Introduction

Peripheral nerve injury can vary wildly in severity and presentation, ranging from mild soreness to severe muscle weakness. Axillary nerve injuries typically respond well to conservative management, though a surgical intervention may be required. Failure to accurately diagnose and manage patients may lead to life-long disability that can affect the overall quality of life. While axillary nerve lesions are somewhat rare, they should be considered when patients present with shoulder weakness and sensory loss.

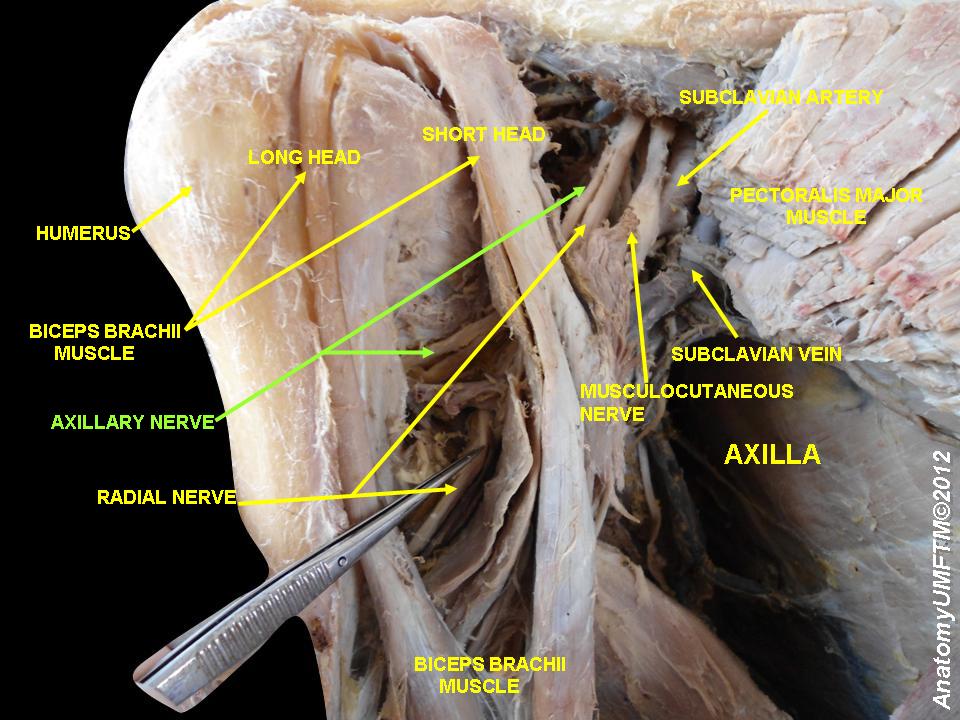

Anatomic Course

The axillary nerve diverges from the posterior cord of the brachial plexus anterior to the subscapularis muscle, running posterior to the axillary artery. It then travels inferior to the glenohumeral joint capsule and passes through the quadrangular space with the posterior humeral circumflex artery. The axillary nerve proceeds to split into anterior and posterior divisions. The anterior division supplies motor innervation to the anterior and middle heads of the deltoid. The posterior division provides motor innervation to the posterior deltoid and teres minor before eventually terminating as the superior lateral cutaneous nerve and innervating the lateral shoulder.[1] The axillary nerve is a bilateral upper extremity peripheral nerve and receives significant contributions from C5 and minor contributions from C6.[2]

Functional Anatomy

As stated above, the axillary nerve innervates the deltoid and teres minor muscles. The deltoid muscle, divided into three parts, performs and assists in a variety of actions. The primary function of the deltoid muscle is glenohumeral abduction, performed by the middle muscle belly. The anterior muscle belly assists in glenohumeral flexion and internal rotation. The posterior muscle belly assists in glenohumeral extension and external rotation.[3] The teres minor functions in glenohumeral external rotation.[4] The deltoid and teres minor stabilize the glenohumeral joint, with the teres minor contributing a greater role as a part of the glenohumeral rotator cuff.[5] Lastly, the axillary nerve transmits afferent sensory input from the lateral shoulder.[1] Several studies have claimed the axillary nerve innervates the long head of the triceps brachii. Still, a recent cadaver study by Wade et al. showed no axillary nerve innervation to the triceps brachii.[6]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Axillary nerve injury typically presents with other brachial plexopathies. Axillary neuropathies are due to traumatic injuries, traction injuries, quadrilateral space syndrome, and brachial neuritis (also called neuralgic amyotrophy or Parsonage-Turner syndrome).[3]

An anterior dislocation and forced abduction of the shoulder joint appear to be common causes of axillary nerve injury in young people.

Epidemiology

An axillary nerve mononeuropathy is a rare event, occurring in about 0.3 to 6% of all brachial plexus injuries.[2] Axillary nerve injuries constitute 6% to 10% of all brachial plexus injuries during shoulder surgery.[7] Recent research showed that the risk of axillary nerve injury after glenohumeral dislocation increased with age. Approximately 65% of patients over 40 were diagnosed by electromyography (EMG) with an axillary nerve lesion.[8] Brachial neuritis has an estimated incidence of 1 to 3 per 100,000 annually with a female predilection.[9]

Pathophysiology

The axillary nerve injury may occur due to over-stretching of the axillary nerve during anterior should dislocation. The axillary nerve is most susceptible to injury at the origin from the posterior cord, in the quadrilateral space, the anteroinferior aspect of the shoulder capsule, and within the subfascial surface of the deltoid muscle.

History and Physical

The principle presenting symptoms are a weakness in glenohumeral abduction with or without numbness to the lateral shoulder area. Patients may also present with weakness in glenohumeral external rotation; however, this may not be apparent due to the ability of the infraspinatus. In patients presenting after dislocation or fracture, signs of trauma will be evident on physical exam. During external rotation and abduction, one may note the weakness of the deltoid and teres minor muscles.

Nevertheless, patients may not report muscle weakness or paresthesia due to acute pain and limited range of motion.[2] A compressive neuropathy may occur after blunt trauma to the deltoid muscle. Atraumatic neuropathy preceded by localized pain presents in brachial neuritis.[2][10] Patients with quadrilateral space syndrome (QSS) present with vascular symptoms such as cyanosis and pallor of the distal upper extremity and splinter hemorrhages in addition to neurologic symptoms.[11]

Evaluation

A proper history is essential in determining the correct intervention necessary. At the very least, the provider should obtain information on symptom onset, palliative and provoking factors, quality of the symptoms, radiation of symptoms to other regions, the severity of pain (if applicable), and timing. Key questions to consider are trauma, focal weakness, numbness and tingling, cyanosis, limitations in the range of motion, and pain.

The physical exam should begin with a visual inspection of the upper extremity, noting the presence or absence of trauma. The provider should palpate the ipsilateral neck and upper extremity for tenderness and muscle tone, followed by evaluating passive and active ranges of motion. Next, a neurologic exam focused on the axillary nerve and shoulder should also include assessing the spinal accessory, suprascapular, long thoracic, musculocutaneous, and radial nerves.[2] Several specialty clinical tests that evaluate the deltoid and teres minor muscles exist that may guide providers during assessment for axillary nerve injury in the absence of trauma, muscle strain, or known tendinopathies. The swallow-tail, deltoid extension lag, and Bertelli tests have been used to examine deltoid muscle weakness.[12][13] The external rotation lag, drop arm, and Patte tests evaluate the function of the teres minor muscle.[14]

Radiographs of the shoulder can help identify fractures involving the shoulder region after traumatic events. Shoulder magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be ordered if compressive neuropathy or inflammatory processes are suspected or in cases of chronic neuropathy that has resulted in muscle atrophy. The gold standard for diagnosis confirmation is EMG. Additionally, EMG findings can help establish a patient's baseline to evaluate recovery.[2]

Treatment / Management

Most axillary nerve injuries are treatable conservatively; however, select cases should require surgical management. For atraumatic injuries, a baseline EMG should occur within 1 month, and treatment with physical therapy (PT) should begin. In traumatic shoulder injury involving the axillary nerve, most patients may recover with non-operative treatment; however, there is the possibility of permanent paralysis. In many cases, then the shoulder is reduced, the need for surgical intervention is minimal. The reduced shoulder is immobilized for 4-6 weeks (young patients) or 7-10 days (elderly). This is then followed by extensive rehabilitation to regain muscle strength and shoulder mobility.

Surgical intervention can be considered in closed trauma if EMG shows no improvement after 3 months; however, acute nerve lesions warrant expedited surgical management. Neurorrhaphy, neurolysis, and nerve grafting are all possible surgical options. In patients with chronic muscle atrophy, muscle transfer may be a therapeutic option.[2]

For patients with neuropraxia, full recovery occurs over 6-12 months. The muscle weakness spontaneously recovers without any specific treatment.

For those with axonotmesis, the recovery rates are about 70% to 80% and often take many months. The patient should be followed with serial electromyogram (EMG) studies to assess for regeneration. If by 6-9 months, there are no signs of recovery, surgical exploration may be considered.

For those with neurotmesis, there is never any recovery without surgical intervention.

Differential Diagnosis

The following should be potential differentials when considering an axillary nerve lesion:[2][15]

- Cervical radiculopathy

- Thoracic outlet syndrome

- Rotator cuff tear

- Brachial plexopathy

- Quadrilateral space syndrome

- Brachial neuritis

- Glenohumeral fracture/dislocation

- Subacromial impingement syndrome

- Herpes zoster

Prognosis

Most injuries to the axillary nerve are considered low-grade following glenohumeral dislocation and will often result in complete recovery within 7 months.[8] A systematic review showed 85% of nerve graft patients and 79% of nerve transfer patients reached muscle strength grades 4/5 or greater at 18 to 24 months post-op.[16]

Complications

Chronic axillary nerve lesions result in permanent numbness to the lateral shoulder region, atrophy of the deltoid and teres minor muscles, and possibly chronic neuropathic pain.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Rehabilitation Care:

Frizziero et al. developed a rehabilitation protocol for axillary nerve injury which divides into two phases over two months. The initial phase focused on the restoration of scapular kinesis, glenohumeral stabilization, and strengthening of the deltoid muscle. The second phase focused on a return to function with particular attention to motor, postural, and proprioceptive control.[17]

Deterrence and Patient Education

- The axillary nerve is the most common damaged nerve in glenohumeral dislocation

- Low-grade axillary nerve injuries should resolve within 12 weeks

- High-grade axillary nerve injuries require surgical intervention

- Athletes in contact sports are at an increased risk of axillary nerve injury by traumatic processes that result in compression and lesion

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Injury to the axillary nerve is a serious and common complication of glenohumeral dislocation. Complex dislocations (those associated with secondary injury to other bones, nerves, vessels, or tendons) should be identified as soon as possible by the primary care provider and nurse practitioner to minimize long-term deficits. Studies have shown an increased risk of axillary nerve injuries if dislocations have not been reduced within 12 hours. If prolonged axillary nerve deficits persist, surgical intervention is required, with better results seen with early intervention.[8] Iatrogenic axillary nerve injury is also commonly reported during surgical osteosynthesis, especially when utilizing the anterolateral approach.[19] Koshy et al. found no significant differences in post-op muscle strength recovery to 4/5 between patients undergoing surgical nerve transfers versus nerve grafting.[16]

Management of axillary nerve injuries is best with an interprofessional team, including physicians/mid-level practitioners, nursing, and physical therapists. In cases where medication is part of the regimen, pharmacists as well.

Media

References

Isaacs J, Cochran AR. Nerve transfers for peripheral nerve injury in the upper limb: a case-based review. The bone & joint journal. 2019 Feb:101-B(2):124-131. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.101B2.BJJ-2018-0839.R1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30700118]

Steinmann SP, Moran EA. Axillary nerve injury: diagnosis and treatment. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2001 Sep-Oct:9(5):328-35 [PubMed PMID: 11575912]

Moser T, Lecours J, Michaud J, Bureau NJ, Guillin R, Cardinal É. The deltoid, a forgotten muscle of the shoulder. Skeletal radiology. 2013 Oct:42(10):1361-75. doi: 10.1007/s00256-013-1667-7. Epub 2013 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 23784480]

Williams MD, Edwards TB, Walch G. Understanding the Importance of the Teres Minor for Shoulder Function: Functional Anatomy and Pathology. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2018 Mar 1:26(5):150-161. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00258. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29473831]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWheelock M, Clark TA, Giuffre JL. Nerve Transfers for Treatment of Isolated Axillary Nerve Injuries. Plastic surgery (Oakville, Ont.). 2015 Summer:23(2):77-80 [PubMed PMID: 26090346]

Wade MD, McDowell AR, Ziermann JM. Innervation of the Long Head of the Triceps Brachii in Humans-A Fresh Look. Anatomical record (Hoboken, N.J. : 2007). 2018 Mar:301(3):473-483. doi: 10.1002/ar.23741. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29418118]

Bokor DJ, Raniga S, Graham PL. Axillary Nerve Position in Humeral Avulsions of the Glenohumeral Ligament. Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine. 2018 Dec:6(12):2325967118811044. doi: 10.1177/2325967118811044. Epub 2018 Dec 5 [PubMed PMID: 30547041]

Avis D, Power D. Axillary nerve injury associated with glenohumeral dislocation: A review and algorithm for management. EFORT open reviews. 2018 Mar:3(3):70-77. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.3.170003. Epub 2018 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 29657847]

Van Eijk JJ, Groothuis JT, Van Alfen N. Neuralgic amyotrophy: An update on diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment. Muscle & nerve. 2016 Mar:53(3):337-50. doi: 10.1002/mus.25008. Epub 2016 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 26662794]

Seror P. Neuralgic amyotrophy. An update. Joint bone spine. 2017 Mar:84(2):153-158. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2016.03.005. Epub 2016 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 27263426]

Sato T, Tsai TL, Altamimi A, Tsai TM. Quadrilateral Space Syndrome: A Case Report. The journal of hand surgery Asian-Pacific volume. 2017 Mar:22(1):125-127. doi: 10.1142/S0218810417720108. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28205489]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBertelli JA, Ghizoni MF. Abduction in internal rotation: a test for the diagnosis of axillary nerve palsy. The Journal of hand surgery. 2011 Dec:36(12):2017-23. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.09.011. Epub 2011 Nov 3 [PubMed PMID: 22051233]

Werthel JD, Bertelli J, Elhassan BT. Shoulder function in patients with deltoid paralysis and intact rotator cuff. Orthopaedics & traumatology, surgery & research : OTSR. 2017 Oct:103(6):869-873. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2017.06.008. Epub 2017 Jul 10 [PubMed PMID: 28705650]

Collin P, Treseder T, Denard PJ, Neyton L, Walch G, Lädermann A. What is the Best Clinical Test for Assessment of the Teres Minor in Massive Rotator Cuff Tears? Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2015 Sep:473(9):2959-66. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4392-9. Epub 2015 Jun 12 [PubMed PMID: 26066066]

Aktas I, Akgun K, Gunduz OH. Axillary mononeuropathy after herpes zoster infection mimicking subacromial impingement syndrome. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation. 2008 Oct:87(10):859-61. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e318186bb95. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18806513]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKoshy JC, Agrawal NA, Seruya M. Nerve Transfer versus Interpositional Nerve Graft Reconstruction for Posttraumatic, Isolated Axillary Nerve Injuries: A Systematic Review. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2017 Nov:140(5):953-960. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000003749. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29068931]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFrizziero A, Vittadini F, Del Felice A, Creta D, Ferlito E, Gasparotti R, Masiero S. Conservative treatment after axillary nerve re-injury in a rugby player: a case report. European journal of physical and rehabilitation medicine. 2019 Aug:55(4):510-514. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.18.05165-1. Epub 2018 Dec 21 [PubMed PMID: 30574734]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePerlmutter GS, Leffert RD, Zarins B. Direct injury to the axillary nerve in athletes playing contact sports. The American journal of sports medicine. 1997 Jan-Feb:25(1):65-8 [PubMed PMID: 9006694]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKongcharoensombat W, Wattananon P. Risk of Axillary Nerve Injury in Standard Anterolateral Approach of Shoulder: Cadaveric Study. Malaysian orthopaedic journal. 2018 Nov:12(3):1-5. doi: 10.5704/MOJ.1811.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30555639]