Introduction

Shock is a condition when there is a discrepancy between the needs of the tissues and their supply of oxygen and nutrients. It is due to the dysfunction of the circulatory system in providing blood to the tissues to adequately meet the metabolic requirements and the insufficient removal of waste products of metabolism. The most common cause of shock in the pediatric population is hypovolemic shock, whereas, in adults, it is septic shock. Refractory shock is variably defined as persistent hypotension with end-organ dysfunction despite fluid resuscitation, high-dose vasopressors, oxygenation, and ventilation. Fluid resuscitation and vasopressors are the initial approaches to the management of shock. Overuse of fluids in critically ill patients can lead to pulmonary edema, hypoxemic respiratory failure, and organ edema.[1]

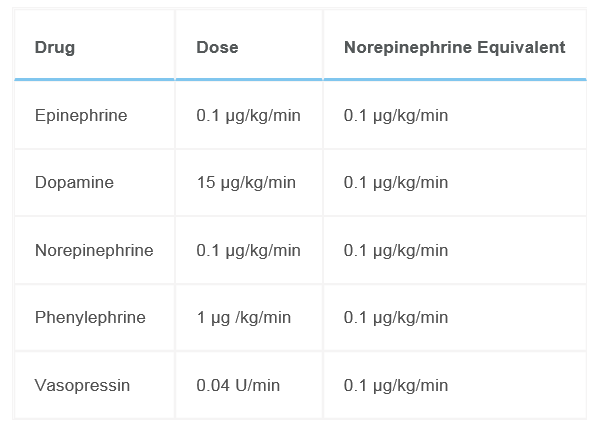

High doses of catecholamines can induce arrhythmias and ischemia.[2] The strongest predictor of mortality in critically ill patients is the vasopressor dose that is required to maintain the mean arterial pressure (MAP) goal. High dose vasopressor doses can be defined by converting other vasopressors to norepinephrine equivalents of > 0.2 micrograms/kg/min.[3] There are no standard guidelines for the management of refractory shock, but a few randomized studies guide clinical management.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

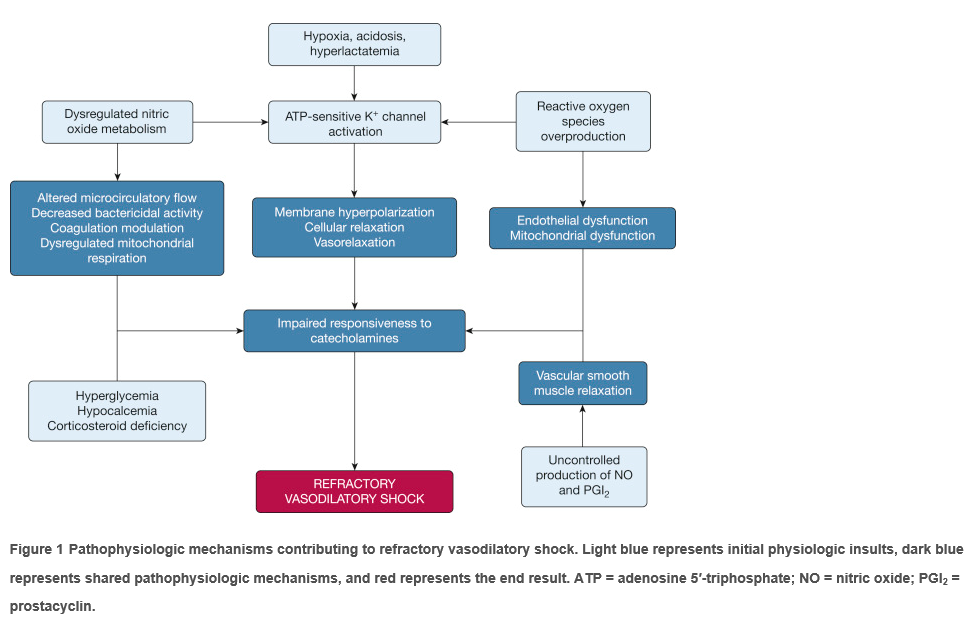

Refractory shock is a vasodilatory shock resulting from the impaired responsiveness of catecholamines. Excess amounts of the vasodilatory nitric oxide (NO) and relative or absolute deficiencies of endogenous vasoactive hormones, such as vasopressin, cortisol, vitamin B1, ascorbic acid, and angiotensin II lead to vasorelaxation. Hypoxia, metabolic acidosis, and elevated lactate levels lead to activation of adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels present in smooth muscle cells, which prevents calcium entry that is required for vasoconstriction.

Epidemiology

Refractory vasodilatory shock is seen whenever there is a cardiovascular failure. It frequently follows septic shock. Mortality in refractory shock exceeds 50%. Almost 6%-7% of critically ill patients in the ICU may develop refractory shock.[4]

History and Physical

Refractory shock manifests as end-organ dysfunction. The physical exam should focus on assessing the extent of organ dysfunction. The central nervous system manifests as altered sensorium, the cardiovascular system manifests as low blood pressure and pump failure, the kidney manifests as oliguria/anuria, the gut manifests as ileus or ischemia, the respiratory system manifests as hyperventilation/acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and skin with a decreased capillary refill.

Delivery of oxygen can be assessed subjectively through dyspnea, capillary refill, mental status (using the Glasgow Coma Scale), and urine output, and objectively through lactate level, mixed venous saturation, heart rate, and blood pressure.

Evaluation

Evaluation should focus on the identification of the primary cause and reversible secondary contributors, such as hypovolemia, pump failure, or obstruction that is causing shock. Patients must be placed on continuous cardiopulmonary monitoring.

The following labs should be monitored: Complete blood count with differential (CBC-d), basic metabolic profile with liver function test, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) panel, arterial blood gas, urinalysis, and pan cultures (blood, urine, wound, tracheal if intubated). Inflammatory markers, including C-reactive protein or procalcitonin and lactate levels, should be monitored. A chest x-ray should be obtained to monitor the degree of ARDS.

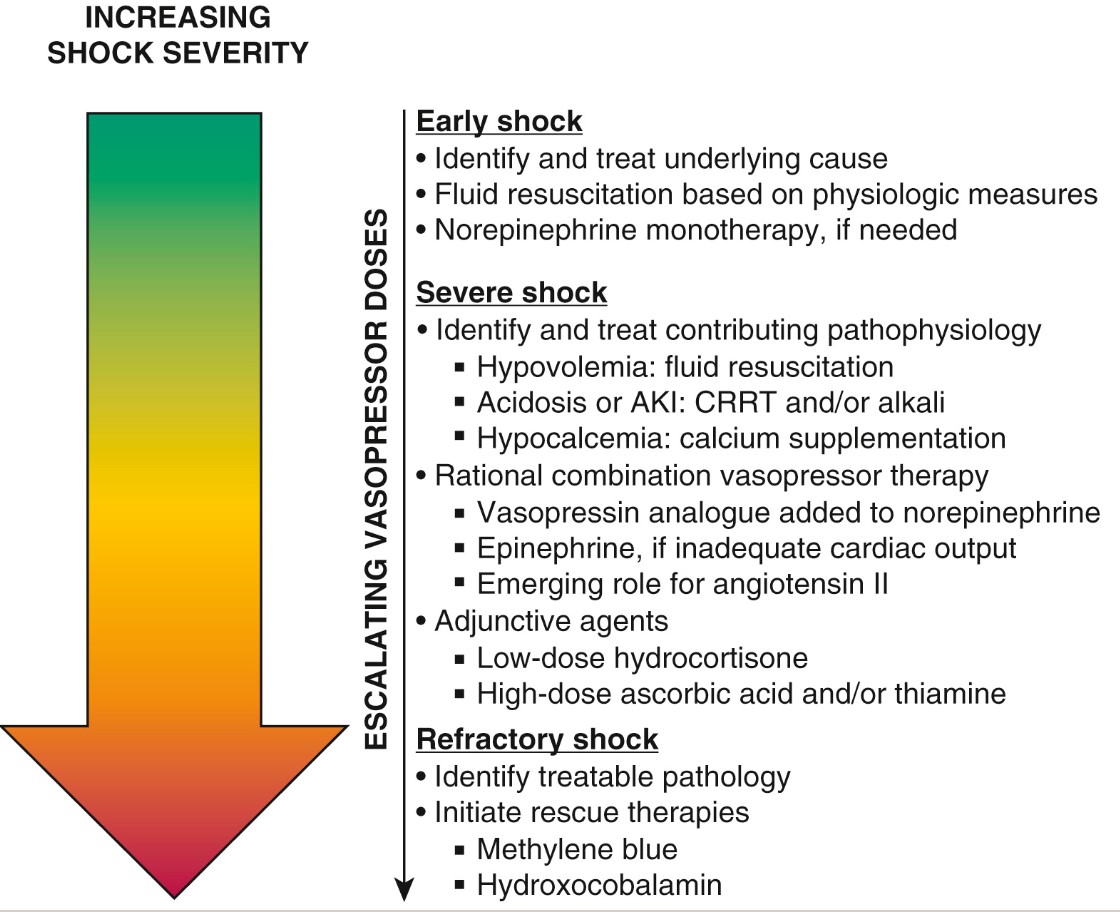

Treatment / Management

The first step in management is to identify and treat the contributing etiology. Early identification and management of compensated shock help in preventing its progression to refractory shock. Fluid resuscitation in hypovolemic shock and vasopressors in fluid refractory shock should be administered. Most adult patients need a minimum MAP goal > 65 mmHg. Norepinephrine is the first-line choice of vasopressor in septic shock. In cases of cold shock with low cardiac output, epinephrine is the first-line choice of drug. Combination vasopressor therapy is expected to yield better outcomes before the onset of refractory shock has been shown with vasopressin.[5](A1)

Vasopressin or antidiuretic hormone, which is stored and released from the posterior pituitary, is relatively deficient in sepsis. Vasopressin acts on V1 and V2 receptors, causing vascular smooth muscle contraction and water reabsorption in collecting tubules of the kidney. Unlike catecholamines, vasopressin does not cause arrhythmias and can work in an acidic environment. It has been shown to decrease catecholamine requirements and is associated with decreased mortality in less severe shock. Vasopressin, when used with a corticosteroid, has shown decreased mortality suggesting possible synergy.[6] (A1)

Minimize sedation: Sedatives are known to exacerbate hypotension through systemic vasodilation and myocardial depression. Surviving sepsis guidelines suggest minimizing sedation in patients with sepsis who are dependent on mechanical ventilation.[7]

Continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT): It allows rapid control of temperature and metabolic acidosis correction in patients with shock. It also contributes to a reduction in vasopressor requirements and improves cardiac output. There are concerns about the removal of antibiotics and vitamins/trace elements, but appropriate compensation of antibiotics and vitamin/trace element supplementation can be done.[8](A1)

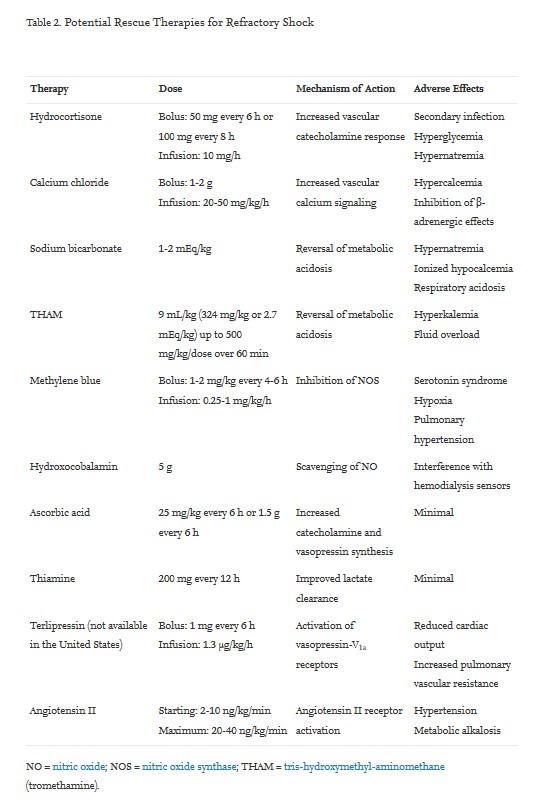

Potential Rescue Therapies for Refractory Shock [9]

Various rescue treatment options for refractory shock have been described to benefit hemodynamic variables, but none of these therapies has shown any definite reduction in mortality or proven superior to others.

Glucocorticoid therapy: Glucocorticoids reduce inflammation-mediated vasodilation. There could be refractory vasodilation secondary to relative adrenal insufficiency in patients with shock. Hydrocortisone can be given 100 mg every 8 hours or 50 mg every 6 hours. A synergistic effect has been reported when combined with vasopressin. Hydrocortisone infusion has shown improved shock reversal, but its effect on the duration of shock, length of intensive care unit (ICU) stay, and mortality remains controversial.[10] (A1)

Correction of acidemia: Vasopressor responsiveness decreases in acidic environments markedly when arterial pH is < 7.15 because of impaired catecholamine signaling. Sodium bicarbonate can be used to reverse metabolic acidosis, but it can cause harmful effects like respiratory acidosis, paradoxic intracellular acidosis, hypocalcemia, myocardial depression, hypernatremia, and elevated lactate levels. THAM/tromethamine is a non-bicarbonate buffer used as an alternative to sodium bicarbonate.

Calcium supplementation: Hypocalcemia is commonly seen in severe sepsis patients, possibly secondary to calcium chelation by citrate in transfused blood products or acquired parathyroid insufficiency, vitamin D deficiency, renal 1a-hydroxylase insufficiency, and acquired calcitriol resistance. Intracellular calcium signaling is an important mechanism that leads to the contraction of cardiac and vascular smooth muscle. Severe hypocalcemia can cause hypotension due to depressed cardiovascular function. Calcium chloride administration as a bolus increases vascular tone, thus increasing MAP without increasing cardiac output. Potential adverse effects are hypercalcemia and blunting of beta-adrenergic effects.

Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) is an important cofactor that is required for the synthesis of endogenous norepinephrine and vasopressin. Vitamin C cannot be synthesized by the body and should be given as a supplement. Critically ill patients have a relative or absolute deficiency of vitamin C, which may contribute to refractory shock due to deficiency of endogenous catecholamines. Vitamin C has powerful antioxidant properties and improves macrophage and T-cell immunity. High-dose, intravenous vitamin C (25 mg/kg or 1.5 g every 6 hours) may reduce inflammation, enhance hemodynamic variables, and organ function.

Vitamin B1 (thiamine) is an essential cofactor in oxidative energy metabolism and lactate metabolism. Relative or absolute thiamine deficiency is observed in patients with septic shock that can contribute to cardiovascular compromise and lactic acidosis. IV thiamine replacement may also be associated with improved lactate clearance and renal function and a reduced need for CRRT. Thiamine, when combined with hydrocortisone and high-dose vitamin C, has shown improved shock reversal and decreased severity of organ failure.

NO inhibitors: An overproduction by iNOS leads to vasodilation. NO can cause harmful effects on mitochondrial and organ function.

Methylene blue can reverse vasodilation caused by excessive NO signaling in septic shock and can be used in post-operative cardiac care. It may inhibit monoamine oxidase, and cause serotonin syndrome, and can increase pulmonary vascular resistance in some patients. It should be used with caution in patients who are receiving continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration, as the drug may not be eliminated by hemodiafiltration.[11](B3)

Hydroxocobalamin, a vitamin B12 precursor, can reverse NO-mediated vasodilation by acting as an NO scavenger. Hydroxocobalamin should be used with caution in patients on hemodialysis with acute kidney injury as it remains in the bloodstream and urine for days to weeks.

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) provides good cardiopulmonary support temporarily in postcardiotomy shock patients. It improves global oxygen delivery and helps in treating refractory hypoxemia from pulmonary failure. It improves by clearing carbon dioxide and acid-base management. It improves myocardial function and is used in refractory cardiogenic shock.

Intra-aortic balloon pumps and percutaneous left ventricular assist devices (LVAD) are used for refractory cardiogenic heart.

Extracorporeal cytokine elimination by extracorporeal cytokine adsorbers used in refractory septic shock reduced the use of noradrenaline dose and improved lactate clearance and shock reversal.[12]

Therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) is a novel method that can remove pathologically increased cytokines in refractory septic shock but can also simultaneously replace protective factors in plasma.[13]

Polymyxin B hemoperfusion has been shown to improve hemodynamics, organ function, and mortality.[14] (B2)

Future Therapies

Terlipressin: It is a long-acting vasopressin analog that acts on the V1a receptor with partial selectivity. Like vasopressin, it increases MAP and reduces vasopressor requirements in vasodilatory shock. However, when administered as a bolus, it can cause a decrease in cardiac output needing inotropes.

Selepressin: It is a synthetic selective vasopressin-V1a receptor agonist. Like vasopressin, it increases MAP and decreases the catecholamine requirements but is not associated with fluid overload from retaining water and thrombosis from the release of von Willebrand factor.

Synthetic human angiotensin II: Angiotensin II is the key component of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. Functional angiotensin II or angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) deficiency may appear in sepsis leading to refractory shock. Angiotensin II increases MAP, decreases the need for other vasopressors, and has shown favorable outcomes in patients with less severe shock.[15][16](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

- Septic shock

- Vasodilatory shock

- Cardiogenic shock

Prognosis

Refractory shock carries a poor prognosis with mortality of up to 60%. The strongest predictor of mortality in critically ill patients is the vasopressor dose that is required to maintain the mean arterial pressure (MAP) goal. Decreased mortality has been reported with the use of vasopressin and angiotensin II in patients with less severe shock (with baseline norepinephrine requirements <15 mg/min).

Complications

- End organ dysfunction

- Multi-organ failure

- Death

Deterrence and Patient Education

Early initiation of combination vasopressor therapy has shown a mortality benefit. Reversal of shock can be achieved with hydrocortisone and vasopressin. The use of vasopressin and angiotensin II has shown a decrease in mortality in patients with less severe shock.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Refractory shock carries a mortality rate of up to 60%. The key to survival is to identify the cause and treat promptly and initiate combination vasopressor therapy early. Unfortunately, even with multiple rescue therapies, multi-organ failure is common, so patient monitoring is vital. An interprofessional team of intensivists, ICU nurses, and pharmacists should work together in identifying any drug interactions and choice of rescue therapy. The ICU nurses should monitor the patient for signs of organ failure like oliguria, poor oxygenation, coagulopathy, loss of pulses, abdominal pain (secondary to mesenteric ischemia), and stroke. Close communication is important between the interprofessional team to improve outcomes. If the patient undergoes cardiac surgery, monitoring complications is vital.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Pathophysiologic mechanisms contributing to refractory vasodilatory shock. Light blue represents initial physiologic insults, dark blue represents shared pathophysiologic mechanisms, and red represents the end result. ATP = adenosine 5′-triphosphate; NO = nitric oxide; PGI2 = prostacyclin. Contributed by Jacob C. Jentzer, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

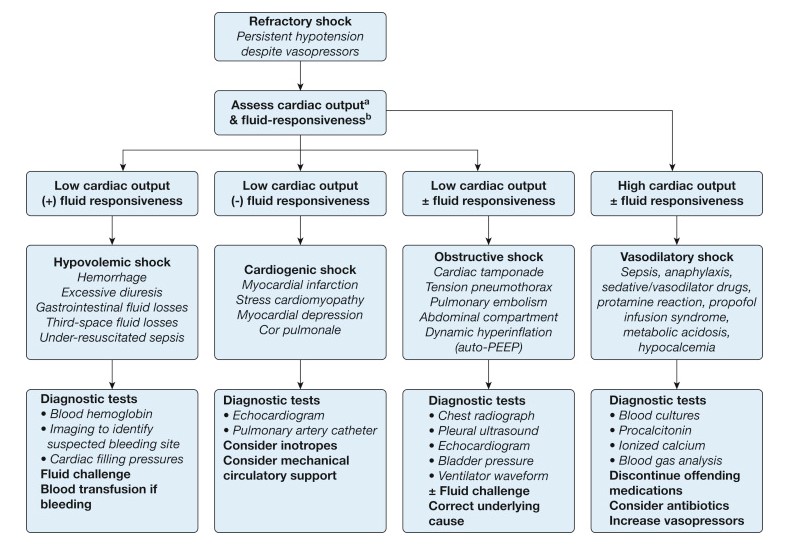

Suggested diagnostic approach for identifying reversible contributors to refractory shock, based on assessment of cardiac output and fluid responsiveness. a Measurement of central or mixed venous oxygen saturation can be used as a surrogate for cardiac output in many patients. b Measures of fluid responsiveness can include respiratory pulse-pressure or stroke volume variation and passive straight-leg raise. PEEP = positive end-expiratory pressure. Contributed by Jacob C. Jentzer, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Malbrain ML, Marik PE, Witters I, Cordemans C, Kirkpatrick AW, Roberts DJ, Van Regenmortel N. Fluid overload, de-resuscitation, and outcomes in critically ill or injured patients: a systematic review with suggestions for clinical practice. Anaesthesiology intensive therapy. 2014 Nov-Dec:46(5):361-80. doi: 10.5603/AIT.2014.0060. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25432556]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSchmittinger CA, Torgersen C, Luckner G, Schröder DC, Lorenz I, Dünser MW. Adverse cardiac events during catecholamine vasopressor therapy: a prospective observational study. Intensive care medicine. 2012 Jun:38(6):950-8. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2531-2. Epub 2012 Apr 12 [PubMed PMID: 22527060]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDe Backer D, Biston P, Devriendt J, Madl C, Chochrad D, Aldecoa C, Brasseur A, Defrance P, Gottignies P, Vincent JL, SOAP II Investigators. Comparison of dopamine and norepinephrine in the treatment of shock. The New England journal of medicine. 2010 Mar 4:362(9):779-89. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907118. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20200382]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJenkins CR,Gomersall CD,Leung P,Joynt GM, Outcome of patients receiving high dose vasopressor therapy: a retrospective cohort study. Anaesthesia and intensive care. 2009 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 19400494]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRussell JA, Walley KR, Singer J, Gordon AC, Hébert PC, Cooper DJ, Holmes CL, Mehta S, Granton JT, Storms MM, Cook DJ, Presneill JJ, Ayers D, VASST Investigators. Vasopressin versus norepinephrine infusion in patients with septic shock. The New England journal of medicine. 2008 Feb 28:358(9):877-87. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067373. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18305265]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRussell JA, Walley KR, Gordon AC, Cooper DJ, Hébert PC, Singer J, Holmes CL, Mehta S, Granton JT, Storms MM, Cook DJ, Presneill JJ, Dieter Ayers for the Vasopressin and Septic Shock Trial Investigators. Interaction of vasopressin infusion, corticosteroid treatment, and mortality of septic shock. Critical care medicine. 2009 Mar:37(3):811-8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181961ace. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19237882]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer R, Kumar A, Sevransky JE, Sprung CL, Nunnally ME, Rochwerg B, Rubenfeld GD, Angus DC, Annane D, Beale RJ, Bellinghan GJ, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith C, De Backer DP, French CJ, Fujishima S, Gerlach H, Hidalgo JL, Hollenberg SM, Jones AE, Karnad DR, Kleinpell RM, Koh Y, Lisboa TC, Machado FR, Marini JJ, Marshall JC, Mazuski JE, McIntyre LA, McLean AS, Mehta S, Moreno RP, Myburgh J, Navalesi P, Nishida O, Osborn TM, Perner A, Plunkett CM, Ranieri M, Schorr CA, Seckel MA, Seymour CW, Shieh L, Shukri KA, Simpson SQ, Singer M, Thompson BT, Townsend SR, Van der Poll T, Vincent JL, Wiersinga WJ, Zimmerman JL, Dellinger RP. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Critical care medicine. 2017 Mar:45(3):486-552. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002255. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28098591]

Borthwick EM, Hill CJ, Rabindranath KS, Maxwell AP, McAuley DF, Blackwood B. High-volume haemofiltration for sepsis in adults. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017 Jan 31:1(1):CD008075. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008075.pub3. Epub 2017 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 28141912]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJentzer JC, Vallabhajosyula S, Khanna AK, Chawla LS, Busse LW, Kashani KB. Management of Refractory Vasodilatory Shock. Chest. 2018 Aug:154(2):416-426. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.12.021. Epub 2018 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 29329694]

Annane D, Sébille V, Charpentier C, Bollaert PE, François B, Korach JM, Capellier G, Cohen Y, Azoulay E, Troché G, Chaumet-Riffaud P, Bellissant E. Effect of treatment with low doses of hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone on mortality in patients with septic shock. JAMA. 2002 Aug 21:288(7):862-71 [PubMed PMID: 12186604]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMount JC, Rowe AS. Use of methylene blue for refractory septic shock during continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration. Pharmacotherapy. 2010 Mar:30(3):323. doi: 10.1592/phco.30.3.323. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20180614]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFriesecke S, Stecher SS, Gross S, Felix SB, Nierhaus A. Extracorporeal cytokine elimination as rescue therapy in refractory septic shock: a prospective single-center study. Journal of artificial organs : the official journal of the Japanese Society for Artificial Organs. 2017 Sep:20(3):252-259. doi: 10.1007/s10047-017-0967-4. Epub 2017 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 28589286]

David S, Hoeper MM, Kielstein JT. [Plasma exchange in treatment refractory septic shock : Presentation of a therapeutic add-on strategy]. Medizinische Klinik, Intensivmedizin und Notfallmedizin. 2017 Feb:112(1):42-46. doi: 10.1007/s00063-015-0117-9. Epub 2015 Nov 24 [PubMed PMID: 26604091]

Monti G, Terzi V, Calini A, Di Marco F, Cruz D, Pulici M, Brioschi P, Vesconi S, Fumagalli R, Casella G. Rescue therapy with polymyxin B hemoperfusion in high-dose vasopressor therapy refractory septic shock. Minerva anestesiologica. 2015 May:81(5):516-25 [PubMed PMID: 25319136]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAntonucci E, Gleeson PJ, Annoni F, Agosta S, Orlando S, Taccone FS, Velissaris D, Scolletta S. Angiotensin II in Refractory Septic Shock. Shock (Augusta, Ga.). 2017 May:47(5):560-566. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000807. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27879559]

Chawla LS, Russell JA, Bagshaw SM, Shaw AD, Goldstein SL, Fink MP, Tidmarsh GF. Angiotensin II for the Treatment of High-Output Shock 3 (ATHOS-3): protocol for a phase III, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Critical care and resuscitation : journal of the Australasian Academy of Critical Care Medicine. 2017 Mar:19(1):43-49 [PubMed PMID: 28215131]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence