Introduction

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) is a member of the Alphaherpesviridae subfamily. Its structure is composed of linear dsDNA, an icosahedral capsid that is 100 to 110 nm in diameter, with a spikey envelope. In general, the pathogenesis of HSV-1 infection follows a cycle of primary infection of epithelial cells, latency primarily in neurons, and reactivation. HSV-1 is responsible for establishing primary and recurrent vesicular eruptions, primarily in the orolabial and genital mucosa. HSV-1 infection has a wide variety of presentations, including orolabial herpes, herpetic sycosis (HSV folliculitis), herpes gladiatorum, herpetic whitlow, ocular HSV infection, herpes encephalitis, Kaposi varicelliform eruption (eczema herpeticum), and severe or chronic HSV infection. Antiviral therapy limits the course of HSV infection.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Risk factors for HSV-1 infection differ depending on the type of HSV-1 infection. In the case of orolabial herpes, risk factors include any activity that exposes one to an infected patient’s saliva, for example, shared drinkware or cosmetics, or mouth to mouth contact.

The major risk factor for herpetic sycosis is close shaving with a razor blade in the presence of an acute orolabial infection.

Risk factors for herpes gladiatorum include participation in high-contact sports such as rugby, wrestling, MMA, and boxing.

Risk factors for herpetic whitlow include thumb sucking and nail biting in the presence of orolabial HSV-1 infection in the child population, and medical/dental profession in the adult population (although HSV-2 most commonly causes herpetic whitlow in adults).

A major risk factor for herpes encephalitis is mutations in the toll-like receptor (TLR-3) or UNC-93B genes. It has been postulated that these mutations inhibit normal interferon-based responses.

The major risk factor for eczema herpeticum is skin barrier dysfunction. This can be seen in atopic dermatitis, Darier disease, Hailey-Hailey disease, mycosis fungoides, and all types of ichthyosis. The increased risk is also associated with mutations in the filaggrin gene, which is seen in atopic dermatitis and ichthyosis vulgaris. Pharmaceutical risk factors for eczema herpeticum include the use of topical calcineurin inhibitors such as pimecrolimus and tacrolimus.

Risk factors for severe or chronic HSV infection include immunocompromised states such as transplant recipients (solid organ or hematopoietic stem cells), HIV infection, or leukemia/lymphoma patients.[4][5]

Epidemiology

It has been hypothesized that approximately one-third of the world’s population has experienced symptomatic HSV-1 at some point throughout his or her lifetime. HSV-1 first establishes primary infection in patients with no existing antibodies to HSV-1 or HSV-2. Non-primary initial infection is defined as infection with one HSV subtype in patients who already have antibodies to the other HSV type (i.e., HSV-1 infection in a patient with HSV-2 antibodies, or vice versa). Reactivation results in recurrent infection and most commonly presents as asymptomatic viral shedding.

Approximately 1 in 1000 newborns in the United States experience a neonatal herpes simplex virus infection, resulting from HSV exposure during vaginal delivery. Women with recurrent genital herpes have a low risk of vertically transmitting HSV to their neonate. However, women who acquire a genital HSV infection during pregnancy have a higher risk.

Epidemiologically, it is important to note that herpes encephalitis is the leading cause of lethal encephalitis in the United States, and ocular HSV infection is a common cause of blindness in the United States.[6][7][8][9][10]

Pathophysiology

HSV-1 is typically spread through direct contact with contaminated saliva or other infected bodily secretions, as opposed to HSV-2, which is spread primarily by sexual contact. HSV-1 begins to replicate at the site of infection (mucocutaneous) and then proceeds to travel by retrograde flow down an axon to the dorsal root ganglia (DRG). It is in the DRG that latency is established. This latency period allows the virus to remain in a non-infectious state for a variable amount of time before reactivation. HSV-1 is sly in its ability to evade the immune system via several mechanisms. One such mechanism is inducing an intercellular accumulation of CD1d molecules in antigen presenting cells. Normally, these CD1d molecules are transported to the cell surface, where the antigen is presented resulting in the stimulation of natural killer T-cells, thus promoting immune response. When CD1d molecules are sequestered intercellularly, the immune response is inhibited. HSV-1 has several other mechanisms by which it down-regulates various immunologic cells and cytokines.[11][12][13][14][15][16]

Histopathology

Classic, though not pathognomonic, histologic findings for HSV infection include ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Multinucleated keratinocytes may contain Cowdry A inclusions, which are eosinophilic nuclear inclusions that can also be seen in other herpesviruses such as varicella-zoster virus (VZV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV). There is no pathognomonic histologic finding for HSV-1 infection, and therefore, clinical correlation is crucial during histopathologic evaluation.[12]

History and Physical

It is important to note that HSV-1 infection is frequently asymptomatic. When symptoms do occur, there is a wide range of clinical presentations including orolabial herpes, herpetic sycosis (HSV folliculitis), herpes gladiatorum, herpetic whitlow, ocular HSV infection, herpes encephalitis, Kaposi varicelliform eruption (eczema herpeticum), and severe or chronic HSV-1 infection.

HSV-1 is the most common culprit of orolabial herpes (a small percent of cases are attributed to HSV-2). It is important to note that orolabial HSV-1 infection is most commonly asymptomatic. When there are symptoms, the most common manifestation is the “cold sore” or fever blister. In children, symptomatic orolabial HSV-1 infections often present as gingivostomatitis that leads to pain, halitosis, and dysphagia. In adults, it can present as pharyngitis and a mononucleosis-like syndrome.[17]

Symptoms of a primary orolabial infection occur between three days and one week after the exposure. Patients will often experience a viral prodrome consisting of malaise, anorexia, fevers, tender lymphadenopathy, localized pain, tenderness, burning, or tingling prior to the onset of mucocutaneous lesions. Primary HSV-1 lesions usually occur on the mouth and lips. Patients will then demonstrate painful grouped vesicles on an erythematous base. These vesicles exhibit a characteristic scalloped border. These vesicles may then progress to pustules, erosions, and ulcerations. Within 2 to 6 weeks, the lesions crust over and symptoms resolve.[18]

Symptoms of recurrent orolabial infection are typically milder than those of primary infection, with a 24-hour prodrome of tingling, burning, and itch. Recurrent orolabial HSV-1 infections classically affect the vermillion border of the lip (as opposed to the mouth and lips as seen in primary infection).[19]

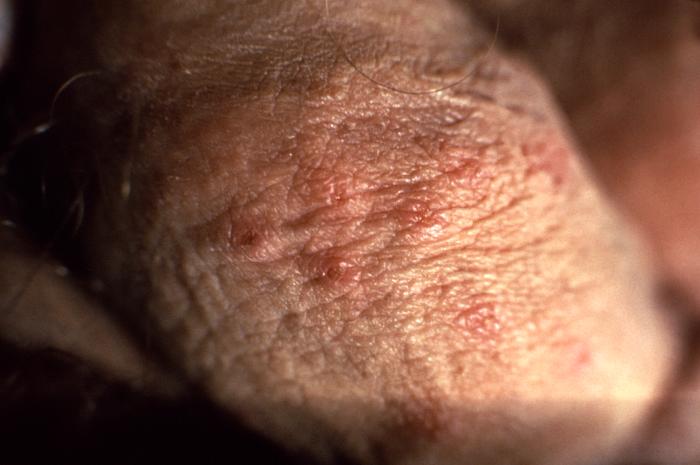

Initial or recurrent HSV-1 infections may affect the hair follicle, and when this occurs, it is termed herpetic sycosis (HSV folliculitis). This will present on the beard area of a male with a history of close razor blade shaving. Lesions exist on a spectrum ranging from scattered follicular papules with erosion to large lesions involving the entire beard area. Herpetic sycosis is self-limited, with a resolution of eroded papules within 2 to 3 weeks.

Lesions of herpes gladiatorum will be seen on the lateral neck, side of the face, and forearms within 4 to 11 days after exposure. A high suspicion for this diagnosis is crucial in athletes, as this is commonly misdiagnosed as bacterial folliculitis.

HSV-1 infection can also occur on the digits or periungual, causing herpetic whitlow. Herpetic whitlow presents as deep blisters that may secondarily erode. A common misdiagnosis is an acute paronychia or blistering dactylitis. Herpetic whitlow can also lead to lymphadenopathy of the epitrochlear or axillary lymph nodes in association with lymphatic streaking, mimicking bacterial cellulitis.

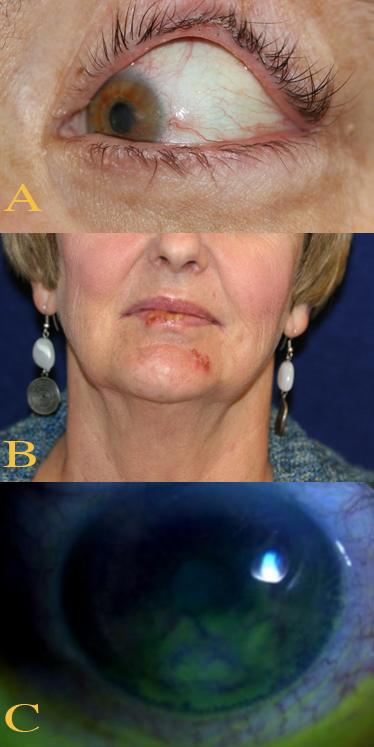

HSV-1 infection of the eye leads to ocular HSV in children and adults. Primary ocular HSV presents with keratoconjunctivitis that can be unilateral or bilateral. There can be associated eyelid tearing, edema, photophobia, chemosis (swelling of the conjunctiva), and preauricular lymphadenopathy. It is common for patients to experience recurrence, and in these cases, it is usually unilateral. Ocular HSV is a common cause of blindness in the United States when it manifests as keratitis or a branching dendritic corneal ulcer (which is pathognomonic for ocular HSV).

Herpes encephalitis is a severe, typically fatal (mortality is greater than 70% if untreated) infection caused by HSV-1. It primarily affects the temporal lobe of the brain leading to bizarre behavior and focal neurological deficits localized to the temporal lobe. Patients may have a fever and altered mental status as well.

Kaposi varicelliform eruption, or eczema herpeticum, presents as an extensive spreading of HSV infection in the setting of a compromised skin barrier (e.g., atopic dermatitis, Darier disease, pemphigus foliaceous, pemphigus vulgaris, Hailey-Hailey disease, mycosis fungoides, ichthyosis). Patients will display 2 to 3 mm punched-out erosions with hemorrhagic crusts in widespread distribution. There may be secondary impetigo with Staphylococcus or Streptococcus species.

Neonatal herpes virus presents at day 5 to 14 of life and favors the scalp and the trunk. It may present with disseminated cutaneous lesions and involvement of oral and ocular mucosa. Central nervous system (CNS) involvement may occur and manifest as encephalitis with lethargy, poor feeding, bulging fontanelle, irritability, and seizures.

In the immunocompromised patient population, HSV infection can result in severe and chronic infection. The most common presentation of severe and chronic HSV infection is quickly enlarging ulcerations or verrucous/pustular lesions. It is not uncommon for patients to have respiratory or gastrointestinal tract involvement and present with dyspnea or dysphagia.[20][21][22][23][24]

Evaluation

The gold standard for diagnosing HSV-1 infection is HSV-1 serology (antibody detection via western blot). The most sensitive and specific mechanism is viral polymerase chain reaction (PCR). However, serology remains the gold standard. Viral culture, direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) assay, and Tzanck smear are alternative methods of diagnosing. It is important to note that the Tzanck smear identifies multinucleated giant cells, so it cannot distinguish between HSV and VZV. The DFA assay, however, can distinguish between the 2 entities.[14]

Treatment / Management

For the treatment of orolabial herpes, the current recommendation is oral valacyclovir (2 grams twice daily for one day). If the patient has frequent outbreaks, chronic suppression is warranted. For chronic suppression of immunocompetent patients, oral valacyclovir 500 mg daily (for patients with less than ten outbreaks per year) or oral valacyclovir 1 gram by mouth daily (for patients with greater than 10 outbreaks a year) is recommended.

For the treatment of eczema herpeticum, it is recommended to use 10 to 14 days of either acyclovir (15 mg/kg with a 400 mg maximum) 3 to 5 times daily or Valacyclovir 1 gram by mouth twice a day.

For immunocompromised patients with severe and chronic HSV, treatment is aimed at chronic suppression. For chronic suppression of immunocompromised patients, oral acyclovir 400 to 800 2 to 3 times daily, or oral valacyclovir 500 mg twice daily is recommended.[25][26][27][28](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of orolabial HSV-1 infection includes aphthous stomatitis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, erythema multiforme (EM) major, and herpangina. These entities can be distinguished from orolabial herpes by history and physical exam findings. The differential diagnosis of herpetic whitlow includes blistering dactylitis and acute or chronic paronychia.

Prognosis

Overall, the vast majority of HSV-1 infections are asymptomatic, and if symptomatic present with mild recurrent mucocutaneous lesions. The prognosis of HSV-1 infection varies depending on the manifestation and location of the HSV-1 infection. The majority of the time, HSV-1 infection follows a chronic course of latency and reactivation. HSV encephalitis is associated with high mortality; approximately 70% of untreated cases are ultimately fatal. The prognosis of ocular HSV can also be grim if the patient develops globe rupture or corneal scarring, as these processes can ultimately lead to blindness.[29]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Herpes type 1 infections are best managed by an interprofessional team that includes the primary provider, pediatrician, nurse practitioner, infectious disease specialist and the internist. The key to treatment is starting the antiviral within 24 hours of symptoms. It is important to understand that most infections spontaneously subside on their own and delayed treatment has no impact on duration or severity of symptoms. During the infection, the patient should be educated on washing hands and avoiding close contact with others.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Ocular and Perioral Involvement in Herpes Simplex Virus Infection. Various clinical findings of herpetic keratitis are demonstrated. In image A (top), herpetic keratitis with neovascularization of the cornea is noted. In image B (middle), HSV type 1 lesions are seen on the patient's lips and chin. Image C (bottom) demonstrates findings of stage 1 neurotrophic keratitis, including fluorescein epithelial staining with Gaule spots, which are scattered areas of dried epithelium.

Contributed by BCK Patel, MD, FRCS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

This image depicts a close view of a patient’s penile shaft, highlighting the presence of a crop of erythematous vesiculopapular lesions, which were determined to have been caused by a herpes genitalis outbreak. Genital herpes is a sexually transmitted disease caused by the herpes simplex viruses type-1 (HSV-1), and type-2 (HSV-2), however, most genital herpes is caused by HSV-2. Symptoms typically include one or more blisters on or around the genitals or rectum. Contributed from the CDC/ Susan Lindsley (Public Domain)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Rechenchoski DZ, Faccin-Galhardi LC, Linhares REC, Nozawa C. Herpesvirus: an underestimated virus. Folia microbiologica. 2017 Mar:62(2):151-156. doi: 10.1007/s12223-016-0482-7. Epub 2016 Nov 17 [PubMed PMID: 27858281]

Soriano V, Romero JD. Rebound in Sexually Transmitted Infections Following the Success of Antiretrovirals for HIV/AIDS. AIDS reviews. 2018:20(4):187-204. doi: 10.24875/AIDSRev.18000034. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30548023]

Mostafa HH, Thompson TW, Konen AJ, Haenchen SD, Hilliard JG, Macdonald SJ, Morrison LA, Davido DJ. Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Mutant with Point Mutations in UL39 Is Impaired for Acute Viral Replication in Mice, Establishment of Latency, and Explant-Induced Reactivation. Journal of virology. 2018 Apr 1:92(7):. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01654-17. Epub 2018 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 29321311]

Pfaff F, Groth M, Sauerbrei A, Zell R. Genotyping of herpes simplex virus type 1 by whole-genome sequencing. The Journal of general virology. 2016 Oct:97(10):2732-2741. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000589. Epub 2016 Aug 24 [PubMed PMID: 27558891]

van Oeffelen L, Biekram M, Poeran J, Hukkelhoven C, Galjaard S, van der Meijden W, Op de Coul E. Update on Neonatal Herpes Simplex Epidemiology in the Netherlands: A Health Problem of Increasing Concern? The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2018 Aug:37(8):806-813. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001905. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29356762]

Chaabane S, Harfouche M, Chemaitelly H, Schwarzer G, Abu-Raddad LJ. Herpes simplex virus type 1 epidemiology in the Middle East and North Africa: systematic review, meta-analyses, and meta-regressions. Scientific reports. 2019 Feb 4:9(1):1136. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37833-8. Epub 2019 Feb 4 [PubMed PMID: 30718696]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFedoreyev SA, Krylova NV, Mishchenko NP, Vasileva EA, Pislyagin EA, Iunikhina OV, Lavrov VF, Svitich OA, Ebralidze LK, Leonova GN. Antiviral and Antioxidant Properties of Echinochrome A. Marine drugs. 2018 Dec 15:16(12):. doi: 10.3390/md16120509. Epub 2018 Dec 15 [PubMed PMID: 30558297]

Jiang Y, Leib D. Preventing neonatal herpes infections through maternal immunization. Future virology. 2017 Dec:12(12):709-711. doi: 10.2217/fvl-2017-0105. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29339967]

Marchi S, Trombetta CM, Gasparini R, Temperton N, Montomoli E. Epidemiology of herpes simplex virus type 1 and 2 in Italy: a seroprevalence study from 2000 to 2014. Journal of preventive medicine and hygiene. 2017 Mar:58(1):E27-E33 [PubMed PMID: 28515628]

Finger-Jardim F, Avila EC, da Hora VP, Gonçalves CV, de Martinez AMB, Soares MA. Prevalence of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 at maternal and fetal sides of the placenta in asymptomatic pregnant women. American journal of reproductive immunology (New York, N.Y. : 1989). 2017 Jul:78(1):. doi: 10.1111/aji.12689. Epub 2017 Apr 25 [PubMed PMID: 28440579]

Rosenberg J, Galen BT. Recurrent Meningitis. Current pain and headache reports. 2017 Jul:21(7):33. doi: 10.1007/s11916-017-0635-7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28551737]

Cruz AT, Freedman SB, Kulik DM, Okada PJ, Fleming AH, Mistry RD, Thomson JE, Schnadower D, Arms JL, Mahajan P, Garro AC, Pruitt CM, Balamuth F, Uspal NG, Aronson PL, Lyons TW, Thompson AD, Curtis SJ, Ishimine PT, Schmidt SM, Bradin SA, Grether-Jones KL, Miller AS, Louie J, Shah SS, Nigrovic LE, HSV Study Group of the Pediatric Emergency Medicine Collaborative Research Committee. Herpes Simplex Virus Infection in Infants Undergoing Meningitis Evaluation. Pediatrics. 2018 Feb:141(2):. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1688. Epub 2018 Jan 3 [PubMed PMID: 29298827]

Zhang J, Liu H, Wei B. Immune response of T cells during herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) infection. Journal of Zhejiang University. Science. B. 2017 Apr.:18(4):277-288. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1600460. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28378566]

Giraldo D, Wilcox DR, Longnecker R. The Type I Interferon Response and Age-Dependent Susceptibility to Herpes Simplex Virus Infection. DNA and cell biology. 2017 May:36(5):329-334. doi: 10.1089/dna.2017.3668. Epub 2017 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 28278385]

Rajasagi NK, Rouse BT. Application of our understanding of pathogenesis of herpetic stromal keratitis for novel therapy. Microbes and infection. 2018 Oct-Nov:20(9-10):526-530. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2017.12.014. Epub 2018 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 29329934]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBin L, Li X, Richers B, Streib JE, Hu JW, Taylor P, Leung DYM. Ankyrin repeat domain 1 regulates innate immune responses against herpes simplex virus 1: A potential role in eczema herpeticum. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2018 Jun:141(6):2085-2093.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.01.001. Epub 2018 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 29371118]

Darji K, Frisch S, Adjei Boakye E, Siegfried E. Characterization of children with recurrent eczema herpeticum and response to treatment with interferon-gamma. Pediatric dermatology. 2017 Nov:34(6):686-689. doi: 10.1111/pde.13301. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29144049]

Wei EY, Coghlin DT. Beyond Folliculitis: Recognizing Herpes Gladiatorum in Adolescent Athletes. The Journal of pediatrics. 2017 Nov:190():283. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.06.062. Epub 2017 Jul 17 [PubMed PMID: 28728810]

Williams C, Wells J, Klein R, Sylvester T, Sunenshine R, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Notes from the field: outbreak of skin lesions among high school wrestlers--Arizona, 2014. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2015 May 29:64(20):559-60 [PubMed PMID: 26020140]

Kolawole OM, Amuda OO, Nzurumike C, Suleiman MM, Ikhevha Ogah J. Seroprevalence and Co-Infection of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) Among Pregnant Women in Lokoja, North-Central Nigeria. Iranian Red Crescent medical journal. 2016 Oct:18(10):e25284. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.25284. Epub 2016 Aug 10 [PubMed PMID: 28180012]

El Hayderi L, Rübben A, Nikkels AF. The alpha-herpesviridae in dermatology : Herpes simplex virus types I and II. Der Hautarzt; Zeitschrift fur Dermatologie, Venerologie, und verwandte Gebiete. 2017 Dec:68(Suppl 1):1-5. doi: 10.1007/s00105-016-3919-7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28197698]

Shenoy R, Mostow E, Cain G. Eczema herpeticum in a wrestler. Clinical journal of sport medicine : official journal of the Canadian Academy of Sport Medicine. 2015 Jan:25(1):e18-9. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000097. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24714395]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLi Z, Breitwieser FP, Lu J, Jun AS, Asnaghi L, Salzberg SL, Eberhart CG. Identifying Corneal Infections in Formalin-Fixed Specimens Using Next Generation Sequencing. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2018 Jan 1:59(1):280-288. doi: 10.1167/iovs.17-21617. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29340642]

El Hayderi L, Rübben A, Nikkels AF. [The alpha-herpesviridae in dermatology : Herpes simplex virus types I and II. German version]. Der Hautarzt; Zeitschrift fur Dermatologie, Venerologie, und verwandte Gebiete. 2017 Mar:68(3):181-186. doi: 10.1007/s00105-016-3929-5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28197699]

Sanders JE, Garcia SE. Pediatric herpes simplex virus infections: an evidence-based approach to treatment. Pediatric emergency medicine practice. 2014 Jan:11(1):1-19; quiz 19 [PubMed PMID: 24649621]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKalogeropoulos D, Geka A, Malamos K, Kanari M, Kalogeropoulos C. New Therapeutic Perceptions in a Patient with Complicated Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Keratitis: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. The American journal of case reports. 2017 Dec 27:18():1382-1389 [PubMed PMID: 29279602]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAnderson BJ, McGuire DP, Reed M, Foster M, Ortiz D. Prophylactic Valacyclovir to Prevent Outbreaks of Primary Herpes Gladiatorum at a 28-Day Wrestling Camp: A 10-Year Review. Clinical journal of sport medicine : official journal of the Canadian Academy of Sport Medicine. 2016 Jul:26(4):272-8. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000255. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26540599]

Mir-Bonafé JM, Román-Curto C, Santos-Briz A, Palacios-Álvarez I, Santos-Durán JC, Fernández-López E. Eczema herpeticum with herpetic folliculitis after bone marrow transplant under prophylactic acyclovir: are patients with underlying dermatologic disorders at higher risk? Transplant infectious disease : an official journal of the Transplantation Society. 2013 Apr:15(2):E75-80. doi: 10.1111/tid.12058. Epub 2013 Feb 6 [PubMed PMID: 23387866]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGottlieb SL, Giersing BK, Hickling J, Jones R, Deal C, Kaslow DC, HSV Vaccine Expert Consultation Group. Meeting report: Initial World Health Organization consultation on herpes simplex virus (HSV) vaccine preferred product characteristics, March 2017. Vaccine. 2019 Nov 28:37(50):7408-7418. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.10.084. Epub 2017 Dec 8 [PubMed PMID: 29224963]