease. Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center). 2008 Jul:21(3):282-99 [PubMed PMID: 18628928]

Asmarats L, Taramasso M, Rodés-Cabau J. Tricuspid valve disease: diagnosis, prognosis and management of a rapidly evolving field. Nature reviews. Cardiology. 2019 Sep:16(9):538-554. doi: 10.1038/s41569-019-0186-1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30988448]

Rashid MB, Parvin T, Ahmed CM, Islam MJ, Monwar MM, Karmoker KK, Parveen R, Shakil SS, Hasan MN. Pattern and Extent of Tricuspid Valve Involvement in Chronic Rheumatic Heart Disease. Mymensingh medical journal : MMJ. 2018 Jan:27(1):120-125 [PubMed PMID: 29459602]

Waller BF, Howard J, Fess S. Pathology of tricuspid valve stenosis and pure tricuspid regurgitation--Part I. Clinical cardiology. 1995 Feb:18(2):97-102 [PubMed PMID: 7720297]

Pellikka PA, Tajik AJ, Khandheria BK, Seward JB, Callahan JA, Pitot HC, Kvols LK. Carcinoid heart disease. Clinical and echocardiographic spectrum in 74 patients. Circulation. 1993 Apr:87(4):1188-96 [PubMed PMID: 7681733]

Mocumbi AO. Right ventricular endomyocardial fibrosis (2013 Grover Conference series). Pulmonary circulation. 2014 Sep:4(3):363-9. doi: 10.1086/676746. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25621149]

Şaşkın H, Düzyol Ç, Özcan KS, Aksoy R. Right atrial myxoma mimicking tricuspid stenosis. BMJ case reports. 2015 Aug 13:2015():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-210818. Epub 2015 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 26272962]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSeibert KA, Rettenmier CW, Waller BF, Battle WE, Levine AS, Roberts WC. Osteogenic sarcoma metastatic to the heart. The American journal of medicine. 1982 Jul:73(1):136-41 [PubMed PMID: 6953763]

McAllister HA Jr, Fenoglio JJ Jr. Cardiac involvement in Whipple's disease. Circulation. 1975 Jul:52(1):152-6 [PubMed PMID: 48435]

Khatib N, Blumenfeld Z, Bronshtein M. Early prenatal diagnosis of tricuspid stenosis. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2012 Nov:207(5):e6-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.08.030. Epub 2012 Aug 21 [PubMed PMID: 22964066]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGur AK, Odabasi D, Kunt AG, Kunt AS. Isolated tricuspid valve repair for Libman-Sacks endocarditis. Echocardiography (Mount Kisco, N.Y.). 2014 Jul:31(6):E166-8. doi: 10.1111/echo.12558. Epub 2014 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 24661289]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAl-Hijji M, Yoon Park J, El Sabbagh A, Amin M, Maleszewski JJ, Borgeson DD. The Forgotten Valve: Isolated Severe Tricuspid Valve Stenosis. Circulation. 2015 Aug 18:132(7):e123-5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016315. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26283605]

Hirata K, Tengan T, Wake M, Takahashi T, Ishimine T, Yasumoto H, Nakasu A, Mototake H. Bioprosthetic tricuspid valve stenosis: a case series. European heart journal. Case reports. 2019 Sep 1:3(3):. doi: 10.1093/ehjcr/ytz110. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31367735]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSurapaneni P,Vinales KL,Najib MQ,Chaliki HP, Valvular heart disease with the use of fenfluramine-phentermine. Texas Heart Institute journal. 2011; [PubMed PMID: 22163141]

Tomita T, Zhao Q. Autopsy findings of heart and lungs in a patient with primary pulmonary hypertension associated with use of fenfluramine and phentermine. Chest. 2002 Feb:121(2):649-52 [PubMed PMID: 11834685]

Gardin JM, Schumacher D, Constantine G, Davis KD, Leung C, Reid CL. Valvular abnormalities and cardiovascular status following exposure to dexfenfluramine or phentermine/fenfluramine. JAMA. 2000 Apr 5:283(13):1703-9 [PubMed PMID: 10755496]

Misch KA. Development of heart valve lesions during methysergide therapy. British medical journal. 1974 May 18:2(5915):365-6 [PubMed PMID: 4835843]

Rouaud A, Calder AE, Hasler G. Microdosing psychedelics and the risk of cardiac fibrosis and valvulopathy: Comparison to known cardiotoxins. Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England). 2024 Mar:38(3):217-224. doi: 10.1177/02698811231225609. Epub 2024 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 38214279]

Tao G, Kotick JD, Lincoln J. Heart valve development, maintenance, and disease: the role of endothelial cells. Current topics in developmental biology. 2012:100():203-32. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387786-4.00006-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22449845]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRoguin A, Rinkevich D, Milo S, Markiewicz W, Reisner SA. Long-term follow-up of patients with severe rheumatic tricuspid stenosis. American heart journal. 1998 Jul:136(1):103-8 [PubMed PMID: 9665226]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceManjunath CN, Srinivas P, Ravindranath KS, Dhanalakshmi C. Incidence and patterns of valvular heart disease in a tertiary care high-volume cardiac center: a single center experience. Indian heart journal. 2014 May-Jun:66(3):320-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2014.03.010. Epub 2014 Apr 14 [PubMed PMID: 24973838]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHinton RB Jr, Lincoln J, Deutsch GH, Osinska H, Manning PB, Benson DW, Yutzey KE. Extracellular matrix remodeling and organization in developing and diseased aortic valves. Circulation research. 2006 Jun 9:98(11):1431-8 [PubMed PMID: 16645142]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSmith SA, Waggoner AD, de las Fuentes L, Davila-Roman VG. Role of serotoninergic pathways in drug-induced valvular heart disease and diagnostic features by echocardiography. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography : official publication of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2009 Aug:22(8):883-9. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2009.05.002. Epub 2009 Jun 23 [PubMed PMID: 19553085]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMoaref AR, Afifi S, Rezaian S, Rezaian GR. Isolated tricuspid valve Libman-Sacks endocarditis and valvular stenosis: unusual manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography : official publication of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2010 Mar:23(3):341.e3-5. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2009.09.004. Epub 2009 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 19836204]

Shah PM, Raney AA. Tricuspid valve disease. Current problems in cardiology. 2008 Feb:33(2):47-84. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2007.10.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18222317]

Coffey S, Rayner J, Newton J, Prendergast BD. Right-sided valve disease. International journal of clinical practice. 2014 Oct:68(10):1221-6. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12485. Epub 2014 Sep 2 [PubMed PMID: 25269950]

Stapleton JF. Natural history of chronic valvular disease. Cardiovascular clinics. 1986:16(2):105-47 [PubMed PMID: 3742519]

Trombara F, Bergonti M, Toscano O, Dalla Cia A, Assanelli EM, Polvani G, Bartorelli AL. Bloody tricuspid stenosis: case report of an uncommon cause of haemoptysis. European heart journal. Case reports. 2021 Feb:5(2):ytaa537. doi: 10.1093/ehjcr/ytaa537. Epub 2021 Jan 5 [PubMed PMID: 33598616]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHassan SA, Palaskas NL, Agha AM, Iliescu C, Lopez-Mattei J, Chen C, Zheng H, Yusuf SW. Carcinoid Heart Disease: a Comprehensive Review. Current cardiology reports. 2019 Nov 19:21(11):140. doi: 10.1007/s11886-019-1207-8. Epub 2019 Nov 19 [PubMed PMID: 31745664]

Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, Applefeld MM. The Jugular Venous Pressure and Pulse Contour. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 1990:(): [PubMed PMID: 21250143]

Baumgartner H, Hung J, Bermejo J, Chambers JB, Evangelista A, Griffin BP, Iung B, Otto CM, Pellikka PA, Quiñones M, American Society of Echocardiography, European Association of Echocardiography. Echocardiographic assessment of valve stenosis: EAE/ASE recommendations for clinical practice. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography : official publication of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2009 Jan:22(1):1-23; quiz 101-2. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2008.11.029. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19130998]

Morgan JR, Forker AD, Coates JR, Myers WS. Isolated tricuspid stenosis. Circulation. 1971 Oct:44(4):729-32 [PubMed PMID: 5094152]

Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP 3rd, Guyton RA, O'Gara PT, Ruiz CE, Skubas NJ, Sorajja P, Sundt TM 3rd, Thomas JD, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014 Jun 10:63(22):e57-185. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.536. Epub 2014 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 24603191]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAdler DS. Non-functional tricuspid valve disease. Annals of cardiothoracic surgery. 2017 May:6(3):204-213. doi: 10.21037/acs.2017.04.04. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28706863]

Seghatol FF, Rigolin VH. Appetite suppressants and valvular heart disease. Current opinion in cardiology. 2002 Sep:17(5):486-92 [PubMed PMID: 12357124]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCevasco M, Shekar PS. Surgical management of tricuspid stenosis. Annals of cardiothoracic surgery. 2017 May:6(3):275-282. doi: 10.21037/acs.2017.05.14. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28706872]

Orbe LC, Sobrino N, Arcas R, Peinado R, Frutos A, Blazquez JR, Maté I, Sobrino JA. Initial outcome of percutaneous balloon valvuloplasty in rheumatic tricuspid valve stenosis. The American journal of cardiology. 1993 Feb 1:71(4):353-4 [PubMed PMID: 8427185]

Ribeiro PA, Al Zaibag M, Al Kasab S, Idris M, Halim M, Abdullah M, Shahed M. Percutaneous double balloon valvotomy for rheumatic tricuspid stenosis. The American journal of cardiology. 1988 Mar 1:61(8):660-2 [PubMed PMID: 3344697]

Kunadian B, Vijayalakshmi K, Balasubramanian S, Dunning J. Should the tricuspid valve be replaced with a mechanical or biological valve? Interactive cardiovascular and thoracic surgery. 2007 Aug:6(4):551-7 [PubMed PMID: 17669933]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLee R, Li S, Rankin JS, O'Brien SM, Gammie JS, Peterson ED, McCarthy PM, Edwards FH, Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgical Database. Fifteen-year outcome trends for valve surgery in North America. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2011 Mar:91(3):677-84; discussion p 684. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.11.009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21352979]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMcGinn JS, Zipes DP. Constrictive pericarditis causing tricuspid stenosis. Archives of internal medicine. 1972 Mar:129(3):487-90 [PubMed PMID: 4259627]