Introduction

In the United States, between 0.4% and 3% of the population identifies as transgender, equating to over 1,000,000 Americans.[1] Not every transgender individual will need or want medical or surgical treatment. Still, given the prevalence of transgender patients in the population, healthcare providers need to be aware of transgender health issues. According to the 2015 United States Transgender Survey, which compiled responses from 28,000 individuals who identify as transgender or gender non-conforming, 33% of respondents reported being mistreated due to gender identity when seeking healthcare. For this reason, healthcare providers who care for transgender patients - and this is a constantly increasing proportion of healthcare providers - must be ready to identify and provide for the needs of these patients. Simply being welcoming, accepting, and non-judgmental is an important first step in building a therapeutic rapport; having an inclusive office in which staff members are trained to ask for patients' preferred pronouns and give their own, and ideally provide gender non-specific restrooms, will make the healthcare environment substantially more trans-friendly.

Transgender patients commonly benefit from behavioral health and endocrine interventions (estrogen and anti-androgen therapy for male to female transitions and testosterone for the female to male), and the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), in its most recent Standards of Care publication (SOC 7, published in 2012), has strongly recommended that patients considering genital surgery ("bottom surgery") have not only a persistent, well-documented history of gender dysphoria but have also completed 12 continuous months of hormonal therapy preoperatively. For chest surgery ("top surgery"), either augmentation or reduction mammoplasty, the WPATH recommends patients have a persistent and well-documented history of gender dysphoria and that patients transitioning from male to female also consider 12 continuous months of feminizing hormone therapy preoperatively. There are no explicit recommendations in SOC 7 for behavioral health documentation or duration of hormonal therapy prior to head and neck surgery, which will focus on this article.

With respect to gender affirmation procedures for the face, the majority of interventions will occur in patients transitioning from male to female, i.e., transgender women. While there are slightly more transgender women than transgender men in the population (33% transgender women, 29% transgender men, 35% non-binary, 3% crossdressers, according to the USTS), the reason that more females require surgery than males is that testosterone therapy typically produces enough changes in secondary sex characteristics of the face (growth of facial hair, thickening of the skin, increase in frontal bossing, lowering of the voice, etc.) that surgery is not necessary.[2][3] In some cases, placement of implants or fat transfer can increase volume in the lower third of the face and contribute to masculinization. Still, the primary area of focus for facial feminization is generally the upper third.[4][5]

Feminization of the upper third of the face often requires several techniques to be applied in combination: the advancement of the hairline, hair transplantation, brow lifting, and reduction of frontal bossing or "frontal cranioplasty."[6][7][8] While the advancement of a scalp flap, hair transplant, and pretrichial brow lifting are commonly-employed cosmetic surgery interventions, frontal cranioplasty bears special consideration. Several methods of reducing the brow's prominence are often described as type 1, 2, and 3 frontal cranioplasties.[9] Type 1 cranioplasty reduces the supraorbital ridge's protrusion, usually using a drill, including decreasing the thickness of the anterior table of the frontal sinus. This technique is the simplest, but it is only effective in patients with either a very thick anterior frontal sinus table or an absent pneumatized frontal sinus. Type 2 cranioplasty involves augmentation of the forehead's convexity using bone cement or methyl methacrylate in addition to a reduction of the supraorbital ridge with a drill. Type 3 cranioplasty is advocated by many prominent facial feminization surgeons and consists of removal of the anterior table of the frontal sinus, thinning of the bone flap, and replacement of that bone onto the frontal sinus but in a more recessed position, in addition to a reduction of the remainder of the supraorbital ridge.[4][10] An alternative to removal and recession of the frontal sinus's anterior table is to thin the bone with a drill and then infracture it in a controlled fashion to produce the desired contour, which is also performed routinely by some authors.[11]

Other common surgical interventions requested by transgender women include feminization of the eyes via lateral canthoplasty, reduction rhinoplasty, malar implant placement or fat transfer, upper lip lift, mandibular angle reduction, genioplasty, rhytidectomy, laser hair removal, and laryngeal chondroplasty ("tracheal shave"). Because of the breadth of procedures often performed during gender affirmation of the head and neck, it is advisable to employ a multidisciplinary model for delivering patient care, in which a plastic surgeon or facial plastic surgeon may perform the brow and scalp surgery as well as the lip lift, rhinoplasty, implant or fat placement, and/or rhytidectomy; an oral surgeon may provide the mandibular angle reduction and genioplasty; an ophthalmologist or oculoplastic surgeon may perform the canthoplasty; a laryngologist or otolaryngologist may offer laryngeal chondroplasty or voice feminization surgery, and a dermatologist may provide laser and injectable treatments. Beyond the procedure-oriented physicians, however, it is critical to remember the roles of endocrinologists or primary care providers and behavioral health providers on the team because they will often provide longer-term continuity of care for transgender patients.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

There are numerous differences between male and female morphology in the head and neck region, including but not limited to:[12][13][14]

- Hairline shape (males typically have an M-shaped hairline and females have a rounded hairline)

- Hairline position (males often have a higher hairline than females, particularly as patients age)

- Eyebrow position (male eyebrows are classically located at the supraorbital rim, while female brows are often positioned higher)

- Eyebrow shape (male eyebrows are classically described as flatter than females', but this depends largely on grooming preference and fashion)

- Frontal bossing (males almost always have a more prominent supraorbital ridge than females)

- Eyelid creases (males generally have lower supratarsal creases than females, typically located 7-8 mm above the lash line in Caucasian males and 10-12 mm above in females; in non-Caucasian patients, the creases may be lower or absent in either gender)

- Zygomatic arch width (males frequently have narrower midfaces than females)

- Facial fat pads (males commonly have fuller buccal fat pads and females have more malar fat volume)

- Nasal radix depth (Caucasian males often have a deeper nasal radix than Caucasian females)

- Nasal dorsum height (males often have a higher, straighter, or convex dorsum as compared to a lower and potentially slightly scooped female nasal dorsum)

- Nasal tip rotation (male leptorrhine nasal tips are classically described as less rotated than females, with a nasolabial angle of 90-95 degrees, compared to a female angle of 100 to 115 degrees; the angle can be more obtuse in shorter women)

- Skin thickness (males tend to have thicker, oilier skin than females, which is important to consider when reducing bone volume because the surgeon must overcorrect in order to account for soft tissue depth)

- Lip thickness (males usually have thinner lips than females, although age may be a greater determinant of lip volume than gender)

- Dental show (males tend to demonstrate less maxillary dental show at rest than females; younger females, in particular, are more likely to demonstrate upper dental show in repose)

- Dental profile (male teeth, particularly incisors, have a more square shape with sharp corners, whereas female teeth tend to have a rounded contour and may be smaller overall)

- Facial hair (generally, only males have facial and cervical hair, the latter of which may blend with thoracic hair; female facial hair tends to be very limited unless advanced age or an endocrine abnormality is present)

- Mandibular angle (males often have more acute mandibular angles than females, rendering the posterior jaw more defined)

- Mandibular height (males generally have a taller mandibular ramus than females, which also contributes to the prominence of the mandibular angle)

- Mandibular width (males tend to have a wider mandible than females when measured between the angles)

- Masseter volume (male masseter muscles are often larger than females, thus making the mandible and lower face appear fuller)

- Chin width (male chins are usually wider than female chins, paralleling the greater mandibular width at the angle)

- Chin protrusion (male chins tend to project farther anteriorly than female chins)

- Laryngeal prominence (the thyroid and cricoid cartilages of the male larynx tend to be more visible than the female equivalents)

Over time, sexual dimorphism in the face fades, leading to less clear-cut differences between male and female features, which likely accounts for the adage that "old married couples start to look alike." For this reason, aging face surgery is often combined with gender affirmation surgery in older patients in order to re-establish sexual dimorphism.

Indications

In its Standards of Care 7 document, the WPATH did not promulgate specific criteria for performing facial gender affirmation surgery in transgender patients, nor did it explicitly categorize facial surgery as either medically necessary or cosmetic. That said, facial surgery is a cornerstone of gender transition, particularly in male to female transitions, in which hormone therapy makes less of a definitive difference in the face.[15]

Even though there are no particular WPATH recommendations for either duration of hormone therapy or for behavioral health evaluation, there is a role for both in establishing candidacy for facial gender affirmation surgery. Many surgeons prefer that patients, especially transgender females, undergo at least 12 months of hormone therapy before surgery to permit changes in skin thickness and hair growth to become apparent preoperatively. Likewise, evaluation for psychological suitability for surgery may be helpful to decrease the risk of postoperative depression, or even the risk of suicide, as recovery from surgery can be very stressful for patients.

For patients who have received hormone therapy of appropriate duration and are emotionally prepared for surgery, the choice of which procedures to undergo will be based on personal preference and a thorough discussion of goals and expectations with the surgeon. Each patient will have different needs, but frontal cranioplasty with brow ridge reduction and hairline advancement as well as mandibular angle reduction and genioplasty are very common interventions for the male to female transition. Lip lifting, rhinoplasty, and laryngeal chondroplasty are frequently selected as well, and many patients, particularly older transgender women, will also benefit from concomitant fat transfer, or cheek implants, and rhytidectomy.

Patients transitioning from female to male are less likely to require facial surgery because of the effects of testosterone therapy but may still benefit from augmentation of the buccal fat pads or mandible. In either case, vocal surgery may also be helpful occasionally, although speech therapy to adopt more feminine cadence and intonation may be adequate on its own. Testosterone therapy will often deepen the voice sufficiently to obviate the need for voice masculinization procedures.

Contraindications

Contraindications to facial gender affirmation surgery are similar to those that would prevent any other type of major facial surgery: cardiopulmonary disease, bleeding diatheses, malnutrition, history of poor wound healing or anesthetic complications, or other major comorbidities. Additionally, psychological instability, which could manifest as anything from a history of consistent dissatisfaction with plastic surgical outcomes to body dysmorphic disorder to suicidal ideation, should likely prevent proceeding with surgery.

Hormone therapy is a consideration as well: insufficient duration of therapy should result in a delay in order to allow the effects of the hormones to manifest themselves prior to surgery, and estrogens should ideally be held for two weeks preoperatively in order to reduce the risk of venous thromboembolism. Lastly, smoking is a relative contraindication as well. Patients who smoke are at a higher risk for wound healing problems, and when smoking is combined with estrogen therapy, the risk of venous thromboembolism is greatly increased.[16][17][18]

Equipment

Required equipment will vary depending on exactly which procedures will be performed:

Frontal Cranioplasty with Brow Lift and Hairline Adjustment

- Skin marker

- #15 blade scalpel

- Adson-Brown forceps

- Raney clips and applier

- Bipolar electrocautery

- Freer elevator

- Cottle elevator

- 1/4 curved Daniel endoscopic forehead elevator

- Stevens tenotomy scissors

- Double pronged Joseph skin hooks

- High-speed drill with 6 mm and 2 mm cutting burs, 5 mm and 4 mm diamond burs, and Endotine drill bit

- Through-cutting Janssen-Middleton forceps

- Endotine implants or similar, 3.0 or 3.5 mm x2

- Midface plating set

- 2 and 3 mm straight osteotomes

- Mallet

- Goodhill suction

- Halsey needle driver

- Suture scissors

- 3-0 polyglactin suture

- 4-0 poliglecaprone suture

- 5-0 plain gut suture

- Bacitracin ointment

Lip Lift

- Skin marker

- #6700 Beaver blade

- Westcott scissors

- Kaye blepharoplasty scissors

- 0.5 mm Castroviejo forceps

- Adson-Brown forceps

- Suture scissors

- Castroviejo needle driver

- Bipolar electrocautery

- 5-0 poliglecaprone suture

- 6-0 polypropylene suture

- Bacitracin ointment

Mandibular Angle Reduction

- Headlight

- Monopolar electrocautery

- Molt elevator

- Minnesota retractor

- Army-Navy retractor

- Cheek retractor

- Goodhill suction

- Reciprocating or oscillating saw

- Kocher clamp

- High-speed drill with pineapple bur

- Halsey needle driver

- Gerald forceps

- 3-0 polyglactin suture

- Suture scissors

Genioplasty

- Headlight

- Monopolar electrocautery

- #15 blade scalpel

- Molt #9 elevator

- Freer elevator

- Woodson elevator

- Minnesota retractor

- Army-Navy retractor

- Cheek retractor

- Goodhill suction

- Reciprocating saw

- High-speed drill

- Mandible plating set

- Halsey needle driver

- Gerald forceps

- 3-0 polyglactin suture

- Suture scissors

Laryngeal Chondroplasty

- #15 blade scalpel

- Army-Navy retractor

- Senn retractors

- Goodhill suction

- Monopolar electrocautery

- DeBakey forceps

- Freer elevator

- Petit-point Crile forceps

- High-speed drill with pineapple bur

- Halsey needle driver

- Adson-Brown forceps

- Suture scissors

- 3-0 silk suture

- 3-0 polyglactin suture

- 4-0 poliglecaprone suture

- 5-0 polypropylene suture

- Bacitracin ointment

For the equipment requirements of additional procedures, such as rhinoplasty, autologous fat transfer, and face lifting, please see the relevant StatPearls articles.[19][20][21]

Personnel

To maximize the surgical result, the following personnel should contribute to the healthcare team:

- Surgeon (plastic surgeon, facial plastic surgeon, oculoplastic surgeon, and/or an oral surgeon)

- Surgical first assist (second attending surgeon, surgical trainee, physician assistant, or RN first assist)

- Anesthesia provider

- Circulating nurse

- Surgical technologist

- Endocrinologist

- Behavioral health provider (psychiatrist, psychologist, or other counselors)

Preparation

Preparation for surgery centers around determining the patient's goals, what changes the patient's anatomy will support, and having a candid discussion about what to expect in the perioperative period. In addition to taking a thorough history to determine the patient's candidacy for surgery and minimize the risk of a general anesthetic, it is important to pay particular attention to the patient's clotting risk. Most patients requiring facial surgery for gender affirmation will be undergoing facial feminization, which is usually performed in patients receiving estrogen therapy; estrogens increase the risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.[22]

In many regions, gender affirmation surgery is often unavailable outside of urban areas with academic medical centers. Patients may need to travel relatively long distances to receive care, further compounding the risk of thromboembolic events in the perioperative period. For this reason, many surgeons recommend that patients pause hormone therapy for two weeks prior to surgery. Preoperative hormonal therapy is critical for both transgender men and women; however, in the case of transgender men, testosterone administration for one to two years may obviate the need for facial surgery due to the development of secondary sex characteristics it produces.

Imaging is also frequently obtained to aid preoperative planning, both photographic and radiographic. Standard photography similar to that employed for patients undergoing aging face surgery and rhinoplasty is recommended, ideally performed with a digital single-lens reflex camera in a dedicated photography lab with dual flashes and the patient positioned in the Frankfort horizontal plane. Multiple views are necessary from different angles and at different magnifications to inform preoperative planning and provide the surgeon reference images intraoperatively as well as comparison images postoperatively.

Computed tomography (CT) scanning can also be beneficial for planning osteotomies, as it can determine the thickness of the frontal bone and inform the selection of cranioplasty technique and facilitate identification of the borders of the frontal sinus. Additionally, CT scans can be used to plan the reduction of the mandibular angles and the chin to avoid injury to the inferior alveolar nerve, particularly when three-dimensional reformatting of the images is performed. Those same reformatted images can be used for preoperative surgical simulation, which may be combined with 3D printing technology to produce cutting guides that potentially improve the symmetry and consistency of surgical outcomes.

Technique or Treatment

Frontal Cranioplasty with Brow Lift and Hairline Adjustment

The most commonly described approach to frontal cranioplasty is via a pretrichial incision. This provides excellent exposure of the frontal calvarium and supraorbital region, but it also facilitates adjustment of the frontal hairline without an additional incision.[7][10][23][24]

A pretrichial incision will start at the root of the helix and travel superiorly within the temporal hair tuft until reaching the bald temporal skin characteristic of the male hairline; from that point, the incision will run just anterior to the hairline across the forehead to the other side, where it will dive back into the temporal hair tuft and end at the contralateral helical root. For patients whose hairline does not require adjustment, consideration should be given to a more traditional coronal incision, which has the advantage of avoiding a scar at the frontal hairline but may cause a visible scar if the patient wears her hair short. However, many transgender women prefer to wear wigs, making a coronal incision a viable option in those cases.

Once the incision is made, Raney clips may be applied to prevent bleeding from the skin edges. A flap is then developed in the central forehead, following a subperiosteal plane down to the supraorbital ridge level. Laterally, the flap must be elevated deep to the temporoparietal fascia (superficial temporal fascia) to avoid injury to the facial nerve's frontal branch and subsequent brow paralysis. These authors prefer to dissect the temporoparietal fascia and the fascia of the temporalis muscle (deep temporal fascia). Still, some surgeons dissect deep to the deep temporal fascia, which can be bloodier but leaves one more fascial layer between the dissection and the nerve. The nerve runs deep within the temporoparietal fascia (TPF) or on its deep surface; its course is approximated by a line drawn between a point 0.5 cm inferior to the tragus and a point 1.5 cm superior to the lateral brow (Pitanguy's line); the frontal branch of the facial nerve is one of the most commonly injured nerves during aging face surgery.[25][26]

The central and lateral dissection compartments are separated by the conjoint tendons, which must be divided to release the forehead flap and permit the brow ridge's exposure. The conjoint tendons are fascial condensations that occur along the temporalis muscle border; the TPF, deep temporal fascia, galea aponeurosis, and pericranium all meet together at the conjoint tendons and adhere to the skull. It is important to elevate the periosteum all the way from lateral canthus to lateral canthus and then to divide and spread the arcus marginalis in the same location to release the brows sufficiently to perform an effective brow lift. The arcus marginalis is a fascial condensation of pericranium, periorbita, and orbital septum that occurs around the orbital rim. Exposure of the supraorbital rims should include identifying and preserving the supraorbital neurovascular bundles; however, the supratrochlear bundles are not necessarily identified in every case. Approximately 25% of the time, the supraorbital nerve will exit the skull through a foramen; in those cases, removing the bone from the inferior aspect of the foramen with a 3 mm straight osteotome will release the bundle and permit reflection of the flap inferiorly enough to expose the bone of brow.

After complete exposure of the supraorbital ridge, frontal cranioplasty may begin. Some surgeons start by burring down bone from the region of the zygomaticofrontal suture and moving medially toward the lateral border of the frontal sinus; others prefer to begin identifying the frontal sinus borders, assuming that the frontal sinus is pneumatized based on the preoperative CT scan. There are numerous ways to determine the extent of the frontal sinus; the traditional method involves printing a plain film Caldwell view X-ray taken from six feet away from the patient and bringing it to the operating room for sterilization and use as a template. In the United States, it is becoming increasingly difficult to print X-rays from a logistical standpoint, as most radiographs are now viewed on computer monitors. Transillumination of the sinus is another option, using a sinus endoscope applied to the superomedial orbit.

If the intersinus septa are not thick and the sinus is not large, the light may travel through the whole frontal sinus and define its boundaries. This method does not provide acceptable results in all patients if the intersinus septa are thick or numerous or if the frontal sinus is large. If the patient has had a prior frontal sinusotomy, placement of an endoscope in the middle meatus of the nasal cavity may provide enough light to transilluminate the entire frontal sinus endoscope will not usually pass into this location in the absence of prior surgery. However, a lighted fiberoptic wand can be passed intranasally through the frontal sinus outflow tract in unoperated patients and used to transilluminate the frontal sinus effectively and reliably, although the placement of the fiber can be challenging in some cases.

Another method that takes even less time in the operating room is using a 3D-printed cutting guide based on the preoperative CT scan. Still, while this may be the fastest method of identifying the frontal sinus, it can also be expensive. Higher volume surgeons may forgo all of the above methods of locating the frontal sinus and instead, elect to identify its borders directly by burring down bone from lateral to medial until encountering the point at which the bone becomes thin and translucent enough to visualize the dark blue color of the frontal sinus submucosa ("blue-lining" the sinus). Once the frontal sinus borders are defined, the anterior table can be removed using a combination of a 2 mm cutting bur on a high-speed drill and 2 and 3 mm osteotomes. The bone flap is then thinned on the back table in preparation for replacement in a recessed position. Recessing the anterior table requires removing the intersinus septum, which can be accomplished with a drill or a rongeur, such as Janssen-Middleton forceps. The bone flap is then replaced in its new position and fixated using low profile titanium mini plates (0.6 mm) and short screws (4 to 5 mm).

In the rare cases that the frontal sinus is absent or the bone of the anterior table is exceptionally thick, simple burring of the bone may produce the desired contour (type 1 frontal cranioplasty) and obviate the need for removal and recession of the anterior table (type 3 frontal cranioplasty). Instead of a formal type 3 cranioplasty, some surgeons prefer to bur the bone of the anterior table down until it is extremely thin and then fracture it gently with a mallet to achieve the desired contour; this technique may be more effective when the intersinus septum is absent or very thin because the septa limit the extent to which the anterior table bone can be recessed.

Once the frontal sinus has been addressed, the remainder of the supraorbital ridge can be reduced with a high-speed drill and 6 mm cutting bur, with a 5 mm diamond bur used to smooth the bone after the reduction. Some surgeons also elect to open the orbits slightly by burring the undersurface of the supraorbital rims, which can feminize the eyes but should be performed judiciously. It can also contribute to the hollowing of the orbits by increasing the intraorbital volume. Ideally, after the frontal cranioplasty is complete, the bony brow will have been reduced beyond the contour of a biologically female skull to provide a measure of overcorrection.

Overcorrection is important because biologically, male brow and forehead skin is thick and sebaceous and will somewhat decrease the visual effect of the bony reduction; furthermore, over feminization of the features being addressed surgically is desirable because it helps to compensate for the masculine appearance of features that cannot be changed surgically, such as the width of the shoulders and the shape of the hands, providing an overall appearance consistent with female gender despite features that remain characteristically masculine.

Upon conclusion of the frontal cranioplasty, the brow lift is performed in conjunction with the closure of the incision. Because of the reduction of supraorbital bone and the release of the arcus marginalis, the brow will often elevate without much additional effort. Nevertheless, some surgeons prefer to place resorbable forehead implants to aid with fixation of the forehead flap in an elevated position during the healing process. If used, implants are placed superior to the peak of the brow, which is usually located between the medial limbus of the iris and the lateral canthus. The farther inferiorly the implants are placed, the more effective the lift will be. Still, the more visible the implants may appear beneath the skin until they dissolve, several months after placement.

An alternative to the forehead implants usually used for an endoscopic brow lift is the transblepharoplasty implant, which is a lower profile device that is less noticeable when placed just superior to the hair-bearing brow. In either case, the implants are secured into the frontal calvarium by drilling wells using device-specific bits and snapping the implants in place with the barbs pointing superoposteriorly. The forehead flap is then redraped and pulled superiorly before pressing the skin down over the Endotines to engage the periosteum on the barbs of the devices. Excess skin at the incision is then trimmed prior to closure, generally with removing the widow's peak centrally and bald scalp temporally. Removal of a portion of temporal hair tuft from the flap may also help to provide a lateral lift to the brow, which older patients can greatly appreciate.

If significant advancement of the hair-bearing scalp is required, placement of additional implants oriented 180 degrees opposite the pair used for the brow lift can help prevent the hairline from retracting posteriorly. Skin closure should be accomplished in layers, with reapproximation of the galea, subdermal, and skin surface performed separately. A closed suction drain is unlikely to be helpful because it will usually pull air through the nose and frontal sinus into the potential space under the flap rather than evacuating much fluid. Still, a pressure dressing, such as a Barton dressing, may be applied for 24 hours to alleviate swelling that may occur.

Rhinoplasty

Rhinoplasty can be an essential part of facial feminization for many patients because of the numerous differences between male and female noses.[27] While an in-depth description of rhinoplasty techniques is beyond this article's scope, it is worth mentioning that many of the techniques employed in gender affirmation surgery are also used for cosmetic reduction rhinoplasty. Specific examples include dorsal hump reduction, upward rotation and deprojection of the tip, cephalic trimming of the lower lateral cartilages' lateral crura, and dome divisions.[28]

When performing aggressive reduction rhinoplasty, it is important to consider the nasal airway implications of the procedure and to take the opportunity to improve airflow through the use of techniques such as inferior turbinoplasty, septoplasty, and internal nasal valve support so that reducing the size of the nasal skeleton does not result in nasal airway obstruction. Placement of thin spreader grafts or upper lateral cartilage turn-in flaps (auto spreader flaps) can significantly impact nasal airflow without necessarily widening the middle third of the nose noticeably.[29][30][31][32]

Many of the techniques described in other StatPearls articles on rhinoplasty are applicable as well, and it is also worth mentioning that open rhinoplasty can be approached safely via the bullhorn incision used for lip lifting to spare the patient an additional inverted-V transcolumellar scar.[33][19][34][33]

Lip lift

Lip lifting is a procedure that is frequently performed as a cosmetic intervention in cisgender women to shorten the cutaneous upper lip, which often elongates with age, and to evert and enlarge the vermilion upper lip while increasing resting maxillary dental show. All of these effects increase the femininity of the upper perioral region, making this procedure a beneficial adjunct for facial feminization. A common approach to the lip lift employs a "bullhorn" subnasal incision, which extends around the lateral aspect of the nasal ala, proceeds under the columella, and continues to the contralateral ala.[35]

The incision is designed to hide the final scar in the boundary between the nasal and upper lip facial subunits. The marked excision height will depend on the degree of cutaneous lip shortening, and upper lip eversion desired but will usually include 1/4 to 1/3 of the height of the cutaneous upper lip. If possible, the lip lift should be performed before any mandibular procedures, as these tend to produce a significant amount of edema that makes judging where to place the bullhorn incision challenging.

The incision should be made very carefully, using a fine scalpel, such as a #15C or a #6700 Beaver blade. Once the incision is complete, the skin should be completely excised using sharp scissors; no dermis should remain. However, there will be a fine layer of fat covering the just visible orbicularis oris muscle. Hemostasis is achieved with the conservative application of bipolar electrocautery. Skin closure is performed in layers with several carefully placed deep dermal sutures of 5-0 poliglecaprone or polydioxanone, taking care to align the philtrum columns properly and avoid step-offs. The skin surface is closed with interrupted 6-0 polypropylene or nylon, and antibiotic ointment is applied. Patients should be advised to avoid sun exposure to the area for a full year after surgery to prevent the scar from developing hyperpigmentation. Postoperative laser treatment may help to minimize the appearance of the scar.

Mandibular Angle Reduction

Reduction of mandibular width can be very important for feminizing the lower third of the face, and many transgender women will benefit from mandibular angle reduction. In some cases, preoperative botulinum toxin administration can cause enough decrease in masseter muscle volume that surgical intervention on the mandible is no longer necessary. Still, many patients prefer the more dramatic and durable long-term results achieved with surgery. Chemodenervation can nevertheless be a useful postoperative adjunct as well.

Mandibular angle reduction surgery is a technically challenging procedure due to access constraints and the need for symmetric osteotomies between the left and right sides. Approaching the mandibular angles via an extraoral approach will place a scar on the neck and risks facial nerve injury. In contrast, the intraoral approach severely limits visualization of the area in question and makes achieving a symmetric result difficult. When an extraoral approach is selected, it often accompanies a face or neck lift because the area is already exposed via a Blair incision. From this approach, the superficial musculoaponeurotic system must be incised to expose the masseter muscle, which envelops the angle of the mandible. Care is necessary during this portion of the procedure because the facial nerve's marginal mandibular and cervical branches often overlie the mandible in this area. In the region of the mandibular angle, posterior to the gonial notch, the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve lies superior to the inferior border of the mandible in 80% of patients and inferior to it in 20%; anterior to the gonial notch, where the facial artery crosses the mandible, the marginal mandibular branch is consistently superior to the inferior border of the mandible.[36][37]

The cervical branch of the facial nerve lies inferior to the marginal mandibular branch. It is consistently found 1 cm below the halfway point of a line drawn between the mentum and the mastoid tip, although proximally in its course, it may share a common root with the marginal mandibular branch.[38] A nerve stimulator will help identify motor nerve branches and may prevent iatrogenic injuries, provided the patient has not received paralytic drugs. Once the masseter has been exposed safely, it can be incised along the posterior border of the mandibular angle and elevated off the bone. A reciprocating saw is then used to perform the osteotomy. The medial pterygoid muscle is elevated from the medial surface of the bone fragment to liberate it completely.

If an intraoral approach is preferred, an incision is made with monopolar electrocautery along the mandible's external oblique ridge, running from the first molar posterosuperior to the level of the occlusal plane. Care is necessary to leave an adequate cuff of tissue on the gingiva (approximately 3 mm) to facilitate passing sutures for closure. A mucoperiosteal flap is raised, and the temporalis tendon and masseter are elevated off the ramus to expose the mandibular angle; good retraction and illumination are critical. The use of a rigid 30-degree endoscope may facilitate visualization during this portion of the procedure.

Once the angle is exposed, a 90 degree 7 mm oscillating saw is used to make the osteotomy through both cortices of the mandible, taking care to avoid injury to the inferior alveolar nerve, whose position would have been determined by the preoperative CT scan. After the osteotomy is complete, the mandibular bone fragment must be stabilized, such as with a Kocher clamp. At the same time, the pterygoid musculature is stripped away from its medial aspect to permit the removal of the bone. Any sharp bony edges should be smoothed with a pineapple bur on a high-speed drill. Hemostasis is achieved with electrocautery before the closure of the incision in a single layer with a 3-0 gut or polyglactin suture.[39] As with the frontal cranioplasty, the use of 3D-printed cutting guides for mandibular angle reduction can help improve symmetry and avoid complications.

Genioplasty

Reduction of chin width and protrusion can significantly improve the femininity of the lower third of the face.[40] As with mandibular angle reduction, genioplasty can be performed via either intraoral or extraoral incisions. The advantage to the intraoral incision is that it avoids an external scar, but it does place the mental nerves at a higher risk than a submental incision would. The mental nerves exit the anterior mandible through foramina inferior to and between the first and second bicuspids, which generally falls on the mid pupillary line, below the supraorbital and infraorbital notches, and foramina.

The mental nerves rapidly arborize upon exiting the mandible and provide sensation to the chin and lower lip. The intraoral incision for genioplasty is performed using monopolar electrocautery transversely between the mandibular canines, incising down to the bone and permitting a mucoperiosteal's development flap down to the inferior border of the mandible, which includes elevating the mentalis muscle from the bone. Again, leaving a 3 mm cuff of gingiva is critical for facilitating closure.

The mental nerves are typically identified at this stage for their protection during the remainder of the procedure. Using electrocautery or a reciprocating saw, the midline of the mandible should be marked from the level of the incision down to the inferior margin to ensure that the osteotomized segment can be realigned properly at the conclusion of the procedure. The saw is then used to make a transverse osteotomy through the anterior mandible, taking care to remain inferior to the course of the inferior alveolar nerves, which may dip below the level of the mental foramina; as with mandibular angle reduction, preoperative CT imaging will allow the surgeon to plan safe osteotomies.

If the chin is to be narrowed, a central segment can be removed from the osteotomized bone, and the two lateral halves fixated together to decrease the overall width. If both the height and the protrusion are to be reduced, the transverse osteotomy may be made obliquely such that the cut runs from anteroinferior to superoposterior to permit the fragment to slide superiorly as it recesses posteriorly. Simply moving the bone fragment posteriorly, roughly 3 to 4 mm, will suffice in many cases. After the osteotomy is complete, the bone fragment or fragments are fixated with a titanium step-off plate and monocortical screws, taking care to maintain the mandibular midline's alignment. Skin closure is accomplished in a single layer with 3-0 gut or polyglactin suture. A foam tape dressing is applied to ensure the mentalis muscle re-adheres to the mandible to prevent the chin's soft tissue ptosis.

The extraoral approach to genioplasty is similar to the intraoral but is performed via a submental incision. This approach exposes the anterior mandible from its inferior aspect, which can be disorienting without a concomitant view of the teeth. The mental nerves represent the superior border of dissection, but the remainder of the procedure is nearly identical. To ensure precise osteotomies and accurate reduction of chin height, width, and/or protrusion, 3D-printed cutting guides can help. When cutting guides are produced for frontal cranioplasty, mandibular angle reduction, and genioplasty for the same patient, the cost per guide is reduced because only one CT scan is required. Although the extraoral approach does leave an external scar, this incision may also be useful for approaching the thyroid cartilage when performing a laryngeal chondroplasty to reduce the appearance of a prominent Adam's apple.

Laryngeal Chondroplasty

Reduction of the thyroid cartilage to feminize the neck can be accomplished via several different approaches, including a direct incision immediately overlying a prominent Adam's apple, a higher neck incision positioned at the cervicomental angle, a submental incision, and even an intraoral gingivolabial incision - the latter two approaches are also used to perform genioplasty. Once the incision is made, a subplatysmal flap must be developed down to the level of the cricoid cartilage to provide enough exposure for the procedure.

The elasticity of neck skin and the chin's comparative proximity to the larynx make exposure of the thyroid cartilage through incisions that may seem distant better than one might expect. With the platysma elevated, the sternohyoid muscles are identified and separated in the midline. Incision of the perichondrium of the thyroid cartilage will permit elevation of a subperichondrial flap and mobilization of the attachments of the thyrohyoid and sternothyroid muscles. If the incision is close to the thyroid cartilage, the muscles may be retracted directly with Senn rakes, or if the incision is farther away, transcutaneous 3-0 silk retraction sutures may be passed through the skin and muscles for exposure of the underlying cartilage.

Once the thyroid cartilage is exposed from notch to cricothyroid membrane and the periosteum elevated, a #15 blade is used to resect the prominence portion. In older patients, the cartilage may be calcified and challenging to incise with a scalpel; in this case, a pineapple bur on a high-speed drill may be required. It is essential to avoid inadvertently entering the airway by violating the perichondrium and mucosa on the deep surface of the thyroid cartilage, and even more critical to limit resection to the upper 1/2 of the cartilage to avoid either destabilizing the larynx or injuring the anterior commissure of the vocal folds, which is located approximately one-third of the way up from the inferior border of the thyroid cartilage in adults and halfway up in children. If the thyroid alae appear mobile after reduction, placement of a 5-0 polydioxanone suture may improve stability; closure is then accomplished in layers, reapproximating the strap muscles first with interrupted 3-0 polyglactin suture, followed by 4-0 buried, interrupted poliglecaprone in the platysma and running 5-0 polypropylene or nylon in the skin.[41]

Postoperative Care

Patients should r4eceive adequate pain control, antiemetics, and stool softeners; antibiotics may also be helpful, particularly since implants are often used. The pressure dressing should be removed 24 hours after surgery, and any nasal casts or splints should be removed after one week. Non-dissolving sutures should also be removed at one week when the patient returns for a wound check. It is important that the patient not perform any strenuous exercise or heavy lifting for at least two weeks postoperatively. Nose blowing and bending over should also be discouraged. If mandibular angle reduction or genioplasty is performed, a soft diet may be more comfortable initially. At night, patients should sleep with the head of the bed elevated to 30 degrees, either with pillows behind the back and head or by sleeping in a recliner. If blepharoplasty or rhytidectomy is performed, the application of ice packs will help to limit edema and ecchymosis.

Complications

The most common adverse outcome of facial gender affirmation surgery is dissatisfaction with the result, which may be due to several causes, including but not limited to: technical error, unsightly scarring, infection, alopecia, resorption of bone, and unrealistic expectations. Because these operations are frequently long in duration due to the number of procedures required under the same anesthetic, the risk of postoperative thromboembolic events is substantial. The healthcare team must be vigilant for signs of deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Additionally, each procedure possesses particular risks beyond those already mentioned.

Frontal cranioplasty carries the risk of forehead hypesthesia, brow weakness, nasofrontal duct obstruction, hematoma, and cerebrospinal fluid leak due to violation of the posterior table of the frontal sinus.[42] Rhinoplasty, particularly reductive rhinoplasty, may result in nasal obstruction or septal perforation.

The most common complication of lip lifting is an unsightly scar, although this is rare if care is taken with closure and sunlight is avoided postoperatively. Genioplasty can be complicated by hypesthesia of the chin and lower lip and soft tissue ptosis, or "witch's chin" if the mentalis muscle is not resuspended appropriately. Mandibular angle reduction may result in inadvertent fractures or injury to the inferior alveolar nerve, which will also result in numbness of the lower lip and chin, as well as the ipsilateral mandibular dentition.

Reduction of the thyroid cartilage, if overaggressive, may cause damage to the anterior commissure of the vocal folds, with ensuing speech and swallowing difficulties. Lastly, if additional aging face procedures are performed concomitantly, brow malposition, fat resorption, skin sloughing, great auricular nerve injury, facial nerve injury, pixie ear deformity, and cobra neck deformity are all potential adverse outcomes as well.

Clinical Significance

Transgender patients are at high risk for behavioral health conditions, with 39% of respondents to the USTS having reported serious psychological distress within the month before completing the survey, and 40% demonstrated an attempted suicide at some point in the past. Verbal (46%), physical (9%), and sexual assault (47%) are extremely common.

Discrimination occurs in many different domains as well, such as wrongful termination/denial of promotion (30%), eviction or denial of lease/mortgage (23%), lack of family support (18%), rejection by their religious communities (19%), and mistreatment by law enforcement (58%), with transgender individuals of color being even more likely to suffer discrimination.

While some third-party payers consider facial surgery for gender transition to be elective at best or cosmetic at worst, these operations have the potential to be hugely beneficial to patients, and many surgeons consider them to be medically necessary for this reason. In fact, facial features are the most important external determinants of gender, in that transgender women who have undergone facial surgery are more likely to be identified consistently as female by bystanders, and as a result, are less likely to be singled out or victimized as gender non-conforming individuals, thus making them safer from physical and emotional harm.[43]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Transgender patients have not only multiple different needs from a surgical perspective but also require medical management and behavioral health care in the vast majority of cases. Because of the number of different medical and surgical specialties involved in the management of gender dysphoria, as well as non-physician team members such as speech therapists, nurses, and psychologists, it is important to have a cohesive multidisciplinary team.[44][45]

Patients may also benefit from well-defined institutional pathways that begin with primary care, proceed to behavioral health, then endocrinology, and after an appropriate period of time, surgical specialists as necessary. Institutions can further improve the environment of inclusion by asking patients to provide their preferred pronouns and gender identity and by ensuring clinical staff members do the same because misgendering can be a major source of stress and dissatisfaction for transgender patients.

Many university health centers have also started providing non-gender-specific restrooms, which contributes to putting individuals who identify as gender non-binary at ease within the building. For many healthcare providers, the care of transgender patients is a new and unanticipated opportunity to broaden their horizons, and it is important to actively seek ways to be more inclusive in speech and action and to help colleagues to do the same in order to avoid further marginalizing a demographic group that has historically suffered a great deal of discrimination and difficulty accessing healthcare. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Differences between male and female skulls. The red arrow indicates frontal bossing, which is consistently more apparent in male skulls; the nasal radix (green arrow) is consequently deeper in the male skull. The yellow arrow demonstrates greater prominence of the chin in the male skull, and the blue arrows show a greater mandibular height in the male as well. In this example, the male skull has a more obtuse mandibular angle (purple arrow) than the female skull, which is atypical, illustrating the important point that not all of the listed sexually dimorphic traits are found in all patients. Contributed by Marc H Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Iatrogenic vertical fracture of the mandibular ramus, extending through the sigmoid notch, that occurred during reduction of the mandibular angles during facial feminization. Note the plates in place fixating osteotomies for the frontal cranioplasty and genioplasty. Contributed by Marc H Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

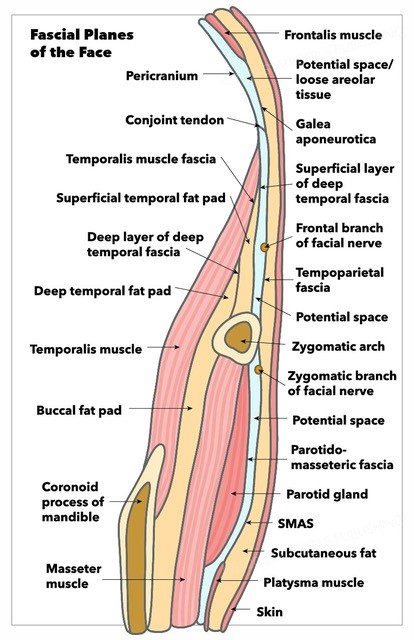

Fascial Planes of the Face and Musculature. This illustration depicts the fascial planes of the face, highlighting the continuity of the frontalis muscle, galea aponeurotica, temporoparietal fascia, superficial musculoaponeurotic system, platysma, and the location of the facial nerve.

Contributed by K Humphreys and MH Hohman, MD, FACS

References

Meerwijk EL, Sevelius JM. Transgender Population Size in the United States: a Meta-Regression of Population-Based Probability Samples. American journal of public health. 2017 Feb:107(2):e1-e8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303578. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28075632]

Unger CA. Hormone therapy for transgender patients. Translational andrology and urology. 2016 Dec:5(6):877-884. doi: 10.21037/tau.2016.09.04. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28078219]

Ascha M, Swanson MA, Massie JP, Evans MW, Chambers C, Ginsberg BA, Gatherwright J, Satterwhite T, Morrison SD, Gougoutas AJ. Nonsurgical Management of Facial Masculinization and Feminization. Aesthetic surgery journal. 2019 Apr 8:39(5):NP123-NP137. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjy253. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30383180]

Spiegel JH. Facial determinants of female gender and feminizing forehead cranioplasty. The Laryngoscope. 2011 Feb:121(2):250-61. doi: 10.1002/lary.21187. Epub 2010 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 21271570]

Sadr J, Jarudi I, Sinha P. The role of eyebrows in face recognition. Perception. 2003:32(3):285-93 [PubMed PMID: 12729380]

Capitán L, Simon D, Bailón C, Bellinga RJ, Gutiérrez-Santamaría J, Tenório T, Capitán-Cañadas F. The Upper Third in Facial Gender Confirmation Surgery: Forehead and Hairline. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2019 Jul:30(5):1393-1398. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000005640. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31299729]

Garcia-Rodriguez L, Thain LM, Spiegel JH. Scalp advancement for transgender women: Closing the gap. The Laryngoscope. 2020 Jun:130(6):1431-1435. doi: 10.1002/lary.28370. Epub 2019 Dec 4 [PubMed PMID: 31800096]

Capitán L, Simon D, Meyer T, Alcaide A, Wells A, Bailón C, Bellinga RJ, Tenório T, Capitán-Cañadas F. Facial Feminization Surgery: Simultaneous Hair Transplant during Forehead Reconstruction. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2017 Mar:139(3):573-584. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000003149. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28234823]

Ousterhout DK. Feminization of the forehead: contour changing to improve female aesthetics. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1987 May:79(5):701-13 [PubMed PMID: 3575517]

Capitán L, Simon D, Kaye K, Tenorio T. Facial feminization surgery: the forehead. Surgical techniques and analysis of results. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2014 Oct:134(4):609-619. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000545. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24945951]

Villepelet A, Jafari A, Baujat B. Fronto-orbital feminization technique. A surgical strategy using fronto-orbital burring with or without eggshell technique to optimize the risk/benefit ratio. European annals of otorhinolaryngology, head and neck diseases. 2018 Oct:135(5):353-356. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2018.04.007. Epub 2018 May 4 [PubMed PMID: 29735285]

Brown E, Perrett DI. What gives a face its gender? Perception. 1993:22(7):829-40 [PubMed PMID: 8115240]

Hage JJ, Becking AG, de Graaf FH, Tuinzing DB. Gender-confirming facial surgery: considerations on the masculinity and femininity of faces. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1997 Jun:99(7):1799-807 [PubMed PMID: 9180702]

Nusbaum BP, Fuentefria S. Naturally occurring female hairline patterns. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2009 Jun:35(6):907-13. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01154.x. Epub 2009 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 19397668]

Morrison SD, Vyas KS, Motakef S, Gast KM, Chung MT, Rashidi V, Satterwhite T, Kuzon W, Cederna PS. Facial Feminization: Systematic Review of the Literature. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2016 Jun:137(6):1759-1770. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002171. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27219232]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHwang K, Son JS, Ryu WK. Smoking and Flap Survival. Plastic surgery (Oakville, Ont.). 2018 Nov:26(4):280-285. doi: 10.1177/2292550317749509. Epub 2018 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 30450347]

Goldminz D, Bennett RG. Cigarette smoking and flap and full-thickness graft necrosis. Archives of dermatology. 1991 Jul:127(7):1012-5 [PubMed PMID: 2064398]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBlondon M, Wiggins KL, Van Hylckama Vlieg A, McKnight B, Psaty BM, Rice KM, Heckbert SR, Smith NL. Smoking, postmenopausal hormone therapy and the risk of venous thrombosis: a population-based, case-control study. British journal of haematology. 2013 Nov:163(3):418-20. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12508. Epub 2013 Aug 8 [PubMed PMID: 23927442]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFichman M, Piedra Buena IT. Rhinoplasty. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32644396]

Vasavada A, Raggio BS. Autologous Fat Grafting for Facial Rejuvenation. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32491783]

Yang AJ, Hohman MH. Rhytidectomy. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 33232008]

Goldstein Z, Khan M, Reisman T, Safer JD. Managing the risk of venous thromboembolism in transgender adults undergoing hormone therapy. Journal of blood medicine. 2019:10():209-216. doi: 10.2147/JBM.S166780. Epub 2019 Jul 10 [PubMed PMID: 31372078]

Spiegel JH. Facial Feminization for the Transgender Patient. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2019 Jul:30(5):1399-1402. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000005645. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31299730]

Ousterhout DK. Facial Feminization Surgery: The Forehead. Surgical Techniques and Analysis of Results. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2015 Oct:136(4):560e-561e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001425. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25938955]

Pitanguy I, Ramos AS. The frontal branch of the facial nerve: the importance of its variations in face lifting. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1966 Oct:38(4):352-6 [PubMed PMID: 5926990]

Hohman MH, Bhama PK, Hadlock TA. Epidemiology of iatrogenic facial nerve injury: a decade of experience. The Laryngoscope. 2014 Jan:124(1):260-5. doi: 10.1002/lary.24117. Epub 2013 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 23606475]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSpiegel JH. Rhinoplasty as a Significant Component of Facial Feminization and Beautification. JAMA facial plastic surgery. 2017 May 1:19(3):181-182. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2016.1817. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27978546]

Davis AM,Simons RL,Rhee JS, Evaluation of the Goldman tip procedure in modern-day rhinoplasty. Archives of facial plastic surgery. 2004 Sep-Oct; [PubMed PMID: 15381575]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSheen JH. Spreader graft: a method of reconstructing the roof of the middle nasal vault following rhinoplasty. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1984 Feb:73(2):230-9 [PubMed PMID: 6695022]

Standlee AG, Hohman MH. Evaluating the Effect of Spreader Grafting on Nasal Obstruction Using the NOSE Scale. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2017 Mar:126(3):219-223. doi: 10.1177/0003489416685320. Epub 2017 Jan 5 [PubMed PMID: 28056521]

Byrd HS, Meade RA, Gonyon DL Jr. Using the autospreader flap in primary rhinoplasty. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2007 May:119(6):1897-1902. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000259196.02216.a5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 17440372]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHohman MH, Vincent AG, Anderson SR, Ducic Y, Cochran S. Avoiding Complications in Functional and Aesthetic Rhinoplasty. Seminars in plastic surgery. 2020 Nov:34(4):260-264. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1721762. Epub 2020 Dec 24 [PubMed PMID: 33380911]

Insalaco L, Spiegel JH. Safety of Simultaneous Lip-Lift and Open Rhinoplasty. JAMA facial plastic surgery. 2017 Mar 1:19(2):160-161. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2016.1396. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27832262]

Raggio BS, Asaria J. Open Rhinoplasty. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31536235]

Spiegel JH. The Modified Bullhorn Approach for the Lip-lift. JAMA facial plastic surgery. 2019 Jan 1:21(1):69-70. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2018.0847. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30326516]

Hazani R, Chowdhry S, Mowlavi A, Wilhelmi BJ. Bony anatomic landmarks to avoid injury to the marginal mandibular nerve. Aesthetic surgery journal. 2011 Mar:31(3):286-9. doi: 10.1177/1090820X11398352. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21385737]

Batra AP, Mahajan A, Gupta K. Marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve: An anatomical study. Indian journal of plastic surgery : official publication of the Association of Plastic Surgeons of India. 2010 Jan:43(1):60-4. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.63968. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20924452]

Chowdhry S, Yoder EM, Cooperman RD, Yoder VR, Wilhelmi BJ. Locating the cervical motor branch of the facial nerve: anatomy and clinical application. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2010 Sep:126(3):875-879. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181e3b374. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20463628]

Morrison SD, Satterwhite T. Lower Jaw Recontouring in Facial Gender-Affirming Surgery. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2019 May:27(2):233-242. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2019.01.001. Epub 2019 Mar 2 [PubMed PMID: 30940389]

Deschamps-Braly J. Feminization of the Chin: Genioplasty Using Osteotomies. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2019 May:27(2):243-250. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2019.01.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30940390]

Sturm A, Chaiet SR. Chondrolaryngoplasty-Thyroid Cartilage Reduction. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2019 May:27(2):267-272. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2019.01.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30940393]

Altman K. Forehead reduction and orbital contouring in facial feminisation surgery for transgender females. The British journal of oral & maxillofacial surgery. 2018 Apr:56(3):192-197. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2018.01.009. Epub 2018 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 29428374]

Dinno A. Homicide Rates of Transgender Individuals in the United States: 2010-2014. American journal of public health. 2017 Sep:107(9):1441-1447. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303878. Epub 2017 Jul 20 [PubMed PMID: 28727530]

Karasic DH, Fraser L. Multidisciplinary Care and the Standards of Care for Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Individuals. Clinics in plastic surgery. 2018 Jul:45(3):295-299. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2018.03.016. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29908615]

Chen D, Hidalgo MA, Leibowitz S, Leininger J, Simons L, Finlayson C, Garofalo R. Multidisciplinary Care for Gender-Diverse Youth: A Narrative Review and Unique Model of Gender-Affirming Care. Transgender health. 2016:1(1):117-123. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2016.0009. Epub 2016 Jul 1 [PubMed PMID: 28861529]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence