Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Brachialis Muscle

Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Brachialis Muscle

Introduction

The brachialis is an important flexor muscle of the forearm at the elbow.[1] The brachialis provides elbow flexion at all physiologic positions and is considered a "pure flexor" of the forearm at the elbow.[2] It lies in the anteroinferior area of the arm and is deeper than the biceps brachialis muscle. Brachialis contributes to the upper part of the anatomically important antecubital fossa of the elbow joint.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

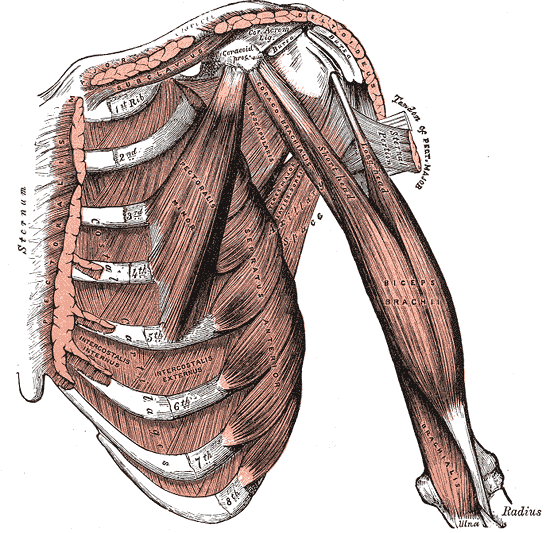

The brachialis is an elbow flexor that originates from the distal anterior humerus and inserts onto the ulnar tuberosity. The brachialis is 1 of the largest elbow flexors and provides pure forearm flexion at the elbow.[2] It does not provide any supination or pronation of the forearm. See Image. Internal Muscles of the Chest and Shoulder. Within the literature, there are conflicting reports of the detailed anatomy of the brachialis. Traditionally, the brachialis has been described as a single-head muscle, although cadaver assessment has demonstrated that the brachialis muscle may have 2 heads, 1 superficial and 1 deep.[3] The superficial head forms the major head, which originates from the anterior mid-shaft humerus and the lateral intermuscular septum and inserts onto the ulnar tuberosity.[3] In detail, the insertion of the deep head has 3 portions: medial and lateral aponeurosis and muscular contractile fibers that attach directly to the ulna.[3] The deep head forms a smaller muscle that originates from the anterior humerus and the medial intermuscular septum and inserts mainly into an aponeurosis that branches to the ulna. Furthermore, different anatomic variants have been described in the literature, with the potential for real clinical implications. The brachialis muscle is the strongest flexor of the elbow in the absence of supination, as with supination and flexion, its mechanical momentum becomes more disadvantaged than the biceps brachialis muscle.

Embryology

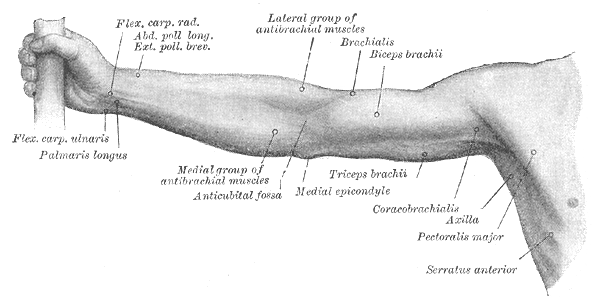

As a skeletal muscle, the brachialis ultimately develops from the mesoderm layer.[4] The upper extremity musculature develops from a common muscle of origin, muscle primordia, that later develops into specific muscle heads (see Image. Right Upper Extremity Surface Anatomy).[5][6] Specifically, the muscle primordia develops from dorsolateral somite cells that migrate into limb buds around day 28 of development.[5] The muscle primordia later split into separate flexor and extensor components. This division is controlled by signaling from connective tissue deriving from the lateral plate mesoderm.[5][6] Notably, anterior-posterior development is under the control of downstream signaling of sonic hedgehog protein, secreted at the zone of polarizing activity in the posterior limb bud.[5][6] Dorsoventral differentiation is under the control of WNT7A and downstream signaling pathways thereof.[5][6] Differences in these complex developmental pathways can ultimately lead to different anatomic variants. These variants can also significantly influence surrounding neural and vascular structures.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The blood supply of the brachialis ultimately comes from the tributaries of the brachial artery and the radial recurrent artery. Occasionally, other arteries may supply the brachialis, including branches of the ulnar collateral arteries. The venous drainage from the brachialis muscle is ultimately the brachial vein, which later joins with the basilic vein tributary and forms the axillary vein. The upper limb contains both superficial and deep lymphatic channels. The superficial channels generally follow superficial vasculature and perforate into the deep lymphatics at various points, particularly near the cubital fossa. The deep lymphatic channels generally follow the main vessels and ultimately drain into the axillary lymph nodes.[7] It bears mentioning that research has documented various anatomic variants of this relevant vasculature.[8][9][10]

Nerves

The brachialis often has dual innervation, innervated medially by the musculocutaneous nerve and laterally by the radial nerve.[11][12] However, the musculocutaneous nerve provides most of the motor supply to the muscle. Other anatomic variants have also been described, including individual innervation by the musculocutaneous and median nerve.[13] The musculocutaneous nerve passes between the biceps and brachialis muscles, wherein the terminal branch of the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve emerges. The radial nerve passes between the brachialis and brachioradialis muscles in the lateral arm after spiraling and emerging from the spiral groove of the humerus.[14] However, there is documentation of anatomic variants of the brachialis muscle, which have influenced nerve location and innervation patterns.[15]

Muscles

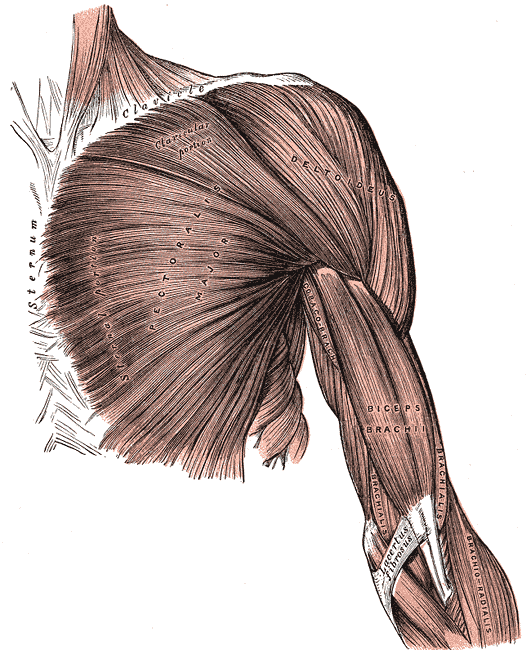

The brachialis muscle relates anteriorly to the biceps muscle, the brachioradialis muscle, the pronator teres muscle, and the vascular-nerve bundle of the arm. See Image. Superficial Muscles of the Chest and Shoulder.

Physiologic Variants

There have been some reports of anatomic variants of the brachialis muscle.[16] One case report discussed an accessory brachialis muscle found during cadaver dissection at Harvard Medical School in 2003.[17] The accessory brachialis muscle originated from the mid-shaft of the humerus and the medial intermuscular septum. It crossed both the median nerve and brachial artery before inserting into the common tendon of the elbow flexor muscles.[17] Another report described an accessory brachialis muscle that included a fibrous/muscular tunnel containing the brachial artery and median nerve, suggesting that this anatomic variant could yield nerve compression symptomatology with muscle contraction.[18]

Surgical Considerations

The brachialis typically gets split during anterior and anterolateral surgical approaches to the humerus.[11] Such methods are common for humerus fractures, particularly supracondylar humerus fractures.[19] Of note, a supracondylar fracture of the humerus is 1 of the most common pediatric injuries of the elbow region. Estimates show that it accounts for between 15 and 17% of childhood extremity fractures.[20] Given the importance of the brachialis muscle and the proximity to various neurovascular elements, this approach requires extreme care. Notably, cadaver studies have demonstrated that anterolateral splitting of the brachialis yields a significant probability of damaging lateral branch nerve supply, even when the brachialis receives dual innervation (eg, from both the musculocutaneous and radial nerves).[11] Given anatomic variability, it may be difficult to predict the exact location of essential nerves within these muscle compartments, further complicating the surgical approach.[11] Some have described utilizing a lateral approach that does not split the brachialis muscle. However, there is a concern that the required manipulation and dissection may increase the risk of post-operative nerve palsy.[21]

Clinical Significance

The brachialis muscle is an important elbow flexor, so it is clinically relevant. Impaired elbow flexion can result from several etiologies, including neurologic, neurovascular, muscle rupture, or traumatic causes. Generally, injury to the biceps brachii is more commonly the cause of elbow flexor trauma, although there is also documentation of isolated injuries to the brachialis muscle.[22][23][24][25] The majority of these cases were attributable to either overuse injuries or strenuous weight-loading injuries. Magnetic resonance imaging is generally the most accurate means of diagnosing these isolated muscle ruptures. However, there are also suggestions regarding using ultrasound for diagnosis as a low-risk and cost-effective alternative.[24] Although the literature is limited, some have suggested that conservative, non-surgical management is sufficient for uncomplicated, isolated brachialis injury.[24]

Additionally, there has been documented use of brachialis tendon transfer, specifically to reconstruct the flexor digitorum profundus and the flexor pollicis longus after brachial plexus injuries.[26] The brachialis is an alternative donor for such applications since forearm muscles are not always available for use in these procedures. This study demonstrated that this donor strategy achieved "key pinch" and "hook grasp" in these patients.[26] For a manual evaluation of the strength of the brachialis muscle, the operator puts his resistance on the patient's wrist. At the same time, the latter holds the elbow extended and with the palm forward. The patient has to flex the elbow without supination; in this way, we are evaluating the flexor muscle strongest at the elbow.

Other Issues

Brachialis syndrome results from a permanent injury to the median nerve following poor patient positioning during surgery, particularly due to a decompression of the median nerve in the antecubital fossa.[27] According to the literature, the brachialis muscle could be 1 of the causes of the alteration of the arthrokinematics of the shoulder (thanks to the anatomic-myofascial continuum), causing pain to the movement and disturbance to the rotator cuff of the shoulder. The presence of trigger points in the brachialis muscle could be a clue. In some patients, injecting drugs in the brachialis muscle can solve the shoulder problem. Myositis ossificans in the sporting field generally involve specific muscle areas, including the brachialis muscle (see Image. Myositis Ossificans of the Brachialis Muscle).[28] The approach is often conservative, and the athlete has excellent chances of returning to full function. In severe cases where surgery is indicated, ensuring the process fully develops before intervening is essential.[29] Furthermore, radiotherapy may have a role in improving post-operative pain and functional outcomes.[30] Angiosarcoma formation can affect the brachialis muscle, particularly in deep tissues.[31] Angiosarcoma may present as a deep swelling or hematoma; a bioptic test is required to understand the nature of the swelling. Tendinopathy of the brachialis muscle at its insertion is a rare event. Generally, the symptom is pain in the antecubital area, and conservative therapy (steroid injection) is the recommended approach to management.[32]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Superficial Muscles of the Chest and Shoulder. This illustration shows the pectoralis major, deltoid, coracobrachialis biceps brachii, brachialis, and brachioradialis. Other structures included in this image are the clavicle, sternum, and lacertus fibrosus.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Internal Muscles of the Chest and Shoulder. The internal muscles of the chest and shoulder include the pectoralis, deltoid, subclavius, costal cartilages, ribs, pectoralis minor, serratus anterior, biceps brachii, coracobrachialis, and brachialis.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Right Upper Extremity Surface Anatomy. This anterior view shows the surface markings of the flexor carpi radialis, abductor and exterior pollicis longus and brevis, palmaris longus, medial antebrachial muscles, antecubital fossa, lateral antebrachial muscles, brachialis, biceps brachii, triceps brachii, and medial epicondyle.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Ilayperuma I, Uluwitiya SM, Nanayakkara BG, Palahepitiya KN. Re-visiting the brachialis muscle: morphology, morphometry, gender diversity, and innervation. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2019 Apr:41(4):393-400. doi: 10.1007/s00276-019-02182-2. Epub 2019 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 30820647]

Palazzi S, Palazzi JL, Caceres JP. Neurotization with the brachialis muscle motor nerve. Microsurgery. 2006:26(4):330-3 [PubMed PMID: 16685741]

Leonello DT, Galley IJ, Bain GI, Carter CD. Brachialis muscle anatomy. A study in cadavers. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2007 Jun:89(6):1293-7 [PubMed PMID: 17545433]

Endo T, Molecular mechanisms of skeletal muscle development, regeneration, and osteogenic conversion. Bone. 2015 Nov; [PubMed PMID: 26453493]

Guéro S. Developmental biology of the upper limb. Hand surgery & rehabilitation. 2018 Oct:37(5):265-274. doi: 10.1016/j.hansur.2018.03.007. Epub 2018 Jul 21 [PubMed PMID: 30041930]

Zeller R, López-Ríos J, Zuniga A. Vertebrate limb bud development: moving towards integrative analysis of organogenesis. Nature reviews. Genetics. 2009 Dec:10(12):845-58. doi: 10.1038/nrg2681. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19920852]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMa CX, Pan WR, Liu ZA, Zeng FQ, Qiu ZQ, Liu MY. Deep lymphatic anatomy of the upper limb: An anatomical study and clinical implications. Annals of anatomy = Anatomischer Anzeiger : official organ of the Anatomische Gesellschaft. 2019 May:223():32-42. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2019.01.005. Epub 2019 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 30716466]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKusztal M,Weyde W,Letachowicz K,Gołebiowski T,Letachowicz W, Anatomical vascular variations and practical implications for access creation on the upper limb. The journal of vascular access. 2014; [PubMed PMID: 24817459]

Rodríguez-Niedenführ M, Vázquez T, Nearn L, Ferreira B, Parkin I, Sañudo JR. Variations of the arterial pattern in the upper limb revisited: a morphological and statistical study, with a review of the literature. Journal of anatomy. 2001 Nov:199(Pt 5):547-66 [PubMed PMID: 11760886]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHaładaj R, Wysiadecki G, Dudkiewicz Z, Polguj M, Topol M. The High Origin of the Radial Artery (Brachioradial Artery): Its Anatomical Variations, Clinical Significance, and Contribution to the Blood Supply of the Hand. BioMed research international. 2018:2018():1520929. doi: 10.1155/2018/1520929. Epub 2018 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 29992133]

Frazer EA, Hobson M, McDonald SW. The distribution of the radial and musculocutaneous nerves in the brachialis muscle. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2007 Oct:20(7):785-9 [PubMed PMID: 17854055]

Pacha Vicente D, Forcada Calvet P, Carrera Burgaya A, Llusá Pérez M. Innervation of biceps brachii and brachialis: Anatomical and surgical approach. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2005 Apr:18(3):186-94 [PubMed PMID: 15768419]

Won SY, Cho YH, Choi YJ, Favero V, Woo HS, Chang KY, Hu KS, Kim HJ. Intramuscular innervation patterns of the brachialis muscle. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2015 Jan:28(1):123-7. doi: 10.1002/ca.22387. Epub 2014 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 24596238]

Bhardwaj P, Venkatramani H, Sivakumar B, Graham DJ, Vigneswaran V, Sabapathy SR. Anatomic Variations of the Musculocutaneous Nerve and Clinical Implications for Restoration of Elbow Flexion. The Journal of hand surgery. 2022 Oct:47(10):970-978. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2022.07.014. Epub 2022 Sep 3 [PubMed PMID: 36064510]

Thieffry C, Chenin L, Foulon P, Havet E, Peltier J. Microsurgical anatomy of branches of musculocutaneous nerve: clinical relevance for spastic elbow surgery. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2017 Jul:39(7):773-778. doi: 10.1007/s00276-016-1800-0. Epub 2016 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 28039506]

Pai MM, Nayak SR, Vadgaonkar R, Ranade AV, Prabhu LV, Thomas M, Sugavasi R. Accessory brachialis muscle: a case report. Morphologie : bulletin de l'Association des anatomistes. 2008 Mar:92(296):47-9. doi: 10.1016/j.morpho.2008.04.003. Epub 2008 May 19 [PubMed PMID: 18487066]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLoukas M, Louis RG Jr, South G, Alsheik E, Christopherson C. A case of an accessory brachialis muscle. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2006 Sep:19(6):550-3 [PubMed PMID: 16917824]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVadgaonkar R, Rai R, Ranade AV, Nayak SR, Pai MM, Lakshmi R. A case report on accessory brachialis muscle. Romanian journal of morphology and embryology = Revue roumaine de morphologie et embryologie. 2008:49(4):581-3 [PubMed PMID: 19050812]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKoudstaal MJ, De Ridder VA, De Lange S, Ulrich C. Pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures: the anterior approach. Journal of orthopaedic trauma. 2002 Jul:16(6):409-12 [PubMed PMID: 12142829]

Cheng JC, Shen WY. Limb fracture pattern in different pediatric age groups: a study of 3,350 children. Journal of orthopaedic trauma. 1993:7(1):15-22 [PubMed PMID: 8433194]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMills WJ, Hanel DP, Smith DG. Lateral approach to the humeral shaft: an alternative approach for fracture treatment. Journal of orthopaedic trauma. 1996:10(2):81-6 [PubMed PMID: 8932665]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCurry EJ, Cusano A, Elattar O, Bogart A, Murakami A, Li X. Brachialis Muscle Tendon Rupture of the Distal Ulnar Attachment in a Competitive Weight Lifter. Orthopedics. 2019 May 1:42(3):e339-e342. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20190221-04. Epub 2019 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 30810756]

Costa JH,Marques TP, Traumatic rupture of the brachialis muscle in a 52-year-old man. BMJ case reports. 2015 Jul 10; [PubMed PMID: 26163553]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchönberger TJ, Ernst MF. A brachialis muscle rupture diagnosed by ultrasound; case report. International journal of emergency medicine. 2011 Jul 26:4(1):46. doi: 10.1186/1865-1380-4-46. Epub 2011 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 21791098]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVan den Berghe GR, Queenan JF, Murphy DA. Isolated rupture of the brachialis : a case report. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2001 Jul:83(7):1074-5 [PubMed PMID: 11451979]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBertelli JA, Ghizoni MF. Brachialis muscle transfer to reconstruct finger flexion or wrist extension in brachial plexus palsy. The Journal of hand surgery. 2006 Feb:31(2):190-6 [PubMed PMID: 16473677]

Koehler SM, Meier KM, Lovy A, Fitzpatrick D, Kim J, Hausman MR. Brachialis syndrome: a rare consequence of patient positioning causing postoperative median neuropathy. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 2016 May:25(5):797-801. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.12.023. Epub 2016 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 26948003]

Saad A, Azzopardi C, Patel A, Davies AM, Botchu R. Myositis ossificans revisited - The largest reported case series. Journal of clinical orthopaedics and trauma. 2021 Jun:17():123-127. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2021.03.005. Epub 2021 Mar 13 [PubMed PMID: 33816108]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOrava S, Sinikumpu JJ, Sarimo J, Lempainen L, Mann G, Hetsroni I. Surgical excision of symptomatic mature posttraumatic myositis ossificans: characteristics and outcomes in 32 athletes. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA. 2017 Dec:25(12):3961-3968. doi: 10.1007/s00167-017-4667-7. Epub 2017 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 28780628]

Pakos EE, Pitouli EJ, Tsekeris PG, Papathanasopoulou V, Stafilas K, Xenakis TH. Prevention of heterotopic ossification in high-risk patients with total hip arthroplasty: the experience of a combined therapeutic protocol. International orthopaedics. 2006 Apr:30(2):79-83 [PubMed PMID: 16482442]

Golub IJ, Garcia RA, Wittig JC. A 15-Year-Old Male Baseball Player With a Mass in the Brachialis Muscle. Orthopedics. 2016 May 1:39(3):e545-8. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20160324-03. Epub 2016 Apr 5 [PubMed PMID: 27045482]

McLoughlin E, Iqbal A, Shamji R, James SL, Botchu R. Brachialis tendinopathy: a rare cause of antecubital pain and ultrasound-guided injection technique. Journal of ultrasound. 2021 Sep:24(3):355-358. doi: 10.1007/s40477-019-00378-1. Epub 2019 Apr 20 [PubMed PMID: 31006087]