Introduction

Koppel and Thompson first described anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome (ATTS) in 1960.[1] ATTS, also known as deep peroneal nerve (DPN) entrapment, is a compression neuropathy of the DPN most commonly caused by the tight fascia band in the anterior ankle called the inferior extensor retinaculum. Two other anatomic locations of entrapment have been described and include deep to the extensor hallucis longus tendon overlying the talonavicular joint and deep to the extensor hallucis brevis muscle overlying the first and second tarsometatarsal joints.

The deep peroneal nerve is one of two terminal branches off the common peroneal nerve (CPN). The DPN bifurcates from the CPN in the anterior compartment of the lower leg and travels along the interosseous membrane. Just proximal to the ankle joint, the DPN courses between the extensor hallucis longus tendon and the extensor digitorum longus tendon. It then divides into the medial and lateral terminal branches. The EDB and EHB muscles are innervated by the lateral terminal branch of the DPN while the medial branch runs beside the dorsalis pedis artery in the dorsal foot and is purely sensory providing innervation to the first webspace. In the anterior leg, the DPN provides motor innervation to the tibialis anterior (TA), extensor digitorum longus (EDL), peroneus tertius, and extensor hallucis longus (EHL) muscles.

The anterior tarsal tunnel is a fibro-osseous tunnel along the anterior ankle in which the borders include the inferior extensor retinaculum (superficially/roof), medial malleolus (medially), lateral malleolus (laterally), and the talonavicular joint capsule (deep/floor). Contents of the anterior tarsal tunnel include the dorsalis pedis artery/vein, deep peroneal nerve, tibialis anterior tendon, extensor hallucis longus tendon, extensor digitorum longus tendon, and peroneus tertius.

The common peroneal nerve receives contributions from the L4 through S2 nerve roots.

Symptoms of tarsal tunnel syndrome may include the following:

- Motor dysfunction as a result of atrophy

- Loss of pain

- Gait abnormality

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome is directly related to compression or entrapment of the deep peroneal nerve.[2][3][4][5][6]The DPN most commonly becomes entrapped beneath the inferior extensor retinaculum secondary to acute trauma or repetitive micro-trauma, however other causes have also been reported[7][8][9][10][11]:

- Surrounding space-occupying lesions such as a ganglion cyst, intraneural ganglion, and venous engorgement of the anterior tibial veins[12][13][14]

- Osteophytes (bony overgrowth) of the metatarsals, talus, cuboid or navicular bones

- Compression by an accessory bone (os intermetatarseum)

- Hypertrophied extensor hallucis brevis muscle in athletes

- Irritation from extensor hallucis brevis tendon

- Compression from external sources such as tight-fitting shoes, athletic gear, or military equipment/boots

- Chronic prolonged stretching of the DPN or extreme plantar flexion of the ankle such as dancing, soccer, diving, Islamic Namaz praying

- Traction injury from ankle sprains or chronic ankle instability

Epidemiology

The exact incidence of anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome is unknown as the literature is limited, most likely secondary to the relative rarity of the disease and underdiagnosis. Yassin et al. reported ATTS accounts for 5% of the cases in which patients complain of numbness in their feet. Additionally, they estimated a 1% incidence rate in their practice.[15] There does not appear to be a predilection in terms of age or gender, although anecdotally, it affects athletes more often.

Pathophysiology

Anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome results from the compression of the deep peroneal nerve beneath the inferior extensor retinaculum in the anterior ankle or one of its two terminal branches more distally in the foot. Trauma, tight-fitting shoe gear, or abnormal biomechanics may be contributing factors. Systemic/metabolic risk factors have not been identified as ATTS is typically due to local factors (local edema/compression), however theoretically, any disease process that induces systemic inflammation may contribute such as diabetes mellitus or rheumatoid arthritis.

Histopathology

Increased endoneurial fluid leading to intraneural microvascular congestion is the currently understood mechanism of compression-related nerve injuries. Continued damage can result in infarction and fibrosis of the nerve.

History and Physical

A detailed patient history and clinical examination are the most important factors for an accurate diagnosis of ATTS.

Patients will typically complain of sharp shooting pain, numbness, or tingling along the distribution of the DPN or its terminal branches. Symptoms are typically intermittent and exacerbated by physical activity and alleviated by rest and elevated. The most common location of symptoms is the dorsal forefoot, more specifically the distal dorsal first webspace. The patient may recall a history of acute trauma (ankle sprain or hyper-plantar flexion injury) or repetitive microtrauma (runner or military trainee). On physical exam, repetitive percussion of the DPN may reproduce radiating paresthesias in the distal (Tinnel sign) or proximal (Valleix sign) directions. Palpation of the ankle may reveal edema or a space-occupying lesion (varicose vein or ganglion), while palpation of the foot may reveal palpable dorsal osteophytes (bone spurs). Extreme active or passive plantar flexion of the ankle may reproduce the patients' symptoms due to a stretching/compression of the nerve. A pes cavus (high arch) foot type can be present on the exam, which can contribute to dorsal compressive forces and abnormal fitting of shoe-gear.

A full lower extremity musculoskeletal and neurologic exam should be performed, including muscle strength, vibratory, light touch, temperature, and two-point discrimination exams.

In a small case series of 13 patients, Yasin et al. reported that Tinel sign was positive in 100% of patients, and a palpable bulge in anterior ankle or foot was present in 92% of ATTS cases.[15]

Evaluation

There is no specific test to diagnose anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome, and diagnosis is primarily from a comprehensive history and physical examination with additional imaging as needed based on physician preference.

Blood work to rule out diabetes should be done. Some men with reactive arthritis may develop this disorder and be positive for HLA B27. In addition, systemic arthritic disorders should be ruled out by ordering ESR, antinuclear antibody, and rheumatoid factor.

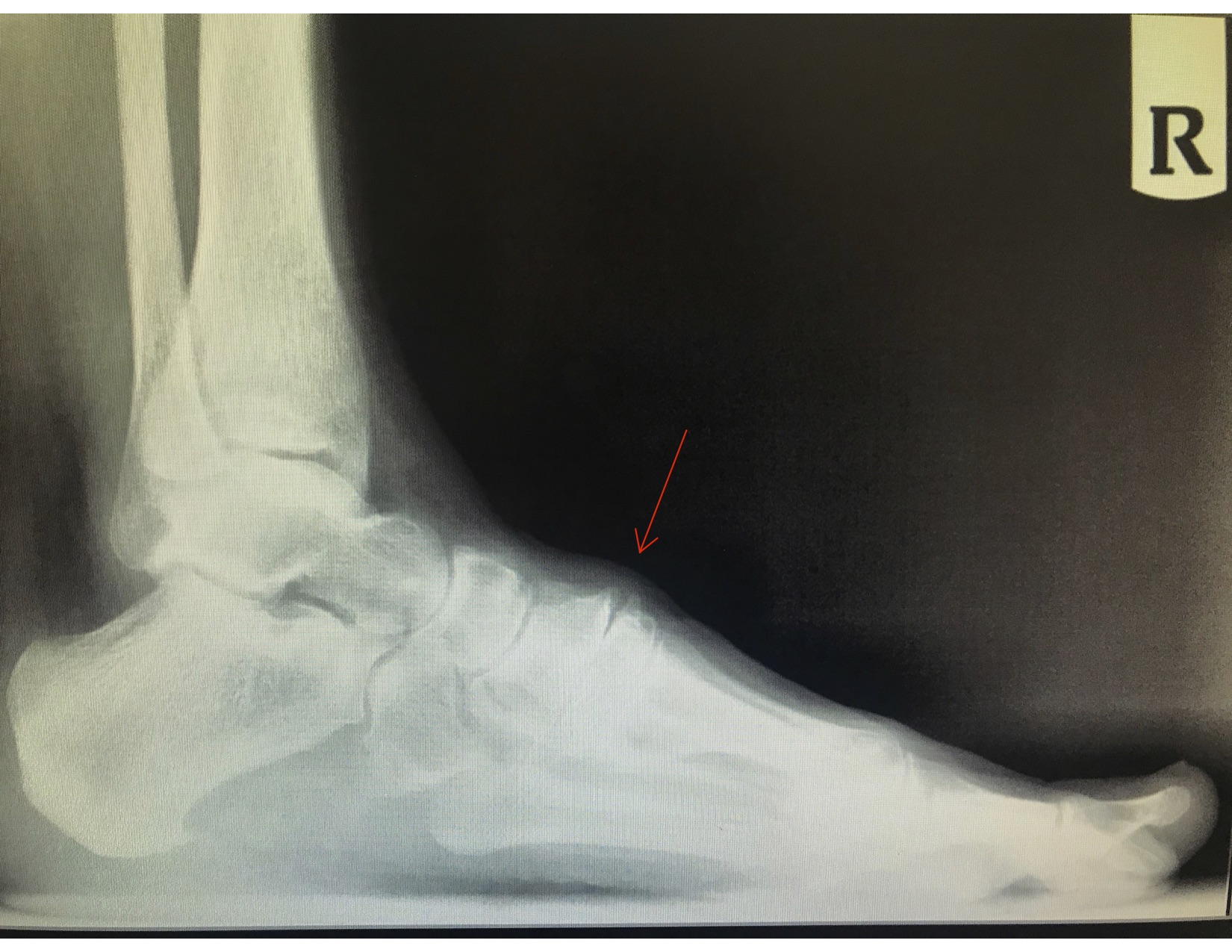

Weight-bearing radiographs of the foot and ankle are a simple, inexpensive, and readily available test that can aid in identifying overall foot-type (pes cavus) or bone spurs that may be contributing to the compression neuropathy.

In questionable clinical scenarios, nerve conduction velocity and electromyography tests may be ordered to confirm the diagnosis of ATTS and the location of the DPN entrapment. Nerve conduction studies will show deep peroneal nerve distal latency, and EMG will demonstrate findings only in the EDB muscle belly.[13]

If a soft tissue mass (ganglion or varicosities) are present on the physical exam, an MRI is an option. MR neurography is another imaging modality proven useful in diagnosing lower extremity entrapment neuropathies.[16]

High-resolution musculoskeletal ultrasound imaging is also a recommendation as electrophysiologic studies are not always reliable due to variability in peripheral nerves.[17]

Treatment / Management

The treatment of ATTS is based on the underlying etiology. Treatment should begin with a trial of non-operative methods such as:

- Changes to footwear and shoe-lacing technique modification

- Biomechanical modifications such as over-the-counter orthotics, custom orthotics, or padding

- Topical anti-inflammatory or compound creams

- Oral or topical NSAIDs or neuropathic pain medications such as gabapentin

- Perineural corticosteroid/anesthetic injection at the site of nerve entrapment

- Compression socks to alleviate local edema or varicosities

- A period of decreased athletic activity or immobilization via CAM boot

Surgical options should only be presented after failing a period of non-operative treatment. Surgery is based on the underlying etiology and may include:

- Release or decompression of the extensor retinaculum and any surrounding scar tissue

- Excision of space-occupying lesions (ganglion, varicose veins)

- Resection of osteophytes (bone spurs)

- Neurolysis, nerve wrapping, resection of neuroma or neurectomy of the DPN

Surgery is most commonly performed via an open approach; however, minimally invasive endoscopic approaches are also viable options.[18][19][15](B2)

In each surgical case, the retinaculum must be identified, and the posterior tibial nerve visualized. One should avoid injuring branches of the nerve and carefully release the fibrous bands.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of ATTS includes other conditions which can cause distal paresthesias including[20]:

- Exertional anterior compartment syndrome

- Common peroneal nerve entrapment

- Superficial peroneal nerve entrapment

- 1st inter-space neuromas (Heuter's neuroma)

- Lumbosacral radiculopathy

- Inflammatory disease states

- Primary nerve tumor

- Mid-foot retinaculum entrapment mimicking ATTS

Staging

Peripheral nerve injuries are primarily classified by the Seddon or Sunderland classification systems, which also correlate histology, MRI/Clinical presentation, and recovery.[21][22]

Prognosis

The prognosis of an anterior tarsal tunnel is variable; however, most case reports/series demonstrate good to excellent results with surgical intervention.

- Yassin et al. reported 12 out of 13 patients described their condition as greatly improved after surgery.[15]

- Dellon published a case series of 18 patients who had surgical decompression of the DPN. After a 25.9 month follow-up period, they reported 60% excellent results, 20% good results, and 20% no improvement.[23]

- Murphy performed 21 surgeries on 15 runners with persistent peripheral nerve injuries in the foot and ankle pain. He reported, 100% good to excellent results, and stated all patients returned to their pre-injury running status, including competitive athletes.[24]

Complications

Anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome that is left untreated can result in persistent pain or neuropathies of the deep peroneal nerve or its branches.

Surgical complications after decompression include nerve injury or extensor hallucis brevis wasting in the late-stage presentation.[14] Additional postoperative risks include infection, wound dehiscence, scar tissue formation, failure to resolve pain/original symptoms, and the need for additional/revisional surgery.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

In the initial 1 to 3 weeks after surgery, postoperative care focuses on immobilization and incision healing as surgery in the anterior ankle can be problematic in terms of wound dehiscence. Next, the patient should start a formal physical therapy or at-home program to enhance the strength and range of motion while decreasing edema, pain, scar tissue, and irritation of the nerve. The patient will eventually return to normal gait and athletic activities.

Consultations

- Podiatrist or podiatric surgeon

- Orthopedic surgeon

- Physical therapist

- Radiologist

- Neurologist or physiatrist

- Orthopedic nursing

Deterrence and Patient Education

No guidelines for the prevention or deterrence of anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome exist. Anecdotally, one can avoid or loosen tight-fitting shoes or athletic gear.

There is a magnitude of causes of foot and ankle pain, some of which are rare, including anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome. If a patient is experiencing foot or ankle pain with or without symptoms such as burning, numbness, tingling, and muscle weakness, they should seek the care of a medical professional.

Pearls and Other Issues

- The anterior tarsal tunnel is an entrapment neuropathy of the deep peroneal nerve or its terminal branches in the anterior ankle.

- It is relatively uncommon and often misdiagnosed.

- The etiology includes any form of compression on the DPN, typically caused by the inferior extensor retinaculum or osteophytes in the dorsal foot.

- Patients may have pain and paresthesia originating from the site of entrapment and radiating down to the dorsal foot, specifically the first webspace.

- There is no specific test to diagnose anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome, and diagnosis relies on a combination of a thorough history, physical exam, imaging, and electromyography and nerve conduction studies.

- Conservative treatment should be attempted in all patients before surgical decompression.

- Be aware of the existence of an accessory deep peroneal nerve derived from the superficial peroneal nerve.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome is a relatively rare condition that is mainly treated by podiatrists, orthopedic surgeons, and physical therapists. If surgery is the chosen therapeutic course, then other healthcare providers will join the team, such as perioperative nurses, anesthesia staff, and pharmacists. The literature is scarce, with only citations of level V case reports.

The nurses assist with coordination of care and followup. They should also assist the interprofessional team in providing patient and family education. The pharmacist should assist with providing medication reconciliation and the success of pain medication. Both the foot and nail care nurse and pharmacist should work with the clinician in making sure pain is relieved while avoiding opioid addiction. Patients may experience side effects of medications used to relieve pain, and the interprofessional team should work together to identify these side effects and offer viable alternatives. The best outcomes are achieved by a coordinated interprofessional team effort to evaluate and treat patients with anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome. [Level V]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

KOPELL HP, THOMPSON WA. Peripheral entrapment neuropathies of the lower extremity. The New England journal of medicine. 1960 Aug 14:262():56-60 [PubMed PMID: 13848498]

Sillat T, Pivec C, Bernathova M, Moritz T, Bodner G. Unusual Cause of Anterior Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome: Ultrasound Findings. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. 2017 Apr:36(4):837-839. doi: 10.7863/ultra.16.03092. Epub 2016 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 28039874]

Artico M, Stevanato G, Ionta B, Cesaroni A, Bianchi E, Morselli C, Grippaudo FR. Venous compressions of the nerves in the lower limbs. British journal of neurosurgery. 2012 Jun:26(3):386-91. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2011.631616. Epub 2011 Nov 23 [PubMed PMID: 22111921]

Cakıcı M, Ersoy O, Ince I, Kızıltepe U. Unusual localization of a primary superficial venous aneurysm: a case report. Phlebology. 2014 May:29(4):267-8. doi: 10.1258/phleb.2012.012015. Epub 2013 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 22865416]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMilants C, Wang FC, Gomulinski L, Ledon F, Petrover D, Bonnet R, Crielaard JM, Kaux JF. [The anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome: a case report]. Revue medicale de Liege. 2015 Jul-Aug:70(7-8):400-4 [PubMed PMID: 26376569]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHuang KC, Chen YJ, Hsu RW. Anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome: case report. Changgeng yi xue za zhi. 1999 Sep:22(3):503-7 [PubMed PMID: 10584426]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNakasa T, Fukuhara K, Adachi N, Ochi M. Painful os intermetatarseum in athletes: report of four cases and review of the literature. Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery. 2007 May:127(4):261-4 [PubMed PMID: 16850328]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKnackfuss IG, Giordano V, Nogueira M, Giordano M. Compression of the medial branch of the deep peroneal nerve, relieved by excision of an os intermetatarseum. A case report. Acta orthopaedica Belgica. 2003 Dec:69(6):568-70 [PubMed PMID: 14748119]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNoguchi M, Iwata Y, Miura K, Kusaka Y. A painful os intermetatarseum in a soccer player: a case report. Foot & ankle international. 2000 Dec:21(12):1040-2 [PubMed PMID: 11139035]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTennant JN, Rungprai C, Phisitkul P. Bilateral anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome variant secondary to extensor hallucis brevis muscle hypertrophy in a ballet dancer: a case report. Foot and ankle surgery : official journal of the European Society of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. 2014 Dec:20(4):e56-8. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2014.07.003. Epub 2014 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 25457672]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceReed SC, Wright CS. Compression of the deep branch of the peroneal nerve by the extensor hallucis brevis muscle: a variation of the anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome. Canadian journal of surgery. Journal canadien de chirurgie. 1995 Dec:38(6):545-6 [PubMed PMID: 7497372]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKanbe K, Kubota H, Shirakura K, Hasegawa A, Udagawa E. Entrapment neuropathy of the deep peroneal nerve associated with the extensor hallucis brevis. The Journal of foot and ankle surgery : official publication of the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. 1995 Nov-Dec:34(6):560-2 [PubMed PMID: 8646207]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAkyüz G, Us O, Türan B, Kayhan O, Canbulat N, Yilmar IT. Anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome. Electromyography and clinical neurophysiology. 2000 Mar:40(2):123-8 [PubMed PMID: 10746190]

Ferkel E, Davis WH, Ellington JK. Entrapment Neuropathies of the Foot and Ankle. Clinics in sports medicine. 2015 Oct:34(4):791-801. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2015.06.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26409596]

Yassin M, Garti A, Weissbrot M, Heller E, Robinson D. Treatment of anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome through an endoscopic or open technique. Foot (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2015 Sep:25(3):148-51. doi: 10.1016/j.foot.2015.05.007. Epub 2015 May 29 [PubMed PMID: 26209470]

Garwood ER, Duarte A, Bencardino JT. MR Imaging of Entrapment Neuropathies of the Lower Extremity. Radiologic clinics of North America. 2018 Nov:56(6):997-1012. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2018.06.012. Epub 2018 Jul 13 [PubMed PMID: 30322495]

Chari B, McNally E. Nerve Entrapment in Ankle and Foot: Ultrasound Imaging. Seminars in musculoskeletal radiology. 2018 Jul:22(3):354-363. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1648252. Epub 2018 May 23 [PubMed PMID: 29791963]

Ducic I, Felder JM 3rd. Minimally invasive peripheral nerve surgery: peroneal nerve neurolysis. Microsurgery. 2012 Jan:32(1):26-30. doi: 10.1002/micr.20959. Epub 2011 Oct 17 [PubMed PMID: 22002885]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLui TH. Endoscopic anterior tarsal tunnel release: a case report. The Journal of foot and ankle surgery : official publication of the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. 2014 Mar-Apr:53(2):186-8. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2013.12.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24556485]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSwathi, Nellithala GG, Athavale SA. Mid-foot retinaculum: an unrecognized entity. Anatomy & cell biology. 2017 Sep:50(3):171-174. doi: 10.5115/acb.2017.50.3.171. Epub 2017 Sep 20 [PubMed PMID: 29043094]

Seddon HJ. Peripheral Nerve Injuries. Glasgow medical journal. 1943 Mar:139(3):61-75 [PubMed PMID: 30437076]

SUNDERLAND S. A classification of peripheral nerve injuries producing loss of function. Brain : a journal of neurology. 1951 Dec:74(4):491-516 [PubMed PMID: 14895767]

Dellon AL. Deep peroneal nerve entrapment on the dorsum of the foot. Foot & ankle. 1990 Oct:11(2):73-80 [PubMed PMID: 2265812]

Murphy PC, Baxter DE. Nerve entrapment of the foot and ankle in runners. Clinics in sports medicine. 1985 Oct:4(4):753-63 [PubMed PMID: 4053199]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence