Introduction

Obesity in the United States has been increasing at an alarming rate in the past 50 years, and presently over 98.7 million US residents are affected. In 2014, obesity and its related co-morbidities accounted for 14.3% of U.S. heal care expenditure.[1] Weight loss surgery is considered a safe and durable treatment option for obesity. The applied techniques have been continually evolving and yielding better outcomes.

Sleeve gastrectomy, one of the most popular bariatric surgeries in the modern era, was first performed in 1990 as the first of a two-stage operation for biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS). The first laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy was performed in 1999. The original indication for a sleeve gastrectomy was in patients with super obesity (BMI>60) to induce weight loss to more safely undergo the second stage BPD-DS.[2] While following these patients, it was noted that they were having excellent reductions in excess body weight and in 2008 the indications for laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) were published.[3] When compared to other weight-loss surgeries, sleeve gastrectomy is technically easier with relatively less morbidity and thus has become the most common weight loss surgery performed in the United States.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

In order to understand and perform a sleeve gastrectomy, you must understand the anatomy of the stomach, its surrounding structures, and the vast bloody supply from the superior mesenteric artery and celiac trunk.

General

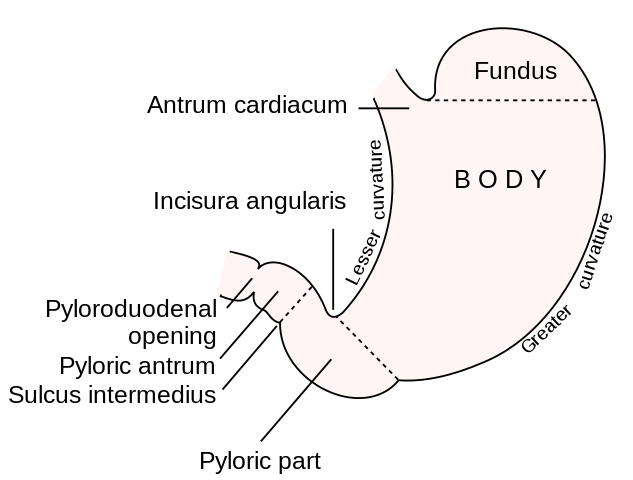

The stomach is a muscular tube that begins at the diaphragmatic hiatus, the lower esophageal sphincter, and ends as it continues as the 1st portion of the duodenum. It is divided into the cardia (just distal to GE junction), fundus (abutting the left diaphragm), body, antrum, and pylorus (most distal portion entering the duodenum.) The lesser curvature lies beneath the medial segments of the liver and includes the incisura angularis which can be identified as the junction of the vertical and horizontal axes of the lesser curvature (marks the transition of the body to antrum). The greater curvature is the long left lateral border of the stomach from the fundus to the pylorus which is connected to the greater omentum. The left border of the intraabdominal esophagus and the fundus meet at an acute angle termed the “angle of His.” Posterior to the stomach lies the lesser sac which is a potential space anterior to the pancreas and bordered by the splenic artery, spleen, left kidney, and transverse mesocolon.

Ligaments

Gastrohepatic ligament - lesser curvature to the medial liver edge, contains the left and right gastric arteries. It may contain a replaced left hepatic artery

Gastrophrenic ligament - fundus to left hemidiaphragm

Gastrosplenic ligament - greater curvature to the spleen (which lies in the left upper quadrant) and contains the short gastric vessels

Gastrocolic ligament - inferior stomach to the transverse colon, considered part of the greater omentum and contained the gastroepiploic vessels

Blood Supply

The celiac trunk has three branches; left gastric, common hepatic, and splenic arteries. The left gastric artery runs along the superior lesser curvature and anastomoses with the right gastric artery. The left gastric artery is the principal blood supply to the stomach after sleeve gastrectomy and it gives off many posterior branches which should remain uninterrupted during dissection of the posterior surface of the stomach. The common hepatic artery gives off the gastroduodenal artery which runs behind the first portion of the duodenum. The right gastric artery is a branch of the proper hepatic artery and joins the left gastric artery along the lesser curvature. The right gastroepiploic artery then branches from the gastroduodenal artery and runs in the gastrocolic ligament along the greater curvature to join the left gastroepiploic artery which is a branch of the splenic artery coursing along the greater curvature from lateral to medial. The splenic artery also gives off 3-5 short gastric arteries running in the gastrosplenic ligament to the gastric fundus.

Indications

The indications for sleeve gastrectomy are mainly for bariatric procedures. The classic criteria for a patient to be a candidate for any bariatric surgery are: [4]

1) BMI greater than or equal to 40 or BMI greater than or equal to 35 with at least one obesity-related comorbid conditions (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or severely limiting musculoskeletal issues)

2) Unsuccessful nonoperative weight loss attempts

3) Mental health clearance

4) No medical contraindication to surgery

Recent updates have included patients with a BMI of 30-35 with uncontrollable type 2 diabetes or metabolic syndrome as an indication for a laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy.[5]

Contraindications

Absolute contraindications include the inability to tolerate general anesthesia, uncontrollable coagulopathy, and a severe psychiatric illness.

Relative contraindications are Barrett esophagus and severe gastroesophageal reflux disease.[6]

Equipment

The basic laparoscopic equipment is required for this operation which will include insufflation with CO2 gas, surgical drapes, monitors, laparoscopic instruments, electrocautery, and trocars. Contrary to conventional laparoscopic procedures, with bariatric patients, you will require longer trocars as well as longer laparoscopic instruments to accommodate for the thicker abdominal wall.

Also required are:

- Three 5 mm trocars and one 15 mm trocar.

- A liver retractor.

- 5 mm 30-degree angled laparoscope

- Endoscopic linear stapler

- 32-40 French bougie

- Flexible endoscope

- Laparoscopic energy device[7]

Personnel

For bariatric surgery, the patient is required to be evaluated by an interprofessional team before being a surgical candidate. This includes a nutritionist, a psychiatric specialist, a surgical team, and a primary care physician.

For the operative portion, the following personnel is required; an anesthesiologist, experienced metabolic surgeon, scrub nurse, and first assistant.

Preparation

Morbid obesity in women can have many implications. It can lead to irregular menstrual cycles and infertility. Also, morbidly obese women are at increased risk of developing many obstetric complications such as gestational diabetes, pregnancy-induced hypertension/preeclampsia, and anesthesia-associated complications. Large for gestational age fetuses are more common in morbidly obese women. Many clinical practice guidelines, including guidelines from the American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS), recommend avoiding pregnancy before, and at least 12-18 months after bariatric surgery. The main concern of pregnancy in the immediate early postoperative period after bariatric surgery is the developing fetus could be affected by rapid weight loss and potential micronutrient deficiencies. Rapid weight loss with resulting malnutrition can affect the mother as well.[8][9][10]

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends using nonoral hormonal contraception (e.g., levonorgestrel intrauterine system or implants) for women who undergo bariatric surgery and desire hormonal contraception. Barrier contraception is also helpful in the prevention of sexually transmitted diseases. The physiologic and anatomic changes of bariatric surgery may augment the risk of oral contraceptive failure. Oral contraceptive pills also increase the risk of thromboembolism in obese patients.

Preoperatively all patients should receive upper endoscopy. There is increasing evidence for the use of an “ultra-low” preoperative carbohydrate diet to shrink the liver allowing for better exposure and favorable outcomes.[11]

The patient will be given preoperative antibiotics 30 minutes prior to incision as well as VTE prophylaxis. The hair on the abdomen is removed with clippers in the preoperative area. The patient is placed on the operating table and secured in the supine position with the arms extended. After induction of anesthesia, an orogastric tube is positioned within the stomach.

Technique or Treatment

There are many ways to perform a laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, and an example is provided below. Different techniques and the data to support them will also be discussed in each section.

Entrance and Set Up

Entrance into the abdomen begins in the left upper quadrant, and the technique utilized is at the surgeon's discretion. The abdomen is insufflated to a pressure of 15 mmHg, and the abdomen is visually explored with a laparoscope. Trocar placement will be as follows:

- 5 mm trocar in the left upper quadrant, anterior axillary line (assistant port)

- 5 mm trocar in the left upper paramedian midclavicular line (camera port)

- 5 mm trocar in the right upper paramedic midclavicular line

- 15 mm trocar placed at or just superior and to the right of the umbilicus (should be parallel with the lesser curvature of the stomach)

- Liver retractor placed in the subxiphoid area

- The two 5mm ports on the left side will be used by the assistant, the two right-sided ports (15mm and 5mm right paramedian) will be used by the primary surgeon. Once all ports are in and the liver is retracted, the patient is placed in reverse Trendelenburg.

Mobilization of the Greater Curvature

Dissection begins by dividing the greater omentum 5 cm proximal to the pylorus near the incisor angularis. The gastroepiploic vessels are divided using an energy device along the greater curvature toward the short gastric vessels. Division of the short gastric vessels should be done with a bipolar cautery device. This dissection is continued to completely divide the gastrophrenic ligament and mobilize the angle of His to identify the left crus of the diaphragm.

- Length from the pylorus - there is debate on the starting point for the first staple load in terms of distance from the pylorus. Distances from 2-6cm are practiced today, and the amount of retained antrum determines its clinical significance. With a distance of 2 cm, more antrum is resected, and the gastric remnant is relatively smaller. This, in theory, will produce an increase in excess weight loss but may lead to more complications from the increase in distal intragastric pressure. Studies comparing 2cm distance and 4-6cm distance have shown mixed results. One showed equal outcomes when considering weight loss and complications[12], and the other demonstrated increased weight loss without an increase in complications for the 2cm length.[13] The opinion of the international consensus conference was to start the resection at least 3cm from the pylorus.

Identification and Repair of a Hiatal Hernia

After exposing the left crura of the diaphragm, one should determine if a hiatal hernia is present. If so, it is recommended to reduce the sac and repair the hernia with crural approximation utilizing interrupted sutures posterior to the esophagus.

Posterior Mobilization

The omentum has been separated from the greater curvature allowing access into the lesser sac. The stomach is grasped and lifted anteriorly to expose its posterior wall. All adhesions to the lesser sac are taken down up until the most medial aspect of the stomach at the lesser curvature.

Bougie Placement

The orogastric tube is removed and a 32 to 40 French Bougie is placed under laparoscopic visualization and is directed to a point distal to the divided omental attachments.

- Size of bougie - the thought behind choosing a size of the bougie to create the sleeve gastrectomy around stems on two outcomes, proximal staple line leaks, and percent estimated weight loss. Historically it was shown that with smaller french bougie this would lead to an increase in leak rate and weight loss. A meta-analysis in 2013 has shown that there is a leak rate reduction of 66% when using a bougie of 40 French or higher without a statistically significant alteration in the effectiveness of weight loss.[14] This would suggest a larger size bougie would be beneficial in terms of leaks, but it did not address other complications, and their impact on them, and further studies are needed. In the Fifth International Consensus Conference, it was recommended that a large bougie should be used (median was 36French).[15]

Creation of a Stapled Sleeve Gastrectomy

A 60mm long endoscopic stapler is used for this. Firing is begun at a point approximately 5 cm proximal to the pylorus along the bougie and with an angle that is parallel to the lesser curvature. One must ensure that the stapler encompasses equal lengths of the anterior and posterior stomach to avoid “spiraling” of the sleeve. The staple lines are sequentially fired along the bougie toward the angle of His and divide the fundus at a distance of .5 to 2 cm lateral to the esophagus. The remaining cardia will be inverted at the GE junction utilizing interrupted Lembert sutures. The amputated stomach is then removed through the 15mm port.

- Reinforcement of staple line - the main objectives of support of the staple line are to reduce the staple line leak and hemorrhage rates. There are many techniques to do this and two main categories, oversewing and buttressing. In a recent meta-analysis in 2016, when comparing reinforcement to no reinforcement, there was no statistically significant difference in leak rate; however, it did show a decrease in overall complications, including staple line bleeding. When comparing oversewing to buttressing, sewing revealed weaker benefits with longer operative times and a higher complication rate.[16] There is further research needed to determine the best method of reinforcement, but in the latest consensus, most experts are using a buttress technique.[15]

- Staple height - on average, the wall thickness of the antrum, body, and funds are 3.1, 2.4, and 1.7mm, respectively.[17] The goal is to use a stapler with tall enough staples to accommodate the thicker antrum instead of, the thinner fundus. Some have advocated superior results using taller staple height distally and shortener staple height proximally when approaching the fundus.[18]

Endoscopy

A flexible endoscope is carefully inserted into the esophagus, and the staple line is visualized for integrity and hemostasis. The remaining stomach may be submerged in irrigation fluid and then insufflated with the endoscope to check for a staple line leak.

- Intraoperative leak test - this is up to the surgeons' discretion as it has had inconsistent results. A multicenter retrospective analysis in 2017 demonstrated a poor sensitivity of intraoperative leak test to predict postoperative leaks. They demonstrated that the intraoperative leak test was negative in 91% of patients who eventually developed a staple line leak.[19]

Closure

A fascial closure is done at the 15mm port site, and skin closure is done at all sites.[20]

Complications

Currently, the 30-day morbidity and mortality of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in the literature range from 0-17.5% and 0-1.2%, respectively.[21]

As with many operations, complications can be divided into early and late.

Early

Hemorrhage

The reported incidence is between 1 and 6% postoperatively and can be intraluminal or intraabdominal.[22] Extraluminal bleeding is typically from the staple line, spleen, liver, or abdominal wall. This is treated with reoperation at the surgeon's discretion. For intraluminal bleeding, the patient may present with melena or hematemesis with a concomitant hematocrit drop. This may be treated by endoscopic means and, more rarely, surgical intervention.

There is some evidence to support reinforcement of the staple line to prevent bleeding. There have been more successful outcomes when comparing buttressing materials instead of staple line suture reinforcement. There is still controversy in this area, and a definitive conclusion has not yet been made.[23]

Leak

The incidence of a postoperative leak in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy is between 2 and 3%.[24] The cause of the leak in sleeve gastrectomy patients is increased pressure relayed on the staple line in the setting of relative ischemia. This is typically located just below the GE junction, where there is relative ischemia due to the dependence on the sacrificed short gastric vessels. An increase in pressure may be due to a distal narrowing caused by a small-caliber bougie, stricturing, or technical error of firing the stapler too close to the incisura angularis is. There have been mixed results and opinions on whether staple line reinforcement can decrease postoperative leak rate, and further studies are needed. It has been demonstrated that a larger bougie size will decrease the incidence of leaks in sleeve gastrectomy patients.

Patients may be asymptomatic but frequently present with fever, tachycardia, and tachypnea with elevated heart rate being the first sign. The diagnostic test of choice is a CT scan with oral and IV contrast which demonstrates relatively high sensitivity and specificity. A UGI contrast series has a high specificity, but low sensitivity and thus is not recommended as first-line diagnostic imaging.

Leaks should be classified as either acute (<5 days postoperatively) or chronic (>4 weeks postoperatively). In the acute, unstable patient, exploration with drainage of the leak and placement of a distal feeding tube is the management of choice. In chronic patients, operative management is less successful. If they are unstable, the patient will require an operation as described for an acute leak. For a chronic leak/fistula in a stable patient, treatment is conservative utilizing drainage of abscess if present, antibiotics, NPO, TPN, and endoluminal stenting. Most chronic fistulae/leaks will close within the range of 4 weeks to 3 months.[25]

Late

Stricture

This complication has an incidence of up to 4 percent and may present acutely secondary to edema or more often chronically. The common symptoms are dysphagia, nausea, and vomiting and the most common location is at the incisura angularis. In the acute setting, this is likely secondary to edema or kinking due to technical issues. The diagnostic image of choice is a UGI contrast study. Treatment of the acute stricture is conservative and only requires surgery in the setting of nonresolution. Patients who present with chronic strictures should undergo endoscopic balloon dilations and may require multiple interventions for long-term improvement. Failure of endoscopic management will require surgical intervention with either a laparoscopic seromyotomy or conversion to a gastric bypass procedure.[26]

Gastroesophageal Reflux

Severe GERD is a relative contraindication to sleeve gastrectomy. There have been conflicting results in the literature, but many have advocated the development or worsening of reflux symptoms. First-line therapy is PPIs, but if the patient has severe symptoms and is refractory to medical treatment, they may require conversion to a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.[27]

Nutritional Deficiencies

All bariatric procedures harbor nutrient deficiencies and are largely prevented by routine testing and daily supplementation. There is data to show a decreased incidence of nutrient deficiency when compared to gastric bypass patients with the exception of folate.[27]

If a patient with post-sleeve gastrectomy status presents with the classic triad of Wernicke’s encephalopathy, thiamine deficiency should be evaluated. The triad includes encephalopathy, oculomotor findings (such as nystagmus, ophthalmoplegia), and signs of cerebellar impairment (such as ataxic gait and dysmetria). Patients also can have polyneuropathy. If psychosis and confabulation are present, it is referred to as Wernicke-korsakoff syndrome. The most common manifestation of Wernicke's encephalopathy is altered mental status. Clinicians should have a high index of suspicion. They should proceed with immediate treatment before the results of thiamine assessments are confirmed. After the thiamine administration, patients should be monitored and evaluated vigilantly for the improvement of clinical manifestations.[28][29][30][31]

Clinical Significance

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy has become the most popular weight loss procedure in the United States over the last two decades. Long-term data is now available on the outcomes of sleeve gastrectomy, and it is very promising. The average excess weight loss after five years in a laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy is reported to be around 60%, and the resolution of comorbidities is excellent. A meta-analysis in 2017 compared midterm and long-term results between sleeve gastrectomy and roux-en-y gastric bypass. The conclusion was that in the midterm (3-5 years postoperatively) the two surgeries had similar results in terms of excess weight loss and resolution or improvement of comorbidities. The long-term data demonstrated that gastric bypass eventually did have superior excess weight loss but the improvement in comorbidities remained the same between the two procedures.[32]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Management of obesity is with an interprofessional team to get the ideal results. Even though there are several types of bariatric procedures for weight loss, the key is patient education on the prevention of obesity. All healthcare workers including nurse practitioners should educate the patient on a healthy diet, regular exercise, and maintaining a healthy weight. These preventive measures do work as long as the patient is compliant. More important these measures are virtually devoid of risks. Bariatric surgery does not cure obesity and the results are not always guaranteed. However, for those who do manage to lose weight with surgery, there is an added benefit of better glucose control, lowering of blood pressure and lipids. (Level II)

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

English WJ, DeMaria EJ, Brethauer SA, Mattar SG, Rosenthal RJ, Morton JM. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery estimation of metabolic and bariatric procedures performed in the United States in 2016. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 2018 Mar:14(3):259-263. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2017.12.013. Epub 2017 Dec 16 [PubMed PMID: 29370995]

Topart P, Becouarn G, Ritz P. Should biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch be done as single-stage procedure in patients with BMI } or = 50 kg/m2? Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 2010 Jan-Feb:6(1):59-63. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2009.04.016. Epub 2009 May 13 [PubMed PMID: 19640795]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBellanger DE, Greenway FL. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, 529 cases without a leak: short-term results and technical considerations. Obesity surgery. 2011 Feb:21(2):146-50. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0320-y. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21132397]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChoban PS, Jackson B, Poplawski S, Bistolarides P. Bariatric surgery for morbid obesity: why, who, when, how, where, and then what? Cleveland Clinic journal of medicine. 2002 Nov:69(11):897-903 [PubMed PMID: 12430975]

Mechanick JI, Youdim A, Jones DB, Garvey WT, Hurley DL, McMahon MM, Heinberg LJ, Kushner R, Adams TD, Shikora S, Dixon JB, Brethauer S, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, Obesity Society, American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient--2013 update: cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.). 2013 Mar:21 Suppl 1(0 1):S1-27. doi: 10.1002/oby.20461. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23529939]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFelsenreich DM, Kefurt R, Schermann M, Beckerhinn P, Kristo I, Krebs M, Prager G, Langer FB. Reflux, Sleeve Dilation, and Barrett's Esophagus after Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy: Long-Term Follow-Up. Obesity surgery. 2017 Dec:27(12):3092-3101. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2748-9. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28593484]

Chung AY, Thompson R, Overby DW, Duke MC, Farrell TM. Sleeve Gastrectomy: Surgical Tips. Journal of laparoendoscopic & advanced surgical techniques. Part A. 2018 Aug:28(8):930-937. doi: 10.1089/lap.2018.0392. Epub 2018 Jul 13 [PubMed PMID: 30004814]

Rottenstreich A, Levin G, Ben Porat T, Rottenstreich M, Meyer R, Elazary R. Extremely early pregnancy ({6 mo) after sleeve gastrectomy: maternal and perinatal outcomes. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 2021 Feb:17(2):356-362. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2020.09.025. Epub 2020 Sep 24 [PubMed PMID: 33268326]

Rottenstreich A, Levin G, Kleinstern G, Rottenstreich M, Elchalal U, Elazary R. The effect of surgery-to-conception interval on pregnancy outcomes after sleeve gastrectomy. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 2018 Dec:14(12):1795-1803. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2018.09.485. Epub 2018 Sep 29 [PubMed PMID: 30385070]

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee opinion no. 549: obesity in pregnancy. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2013 Jan:121(1):213-7 [PubMed PMID: 23262963]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKaska L, Proczko M, Stefaniak T, Kobiela J, Sledziński Z. Redesigning the process of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy based on risk analysis resulted in 100 consecutive procedures without complications. Wideochirurgia i inne techniki maloinwazyjne = Videosurgery and other miniinvasive techniques. 2013 Dec:8(4):289-300. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2011.34797. Epub 2013 May 7 [PubMed PMID: 24501598]

ElGeidie A, ElHemaly M, Hamdy E, El Sorogy M, AbdelGawad M, GadElHak N. The effect of residual gastric antrum size on the outcome of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a prospective randomized trial. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 2015 Sep-Oct:11(5):997-1003. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2014.12.025. Epub 2014 Dec 29 [PubMed PMID: 25638594]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAbdallah E, El Nakeeb A, Youssef T, Abdallah H, Ellatif MA, Lotfy A, Youssef M, Elganash A, Moatamed A, Morshed M, Farid M. Impact of extent of antral resection on surgical outcomes of sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity (a prospective randomized study). Obesity surgery. 2014 Oct:24(10):1587-94. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1242-x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24728866]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceYuval JB, Mintz Y, Cohen MJ, Rivkind AI, Elazary R. The effects of bougie caliber on leaks and excess weight loss following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Is there an ideal bougie size? Obesity surgery. 2013 Oct:23(10):1685-91. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-1047-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23912264]

Gagner M, Hutchinson C, Rosenthal R. Fifth International Consensus Conference: current status of sleeve gastrectomy. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 2016 May:12(4):750-756. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.01.022. Epub 2016 Jan 25 [PubMed PMID: 27178618]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWang Z, Dai X, Xie H, Feng J, Li Z, Lu Q. The efficacy of staple line reinforcement during laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. International journal of surgery (London, England). 2016 Jan:25():145-52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.12.007. Epub 2015 Dec 15 [PubMed PMID: 26700201]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceElariny H, González H, Wang B. Tissue thickness of human stomach measured on excised gastric specimens from obese patients. Surgical technology international. 2005:14():119-24 [PubMed PMID: 16525963]

Warner DL, Sasse KC. Technical Details of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy Leading to Lowered Leak Rate: Discussion of 1070 Consecutive Cases. Minimally invasive surgery. 2017:2017():4367059. doi: 10.1155/2017/4367059. Epub 2017 Jul 6 [PubMed PMID: 28761766]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBingham J, Kaufman J, Hata K, Dickerson J, Beekley A, Wisbach G, Swann J, Ahnfeldt E, Hawkins D, Choi Y, Lim R, Martin M. A multicenter study of routine versus selective intraoperative leak testing for sleeve gastrectomy. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 2017 Sep:13(9):1469-1475. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2017.05.022. Epub 2017 May 25 [PubMed PMID: 28629729]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMcGuire MM, Nadler EP, Qureshi FG. Laparoscopic vertical sleeve gastrectomy for adolescents with morbid obesity. Seminars in pediatric surgery. 2014 Feb:23(1):21-3. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2013.10.021. Epub 2013 Nov 1 [PubMed PMID: 24491364]

Ali M, El Chaar M, Ghiassi S, Rogers AM, American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Clinical Issues Committee. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery updated position statement on sleeve gastrectomy as a bariatric procedure. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 2017 Oct:13(10):1652-1657. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2017.08.007. Epub 2017 Aug 22 [PubMed PMID: 29054173]

Frezza EE. Laparoscopic vertical sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity. The future procedure of choice? Surgery today. 2007:37(4):275-81 [PubMed PMID: 17387557]

Diamantis T, Apostolou KG, Alexandrou A, Griniatsos J, Felekouras E, Tsigris C. Review of long-term weight loss results after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 2014 Jan-Feb:10(1):177-83. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2013.11.007. Epub 2013 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 24507083]

Shikora SA, Mahoney CB. Clinical Benefit of Gastric Staple Line Reinforcement (SLR) in Gastrointestinal Surgery: a Meta-analysis. Obesity surgery. 2015 Jul:25(7):1133-41. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1703-x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25968078]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBurgos AM, Braghetto I, Csendes A, Maluenda F, Korn O, Yarmuch J, Gutierrez L. Gastric leak after laparoscopic-sleeve gastrectomy for obesity. Obesity surgery. 2009 Dec:19(12):1672-7. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9884-9. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19506979]

Parikh A, Alley JB, Peterson RM, Harnisch MC, Pfluke JM, Tapper DM, Fenton SJ. Management options for symptomatic stenosis after laparoscopic vertical sleeve gastrectomy in the morbidly obese. Surgical endoscopy. 2012 Mar:26(3):738-46. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1945-1. Epub 2011 Nov 2 [PubMed PMID: 22044967]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGehrer S, Kern B, Peters T, Christoffel-Courtin C, Peterli R. Fewer nutrient deficiencies after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) than after laparoscopic Roux-Y-gastric bypass (LRYGB)-a prospective study. Obesity surgery. 2010 Apr:20(4):447-53. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-0068-4. Epub 2010 Jan 26 [PubMed PMID: 20101473]

Athanasiou A, Spartalis E, Moris D, Alexandrou A, Liakakos T. Sleeve Gastrectomy and Wernicke Encephalopathy. American journal of therapeutics. 2017 Jul/Aug:24(4):e504-e505. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000000476. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27415978]

Zheng L. Wernicke Encephalopathy and Sleeve Gastrectomy: A Case Report and Literature Review. American journal of therapeutics. 2016 Nov/Dec:23(6):e1958-e1961 [PubMed PMID: 26539904]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMechanick JI, Apovian C, Brethauer S, Timothy Garvey W, Joffe AM, Kim J, Kushner RF, Lindquist R, Pessah-Pollack R, Seger J, Urman RD, Adams S, Cleek JB, Correa R, Figaro MK, Flanders K, Grams J, Hurley DL, Kothari S, Seger MV, Still CD. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Perioperative Nutrition, Metabolic, and Nonsurgical Support of Patients Undergoing Bariatric Procedures - 2019 Update: Cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology, The Obesity Society, American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, Obesity Medicine Association, and American Society of Anesthesiologists. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.). 2020 Apr:28(4):O1-O58. doi: 10.1002/oby.22719. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32202076]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePacei F, Iaccarino L, Bugiardini E, Dadone V, De Toni Franceschini L, Colombo C. Wernicke's encephalopathy, refeeding syndrome and wet beriberi after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: the importance of thiamine evaluation. European journal of clinical nutrition. 2020 Apr:74(4):659-662. doi: 10.1038/s41430-020-0583-x. Epub 2020 Feb 11 [PubMed PMID: 32047291]

Shoar S, Saber AA. Long-term and midterm outcomes of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 2017 Feb:13(2):170-180. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.08.011. Epub 2016 Aug 18 [PubMed PMID: 27720197]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence