Introduction

Large bowel obstruction is a clinical emergency, often accompanied by sepsis, dehydration, and hemodynamic compromise. The obstruction can be either structural or functional. Patients with a competent ileocecal valve may have a closed-loop obstruction and be very ill upon presentation. Depending on the etiology of the obstruction, an individual may show symptoms before the acute presentation. Recognizing the signs and symptoms of large bowel obstruction is critical to provide prompt resuscitation and diagnosis to limit morbidity and improve outcomes.[1][2][3]

In some cases, an obstruction is the first clinical sign of colorectal carcinoma, particularly left-sided carcinoma, and up to 25% of colorectal carcinomas present as large bowel obstruction.[4][5] A reported 8% to 13% of colorectal cancer cases are obstructed at the time of diagnosis. A majority of emergency admissions for colorectal cancer are due to large bowel obstruction.[6] The incidence of colorectal carcinoma is increasing in young adults, often presenting as acute obstruction.[5]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The majority of large bowel obstruction arises from neoplastic, neurogenic, inflammatory, and mechanical causes within the colon. However, large bowel obstruction is also caused by extrinsic factors, such as compression from a space-occupying tumor, carcinomatosis, or fibroproliferative process within the peritoneal or retroperitoneal cavities. The most common cause of large bowel obstruction in adults is underlying colorectal cancer. A colonic malignancy may also present in the form of colonic intussusception, and other lesions, including polyps, lymphomas, lipomas, and stool impaction, may also cause intussusception. Approximately 40% of colorectal cancers cause clinical emergencies, and large bowel obstruction is the most common emergent presentation.[7][8]

Benign intrinsic causes of large bowel obstruction include inflammatory processes, foreign body or food blockages, and volvulus, particularly of the sigmoid colon. Inflammation and strictures caused by conditions such as diverticulitis, inflammatory bowel disease, anastomotic narrowing, ischemic colitis, radiation, tuberculosis, and trauma can result in obstruction.[8] Food impaction is more common in older adults, and drug packs and other foreign bodies may cause obstruction or perforation. In rare cases, the sigmoid colon can become incarcerated within a hernia, most commonly within the left inguinal area. External compression causing obstruction occurs secondary to gynecologic neoplasms, carcinomatosis, and lymphadenopathy from a variety of malignancies and inflammatory processes such as pancreatitis.[9][10]

Endometriosis can cause colonic obstruction either intrinsically or extrinsically. Retroperitoneal fibrosis is a less common cause of obstruction, characterized by inflammation and deposition of fibrotic tissue, particularly around vascular structures. This condition may result from a systemic, regional, or local response to atherosclerosis due to prior or current infection, malignancy, medication, or radiation. Rare occurrences include congenital bands, migration of medically implanted devices, such as intrauterine devices, and gallstones.[8][11][12] A case study documented an acute colonic obstruction secondary to a pharmacobezoar composed of multivitamins, exacerbated by chronic constipation, redundant sigmoid colon, and dementia.[13]

Pseudo-obstruction, a dysfunction of colonic innervation, can stem from multiple etiologies, including trauma, surgery, pregnancy, inflammation, infection, chronic metabolic or neurogenic pathologies, medications, and chronic alcohol misuse.[14]

Epidemiology

Around the turn of the 20th century, volvulus was the most commonly reported cause of large bowel obstruction. However, over the past 100 years, malignancy has become the most common underlying etiology.[15] An estimated 6% lifetime risk of malignant large bowel obstruction has been reported. Until recently, obstruction from colorectal malignancies was most common in individuals in their fifth decade of life, but the incidence of colorectal cancer in this demographic has recently diminished in most parts of the developed world. An increase in colorectal malignancy in individuals younger than 50 has been observed, most of whom have not undergone screening and present with aggressive and advanced disease in the emergency setting.[16][17]

Kwaan et al. examined 31,277 individuals admitted for large bowel obstruction between 2010 and 2015. Of those, 54% were women, 69% were White, 12% were Black, 12% were other races, the median age was 66, 20% were diagnosed with colon cancer, 15.6% with a malignancy outside the colon, 64.7% with benign conditions, including diverticulitis, ischemic colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and other causes. In this study, women with large bowel obstruction were older, had fewer comorbidities, had more malignancies outside the colon, and had more benign obstructions. Black patients tended to be younger than White patients, had more comorbidities, and had a higher likelihood of obstructing colon cancer.[18]

Among patients with colorectal cancer, obstruction represents 80% of emergencies and 20% of perforations. According to a 2017 study, the most common site for malignant obstruction was distal to the splenic flexure. Most perforations occur at the tumor site, and the remainder occur proximal to the tumor.[1] Younger individuals, men, and those with obstruction in the ascending colon have a greater likelihood of presenting for emergency treatment for colonic obstruction currently compared to previous decades.[5]

Pseudo-obstruction is more common in men older than 60, many of whom are critically ill, with a reported incidence of 0.1% of inpatient admissions in the United States. If a pseudo-obstruction progresses to ischemia or perforation, the mortality is as high as 44%.[14] In individuals diagnosed with pseudo-obstruction, the risk of cecal perforation is 15%, with a mortality of 50%. Duration of distension correlates with the risk of perforation.[19] The average age of a person with a sigmoid volvulus is 70, whereas a cecal volvulus typically occurs in individuals in their fifth decade.[14]

Pathophysiology

Large bowel obstruction in a competent ileocecal valve setting involves a segment of the colon that does not permit inflow or outflow. Over time, the segment continues to distend, exacerbated by gas-forming bacteria. The distension initially impedes venous outflow, further contributing to the dilation until arterial inflow is compromised. This process progresses from reversible to irreversible ischemia and necrosis, ultimately leading to perforation. The cecum has the largest diameter and thinnest wall and is thus at greatest risk of perforation. When the colon is obstructed and distended, its motility is disrupted, leading to bacterial overgrowth. Mucosal edema and ischemia lead to the breakdown of the mucosal barrier, resulting in bacterial translocation of the gut flora and fecalization of the small bowel, increasing the risk of bacteremia and sepsis.[1][12]

Pseudo-obstruction is attributed to excessive sympathetic stimulation within the colon due to a disruption of parasympathetic activity, further exacerbated by the direct stimulation of mechanoreceptors, resulting in decreased motility. Factors contributing to the incidence of volvulus include poor or absent peritoneal fixation of the colon, a longer or redundant colon segment, and thinning of the colonic mesentery in the setting of dysmotility secondary to causes such as chronic constipation or use of laxatives.[1][12][14][20]

History and Physical

The clinical features of large bowel obstruction depend on the etiology and the anatomical site of the obstruction. In general, patients may present with pain, abdominal distention, minimal or absent flatus or bowel movements, and nausea and vomiting. Patients with an incompetent ileocecal valve decompress their large bowel into the small bowel, eventually leading to vomiting. However, patients with a competent ileocecal valve have ongoing distension of the obstructed colon and often develop progressive right iliac fossa pain, signifying impending cecal perforation. A rectal examination may reveal a vault empty of stool, a mass, or blood.[21]

Clinical Features of Colorectal Malignancy–Associated Obstruction

Obstruction caused by underlying colorectal malignancy commonly occurs in the descending or sigmoid colon and rectum, where the diameter of the colon is smaller and the stool is more solid. Individuals may experience changes in bowel habits leading up to an obstruction, possibly an alternating pattern between diarrhea and constipation, as only liquefied content may pass through the narrowed lumen. Symptoms may be present for weeks or months before an acute presentation and may include rectal bleeding and weight loss, but an obstruction may also present abruptly. Patients may or may not have a family history of colorectal cancer.[21][22]

Clinical Features of Volvulus-Associated Obstruction

Sigmoid volvulus is common in individuals with limited mobility and a history of constipation, such as those who are bedbound and more sedentary residents of congregate care facilities. A volvulus typically presents more acutely than many other etiologies, with abdominal pain, distension, and an abrupt change in bowel habits. The examination of the abdomen reveals significant distension, tympany, and potentially guarding and rebound.[23] A cecal volvulus can present as a small bowel obstruction with variation in symptom duration. In rare cases, a volvulus may present with shock or as intermittent and chronic symptomology.[14] Individuals experiencing pseudo-obstruction may be initially indistinguishable from those with a mechanical obstruction, but pain may not feature as prominently. Individuals with pseudo-obstruction may continue to pass flatus and may experience constipation or diarrhea but also exhibit increasing abdominal distension.[14][19]

Clinical Features of Other Etiology-Associated Obstruction

Patients with obstruction due to diverticular disease may present with pain, fever, and a palpable mass, along with distension proximal to the site of obstruction. Large bowel obstruction secondary to a hernia may be associated with a reducible or irreducible mass and overlying skin changes. Sites of herniation that can cause large bowel obstruction include spigelian, lumbar, inguinal, diaphragmatic, lumbar, and intermesenteric regions. A large bowel obstruction due to endometriosis may be characterized by a history of pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, rectal pain, or pain during bowel movements. A clinical history of obstructive etiologies, such as uterine fibroids or pelvic malignancy, may include symptoms such as dysmenorrhea or irregular menstrual cycles.

Large bowel obstruction due to stool impaction is often observed in patients with a history of chronic constipation or the use of medications that reduce bowel motility. Stool impaction is more common in chronically ill or impaired individuals or those with psychiatric or medical conditions that predispose to constipation and bowel irregularity. Affected patients typically present with distension, pain, and fecal incontinence and may develop a stercol ulcer that can cause perforation. A digital rectal examination may reveal a hard stool mass in the rectum.

Retroperitoneal fibrosis can cause colonic obstruction, leading to back, flank, and abdominal pain, fevers, fatigue, and weight loss. Clinical features of colonic intussusception can be nonspecific and may include pain, nausea and vomiting, fever, bowel changes, hematochezia, and a mass identified on imaging.[8][21] A person with a perforated colon shows signs of peritonitis, with diffuse rebound and guarding, and may have physiologic distress, including tachycardia and hypotension. Pain may be sharp, radiate to the pelvis, epigastrium, or chest, and may be acute in onset with accompanied fevers, chills, nausea, and vomiting.[24]

Evaluation

Obtaining a detailed history, performing a thorough physical examination, and conducting imaging are crucial in evaluating a suspected large bowel obstruction. Laboratory tests for anemia, infection, renal function, and electrolytes are initiated to drive resuscitation and focused treatment, including infusion of contrast for imaging.[25][26][27] Leukocytosis and acidosis may indicate tissue ischemia. In addition, testing for Clostridium difficile and any electrolyte dysfunction should be conducted to help direct therapy and decision-making.[14]

Diagnostic Imaging Studies

Imaging typically begins with supine and upright or decubitus x-rays, which can reveal a dilated colon with a possible transition in the area of the obstruction and a lack of gas in the rectum or any site distal to the obstruction. Air-fluid levels may be evident in the colon. Evidence of necrosis or perforation may also be identified in an x-ray through findings such as pneumoperitoneum and gas in the bowel wall or portal venous system.[19][28][29]

A suspected obstruction identified on plain film must be distinguished from an ileus or pseudo-obstruction. Ileus may be caused by recent surgery, illness, neurologic or metabolic dysfunction, and demonstrates diffuse dilation without a transition point. Instilling a contrast enema can reliably distinguish mechanical from pseudo-obstruction. A toxic megacolon may be identified by bowel wall thickening throughout the colon. Imaging the patient in multiple postural positions can help assess colonic gas patterns. Air-fluid levels are typically absent in a pseudo-obstruction.

Determining the underlying etiology of colonic distension based on X-rays can be challenging. Therefore, computed tomography (CT) is often necessary.[19] CT can often reveal the specific etiology of large bowel obstruction, such as occult hernia, demonstrate any inflammatory or ischemic changes, and provide information regarding metastases. Intravenous contrast is useful in evaluating an obstruction; oral contrast is contraindicated. Water-soluble rectal contrast can be administered if further clarification is needed to help elucidate a volvulus or mass; a rectal enema may be used if a colonoscopy with biopsy is attempted. A colonoscopy can be performed with minimal insufflation and can provide a tissue diagnosis, including endometriosis, if the mucosa is involved.[8][19] For suspected malignancy, the entire colon should be evaluated, given the risk for synchronous lesions. CT or positron emission tomography can be used when a full colonoscopy is not feasible.[5]

A sigmoid or cecal volvulus is often evident on an x-ray. A volvulus may demonstrate the classically described coffee bean or bird beak signs. A sigmoid volvulus may extend as a U-shape into the right upper quadrant or above the transverse colon. A cecal volvulus may remain in the right lower quadrant or loop into the left upper quadrant, and the displaced appendix may be visualized in this location with the dilated cecum. Rarely, a volvulus may occur along the transverse colon or splenic flexure. A CT can localize a volvulus and identify any areas of ischemia (see Image. Cecal Volvulus). A water-soluble enema may also help delineate and occasionally reduce a volvulus.[19]

CT imaging provides a clear view of diverticular obstruction, typically revealing symmetric wall thickening and hyperemia, often accompanied by fat stranding and inflammation. Free fluid, abscesses, and fluid at the root of the mesentery may also be visible. Malignancy may be distinguished from diverticulitis by its shorter segments, asymmetric thickening, and associated lymphadenopathy. A colonic mass or benign lesion may cause an intussusception, appearing on CT as the lead point with mesenteric fat telescoping within a thickened colon, demonstrating a target sign on CT. Inflammatory bowel disease also reveals wall thickening and luminal narrowing within any strictures, whereas mucosal enhancement is present in areas of active inflammation. Fistulae and abscesses may also be present. Malignancy should always be considered in areas of inflammation. A pseudo-obstruction may demonstrate marked cecal distension extending through the transverse colon, with air apparent to the rectum.[19]

Additional Diagnostic Studies

In 2020, the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) and the European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR) published updated guidelines outlining alternatives to colonoscopy. These recommendations include using CT colonography to diagnose suspected colon malignancy, particularly when a colonoscopy cannot be performed or following an incomplete colonoscopy. Another recommended alternative to a colonoscopy is a colon capsule endoscopy.[30]

Treatment / Management

Initial Management

Before any surgical intervention, supportive therapies targeting fluid resuscitation and metabolic dysfunction correction are essential. Patients who have experienced marked cecal distension for several days are at increased risk of perforation and should be considered for some mode of decompression. Serial imaging is critical to monitor the extent of distension over time. Pneumatosis within the cecum or colon often indicates ischemia and possibly imminent perforation. Nasogastric tube insertion can help decompress the stomach in patients with a colonic obstruction and an incompetent ileocecal valve.

For patients with perforation, source control is the primary objective. A perforation proximal to the tumor typically leads to widespread fecal contamination and sepsis. In cases of sepsis, damage control measures should be initiated within six hours of resuscitation, if possible, to achieve a central venous pressure of 8 mm Hg to 12 mm Hg, a mean arterial pressure greater than 65 mm Hg, and a central venous oxygen saturation of ≥70%, which may require pharmacotherapy including norepinephrine, epinephrine, and alkalinizing agents for severe acidosis. Antibiotic therapy for obstructed but nonperforated processes should cover anaerobes and gram-negative organisms to protect against infection from translocation and, with perforation, should include broad spectrum coverage. Image-guided drainage of any associated abscess is vital for source control.[1]

Large Bowel Obstruction Interventions

Prompt intervention in patients with large bowel obstruction is crucial to reduce morbidity and mortality from progressive ischemia and perforation. Factors mandating emergent intervention include peritonitis, evidence of ischemia, sepsis, and shock. Broad options for urgent intervention include a single or staged emergency surgery versus a temporizing measure often followed by elective surgery.

When considering intervention, a distinction in treatment approach is made for left- versus right-sided obstruction.[5] Early decompression is crucial. Many left-sided obstructions can be initially treated with a self-expanding stent or tube as a bridge to surgery. Additional considerations include gross or micro-perforation, which may spread malignancies; comorbidities, such as diabetes and cirrhosis, that may cause clinical deterioration; and the increased morbidity and mortality of emergency surgery.[5]

Stenting Procedures

Emergency surgery often requires the creation of a stoma and is associated with high morbidity and mortality, including the risk of future anastomotic leaks. Bridging procedures may allow for a single-stage operation without stoma formation. The use of stenting to temporize or palliate an acute large bowel obstruction allows for clinical preparation for elective surgery and avoids increased morbidity of emergent intervention.[4] Stenting a malignant obstruction may decrease complications, operative time, and frequency of stoma formation. Stenting reduces short-term morbidity and the need for stoma in those with obstructing malignancy in the left colon and reduces postoperative complications and mortality for right-side lesions.[4] (A1)

Stenting previously was correlated with poor outcomes. The 2014 ESGE guidelines cautioned against using stenting as a bridge to surgery. However, with improved techniques and outcomes, stenting a malignant obstruction is now supported as an alternative to emergency surgery.[6] Many studies have found comparable results between stenting and emergency stoma to alleviate obstruction, but stenting is associated with shorter hospital stays and fewer permanent colostomies.[5] Self-expandable metal stents are approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in obstructions caused by malignancy; however, these stents are not approved for obstructions secondary to benign etiologies. Benign obstructions are often treated with balloon dilation or off-label use of stenting. Noncancerous obstructed segments are typically longer and more inflamed, an environment that increases the risk for stent migration, ingrowth, and perforation.[31] Additional experimental endoscopic and percutaneous interventions are used on a case-by-case basis.[8]

Stenting indications

The 2020 update from the ESGE recommends stenting as a bridge to surgery for individuals aged 70 and older with American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification III, who have potentially curable left-sided colon cancer or for palliative care. Surgery should typically follow within 5 to 10 days of stenting for malignant large bowel obstructions without perforation.[32] Pavlidis et al. recommend emergency surgery over stenting for fit patients younger than 70, using a primary anastomosis with or without a proximal stoma.[5] The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons recommends stenting for an obstructed malignancy depending on patient-specific factors, available equipment, and expertise, estimating a rate of successful stent placement between 77% and 81%. An association between stents and an increased recurrence of malignancy and synchronous tumors has been reported; therefore, interventions following stenting to include segmental resection or subtotal colectomy are also recommended.[33](A1)

Stenting methods

Stents used for large bowel obstruction may be covered or uncovered, with diameters between 10 and 25 mm and lengths between 12 and 60 mm. Uncovered metal stents are the standard treatment for obstruction secondary to malignancies, as they do not migrate as often, are associated with greater patency, and can be used for longer segments but exhibit tissue ingrowth. A covered stent is associated with higher migration but a lower incidence of obstruction. Some off-label use of covered stenting for benign disease has been reported, but no robust objective data has been found to support the practice.[5][34] Stenting can be deployed from a colonoscope under fluoroscopy following the placement of a guidewire, and many stents have markers to help with positioning. Post-stenting protocol includes a plain radiograph to assess for free air and stent placement.[35](A1)

Stenting risks

Risks of stenting include perforation and possible dissemination of malignancy. A Japanese study involving 202 patients with colonic obstruction used a low axial force self-expanding metal stent. Study markers included the technical success of stent placement and the clinical alleviation of the obstruction, which were reported to be 97.5% and 97%, respectively, with no perforations noted in this cohort.[36]

Some experts have voiced concern that stenting is associated with increased perineural invasion of malignant cells and questioned whether the observed invasion is secondary to the biology of the lesion or induced by the stenting. A study found stenting to be an independent risk factor for perineural invasion unrelated to the time interval from stenting to surgery. The study authors correlated this finding with the severity of the obstruction rather than the stenting, positing that the pathophysiology of the severe obstruction resulted in increased pressure, leading to local invasion. A meta-analysis found higher perineural and lymphatic invasion following stenting, decreasing overall survival.[37] Another meta-analysis found higher recurrence rates when stenting was used instead of an emergent stoma, with a lower 90-day mortality in the colostomy group versus those undergoing an emergent colectomy or stenting as a bridge to surgery. Higher costs in the stent group were identified, and more eventual anastomoses were found in the stoma group.[38] Current recommendations for treating a malignant obstruction following stenting include 2 cycles of chemotherapy with fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin before operative intervention to address any theoretical risk for cancer dissemination.[6] (A1)

Alternative Interventions to Stenting

In addition to stenting, other options can bridge to surgery or provide palliative treatment for colonic obstruction. One such alternative is endoscopic dilation of the obstruction. Although stenting is more effective for malignancies and post-radiation strictures, balloon dilation is indicated for anastomotic or inflammatory strictures and often requires multiple dilations. The balloon catheter is positioned over a guidewire, inflated with saline, and then deflated and removed. The balloon size must be compatible with the lumen to minimize the risk of perforation. Dilation under fluoroscopic guidance is possible when available and involves the injection of dilute contrast into saline. Successful resolution of obstruction has been reported to be 89% following 1 dilation, with recurrent obstruction noted in up to 50% of cases within 5 years of the dilation procedure.

Another alternative to stenting is decompression using a nasogastric or rectal tube, but overall, better short-term outcomes with stenting have been observed compared to decompressive tubing.[5] Studies have reported definitive resection and reconstruction following 7% to 14% of stent cases and 12% to 60% of balloon dilation cases.[35]

Surgical Procedures

Patients with malignant obstruction require surgery as a component of curative oncologic management. Surgical interventions range from a single-stage procedure intended to be curative to multiple interventions involving alleviation of the obstruction, followed by a multi-stage oncologic resection and restoration of continuity. Patients with advanced disease may undergo palliative intervention. The surgical approach differs by anatomical location and disease stage.[5] In patients with metastatic disease, a defunctioning stoma can allow for the timely start of chemotherapy.

Patients with early-stage nonmetastatic disease may undergo resection with anastomosis, followed by adjuvant therapy as necessary. A two-stage operation remains common, including an initial primary resection with a colostomy or a diverting colostomy, followed by resection or reanastomosis. In experienced hands, laparoscopy has been associated with fewer complications, increased 3-year overall survival, and disease-free survival.[39][5] A single-stage operation for a malignant obstruction, including washout, resection, and primary anastomosis, is recommended for individuals younger than 70 with an ASA score of I or II without significant comorbidities. A study involving 600 patients with right-sided malignant obstructions indicated higher complication and mortality rates in those undergoing a single-staged procedure; however, their 5-year overall and disease-free survival rates were comparable to patients who underwent a multi-stage procedure.[40] A Japanese study highlighted increased 90-day mortality in adults older than 75 who underwent primary resection for obstructed colon cancer.[41] (A1)

The World Journal of Emergency Surgery (WJES) treatment guidelines for perforated colon cancer, if the perforation is at the tumor site, recommend resection with anastomosis for a right- or left-sided process if there is no sepsis. If left-sided cancer perforates at a site proximal to the tumor, a subtotal colectomy may be required. In this setting, the recommendation is, if possible, limited resection of the terminal ileum and allowance for a distal colon remnant above peritoneal reflection to reduce the impact of diarrhea and stool incontinence. No randomized controlled studies exist that compare the creation of an anastomosis versus a diverting stoma in the perforation setting, and an overlap in the percentage of anastomotic leaks is present when comparing emergent and elective cases. The WJES supports resection with anastomosis for right-sided obstructing cancers and an internal bypass versus stenting for nonresectable tumors and palliative situations. An option for right-sided stenting includes using a self-expanding through-the-scope stent. Neoadjuvant therapy is the standard of care for locally advanced rectal cancer, and a transverse colostomy may be created in this setting. The WJES asserts that stool in the colon does not affect the rate of anastomotic dehiscence.[1]

The optimal surgical approach for malignant obstruction remains a topic of debate, both in curative and palliative settings, for elective and emergent situations. Significant discussion persists regarding single- versus two-stage procedures for left-sided obstruction. Many stomas do not get reversed, and individuals who undergo reversal are subject to possible increased morbidity and mortality, with uncertain long-term survival benefits. Age, ASA status, operative conditions, cancer stage, and surgeon experience all influence outcomes. The use of tube decompression for left-sided malignant obstruction as a bridge to surgery remains debated, suggesting that palliative stenting is preferable to a colostomy due to lower morbidity and mortality. Studies comparing colostomy to stenting found similar morbidity but shorter recovery for stenting, but stent migration and perforations increased morbidity and mortality. Stent complications may be associated with the use of drugs such as bevacizumab, an antiangiogenic. Stenting may increase the potential for a successful subsequent laparoscopic tumor resection but may promote tumor dissemination and lymph node invasion and pose an increased risk for perforation, both of which impact disease-free survival. However, many studies comparing stenting to emergency surgery found no difference in recurrence, 3-year, or 5-year mortality.[1]

Etiology-Guided Interventions

For patients with sigmoid volvulus, tube decompression should be attempted with a rigid or flexible sigmoidoscope. A rectal tube is left in place following successful decompression to allow egress of gas and prevent recurrence. Many cases of sigmoid volvulus ultimately require resection or fixation of the sigmoid colon. Patients who cannot be decompressed require more urgent surgery.[1][42][43] A cecal volvulus typically mandates more urgent intervention. In limited cases, the intervention for a cecal volvulus may consist of fixation rather than resection. Creating a cecostomy, while the least invasive, carries the highest mortality and complication risk compared to the relatively low mortality of resection.(A1)

An incarcerated hernia may be successfully reduced, but surgery is required for irreversible ischemia and an irreducible or strangulated hernia.[14] Obstruction from endometriosis can be treated with stenting or resection. Retroperitoneal fibrosis is responsive to steroids and immunomodulation, but a large bowel obstruction from this etiology typically requires surgery. If a colonic stricture is identified during an evaluation for a large bowel obstruction, it is important to rule out malignancy before deciding upon an intervention.[8]

A person diagnosed with pseudo-obstruction may benefit from neostigmine, an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, which can resolve the pseudo-obstruction in up to 94% of cases. A standard dose is 2.0 mg of intravenous neostigmine, with bradycardia being a common side effect that can be treated with atropine.[14] If pharmacologic treatment is not successful, patients require decompression or surgery, which carries additional risks due to bowel distension.[14][19] Patients with impending perforation, cecal ischemia, or fecal peritonitis require an emergency intervention. A cecostomy can be performed on a viable bowel or during right colectomy, as opposed to subtotal colectomy for ischemia and perforation. Tube cecostomy may be a viable option for patients who are stable but have not resolved and can performed through an open, laparoscopic, or percutaneous approach.[14]

Alternative Interventions

Adjuncts and alternative treatments have been used for colonic obstruction. Laser coagulation may facilitate the dilation of benign strictures, but treating the underlying cause is essential. For example, antituberculosis medications are used for an obstruction from tuberculosis. Disimpaction may be attempted, digitally or through an enema, for a nonperforated, obstructing stool impaction. If successful, this is followed by a maintenance bowel regimen. Alternatives to surgery have been described for pathology within the colon, including the use of fibrin glue for fistulae and perforations, but the recurrence rate is high with these modalities. Endoscopic treatments have been applied selectively, including through-the-scope and over-the-scope methods, endoscopic suturing, and tracking systems.[35]

Differential Diagnosis

Colon function may be disrupted by both mechanical and functional processes, including:

- Diverticulitis

- Malignancy

- Small bowel obstruction

- Abdominal hernia

- Appendicitis

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- Systemic or localized inflammatory process

- Carcinomatosis

- Ileus

- Colonic pseudo-obstruction

- Toxic megacolon

- Ischemic colitis

- Mesenteric ischemia

- Volvulus

- Abscess

- Colonic intussusception

- Foreign body

- Infection

- Radiation

- Anatomic variant

Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

In 2022, the Colorectal Endoscopic Stenting Trial (CReST) demonstrated that stenting for left-sided colon malignancy alleviated obstruction in 82% of patients and reduced the rate of emergent stoma formation without a difference in 30-day mortality or 3-year recurrence rates.[44]

In 2022, Kanaka et al. analyzed complications and mortality rates associated with stenting for right-sided colon cancers as a bridge to surgery versus emergency resection. Their findings indicated that stenting led to fewer postoperative complications and lower mortality compared to emergency surgery.[45]

A retrospective study conducted in China examined 1474 individuals who underwent surgery for colonic obstruction and identified factors related to diagnosis and prognosis. The authors found biologic markers, cell populations, and enzymes positively correlated with obstruction, including carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9), carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA-125), neutrophil and lymphocyte counts, and alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase.[46]

A study from the Netherlands in 2021 found a correlation between a longer time to elective surgery following a bridge-to-surgery procedure and overall survival. The authors compared time intervals of greater than and less than 4 weeks to elective surgery for patients who initially underwent temporizing measures for obstructed left-sided colon cancer. In the study, 38 patients underwent intervention before and 56 after 4 weeks, and those with the longer wait time had improved overall survival.[47]

Kwaan et al. studied the effect of time-to-intervention for a large bowel obstruction on morbidity and mortality in a group who were admitted and underwent a procedure consisting of colectomy, stoma, or stenting within 2 days of hospital admission. The authors found that quick intervention resulted in shorter hospital stays but did not impact mortality in their cohort.[18]

Prognosis

In 2023, Eugene et al. created a model for the prediction of 30-day mortality after surgery for acute abdomen, including colon obstruction, based on 13 preoperative characteristics. These factors include age, blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory history, biochemical markers, predicted diagnosis of malignancy, predicted intraoperative contamination, ASA status, and indication for surgery. The model was designed to facilitate treatment discussions and help reduce morbidity and mortality.[48]

Emergency intervention for malignant obstruction reduces long-term survival, and obstructed malignancy is associated with worse overall survival compared to non-obstructed malignancy.[6] Reported mortality for emergency surgery for obstructed colorectal cancer is greater than 11%. Factors associated with a poor outcome include age older than 70, right-sided obstruction, a significant departure from ideal body weight, sepsis, and elevated creatinine. Chronic diseases, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and diabetes, are associated with poor prognoses.[5] In a study involving 30,000 patients admitted with large bowel obstruction, those with a benign process had the highest inpatient mortality.[18]

Complications

Large bowel obstruction can lead to numerous complications, either from the obstruction itself or attempted intervention. Potential issues include perforation, bleeding, fistula formation, and ischemia.[35] Perforation may occur from excessive distension or as the result of instrumentation. According to the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, a perforation caused by stent placement is reported to occur between 2% and 9%. In addition to gross perforations, occult or micro-perforations may occur with the possible dissemination of malignancy.[33] Surgical site infections are common following emergency surgery for colon obstruction, and colostomy reversal is associated with anastomotic leak, with a reported mortality of 8.3%.[5][49]

Consultations

Providing care for a patient with a large bowel obstruction requires collaboration among various specialties, including gastroenterology, interventional radiology, medical and surgical oncology, and colorectal surgery.

Deterrence and Patient Education

An increasing incidence of colorectal cancer in individuals younger than 50 has been observed, and clinicians should be prepared to discuss this trend with their patients and provide education and screening recommendations.[50]

Pearls and Other Issues

In medical centers with interventional radiologists or gastroenterologists, a colonic stent can be inserted using a colonoscope under direct visualization to decompress the bowel and allow for elective surgery when the patient has been clinically optimized. In facilities without advanced technology or expertise, a rectal or nasogastric tube may allow for temporary decompression, but a stoma or resection is often necessary. Patients with a large bowel obstruction from any etiology should be closely monitored. The duration of abdominal distension is more closely associated with the risk for perforation than absolute diameter, and lack of timely intervention can result in significant clinical consequences.[18] Clinicians must maintain a high index of suspicion for any indication of perforation, including the possibility of missing an occult perforation on an x-ray or ultrasound.[1]

The morbidity and mortality of large bowel obstruction depend on the etiology and presence of comorbidities. In most cases, early intervention results in better outcomes. Mortality is significantly higher with bowel perforation or necrosis. Mortality rates of 15% to 30% have been reported in patients with perforation during large bowel obstruction. Recent use of self-expandable metallic stents for malignant bowel obstruction has yielded good short-term results, but long-term survival is not greatly altered.[17][51]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Managing large bowel obstruction requires an interprofessional approach with coordinated communication among healthcare team members. Clinicians, including surgeons, gastroenterologists, oncologists, and radiologists, play a central role in diagnosis, imaging interpretation, and surgical intervention, supported by interventionalists and intensivists when critical. Nurses and advanced practitioners maintain ongoing monitoring and patient education, whereas pharmacists contribute expertise on medications, including antibiotics and pain management.

After surgery, dietitians provide nutritional guidance to patients with ileostomies or colostomies, who also receive specialized care from a stoma nurse. Physical, occupational, and respiratory therapists support rehabilitation, whereas patient navigators ensure continuity of care, especially for oncology follow-up. Effective team communication, particularly in the operating room and intensive care settings, is essential to adjust treatment in response to changing physiological conditions, promoting patient safety, optimizing outcomes, and supporting patient-centered recovery.

Media

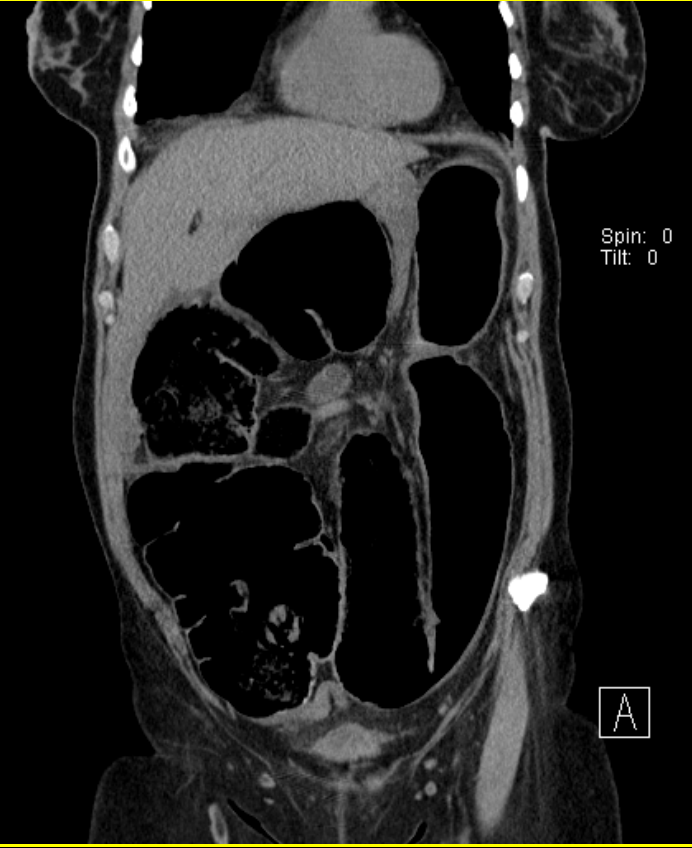

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Cecal Volvulus. Coronal computed tomography of the abdomen reveals a cecal volvulus. Typically, a patient with a cecal volvulus presents with small and large bowel obstructions, characterized by collapse of the distal large bowel and extensive dilation of the proximal small bowel.

Wyckoff Height Medical Center

References

Pisano M, Zorcolo L, Merli C, Cimbanassi S, Poiasina E, Ceresoli M, Agresta F, Allievi N, Bellanova G, Coccolini F, Coy C, Fugazzola P, Martinez CA, Montori G, Paolillo C, Penachim TJ, Pereira B, Reis T, Restivo A, Rezende-Neto J, Sartelli M, Valentino M, Abu-Zidan FM, Ashkenazi I, Bala M, Chiara O, De' Angelis N, Deidda S, De Simone B, Di Saverio S, Finotti E, Kenji I, Moore E, Wexner S, Biffl W, Coimbra R, Guttadauro A, Leppäniemi A, Maier R, Magnone S, Mefire AC, Peitzmann A, Sakakushev B, Sugrue M, Viale P, Weber D, Kashuk J, Fraga GP, Kluger I, Catena F, Ansaloni L. 2017 WSES guidelines on colon and rectal cancer emergencies: obstruction and perforation. World journal of emergency surgery : WJES. 2018:13():36. doi: 10.1186/s13017-018-0192-3. Epub 2018 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 30123315]

Toumi O, Hamida B, Njima M, Bouchrika A, Ammar H, Daldoul A, Zaied S, Ben Jabra S, Gupta R, Noomen F, Zouari K. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the right colon: A case report and review of the literature. International journal of surgery case reports. 2018:50():119-121. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2018.07.001. Epub 2018 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 30103094]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGirão de Caires F, Nunes M, Flores P, Girão de Caires A, Dionísio I. Bowel Obstruction as the Initial Presentation of Urothelial Carcinoma. Cureus. 2024 Jul:16(7):e64056. doi: 10.7759/cureus.64056. Epub 2024 Jul 8 [PubMed PMID: 39114229]

Fardanesh A, George J, Hughes D, Stavropoulou-Tatla S, Mathur P. The use of self-expanding metallic stents in the management of benign colonic obstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Techniques in coloproctology. 2024 Jul 19:28(1):85. doi: 10.1007/s10151-024-02959-7. Epub 2024 Jul 19 [PubMed PMID: 39028327]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePavlidis ET, Galanis IN, Pavlidis TE. Management of obstructed colorectal carcinoma in an emergency setting: An update. World journal of gastrointestinal oncology. 2024 Mar 15:16(3):598-613. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v16.i3.598. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38577464]

Kato H, Kawai K, Nakano D, Dejima A, Ise I, Natsume S, Takao M, Shibata S, Iizuka T, Akimoto T, Tsukada Y, Ito M. Does Colorectal Stenting as a Bridge to Surgery for Obstructive Colorectal Cancer Increase Perineural Invasion? Journal of the anus, rectum and colon. 2024:8(3):195-203. doi: 10.23922/jarc.2023-057. Epub 2024 Jul 30 [PubMed PMID: 39086875]

Flores M, Moughnyeh MM, Lekanides A, Parker L. Acute Constipation and A Stercoral Perforation: A Case Report. SAGE open medical case reports. 2024:12():2050313X241263756. doi: 10.1177/2050313X241263756. Epub 2024 Jul 24 [PubMed PMID: 39055668]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJohnson WR, Hawkins AT. Large Bowel Obstruction. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery. 2021 Jul:34(4):233-241. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1729927. Epub 2021 Jul 20 [PubMed PMID: 34305472]

Quinn K, Davis ME, Carter L, Shortell CK, Sommer C. Emergency General Surgery-A Misnomer? The American surgeon. 2018 Jul 1:84(7):1214-1216 [PubMed PMID: 30064591]

De Monti M, Cestaro G, Alkayyali S, Galafassi J, Fasolini F. Gallstone ileus: A possible cause of bowel obstruction in the elderly population. International journal of surgery case reports. 2018:43():18-20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2018.01.010. Epub 2018 Feb 4 [PubMed PMID: 29414501]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFenaroli P, Maritati F, Vaglio A. Into Clinical Practice: Diagnosis and Therapy of Retroperitoneal Fibrosis. Current rheumatology reports. 2021 Feb 10:23(3):18. doi: 10.1007/s11926-020-00966-9. Epub 2021 Feb 10 [PubMed PMID: 33569638]

Singh A, Paruthy SB, Kuraria V, Aradhya PS. Unusual Triggers of Acute Intestinal Obstruction in Surgical Emergencies: A Series of Five Cases. Cureus. 2024 May:16(5):e60848. doi: 10.7759/cureus.60848. Epub 2024 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 38910718]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBurgos-Torres MDM, Molina-Lopez VH, Perez Cruz NM, Perez Del Valle C, Sorrentino J. Multivitamin-Induced Pharmacobezoar: A Rare Entity of Large Bowel Obstruction. Cureus. 2023 Jul:15(7):e41688. doi: 10.7759/cureus.41688. Epub 2023 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 37441102]

Underhill J, Munding E, Hayden D. Acute Colonic Pseudo-obstruction and Volvulus: Pathophysiology, Evaluation, and Treatment. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery. 2021 Jul:34(4):242-250. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1727195. Epub 2021 Jul 20 [PubMed PMID: 34305473]

Drożdż W, Budzyński P. Change in mechanical bowel obstruction demographic and etiological patterns during the past century: observations from one health care institution. Archives of surgery (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2012 Feb:147(2):175-80. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.970. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22351915]

Shah D, Makharia GK, Ghoshal UC, Varma S, Ahuja V, Hutfless S. Burden of gastrointestinal and liver diseases in India, 1990-2016. Indian journal of gastroenterology : official journal of the Indian Society of Gastroenterology. 2018 Sep:37(5):439-445. doi: 10.1007/s12664-018-0892-3. Epub 2018 Oct 10 [PubMed PMID: 30306342]

Doshi R, Desai J, Shah Y, Decter D, Doshi S. Incidence, features, in-hospital outcomes and predictors of in-hospital mortality associated with toxic megacolon hospitalizations in the United States. Internal and emergency medicine. 2018 Sep:13(6):881-887. doi: 10.1007/s11739-018-1889-8. Epub 2018 Jun 12 [PubMed PMID: 29948833]

Kwaan MR, Wu Y, Ren Y, Xirasagar S. Prompt intervention in large bowel obstruction management: A Nationwide Inpatient Sample analysis. American journal of surgery. 2022 Nov:224(5):1262-1266. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2022.07.002. Epub 2022 Jul 19 [PubMed PMID: 35922257]

Jaffe T, Thompson WM. Large-Bowel Obstruction in the Adult: Classic Radiographic and CT Findings, Etiology, and Mimics. Radiology. 2015 Jun:275(3):651-63. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015140916. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25997131]

Naiem MEA, Suliman SH. Cecal perforations due to descending colon obstruction (closed loop): a case report and review of the literature. Journal of medical case reports. 2022 Dec 5:16(1):450. doi: 10.1186/s13256-022-03674-3. Epub 2022 Dec 5 [PubMed PMID: 36471445]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCatena F, De Simone B, Coccolini F, Di Saverio S, Sartelli M, Ansaloni L. Bowel obstruction: a narrative review for all physicians. World journal of emergency surgery : WJES. 2019:14():20. doi: 10.1186/s13017-019-0240-7. Epub 2019 Apr 29 [PubMed PMID: 31168315]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVeld JV, Beek KJ, Consten ECJ, Ter Borg F, van Westreenen HL, Bemelman WA, van Hooft JE, Tanis PJ. Definition of large bowel obstruction by primary colorectal cancer: A systematic review. Colorectal disease : the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. 2021 Apr:23(4):787-804. doi: 10.1111/codi.15479. Epub 2021 Jan 15 [PubMed PMID: 33305454]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDolejs SC, Guzman MJ, Fajardo AD, Holcomb BK, Robb BW, Waters JA. Contemporary Management of Sigmoid Volvulus. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery : official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 2018 Aug:22(8):1404-1411. doi: 10.1007/s11605-018-3747-4. Epub 2018 Mar 22 [PubMed PMID: 29569006]

Wasanwala H, Neychev V. Perforated Colon Cancer Associated With Post-operative Recurrent Bowel Perforations. Cureus. 2021 Sep:13(9):e17655. doi: 10.7759/cureus.17655. Epub 2021 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 34646700]

Cinar H, Berkesoglu M, Derebey M, Karadeniz E, Yildirim C, Karabulut K, Kesicioglu T, Erzurumlu K. Surgical management of anorectal foreign bodies. Nigerian journal of clinical practice. 2018 Jun:21(6):721-725. doi: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_172_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29888718]

Orgul G, Soyer T, Yurdakok M, Beksac MS. Evaluation of pre- and postnatally diagnosed gastrointestinal tract obstructions. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstetricians. 2019 Oct:32(19):3215-3220. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1460350. Epub 2018 Apr 12 [PubMed PMID: 29606013]

Syrmis W, Richard R, Jenkins-Marsh S, Chia SC, Good P. Oral water soluble contrast for malignant bowel obstruction. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2018 Mar 7:3(3):CD012014. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012014.pub2. Epub 2018 Mar 7 [PubMed PMID: 29513393]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHokama A, Iraha A. Coffee bean sign, steel pan sign and whirl sign in sigmoid volvulus. Revista espanola de enfermedades digestivas. 2024 Feb:116(2):114-115. doi: 10.17235/reed.2022.9262/2022. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36263824]

Stavride E, Plakias C. Coffee bean sign: Its meaning and importance. Clinical case reports. 2020 Oct:8(10):2086-2087. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.3064. Epub 2020 Jun 26 [PubMed PMID: 33088563]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSpada C, Hassan C, Bellini D, Burling D, Cappello G, Carretero C, Dekker E, Eliakim R, de Haan M, Kaminski MF, Koulaouzidis A, Laghi A, Lefere P, Mang T, Milluzzo SM, Morrin M, McNamara D, Neri E, Pecere S, Pioche M, Plumb A, Rondonotti E, Spaander MC, Taylor S, Fernandez-Urien I, van Hooft JE, Stoker J, Regge D. Imaging alternatives to colonoscopy: CT colonography and colon capsule. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) and European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR) Guideline - Update 2020. European radiology. 2021 May:31(5):2967-2982. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-07413-4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33104846]

Kwaan MR, Ren Y, Wu Y, Xirasagar S. Colonic Stent Use by Indication and Patient Outcomes: A Nationwide Inpatient Sample Study. The Journal of surgical research. 2021 Sep:265():168-179. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2021.03.048. Epub 2021 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 33940240]

van Hooft JE, Veld JV, Arnold D, Beets-Tan RGH, Everett S, Götz M, van Halsema EE, Hill J, Manes G, Meisner S, Rodrigues-Pinto E, Sabbagh C, Vandervoort J, Tanis PJ, Vanbiervliet G, Arezzo A. Self-expandable metal stents for obstructing colonic and extracolonic cancer: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - Update 2020. Endoscopy. 2020 May:52(5):389-407. doi: 10.1055/a-1140-3017. Epub 2020 Apr 7 [PubMed PMID: 32259849]

Vogel JD, Felder SI, Bhama AR, Hawkins AT, Langenfeld SJ, Shaffer VO, Thorsen AJ, Weiser MR, Chang GJ, Lightner AL, Feingold DL, Paquette IM. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Colon Cancer. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2022 Feb 1:65(2):148-177. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000002323. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34775402]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMashar M, Mashar R, Hajibandeh S. Uncovered versus covered stent in management of large bowel obstruction due to colorectal malignancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of colorectal disease. 2019 May:34(5):773-785. doi: 10.1007/s00384-019-03277-3. Epub 2019 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 30903271]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGordon SR, Eichenwald LS, Systrom HK. Endoscopic techniques for management of large colorectal polyps, strictures and leaks. Surgery open science. 2024 Aug:20():156-168. doi: 10.1016/j.sopen.2024.06.012. Epub 2024 Jul 4 [PubMed PMID: 39100384]

Sasaki T, Yoshida S, Isayama H, Narita A, Yamada T, Enomoto T, Sumida Y, Kyo R, Kuwai T, Tomita M, Moroi R, Shimada M, Hirata N, Saida Y. Short-Term Outcomes of Colorectal Stenting Using a Low Axial Force Self-Expandable Metal Stent for Malignant Colorectal Obstruction: A Japanese Multicenter Prospective Study. Journal of clinical medicine. 2021 Oct 26:10(21):. doi: 10.3390/jcm10214936. Epub 2021 Oct 26 [PubMed PMID: 34768456]

Balciscueta I, Balciscueta Z, Uribe N, García-Granero E. Perineural invasion is increased in patients receiving colonic stenting as a bridge to surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Techniques in coloproctology. 2021 Feb:25(2):167-176. doi: 10.1007/s10151-020-02350-2. Epub 2020 Nov 17 [PubMed PMID: 33200308]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGavriilidis P, de'Angelis N, Wheeler J, Askari A, Di Saverio S, Davies JR. Diversion, resection, or stenting as a bridge to surgery for acute neoplastic left-sided colonic obstruction: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of studies with curative intent. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2021 Apr:103(4):235-244. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2020.7137. Epub 2021 Mar 8 [PubMed PMID: 33682486]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceZwanenburg ES, Veld JV, Amelung FJ, Borstlap WAA, Dekker JWT, Hompes R, Tuynman JB, Westerterp M, van Westreenen HL, Bemelman WA, Consten ECJ, Tanis PJ, On behalf of the Dutch Snapshot Research Group. Short- and Long-term Outcomes After Laparoscopic Emergency Resection of Left-Sided Obstructive Colon Cancer: A Nationwide Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2023 Jun 1:66(6):774-784. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000002364. Epub 2023 May 4 [PubMed PMID: 35522731]

Boeding JRE, Ramphal W, Rijken AM, Crolla RMPH, Verhoef C, Gobardhan PD, Schreinemakers JMJ. A Systematic Review Comparing Emergency Resection and Staged Treatment for Curable Obstructing Right-Sided Colon Cancer. Annals of surgical oncology. 2021 Jul:28(7):3545-3555. doi: 10.1245/s10434-020-09124-y. Epub 2020 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 33067743]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKondo A, Okano K, Kumamoto K, Kobara H, Nagahara T, Wato M, Shibatoge M, Minato T, Masaki T, Suzuki Y, Kagawa Gastroenterology Forum. Surgical management and outcomes of obstructive colorectal cancer in elderly patients: A multi-institutional retrospective study. Surgery. 2022 Jul:172(1):60-68. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2021.12.007. Epub 2022 Jan 5 [PubMed PMID: 34998620]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFarkas N, Kaur V, Shanmuganandan A, Black J, Redon C, Frampton AE, West N. A systematic review of gallstone sigmoid ileus management. Annals of medicine and surgery (2012). 2018 Mar:27():32-39. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2018.01.004. Epub 2018 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 29511540]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDi Saverio S, Birindelli A, Segalini E, Novello M, Larocca A, Ferrara F, Binda GA, Bassi M. "To stent or not to stent?": immediate emergency surgery with laparoscopic radical colectomy with CME and primary anastomosis is feasible for obstructing left colon carcinoma. Surgical endoscopy. 2018 Apr:32(4):2151-2155. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5763-y. Epub 2017 Aug 8 [PubMed PMID: 28791424]

CReST Collaborative Group. Colorectal Endoscopic Stenting Trial (CReST) for obstructing left-sided colorectal cancer: randomized clinical trial. The British journal of surgery. 2022 Oct 14:109(11):1073-1080. doi: 10.1093/bjs/znac141. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35986684]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKanaka S, Matsuda A, Yamada T, Ohta R, Sonoda H, Shinji S, Takahashi G, Iwai T, Takeda K, Ueda K, Kuriyama S, Miyasaka T, Yoshida H. Colonic stent as a bridge to surgery versus emergency resection for right-sided malignant large bowel obstruction: a meta-analysis. Surgical endoscopy. 2022 May:36(5):2760-2770. doi: 10.1007/s00464-022-09071-7. Epub 2022 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 35113211]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCao Y, Ke S, Gu J, Mao F, Yao S, Deng S, Yan L, Wu K, Liu L, Cai K. The Value of Haematological Parameters and Tumour Markers in the Prediction of Intestinal Obstruction in 1474 Chinese Colorectal Cancer Patients. Disease markers. 2020:2020():8860328. doi: 10.1155/2020/8860328. Epub 2020 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 32855747]

de Roos MAJ, Hugen N, Hazebroek EJ, Spillenaar Bilgen EJ. Delayed surgical resection of primary left-sided obstructing colon cancer is associated with improved short- and long-term outcomes. Journal of surgical oncology. 2021 Dec:124(7):1146-1153. doi: 10.1002/jso.26632. Epub 2021 Aug 4 [PubMed PMID: 34346510]

Eugene N, Kuryba A, Martin P, Oliver CM, Berry M, Moppett IK, Johnston C, Hare S, Lockwood S, Murray D, Walker K, Cromwell DA, NELA Project Team. Development and validation of a prognostic model for death 30 days after adult emergency laparotomy. Anaesthesia. 2023 Oct:78(10):1262-1271. doi: 10.1111/anae.16096. Epub 2023 Jul 14 [PubMed PMID: 37450350]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceManceau G, Voron T, Mege D, Bridoux V, Lakkis Z, Venara A, Beyer-Berjot L, Abdalla S, Sielezneff I, Lefèvre JH, Karoui M, AFC (French Surgical Association) Working Group. Prognostic factors and patterns of recurrence after emergency management for obstructing colon cancer: multivariate analysis from a series of 2120 patients. Langenbeck's archives of surgery. 2019 Sep:404(6):717-729. doi: 10.1007/s00423-019-01819-5. Epub 2019 Oct 10 [PubMed PMID: 31602503]

Dharwadkar P, Zaki TA, Murphy CC. Colorectal Cancer in Younger Adults. Hematology/oncology clinics of North America. 2022 Jun:36(3):449-470. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2022.02.005. Epub 2022 May 13 [PubMed PMID: 35577711]

Matsuda A, Miyashita M, Matsumoto S, Sakurazawa N, Kawano Y, Yamahatsu K, Sekiguchi K, Yamada M, Hatori T, Yoshida H. Colonic stent-induced mechanical compression may suppress cancer cell proliferation in malignant large bowel obstruction. Surgical endoscopy. 2019 Apr:33(4):1290-1297. doi: 10.1007/s00464-018-6411-x. Epub 2018 Aug 31 [PubMed PMID: 30171397]