Introduction

Tricuspid valve infective endocarditis (TVIE) is uncommon compared to left-sided infective endocarditis. Right-sided infective endocarditis (RSIE) accounts for approximately 5% to 10% of all cases of infective endocarditis (IE).[1] The overwhelming number of cases of RSIE involve the tricuspid valve, with some estimates as high as 90%. The majority of isolated TVIE are associated with intravenous drug use (IVDU). Given the rise of IVDU in the United States (US), rates of TVIE have also increased significantly since 2006.[2] Along with IVDU, hemodialysis catheters, pacemakers, and defibrillator leads are also risk factors. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common organism that causes TVIE.

However, various skin flora, as well as various Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species, can infect the tricuspid valve. The modified Duke Criteria are used to establish the diagnosis of TVIE. However, certain aspects of TVIE can make detection difficult. Such features include absent murmur, concurrent pneumonia, and less peripheral phenomena such as splinter hemorrhages.[3] Regardless, TVIE is treatable and has favorable outcomes if detected and treated early in its course. Although RSIE and TVIE are increasing in prevalence, antibiotics and surgical options remain a mainstay of successful treatment.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

TVIE is a serious condition predominantly affecting individuals with specific risk factors such as IVDU, cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs), and indwelling catheters. IVDU is the leading cause of TVIE, accounting for 30% to 40% of cases due to repeated introduction of pathogens into the bloodstream through nonsterile injections. CIED-related TVIE occurs when valvular vegetations and tricuspid regurgitation are evident in positive blood cultures. Similarly, patients requiring long-term central venous access for hemodialysis, parenteral nutrition, or chemotherapy are predisposed due to potential bloodstream infections. These factors create conditions conducive to microbial adherence and infection of the tricuspid valve.

Bacterial Etiology

The microbial profile of TVIE largely aligns with that of IE in general. Diagnostic protocols emphasize obtaining 3 aerobic blood cultures from separate venipuncture sites, spaced at least 1 hour apart, using strict aseptic techniques and ideally before initiating antibiotic therapy. Although anaerobic cultures may be considered, true anaerobic pathogens are rare in TVIE. If the patient has already received antibiotics or initial cultures yield no growth, additional blood cultures may improve diagnostic yield. These protocols are critical to identifying causative organisms and guiding targeted therapy.

Role of Specific Pathogens

- Staphylococcus aureus

- Staphylococcus aureus is the most frequently isolated bacterium in TVIE and is the second leading cause of hospital-acquired bacteremia in the US. The annual incidence of S aureus bacteremia (SAB) varies between 4.3 and 38.2 cases per 100,000 person-years, depending on population demographics. IE occurs in approximately 5% to 30% of these cases, depending on region, patient demographics, and diagnostic methods. For example, Rasmussen et al reported only a 5% prevalence of IE in low-risk patients with S aureus infection compared to 38% in those with high-risk factors.[4] S aureus-endocarditis now constitutes 25% to 30% of all endocarditis cases globally, with methicillin-resistant S aureus (eg, MRSA) comprising approximately 37% of all cases in the US and Brazil. The rise in S aureus endocarditis is primarily attributed to IVDU in urban areas, increased cardiac surgeries and invasive procedures, and the widespread use of intravenous catheters in hospitalized patients.

- Identifying the entry point for SAB can be challenging, with no apparent source identified in 22% to 48% of cases. This uncertainty is more common in community-acquired than hospital-acquired SAB. Community-acquired SAB is considered an independent risk factor for IE, particularly without other apparent infection sources. Research results have shown variability in the risk of IE in catheter-associated SAB. Joseph et al reported a low likelihood of IE in SAB cases associated with intravenous catheters without other infection sources or intracardiac devices. Conversely, Fernandez Guerrero et al suggested catheter-related SAB may represent an underdiagnosed cause of IE, especially with right-sided valve involvement. In these cases, clinical signs may be subtle, necessitating a high index of suspicion to avoid missed diagnoses.[5][6]

- Streptococcus bovis complex

- The Streptococcus bovis complex, comprising S bovis, S equinus, S gallolyticus, S infantarius, S pasteurianus, and S lutetiensis, is part of the group D nonenterococcal streptococci found in the human intestinal flora. This evolving taxonomy highlights the need for clinician awareness, as misclassification can lead to underdiagnosing serious conditions. Epidemiologic data from the International Collaboration on Endocarditis show a significant rise in S bovis complex-related IE cases, from 10.9% pre-1989 to 23.3% post-1989, emphasizing its growing clinical relevance.

- The S bovis complex shares virulence and antimicrobial susceptibility profiles with viridans group streptococci. However, despite its infrequent use in IE treatment, clindamycin resistance has been noted. Consequently, therapeutic guidelines for these pathogens are largely aligned. However, there are distinct features associated with S bovis complex IE, which fall into 2 categories: characteristics of IE and associated comorbidities.

- Characteristics of IE

- Patients with S bovis complex IE are typically older men with significant comorbidities, often without preexisting valve disease. This IE predominantly affects the mitral valve but may involve the tricuspid valve, especially in prosthetic valve cases. Evidence regarding embolic or neurologic complications in S bovis complex IE compared to viridans IE is inconsistent, but surgical and mortality rates are similar.

- Comorbidities

- The most significant association of S bovis complex bacteremia, particularly with S gallolyticus (formerly S bovis biotype I), is with colonic neoplasms. Studies suggest that 25% to 80% of patients with S bovis bacteremia have colorectal tumors. The hypothesized mechanism involves bacterial proteins triggering chronic inflammation linked to neoplasia. Consequently, patients with S bovis bacteremia or IE should undergo thorough gastrointestinal evaluation, especially colonoscopy. Additional associations include chronic liver disease and certain extraintestinal neoplasms.

- Characteristics of IE

Culture-Negative IE

A small subset of patients with high clinical suspicion for IE may present with negative blood cultures. The most common cause is partial sterilization from prior antibiotic therapy. Other cases involve atypical organisms that are difficult to isolate, such as Coxiella burnetii (Q fever), Tropheryma whipplei, Brucella, Mycoplasma, Chlamydia, Histoplasma, Legionella, Bartonella, and the HACEK group (Haemophilus aphrophilus, Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella corrodens, and Kingella kingae). Extended incubation times may be required for slow-growing organisms like the HACEK group. At the same time, additional diagnostic modalities such as polymerase chain reaction on valve tissue are critical for detecting organisms like C burnetii and Bartonella. In some cases, specialized culture media or serological tests, such as antibody titers for C burnetii, provide diagnostic clarity. A single positive culture for C burnetii can confirm the diagnosis of IE.[7]

Bacteremias Without IE

Certain bacterial species are strongly associated with IE, while others are not. For example, group G streptococci and Enterococcus faecalis have a notable link to IE. In contrast, group A or C streptococci and most gram-negative rods, such as Escherichia coli and Proteus, rarely cause the condition. Organisms like Propionibacterium, Corynebacterium, Bacillus, and coagulase-negative staphylococci found in blood cultures are often skin contaminants rather than true pathogens. Repeating blood cultures under sterile conditions is essential to differentiate contamination from actual bacteremia.[8][9]

Device-Related and Hospital-Acquired Risk Factors

Patients with prosthetic valves or intracardiac devices are particularly susceptible to TVIE, with device-associated cases demonstrating a high mortality rate of approximately 26% despite optimal treatment. Hemodialysis patients also face elevated risks, potentially due to frequent venous catheter use and novel graft materials. These hospital-acquired risk factors underscore the need for stringent infection control practices and careful monitoring of at-risk populations.

Epidemiology

TVIE constitutes a distinct subset of IE, predominantly affecting populations with unique risk factors. Over time, the incidence of TVIE has increased, especially among individuals with IVDU and those requiring indwelling devices. Notably, cases of RSIE, including TVIE, are rising due to the growing prevalence of IVDU and invasive medical interventions.

Changing Demographics

IVDU accounts for approximately 86% of TVIE cases and is a significant driver of its increasing incidence. Results from one study reported a 12% rise in hospitalizations for IVDU-related IE, reflecting the expanding burden of this condition.[10] Traditionally more common in men, TVIE has shown a trend toward normalization of gender ratios over time. The affected population has also become younger and predominantly white, further highlighting the shifting epidemiological patterns.[10]

Risk Factors and Predisposing Conditions

- IVDU

- Repeated exposure to nonsterile injections leads to bacteremia, primarily caused by Staphylococcus aureus, the dominant pathogen in this population.

- Indwelling catheters and cardiac devices

- The increasing use of central venous access for hemodialysis, chemotherapy, and parenteral nutrition, along with the implantation of cardiac devices, has expanded the population at risk for TVIE.

- Healthcare interventions

- The rise in invasive procedures has further contributed to increased healthcare-associated cases.

History and Physical

History

Patients with TVIE and isolated right-sided native valve endocarditis often present with a complex array of nonspecific symptoms influenced by underlying risk factors, the causative organism, and the disease’s severity. These nonspecific constitutional symptoms, including fever, chills, night sweats, and malaise, often delay diagnosis and treatment. Respiratory symptoms such as dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, productive cough, and hemoptysis, typically caused by septic pulmonary emboli, are often the primary reason patients seek medical attention. Unfortunately, these symptoms usually appear only when the disease is already advanced. One study highlights a clinical triad—recurrent pulmonary infections, anemia, and microscopic hematuria, referred to as "the tricuspid syndrome"—as a key indicator of isolated tricuspid valve endocarditis.

A comprehensive history is essential to identify high-risk behaviors, predisposing medical conditions, and clinical clues. IVDU is the most significant risk factor, as recurrent injection drug use with inadequate aseptic techniques leads to recurrent bacteremia. Other risk factors include long-term use of central venous catheters for hemodialysis, chemotherapy, parenteral nutrition, and cardiac implantable electronic devices that predispose patients to device-related endocarditis. Recent hospitalizations, invasive procedures, or surgeries should raise suspicion for healthcare-associated TVIE.

Constitutional symptoms such as anorexia, fatigue, malaise, weight loss, and arthralgia are frequently reported. Respiratory symptoms, including cough, pleuritic chest pain, and dyspnea on exertion, often result from septic pulmonary emboli causing pulmonary infarctions or infections. Abdominal pain may occasionally occur due to embolic phenomena. Cardiovascular findings are often subtle, as cardiac-specific symptoms are typically minimal. However, signs of right-sided heart failure—such as peripheral edema, ascites, and jugular venous distension—may appear in advanced disease. Peripheral phenomena like splinter hemorrhages and cardiac murmurs are uncommon, contributing to the difficulty of diagnosis.

Despite the nonspecific presentation, clinicians must remain vigilant for complications such as recurrent infections, anemia, and embolic phenomena, which may guide the diagnosis of TVIE. Establishing a diagnosis is particularly challenging in subacute presentations or when typical IE features are absent. A thorough review of risk factors and symptoms and awareness of patterns like "the tricuspid syndrome" can help clinicians identify TVIE early and initiate appropriate treatment.

Physical Exam

Physical examination findings in TVIE can be subtle and nonspecific, as the condition primarily involves the right side of the heart. The clinical presentation often reflects systemic manifestations of infection and complications from septic emboli rather than direct cardiac involvement. The following outlines the key physical exam findings associated with TVIE:

- Constitutional Signs

- Fever

- Tachycardia

- Weight loss

- Cardiac Findings

- Murmur

- A systolic murmur, best heard along the lower left sternal border, may be present if there is significant tricuspid regurgitation. However, the murmur may be absent in up to half of patients, especially in early or uncomplicated cases.

- Signs of right-sided heart failure (if advanced)

- Jugular venous distension

- Peripheral edema

- Hepatomegaly and ascites

- Murmur

- Pulmonary Findings

- Rales or crackles

- Pleuritic chest pain with reduced breath sounds

- Hemoptysis

- Peripheral Signs of Endocarditis

- Peripheral manifestations are less common in TVIE than in left-sided IE but may still occur, particularly in cases with systemic spread or embolization:

- Clubbing of fingers

- Painless cutaneous lesions (Janeway lesions)

- Splinter hemorrhages

- Peripheral manifestations are less common in TVIE than in left-sided IE but may still occur, particularly in cases with systemic spread or embolization:

- Skin Findings

- These are mostly found in IVDU patients:

- Injection sites or track marks

- Localized abscesses or cellulitis

- These are mostly found in IVDU patients:

- Abdominal Findings

- Hepatomegaly

- Abdominal tenderness

- General Observations

- Sepsis or septic shock

- Findings of hypotension, altered mental status, or poor perfusion may be seen in severe cases with systemic infection.

- Anemia and pallor

- Sepsis or septic shock

Clinical Implications

The physical exam in TVIE can be unremarkable or reveal only mild abnormalities in the early stages, making diagnosis challenging. However, findings of septic pulmonary emboli, signs of right-sided heart failure, and stigmata of endocarditis in high-risk patients (eg, those with IVDU or central venous catheters) should prompt further diagnostic workup, including blood cultures and echocardiography. Recognizing the subtle and often nonspecific nature of TVIE physical exam findings is critical for early diagnosis and management.

Evaluation

Modified Duke Criteria

The diagnosis of TVIE is based on the modified Duke Criteria. This criterion is widely used to diagnose TVIE, like all other forms of IE. This criterion allows the stratification of IE into a definite, possible, or rejected category. Based on clinical criteria, definite endocarditis is defined as 2 primary criteria, 1 major with 3 minor criteria, or 5 minor. Possible endocarditis is measured by the presence of 1 major with 2 minor criteria or with 3 minor criteria alone.[11] The criteria classes are as follows:

- Major criteria

- Positive blood culture (any of the following):

- Two separate blood cultures yielded positive results for organisms known to cause IE

- Organisms consistent with endocarditis from blood cultures obtained 12 hours apart

- A positive culture for organisms that are common skin contaminants in 3 or the majority of ≥4 separate blood cultures (first and last sample drawn at least 1 hour apart)

- Single positive blood culture of Coxiella burnetti

- Evidence of endocardial involvement (vegetation, abscess, new valvular regurgitation, dehiscence of a prosthetic valve)

- Positive blood culture (any of the following):

- Minor criteria

- Fever >38 °C (100.4 °F)

- Immunologic occurrence: Roth spots, Osler nodes, glomerulonephritis

- Predisposing heart defect or IVDU

- Vascular phenomena: septic emboli, arterial emboli, conjunctival hemorrhages, splinter hemorrhages, Janeway lesions, mycotic aneurysm

- A positive blood culture that does not meet essential criteria

Laboratory Workup

Routine laboratory values in IE are generally nonspecific. A basic workup should be completed. Some abnormalities include leukocytosis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, elevated c-reactive protein, normocytic anemia, or urinalysis revealing hematuria, proteinuria, or pyuria.

Blood cultures are essential in the diagnosis of TVIE. A minimum of 3 sets of blood cultures should be drawn from different venipuncture sites, ensuring they are spaced at least 1 hour apart. This approach maximizes the diagnostic yield by increasing the chances of identifying the causative organism, particularly when the patient has not been pretreated with antibiotics. If initial cultures are negative and there is a high clinical suspicion, further cultures or additional blood samples should be obtained.

Diagnostic Workup

- Electrocardiogram

- Electrocardiograms may reveal conduction disturbances such as heart block.[12] These abnormalities occur due to IE, potentially due to direct invasion of the myocardium or associated septic emboli affecting the conduction system.

- Chest radiograph

- A chest radiograph should be obtained to assess potential pulmonary complications, such as septic emboli or lung infiltrates. Septic emboli are often the result of right-sided endocarditis affecting the tricuspid valve and can manifest as peripheral lung nodules or areas of consolidation. This is critical in patients presenting with respiratory symptoms like cough or dyspnea.

- Computed tomography scan

- A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen can help identify metastatic embolic foci such as splenic or renal infarcts. Embolic phenomena can affect various organs, and identifying these foci is important for understanding the extent of the disease. A low threshold for abdominal CT is advised in patients with suspected TVIE, especially those with unexplained systemic symptoms or signs of organ dysfunction.

- Echocardiography

- Transthoracic echocardiogram

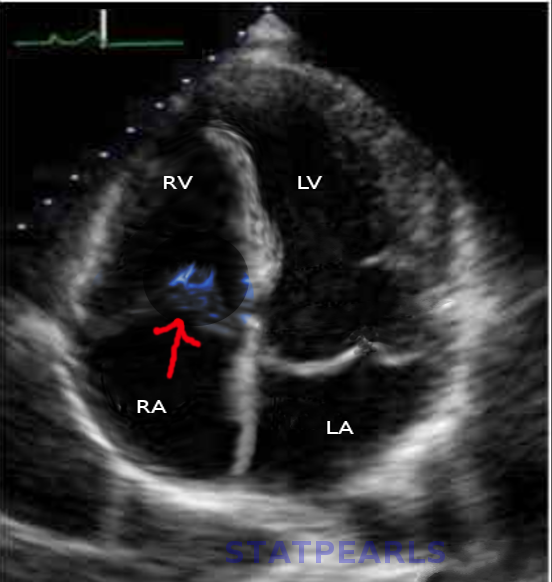

- A transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) is the initial imaging test used to assess the heart valves in suspected cases of TVIE. This modality is highly specific for detecting vegetation on the tricuspid valve, which is characteristic of IE (see Image. Tricuspid Valve Endocarditis on Cardiac Ultrasound). The presence of vegetation or valve regurgitation is highly suggestive of infection.

- Transesophageal echocardiogram

- A transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) should be pursued if TTE results are negative but clinical suspicion remains high. TEE provides better sensitivity, particularly for detecting small vegetations or assessing valve function and anatomy in more complex cases. This modality is especially useful if there is significant valve regurgitation, as it can help determine the extent of the damage and guide decisions regarding surgical intervention.[13]

- Transthoracic echocardiogram

Treatment / Management

The treatment of TVIE involves tailored antibiotic therapy, consideration for surgical intervention in select cases, and management of underlying risk factors. While the standard of care includes prolonged antimicrobial regimens, certain patients with uncomplicated TVIE may be candidates for shorter antibiotic courses, emphasizing the need for individualized treatment plans.

Medical Management Antibiotic Therapy

- Empiric therapy

- Empiric antibiotics should be initiated once TVIE is suspected, ideally after obtaining at least 3 sets of blood cultures.

- Empiric regimens typically include vancomycin, covering Staphylococcus aureus (including methicillin-resistant strains) and streptococci, the most common pathogens associated with TVIE.

- Pathogen-specific therapy

- Adjustments are made based on blood culture results:

- Methicillin-sensitive S aureus

- Switch from vancomycin to nafcillin, oxacillin, or cefazolin for 4 to 6 weeks.

- MRSA

- Continue vancomycin or daptomycin for 6 weeks.

- HACEK organisms

- Ceftriaxone or another beta-lactam for 4 weeks is typically effective.

- Polymicrobial or fungal infections

- These often require combined medical and surgical treatment, with antifungal agents such as amphotericin B for fungal cases.

- Methicillin-sensitive S aureus

- Adjustments are made based on blood culture results:

- Short-course therapy

- Select patients with uncomplicated TVIE (eg, no renal failure, left-sided infection, or extrapulmonary complications) may be considered for a 2-week antibiotic course. Candidates include those with isolated TVIE caused by susceptible organisms, such as HACEK organisms or methicillin-susceptible S aureus, without evidence of metastatic infection.[14]

- This approach is inappropriate for cases involving prosthetic valves, MRSA, or complicated infections.[15]

- Duration of therapy

- For most cases, antibiotics should be continued for 6 weeks from the date of the first negative blood culture, ensuring complete eradication of the infection.

- Supportive care

- Manage complications, such as septic shock or pulmonary embolism.

- Monitor renal function during prolonged antibiotic therapy, particularly with agents like vancomycin or aminoglycosides.

(B3)

Surgical Management

Surgical treatment is considered for patients with severe or refractory disease.

- Indications

- Large vegetations

- Tricuspid vegetations >2 cm, especially with recurrent septic pulmonary emboli

- Persistent bacteremia

- Ongoing bacteremia for more than 7 days despite adequate antimicrobial therapy

- Severe tricuspid regurgitation

- Causing symptomatic right-sided heart failure unresponsive to medical treatment [16]

- Large vegetations

- Surgical procedures

- Vegetation removal or valve repair

- Preferred when technically feasible to preserve native valve function.

- Valve replacement

- Bioprosthetic valves are often favored to avoid long-term anticoagulation, though reinfection risk remains high, particularly in patients with ongoing IVDU.

(A1) - Vegetation removal or valve repair

Management of Underlying Risk Factors

- IVDU

- Counseling and referral to substance use treatment programs are critical.

- Medication-assisted therapy (eg, buprenorphine or methadone) and harm reduction strategies (eg, needle exchange programs) reduce reinfection risk.

- Removal of infectious sources

- Central venous catheters or infected devices (eg, pacemakers) must be removed to eliminate sources of bacteremia.

Monitoring and Follow-Up

- Blood cultures

- Regular monitoring ensures clearance of bacteremia and guides therapy duration.

- Echocardiography

- Follow-up imaging monitors vegetation size, valve function, and resolution of infection.

- Outpatient follow-up

- Continued care is essential to monitor for recurrence, address comorbidities, and ensure adherence to therapy and risk factor management.

Clinical Considerations

Symptoms in TVIE, including fever, chills, dyspnea, and hemoptysis, often stem from septic pulmonary emboli. However, these symptoms typically appear in advanced disease stages, which can delay diagnosis. Patients presenting with complications, such as recurrent pulmonary infections, should prompt suspicion of TVIE.

Differential Diagnosis

In any form, IE can be challenging to identify due to its nonspecific presentation and overlap with various autoimmune, infectious, and neoplastic conditions. IE should be approached as a syndrome, recognizing its broad clinical manifestations and employing comprehensive diagnostic tools such as the modified Duke Criteria, which integrates clinical, microbiological, and echocardiographic findings. The differential diagnosis for IE includes:

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Polymyalgia rheumatic

- Lyme disease

- Antiphospholipid syndrome

- Libman-Sacks endocarditis

- Atrial myxoma

- Rheumatic fever

- Marantic endocarditis

Prognosis

The overall in-hospital mortality rate for TVIE ranges from 10% to 15%, notably lower than that observed in left-side IE. Patients with TVIE related to IVDU who adhere to treatment and avoid severe complications typically achieve favorable recovery rates. However, relapse is common among those with continued exposure to risk factors, such as ongoing IVDU or persistent bacteremia due to retained hardware.

Patients successfully treated for TVIE often have good long-term survival if modifiable risk factors are addressed and recurrence is prevented. Compared to other forms of IE, TVIE is associated with a better overall prognosis.[17] The fatality rate is lower, with a study reporting an overall mortality rate of 6% in cases of native valve endocarditis.[18] Prognosis is influenced by vegetation size; vegetation larger than 1 cm significantly increases mortality risk.

Concurrent involvement of the left-sided valves worsens outcomes due to the higher likelihood of complications such as abscess formation.[1] For patients with structural damage to the tricuspid valve, long-term monitoring is critical to detect and manage complications such as heart failure or the need for surgical intervention. Preventing recurrence through comprehensive addiction treatment programs, minimizing invasive procedures, and implementing prophylactic measures are essential strategies for improving long-term outcomes.

Complications

TVIE can lead to a range of complications that stem from the infection itself, the presence of vegetations, and the systemic effects of embolic phenomena. These complications can significantly impact prognosis and require prompt recognition and management.[19] These include:

- Cardiac Complications

- Severe tricuspid regurgitation

- Right-sided heart failure

- Valve perforation or rupture

- Abscess formation or involvement of the annulus or myocardium

- Conduction abnormalities

- Embolic Complications

- Septic pulmonary emboli

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Infectious Complications

- Persistent bacteremia

- Sepsis and septic shock

- Abscesses in distant organs (eg, liver, spleen, kidneys) or osteomyelitis

- Mycotic aneurysm

- Systemic and other organ complications

- Acute kidney injury

- Liver dysfunction

Consultations

IE requires management by an interdisciplinary team of clinicians, including:

- Internal medicine

- Infectious disease

- Cardiology

- Cardiothoracic surgery

- Nursing staff

Deterrence and Patient Education

Effective deterrence and patient education are critical in preventing the recurrence of TVIE, particularly in high-risk populations such as individuals with IVDU or those with indwelling medical devices. For patients with a history of IVDU, enrolling in addiction treatment programs is essential to reduce the risk of relapse, and providing access to resources like methadone or buprenorphine treatment, as well as support groups like Narcotics Anonymous, can significantly aid in this effort. Teaching patients the proper aseptic techniques for managing intravenous lines, central venous catheters, and other medical devices is also key in preventing healthcare-associated infections. Additionally, prophylactic antibiotics may be indicated for high-risk individuals undergoing invasive procedures or surgeries to reduce the risk of IE, and ensuring appropriate follow-up care with cardiology and infectious disease specialists is vital for monitoring for early signs of recurrence or complications.

Patient education plays an equally important role in the management of TVIE. Patients should be made aware of the early signs and symptoms of TVIE, such as fever, fatigue, chest pain, cough, and shortness of breath, to ensure prompt treatment and prevent complications. Emphasizing the importance of completing the entire course of prescribed antibiotics, even if they feel better before finishing the regimen, helps prevent antibiotic resistance and relapse.

Lifestyle modifications such as maintaining good hygiene, quitting smoking, and avoiding substance use can reduce infection risk and improve overall health. Educating patients on managing comorbidities like diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or heart disease is also crucial, as these conditions can exacerbate the risk of IE. Overall, combining comprehensive deterrence strategies and thorough patient education can minimize the risk of recurrence and improve long-term outcomes for those affected by TVIE.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective TVIE management requires a collaborative, team-based approach involving clinicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals to ensure optimal patient outcomes, safety, and care coordination. Clinicians are central in diagnosing and initiating treatment, utilizing evidence-based guidelines to start empiric antibiotic therapy, and deciding on surgical interventions when needed. Nurses are critical in monitoring the patient's clinical status, managing symptoms, and educating the patient and family about the disease, treatment plan, and lifestyle modifications. Pharmacists contribute by ensuring the correct administration of antibiotics, monitoring drug interactions, and advising on appropriate dosing adjustments, especially in patients with renal dysfunction or complex comorbidities.

Interprofessional communication is essential for enhancing patient-centered care, as timely and accurate information exchange between team members ensures coordinated care and minimizes the risk of complications. For example, when treating TVIE, clear communication between the medical team and the pharmacy regarding the choice of antibiotics, the patient's renal function, and potential drug interactions is crucial. Regular multidisciplinary rounds, where all team members discuss the patient's progress, concerns, and next steps, help align care plans and address emerging issues. Care coordination is critical in managing patients with TVIE, as the disease often involves complex, multisystem complications. By fostering a collaborative, patient-centered approach, the healthcare team can improve outcomes, reduce hospital readmissions, enhance patient safety, and improve overall team performance in managing TVIE.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Hussain ST, Witten J, Shrestha NK, Blackstone EH, Pettersson GB. Tricuspid valve endocarditis. Annals of cardiothoracic surgery. 2017 May:6(3):255-261. doi: 10.21037/acs.2017.03.09. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28706868]

Wurcel AG, Anderson JE, Chui KK, Skinner S, Knox TA, Snydman DR, Stopka TJ. Increasing Infectious Endocarditis Admissions Among Young People Who Inject Drugs. Open forum infectious diseases. 2016 Sep:3(3):ofw157 [PubMed PMID: 27800528]

Chambers HF, Korzeniowski OM, Sande MA. Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis: clinical manifestations in addicts and nonaddicts. Medicine. 1983 May:62(3):170-7 [PubMed PMID: 6843356]

Rasmussen RV, Høst U, Arpi M, Hassager C, Johansen HK, Korup E, Schønheyder HC, Berning J, Gill S, Rosenvinge FS, Fowler VG Jr, Møller JE, Skov RL, Larsen CT, Hansen TF, Mard S, Smit J, Andersen PS, Bruun NE. Prevalence of infective endocarditis in patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia: the value of screening with echocardiography. European journal of echocardiography : the journal of the Working Group on Echocardiography of the European Society of Cardiology. 2011 Jun:12(6):414-20. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jer023. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21685200]

Ruiz ME, Guerrero IC, Tuazon CU. Endocarditis caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: treatment failure with linezolid. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2002 Oct 15:35(8):1018-20 [PubMed PMID: 12355391]

Joseph JP, Meddows TR, Webster DP, Newton JD, Myerson SG, Prendergast B, Scarborough M, Herring N. Prioritizing echocardiography in Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2013 Feb:68(2):444-9. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks408. Epub 2012 Oct 30 [PubMed PMID: 23111851]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePetti CA, Fowler VG Jr. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and endocarditis. Infectious disease clinics of North America. 2002 Jun:16(2):413-35, x-xi [PubMed PMID: 12092480]

Anderson DJ, Murdoch DR, Sexton DJ, Reller LB, Stout JE, Cabell CH, Corey GR. Risk factors for infective endocarditis in patients with enterococcal bacteremia: a case-control study. Infection. 2004 Apr:32(2):72-7 [PubMed PMID: 15057570]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDurack DT, Lukes AS, Bright DK. New criteria for diagnosis of infective endocarditis: utilization of specific echocardiographic findings. Duke Endocarditis Service. The American journal of medicine. 1994 Mar:96(3):200-9 [PubMed PMID: 8154507]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFruauff AA, Barasch ES, Rosenthal A. Solitary myeloblastoma presenting as acute hydrocephalus: review of literature, implications for therapy. Pediatric radiology. 1988:18(5):369-72 [PubMed PMID: 3050842]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHansen JB, Jagt T, Gundtoft P, Sorensen HR. Pharyngo-oesophageal diverticula. A clinical and cineradiographic follow-up study of 23 cases treated by diverticulectomy. Scandinavian journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 1973:7(1):81-6 [PubMed PMID: 4632890]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDinubile MJ. Heart block during bacterial endocarditis: a review of the literature and guidelines for surgical intervention. The American journal of the medical sciences. 1984 May-Jun:287(3):30-2 [PubMed PMID: 6731477]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDe Castro S, Cartoni D, d'Amati G, Beni S, Yao J, Fiorell M, Gallo P, Fedele F, Pandian NG. Diagnostic accuracy of transthoracic and multiplane transesophageal echocardiography for valvular perforation in acute infective endocarditis: correlation with anatomic findings. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2000 May:30(5):825-6 [PubMed PMID: 10816155]

Gould FK, Denning DW, Elliott TS, Foweraker J, Perry JD, Prendergast BD, Sandoe JA, Spry MJ, Watkin RW, Working Party of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. Guidelines for the diagnosis and antibiotic treatment of endocarditis in adults: a report of the Working Party of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2012 Feb:67(2):269-89. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr450. Epub 2011 Nov 14 [PubMed PMID: 22086858]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTorres-Tortosa M, de Cueto M, Vergara A, Sánchez-Porto A, Pérez-Guzmán E, González-Serrano M, Canueto J. Prospective evaluation of a two-week course of intravenous antibiotics in intravenous drug addicts with infective endocarditis. Grupo de Estudio de Enfermedades Infecciosas de la Provincia de Cádiz. European journal of clinical microbiology & infectious diseases : official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology. 1994 Jul:13(7):559-64 [PubMed PMID: 7805683]

Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP 3rd, Guyton RA, O'Gara PT, Ruiz CE, Skubas NJ, Sorajja P, Sundt TM 3rd, Thomas JD, ACC/AHA Task Force Members. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014 Jun 10:129(23):2440-92. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000029. Epub 2014 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 24589852]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceOrtiz-Bautista C, López J, García-Granja PE, Sevilla T, Vilacosta I, Sarriá C, Olmos C, Ferrera C, Sáez C, Gómez I, San Román JA. Current profile of infective endocarditis in intravenous drug users: The prognostic relevance of the valves involved. International journal of cardiology. 2015:187():472-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.03.368. Epub 2015 Mar 27 [PubMed PMID: 25846656]

Martín-Dávila P, Navas E, Fortún J, Moya JL, Cobo J, Pintado V, Quereda C, Jiménez-Mena M, Moreno S. Analysis of mortality and risk factors associated with native valve endocarditis in drug users: the importance of vegetation size. American heart journal. 2005 Nov:150(5):1099-106 [PubMed PMID: 16291005]

Mocchegiani R, Nataloni M. Complications of infective endocarditis. Cardiovascular & hematological disorders drug targets. 2009 Dec:9(4):240-8 [PubMed PMID: 19751182]