Introduction

Although testicular cancers are relatively rare, accounting for only 1% to 2% of worldwide male cancer diagnoses, it is the most common malignancy in men aged 15 to 44.[1][2] Testicular tumors may originate from any of the cell types present in the testes and generally fall into the two competing categories of germ cell tumors, of which about 95% of testicular cancer is composed, and sex cord-stromal tumors which comprise the remaining 5% in adults.[3]

Of the 5% of sex cord-stromal tumors, Leydig cell tumors are the most common and derive from the same Leydig cells that normally reside in the interstitium of testicles and secrete testosterone in the presence of luteinizing hormone. They are generally benign tumors with only 5% to 10% being considered malignant and have a bimodal distribution with peaks in the prepubertal age group and between the ages of 30 to 60.[3][4] Due to Leydig cells' hormonally active properties, they can present with precocious puberty, breast tenderness, or gynecomastia.[5]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Leydig cell tumors derive from Leydig cells, which are histologically packed between the seminiferous tubules of the testis and are physiologically responsible for testosterone secretion in response to luteinizing hormone.

Epidemiology

As a rare subtype of a rare tumor, Leydig cell tumors had traditionally been considered a very infrequent diagnosis, comprising only 1% to 3% of total testicular tumors removed each year.[6][7][8]

Interestingly, more contemporary data sets have questioned the rarity of Leydig cell tumors and have found them to be a potentially more common entity with estimates of the tumor incidence being anywhere from 14% to 22% of all surgically removed testicular cancer.[9] Potential reasons for this include the increasing use of improved ultrasound technology, leading to increased detection of small nodules that have not previously detected historical series.[9]

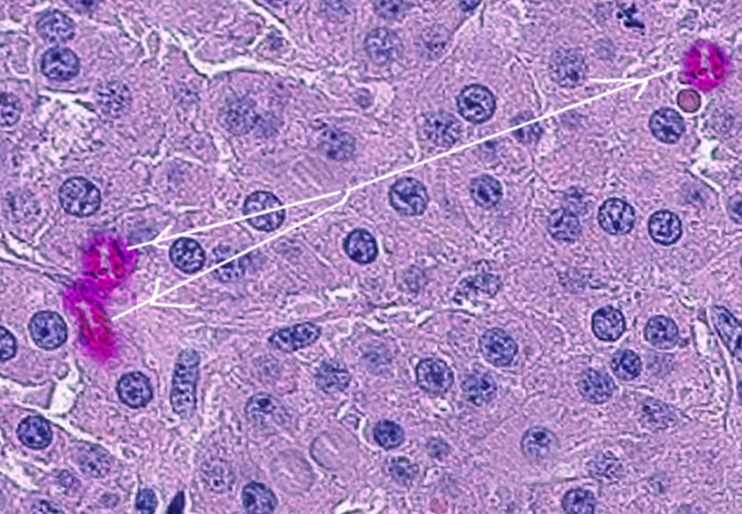

Histopathology

The mass usually reveals a well-circumscribed lesion in the testis. The cut surface of the mass shows a distinct golden brown or homogeneous yellow to light brown appearance. Microscopically, the tumor cells are large to polygonal with a round to oval nucleus and deeply acidophilic with granular cytoplasm. The cytoplasm also shows rod-shaped crystals referred to as "crystalloids of Reinke," which appear in 35% of tumors, and lipofuscin pigment in a smaller percent (10% to 15%).

History and Physical

Like other tumors of the testicle, painless swelling of a testicle is the single most common presentation of Leydig cell tumors.[10] Painless testicular swelling is the clinical presentation in about 50% of patients eventually diagnosed with testicular cancer.[11] A complete physical exam should include palpation of both the affected and contralateral testicle, making an important note of relative size and firmness as well as any distinct intrinsic or extrinsic testicular masses. Hydroceles also present as painless testicular swelling, but it is critical to keep in mind that this benign pathology may accompany a testicular tumor and could reduce the ability to identify a mass on physical exam.

Unique to Leydig cell tumors, however, are patients presenting with conspicuous clinical manifestations owing to the tumor’s propensity to secrete androgens or (less commonly) estrogen, directly or by peripheral conversion of testosterone.[5]

In prepubertal patients, this can present as precocious puberty, including early development of pubic hair as well as penile and musculoskeletal growth beyond that expected for the child’s age.

Interestingly, the physiologic effects of the elevated levels of circulating androgens in postpubertal men are usually clinically unnoticeable. Therefore, the most common hormone-related presentation of a man with a Leydig cell tumor is gynecomastia.[4] Other literature reported presentations to include breast tenderness, reduced libido, erectile dysfunction, azoospermia, primary infertility, or even Cushing syndrome.[12][13][14][15][16][17]

Evaluation

Due to the ubiquity and relative inexpensiveness of ultrasonography, any patient presenting with testicular swelling, hydrocele, or scrotal signs or symptoms of unclear etiology should receive a scrotal ultrasound. Unexplained infertility, precocious puberty, or gynecomastia should also prompt scrotal ultrasonography as well as elevated serum androgens or estrogens on labwork without an identifiable source.

If a Leydig cell tumor is present, it will be identified on scrotal ultrasound as an intratesticular mass and sonographically indistinguishable from a more commonly malignant germ cell tumor. An intratesticular mass should be considered cancer unless proven otherwise. When malignancy is likely, tumor markers should be drawn, including alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), quantitative beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-HCG), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). At this point, staging and further work-up may be necessary after a radical inguinal orchiectomy.

Treatment / Management

After drawing tumor markers, the treatment of an intratesticular mass is a radical inguinal orchiectomy. Rarely is there a role for biopsy before orchiectomy unless exceptional circumstances exist, such as a solitary testis with mass. Prior to orchiectomy, patients should receive counsel on sperm banking. Radical orchiectomy should take place through an inguinal incision to avoid leaving the inguinal portion of the spermatic cord or altering the lymphatic drainage in the setting of a potentially malignant tumor. The clinician should consider an inguinal biopsy of the contralateral testicle if scrotal ultrasound demonstrates a suspicious mass or marked atrophy or if there exists a clinical history of cryptorchidism on that side.

Some authors have proposed Leydig cell tumors to be an ideal testicular tumor for testis-sparing surgery.[10] In these cases, preoperative tumor markers should all be within the normal range, a suspicion of a Leydig cell tumor should be clinically evident (gynecomastia, elevated testosterone or estrogen, infertility, etc.), the tumor should be less than 2.5 cm in size and frozen section should be obtained after spermatic cord clamping confirming a Leydig cell tumor. With these parameters, the authors have reported no relapse in 29 patients who underwent testis-sparing surgery and received a pathologic diagnosis of Leydig cell tumor.[10] Nevertheless, the rarity of Leydig cell tumors and the similar clinical presentation and ultrasound appearance to germ cell tumors mean that most patients eventually diagnosed with Leydig cell tumors undergo initial inguinal radical orchiectomy.

While the majority of Leydig cell tumors are benign and orchiectomy curative, post-orchiectomy surveillance is still a recommendation. However, primarily because of the limited number of cases, there exist no widely accepted protocols for follow-up.[18] Patients require monitoring at regular intervals for at least the first two years after diagnosis; most patients with Leydig cell tumors that do metastasize, do so within the first two years.[19] These appointments should include a physical exam, hormonal profile (luteinizing hormone [LH], follicle-stimulating hormone [FSH], testosterone, estrogen, and estradiol), germ cell tumor markers (beta-HCG, AFP, LDH) and cross-sectional imaging of the chest, abdomen and pelvis every 6 months for the first 2 years.[19](B3)

Malignant behavior of Leydig cell tumors is exhibited by metastasis to the retroperitoneal lymph nodes, liver, lungs, and bone.[4] If metastatic disease does occur, it responds poorly to chemotherapy or radiation, leaving surgical resection (retroperitoneal lymph node dissection or RPLND) as the only treatment capable of rendering patients disease-free.[18](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

Several differential diagnoses may be compiled depending on where in the clinical presentation or work-up a provider finds themself.

If a patient is presenting with gynecomastia:

- Drug side effect (ACE inhibitor, marijuana, spironolactone, etc…)

- Obesity

- Hyperthyroidism

- Liver disease

- Klinefelter syndrome

- Adrenal tumor

If a patient is presenting with hypogonadism:

- Primary hypogonadism (Klinefelter syndrome, testicular trauma/radiation/infection)

- Secondary hypogonadism (prolactin-secreting pituitary tumor, Kallman syndrome, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism)

Upon identifying an intratesticular mass via scrotal ultrasound, the differential diagnosis includes:

- Germ cell tumor (seminoma, teratoma, yolk sac tumor, embryonal carcinoma, choriocarcinoma)

- Non-germ cell tumor (Sertoli cell tumor, granulosa cell tumor, gonadoblastoma)

- Intratesticular hematoma

Prognosis

Orchiectomy alone is curative in patients with benign Leydig cell tumors.[20] The cancer-specific mortality for Leydig cell tumors is 2%, with an overall 5-year survival of greater than 90% after orchiectomy.[21][22] Malignant Leydig cell tumors are variable with the survival of patients with metastases ranging from 2 months to 17 years with a median of 2 years.[5] Interestingly, in those who present initially with hypogonadism, Leydig cell dysfunction may continue even after the removal of the tumor and 40% of men may require testosterone replacement therapy postoperatively.[23]

Complications

Complications from the disease itself arise mostly from delays in diagnosis and treatment; this may manifest itself as any or all of the symptoms described in detail above, including gynecomastia, infertility, hypogonadism, or erectile dysfunction. Delayed treatment of malignant Leydig cell tumors may result in metastasis and death.

Unfortunately, delay in the diagnosis of testicular cancer is a well-known entity with a mean delay to diagnosis cited as 26 weeks.[11] Patient-mediated delays are mainly due to ignorance, embarrassment, fear of cancer, or fear of emasculation.[24] Physician-mediated delay is most commonly due to the misdiagnosis of a testis tumor as an infection.[11]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Invaluable information for patients diagnosed with Leydig cell tumors includes the fact that a large majority of these tumors are benign, and orchiectomy is curative in most cases. Early detection and removal can be vital for fertility due to the detrimental effects of long-term estrogen exposure.[25] It is also essential for patients to know that even after tumor excision, 40% of men presenting with hypogonadism may still require testosterone replacement therapy postoperatively.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Testicular cancer, overall, is a relatively rare tumor comprising only 1 to 2% of worldwide male cancer diagnoses. Of testicular cancer, Leydig cell tumors have historically been considered a rare subtype, comprising only 1% to 3% of total testicular masses removed annually. Some recent publications, however, have called into question the historicity of Leydig cell tumors as a rare diagnosis citing rates as high as 14% to 22% of all surgically removed testicular cancer.

- Leydig cell tumors have a bimodal distribution, with an initial peak in the prepubertal age group, 4 to 10, and then a second peak between the ages of 30 and 60.

- Leydig cell tumors, like other testicular tumors, most commonly present as a painless testicular mass or swelling.

- Unique to the hormonally active nature of Leydig cell tumors, patients may present with symptoms of gynecomastia, breast tenderness, precocious puberty, infertility, hypogonadism, or erectile dysfunction. The most common of these in adult patients is gynecomastia due to the conversion of excess (unregulated) testosterone to estradiol by aromatase.

- Radical orchiectomy alone is generally curative for clinically benign Leydig cell tumors.

- Testis-sparing surgery can be a consideration if the clinical suspicion of Leydig cell tumor is high, pre-operative testicular tumor marker levels are within normal limits, and the tumor size is less than 2.5 cm. An intra-operative frozen section should always be obtained, and a radical orchiectomy performed if malignant.

- Leydig cell tumors demonstrate malignancy by metastasizing. Approximately 10% of Leydig cell tumors in adults exhibit malignant behavior.

- The only treatment for malignant Leydig cell tumors is retroperitoneal lymph node dissection, as they are resistant to chemotherapy and radiation.

- There are no reported cases of malignant Leydig cell tumors in the pediatric population.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

As described above, the diagnosis and management of Leydig cell tumors can be particularly challenging, especially given the relative rarity of the tumor and extremely variable presentation. Generally, the longer the delay in diagnosis, the worse the outcomes, so an interprofessional healthcare team is the best method for diagnosis and management of suspected Leydig cell tumors. Because of this, primary care and emergency department providers should consider ultrasound as an extension of a physical exam for any patient with testicular swelling or unexplained scrotal pain and should refer patients with questionable or concerning ultrasound results to a urologist for further work-up and therapy. Likewise, primary care providers or endocrinologists should consider Leydig cell tumors in the differential diagnosis of infertility, hypogonadism, and especially gynecomastia. Urology and oncology specialty-trained nursing staff can be a valuable asset throughout the diagnosis and management of these tumors, providing patient counsel, assisting during procedures, and helping to followup and assess treatment effectiveness. While the oncologist may be at the head of the team, the entire interprofessional team needs to coordinate care for optimal patient results. [Level 5]

As with all malignancies, the earlier the diagnosis, the better the outcome.

Media

References

Park JS, Kim J, Elghiaty A, Ham WS. Recent global trends in testicular cancer incidence and mortality. Medicine. 2018 Sep:97(37):e12390. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012390. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30213007]

Rosen A, Jayram G, Drazer M, Eggener SE. Global trends in testicular cancer incidence and mortality. European urology. 2011 Aug:60(2):374-9. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.05.004. Epub 2011 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 21612857]

Mooney KL, Kao CS. A Contemporary Review of Common Adult Non-germ Cell Tumors of the Testis and Paratestis. Surgical pathology clinics. 2018 Dec:11(4):739-758. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2018.07.002. Epub 2018 Oct 17 [PubMed PMID: 30447839]

Jou P, Maclennan GT. Leydig cell tumor of the testis. The Journal of urology. 2009 May:181(5):2299-300. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.02.051. Epub 2009 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 19303105]

Al-Agha OM, Axiotis CA. An in-depth look at Leydig cell tumor of the testis. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2007 Feb:131(2):311-7 [PubMed PMID: 17284120]

Masur Y, Steffens J, Ziegler M, Remberger K. [Leydig cell tumors of the testis--clinical and morphologic aspects]. Der Urologe. Ausg. A. 1996 Nov:35(6):468-71 [PubMed PMID: 9064885]

Carmignani L, Gadda F, Gazzano G, Nerva F, Mancini M, Ferruti M, Bulfamante G, Bosari S, Coggi G, Rocco F, Colpi GM. High incidence of benign testicular neoplasms diagnosed by ultrasound. The Journal of urology. 2003 Nov:170(5):1783-6 [PubMed PMID: 14532776]

Carmignani L, Salvioni R, Gadda F, Colecchia M, Gazzano G, Torelli T, Rocco F, Colpi GM, Pizzocaro G. Long-term followup and clinical characteristics of testicular Leydig cell tumor: experience with 24 cases. The Journal of urology. 2006 Nov:176(5):2040-3; discussion 2043 [PubMed PMID: 17070249]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLeonhartsberger N, Ramoner R, Aigner F, Stoehr B, Pichler R, Zangerl F, Fritzer A, Steiner H. Increased incidence of Leydig cell tumours of the testis in the era of improved imaging techniques. BJU international. 2011 Nov:108(10):1603-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10177.x. Epub 2011 Jun 1 [PubMed PMID: 21631694]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSuardi N, Strada E, Colombo R, Freschi M, Salonia A, Lania C, Cestari A, Carmignani L, Guazzoni G, Rigatti P, Montorsi F. Leydig cell tumour of the testis: presentation, therapy, long-term follow-up and the role of organ-sparing surgery in a single-institution experience. BJU international. 2009 Jan:103(2):197-200. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08016.x. Epub 2008 Oct 6 [PubMed PMID: 18990169]

Moul JW. Timely diagnosis of testicular cancer. The Urologic clinics of North America. 2007 May:34(2):109-17; abstract vii [PubMed PMID: 17484916]

Markou A, Vale J, Vadgama B, Walker M, Franks S. Testicular leydig cell tumor presenting as primary infertility. Hormones (Athens, Greece). 2002 Oct-Dec:1(4):251-4 [PubMed PMID: 17018455]

Hekimgil M, Altay B, Yakut BD, Soydan S, Ozyurt C, Killi R. Leydig cell tumor of the testis: comparison of histopathological and immunohistochemical features of three azoospermic cases and one malignant case. Pathology international. 2001 Oct:51(10):792-6 [PubMed PMID: 11881732]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZeuschner P, Veith C, Linxweiler J, Stöckle M, Heinzelbecker J. Two Years of Gynecomastia Caused by Leydig Cell Tumor. Case reports in urology. 2018:2018():7202560. doi: 10.1155/2018/7202560. Epub 2018 Jul 19 [PubMed PMID: 30112247]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePapadimitris C, Alevizaki M, Pantazopoulos D, Nakopoulou L, Athanassiades P, Dimopoulos MA. Cushing syndrome as the presenting feature of metastatic Leydig cell tumor of the testis. Urology. 2000 Jul 1:56(1):153 [PubMed PMID: 10869651]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHibi H, Yamashita K, Sumitomo M, Asada Y. Leydig cell tumor of the testis, presenting with azoospermia. Reproductive medicine and biology. 2017 Oct:16(4):392-395. doi: 10.1002/rmb2.12046. Epub 2017 Jul 20 [PubMed PMID: 29259494]

Keske M, Canda AE, Atmaca AF, Cakici OU, Arslan ME, Kamaci D, Balbay MD. Testis-sparing surgery: Experience in 13 patients with oncological and functional outcomes. Canadian Urological Association journal = Journal de l'Association des urologues du Canada. 2019 Mar:13(3):E83-E88. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.5379. Epub 2018 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 30169152]

Cost NG, Maroni P, Flaig TW. Metastatic relapse after initial clinical stage I testicular Leydig cell tumor. Oncology (Williston Park, N.Y.). 2014 Mar:28(3):211, 214 [PubMed PMID: 24855728]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAcar C, Gurocak S, Sozen S. Current treatment of testicular sex cord-stromal tumors: critical review. Urology. 2009 Jun:73(6):1165-71. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.10.036. Epub 2009 Apr 10 [PubMed PMID: 19362328]

Heer R, Jackson MJ, El-Sherif A, Thomas DJ. Twenty-nine Leydig cell tumors: histological features, outcomes and implications for management. International journal of urology : official journal of the Japanese Urological Association. 2010 Oct:17(10):886-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2010.02616.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20812939]

Banerji JS, Odem-Davis K, Wolff EM, Nichols CR, Porter CR. Patterns of Care and Survival Outcomes for Malignant Sex Cord Stromal Testicular Cancer: Results from the National Cancer Data Base. The Journal of urology. 2016 Oct:196(4):1117-22. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.03.143. Epub 2016 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 27036305]

Osbun N, Winters B, Holt SK, Schade GR, Lin DW, Wright JL. Characteristics of Patients With Sertoli and Leydig Cell Testis Neoplasms From a National Population-Based Registry. Clinical genitourinary cancer. 2017 Apr:15(2):e263-e266. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2016.08.001. Epub 2016 Aug 12 [PubMed PMID: 27594555]

Conkey DS, Howard GC, Grigor KM, McLaren DB, Kerr GR. Testicular sex cord-stromal tumours: the Edinburgh experience 1988-2002, and a review of the literature. Clinical oncology (Royal College of Radiologists (Great Britain)). 2005 Aug:17(5):322-7 [PubMed PMID: 16097561]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOliver RT. Factors contributing to delay in diagnosis of testicular tumours. British medical journal (Clinical research ed.). 1985 Feb 2:290(6465):356 [PubMed PMID: 3917818]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMineur P, De Cooman S, Hustin J, Verhoeven G, De Hertogh R. Feminizing testicular Leydig cell tumor: hormonal profile before and after unilateral orchidectomy. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1987 Apr:64(4):686-91 [PubMed PMID: 3818898]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence