Introduction

The peritoneum is the serous membrane that lines the abdominal cavity. It is composed of mesothelial cells that are supported by a thin layer of fibrous tissue and is embryologically derived from the mesoderm. The peritoneum serves to support the organs of the abdomen and acts as a conduit for the passage of nerves, blood vessels, and lymphatics. Although the peritoneum is thin, it is made of 2 layers with a potential space between them. The potential space between the 2 layers contains about 50 to 100 ml of serous fluid that prevents friction and allows the layers and organs to glide freely.[1] The outer layer is the parietal peritoneum, which attaches to the abdominal and pelvic walls. The inner visceral layer wraps around the internal organs located inside the intraperitoneal space. The structures bound by the peritoneal cavity may be intraperitoneal or retroperitoneal.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

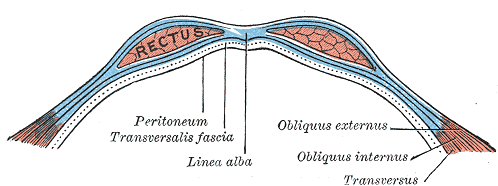

The boundaries of the peritoneal cavity include:

- Anterior abdominal muscles

- Vertebrae

- Pelvic floor

- Diaphragm

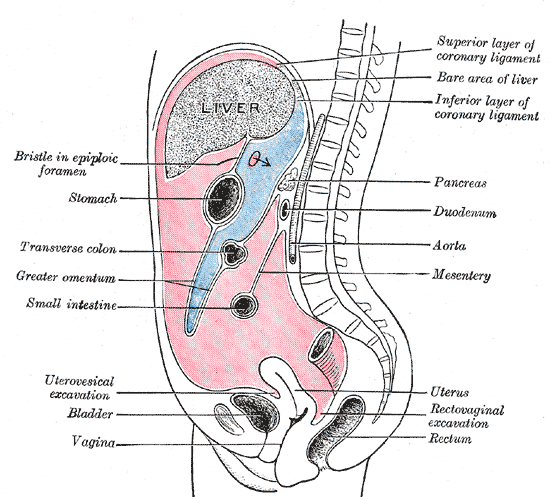

The peritoneum is comprised of 2 layers: the superficial parietal layer and the deep visceral layer. The peritoneal cavity contains the omentum, ligaments, and mesentery. Intraperitoneal organs include the stomach, spleen, liver, first and fourth parts of the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, transverse, and sigmoid colon. Retroperitoneal organs lie behind the posterior sheath of the peritoneum and include the aorta, esophagus, second and third parts of the duodenum, ascending and descending colon, pancreas, kidneys, ureters, and adrenal glands.

An important space in the peritoneal cavity is the epiploic foramen, also known as the foramen of Winslow. This foramen allows communication between the greater and lesser sacs. It is bordered by the hepatoduodenal ligament anteriorly, the inferior vena cava (IVC) posteriorly, duodenum inferiorly, and the caudate lobe of the liver superiorly. The foramen provides access to a surgeon, should they need to clamp the hepatoduodenal ligament to stop a hemorrhage or gain anatomical access to the lesser sac. The foramen can also serve as a location for a lesser sac hernia.

The greater omentum loosely hangs from the greater curvature of the stomach and folds over the anterior of the intestine before curving back superiority to attach to the transverse colon. It acts as a protective or insulating layer. The mesentery helps attach the abdominal organs to the abdominal wall and contains many blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatics. Intraperitoneal organs are usually mobile while those in the retroperitoneum are usually fixed to the posterior abdominal wall. The dorsal mesentery also gives off the transverse and sigmoid mesocolons, which are important due to them containing the blood, nerve, and lymphatic supply for related structures.

Embryology

The peritoneum is derived from mesoderm and helps suspend the primitive gut tube during development. Specifically, the parietal peritoneum is derived from the somatic mesoderm, and visceral peritoneum is derived from the splanchnic mesoderm. It helps suspend the gut tube via ventral and dorsal mesenteries. The mesenteries are extensions of the peritoneum that anchor the anterior and posterior abdominal walls. The ventral mesentery eventually develops into the lesser omentum, which can be further described as the gastrohepatic and hepatoduodenal ligaments, which contains the portal triad and plays a clinical role in potential hemorrhage control in trauma situations. The dorsal mesentery remains as a mesentery, and gives off the gastrosplenic ligament, greater omentum, and helps keep midgut and foregut organs anchored to the posterior abdominal wall.[2]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The parietal peritoneum receives blood from the abdominal wall vasculature, including the iliac, lumbar, epigastric, and intercostal arteries. The visceral peritoneum receives supply from the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries. The two portions of the peritoneum also differ in their venous drainage: the parietal peritoneum drains into the inferior vena cava while the visceral peritoneum drains into the portal vein.[3]

Nerves

A thorough understanding of the innervation of the peritoneum is important as it has clinical implications. The peritoneum has both somatic and autonomic innervations that help explain why various abdominal pathologies, such as peritonitis or appendicitis present the way they do. The parietal peritoneum receives its innervation from spinal nerves T10 through L1. This innervation is somatic and allows for the sensation of pain and temperature that can be localized. The visceral peritoneum receives autonomic innervation from the Vagus nerve and sympathetic innervation that result in the difficult to localize abdominal sensations triggered by organ distension.[2][4]

Surgical Considerations

Inguinal Hernia Repair

The peritoneum plays a significant role in surgical planning for inguinal hernia repairs. The peritoneum is significant enough that the laparoscopic approaches refer to the relationship to the peritoneum with options of a transabdominal pre-peritoneal (TAPP) or total extra pre-peritoneal (TEPP) repairs. In a TAPP, the peritoneum is penetrated, and the surgeon works to repair a hernia from an iatrogenic hole dissected to access the hernia sac that is then primarily closed. A TEPP avoids the peritoneum altogether by staying superficial to it to access the hernia sac and repair it.[5]

Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (HIPEC)

A new way to manage malignancies that have originated or widely metastasized to the peritoneum is being investigated.[6] The concept behind HIPEC is to directly administer chemotherapy to the peritoneal surface in the hopes of widely reducing tumor burden. Prior to the advent of HIPEC, surgery was utilized to resect involved areas but was not feasible when widely disseminated, conferring a poor prognosis for the patient. While still requiring extensive research, there is hope that HIPEC will be a new tool for surgeons to use in the battle against cancer.

Adhesions

Anything that injures the peritoneum, such as infection, trauma, or surgery can cause scar formation. This scar formation is referred to as adhesions and has this name because the formation can lead to pathologic attachments between structures. This can be problematic as it can lead to small or large bowel obstructions and serve as a nidus for volvulus.[7]

FAST Exam

In trauma situations, it is important to assess free intraperitoneal fluid in the abdomen in a time-efficient manner to help determine if the patient will need emergent surgery. Spaces in the peritoneum can often house large amounts of blood and are therefore important to critically assess. A noninvasive way to accomplish this is the Focused Assessment with Sonographic Trauma (FAST) scan, which is the utilization of ultrasound to assess for fluid in four windows where fluid can accumulate.[8] The four locations are the: hepatorenal recess (also known as Morrison's pouch), splenorenal recess, the pelvis, and pericardium. A positive result as signified by an anechoic region representing fluid in any of these areas in the setting of hemodynamic instability suggests that the patient undergo emergency surgery to localize and stop the bleed and repair any other injury.

Peritoneal Closure

Any major defect in the peritoneum is classically closed using slowly absorbable monofilament sutures if the closure can be performed. However, recent research has indicated that non-closure of the peritoneum may be associated with better outcomes. Some studies have indicated that peritoneal defects in open appendectomy, caesarian section, gastric bypass, and more may be avoided in certain conditions. For example, non-closure of the peritoneum was recommended in c-section patients who have renal insufficiency or hypertensive disorders. This is an area of developing research that may guide future practice.[9][10][11][12]

Clinical Significance

Peritonitis

The peritoneum is of significant clinical importance. The peritoneum can develop inflammation that can present as peritonitis. The condition is often associated with perforation of the intestinal viscera and florid infection. Other causes of peritonitis include free blood, gastric and pancreatic juices, medications, and chemicals in the peritoneal cavity. Peritonitis may be localized or diffuse and often presents with signs of an acute abdomen, such as rigidity, rebound tenderness, or guarding. Treatment depends on the cause. All perforations need surgical treatment. Infections need to be treated with antibiotics. Mortality is highest in elderly patients.

Ascites

Normally, the peritoneal space only contains up to 100 mL of serous fluid. In various situations, such as cirrhosis or chyle leaks, there can be a pathologic increase in peritoneal fluid volume. Cirrhotic ascites is believed to be due to portal hypertension, leading to increased permeability in blood vessels, allowing for altered oncotic and hydrostatic pressures that result in an imbalance of protein and electrolytes, thus altering the fluid flow.[13] In chylous ascites, there is an increase in lymphatic fluid in the peritoneal cavity, which can be secondary to a chyle leak or can occur from surgery or trauma.[14] Treatment is primarily medical but can be surgical on occasion.

Peritoneal Dialysis Infusion of a hypertonic fluid in the peritoneal cavity performs peritoneal dialysis. Once the waste products are absorbed, the fluid is then drained out. Several cycles are performed each time. The most common complication of peritoneal dialysis is the risk of infection. Another complication that is not rare is a perforation of bowel when the dialysis catheter is inserted inside the peritoneal cavity.

Malignancy

The peritoneal cavity is sometimes affected by malignancy of which the most common is mesothelioma. In addition, cancer can metastasize resulting in peritoneal carcinomatosis. A rarer manifestation of cancer presenting in the peritoneum is pseudomyxoma peritonei, which is believed to be a cancer of appendiceal or colon origin. Treatment is primarily surgical to resect involved areas.

Hydrocephalus

The peritoneum is also utilized in therapeutic approaches for hydrocephalus. Patients who want definitive treatment for their hydrocephalus or are refractory to medical management can pursue surgical management via a ventriculoperitoneal shunt where the excess cerebrospinal fluid is shunted to the peritoneum, where it is then reabsorbed by the body more appropriately.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

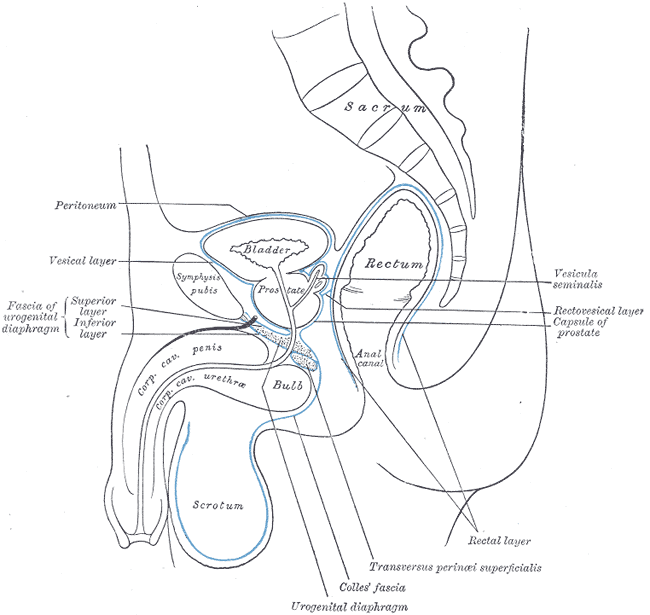

Median Sagittal Section of Male Pelvis Anatomy. Anatomy includes pelvis, sacrum, peritoneum, vesical layer, fascia of urogenital diaphragm, superior and inferior layer, bladder, prostate, symphysis pubis, rectum, anal canal, corpus cavernosum penis and urethra, bulb, scrotum, urogenital diaphragm, Colles fascia, transversus perinei superficialis, rectal layer, vesicula seminalis, rectovesical layer, and capsule of prostate.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Pannu HK, Oliphant M. The subperitoneal space and peritoneal cavity: basic concepts. Abdominal imaging. 2015 Oct:40(7):2710-22. doi: 10.1007/s00261-015-0429-5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26006061]

Blackburn SC, Stanton MP. Anatomy and physiology of the peritoneum. Seminars in pediatric surgery. 2014 Dec:23(6):326-30. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2014.06.002. Epub 2014 Jun 4 [PubMed PMID: 25459436]

Solass W, Horvath P, Struller F, Königsrainer I, Beckert S, Königsrainer A, Weinreich FJ, Schenk M. Functional vascular anatomy of the peritoneum in health and disease. Pleura and peritoneum. 2016 Sep 1:1(3):145-158. doi: 10.1515/pp-2016-0015. Epub 2016 Oct 4 [PubMed PMID: 30911618]

Sheehan D. The Afferent Nerve Supply of the Mesentery and its Significance in the Causation of Abdominal Pain. Journal of anatomy. 1933 Jan:67(Pt 2):233-49 [PubMed PMID: 17104420]

Yang XF, Liu JL. Anatomy essentials for laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Annals of translational medicine. 2016 Oct:4(19):372 [PubMed PMID: 27826575]

Salti GI, Naffouje SA. Feasibility of hand-assisted laparoscopic cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal surface malignancy. Surgical endoscopy. 2019 Jan:33(1):52-57. doi: 10.1007/s00464-018-6265-2. Epub 2018 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 29926165]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLoftus TJ, Morrow ML, Lottenberg L, Rosenthal MD, Croft CA, Smith RS, Moore FA, Brakenridge SC, Borrego R, Efron PA, Mohr AM. The Impact of Prior Laparotomy and Intra-abdominal Adhesions on Bowel and Mesenteric Injury Following Blunt Abdominal Trauma. World journal of surgery. 2019 Feb:43(2):457-465. doi: 10.1007/s00268-018-4792-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30225563]

Bloom BA, Gibbons RC. Focused Assessment With Sonography for Trauma. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29261902]

Muysoms FE, Antoniou SA, Bury K, Campanelli G, Conze J, Cuccurullo D, de Beaux AC, Deerenberg EB, East B, Fortelny RH, Gillion JF, Henriksen NA, Israelsson L, Jairam A, Jänes A, Jeekel J, López-Cano M, Miserez M, Morales-Conde S, Sanders DL, Simons MP, Śmietański M, Venclauskas L, Berrevoet F, European Hernia Society. European Hernia Society guidelines on the closure of abdominal wall incisions. Hernia : the journal of hernias and abdominal wall surgery. 2015 Feb:19(1):1-24. doi: 10.1007/s10029-014-1342-5. Epub 2015 Jan 25 [PubMed PMID: 25618025]

Kurek Eken M, Özkaya E, Tarhan T, İçöz Ş, Eroğlu Ş, Kahraman ŞT, Karateke A. Effects of closure versus non-closure of the visceral and parietal peritoneum at cesarean section: does it have any effect on postoperative vital signs? A prospective randomized study. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstetricians. 2017 Apr:30(8):922-926. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2016.1190826. Epub 2016 Sep 5 [PubMed PMID: 27187047]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBektasoglu HK, Hasbahceci M, Yigman S, Yardimci E, Kunduz E, Malya FU. Nonclosure of the Peritoneum during Appendectomy May Cause Less Postoperative Pain: A Randomized, Double-Blind Study. Pain research & management. 2019:2019():9392780. doi: 10.1155/2019/9392780. Epub 2019 May 23 [PubMed PMID: 31249637]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceStenberg E, Szabo E, Ågren G, Ottosson J, Marsk R, Lönroth H, Boman L, Magnuson A, Thorell A, Näslund I. Closure of mesenteric defects in laparoscopic gastric bypass: a multicentre, randomised, parallel, open-label trial. Lancet (London, England). 2016 Apr 2:387(10026):1397-1404. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01126-5. Epub 2016 Feb 16 [PubMed PMID: 26895675]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePericleous M, Sarnowski A, Moore A, Fijten R, Zaman M. The clinical management of abdominal ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and hepatorenal syndrome: a review of current guidelines and recommendations. European journal of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2016 Mar:28(3):e10-8. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000548. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26671516]

Mandavdhare HS, Sharma V, Singh H, Dutta U. Underlying etiology determines the outcome in atraumatic chylous ascites. Intractable & rare diseases research. 2018 Aug:7(3):177-181. doi: 10.5582/irdr.2018.01028. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30181937]