Introduction

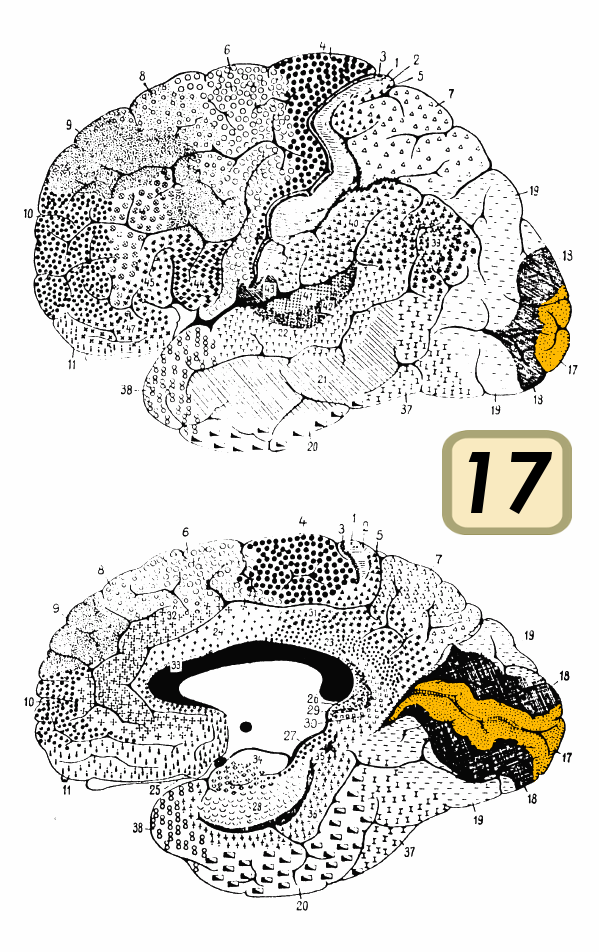

The visual cortex is the primary cortical region of the brain that receives, integrates, and processes visual information relayed from the retinas. It is in the occipital lobe of the primary cerebral cortex, which is in the most posterior region of the brain. The visual cortex divides into five different areas (V1 to V5) based on function and structure. Visual information from the retinas that are traveling to the visual cortex first passes through the thalamus, where it synapses in a nucleus called the lateral geniculate. This information then leaves the lateral geniculate and travels to V1, the first area of the visual cortex. V1 is also known as the primary visual cortex and centers around the calcarine sulcus.[1]

Each hemisphere has its own visual cortex, which receives information from the contralateral visual field. In other words, the right cortical areas process information from the left eye, and the left processes information from the right eye. The primary purpose of the visual cortex is to receive, segment, and integrate visual information. The processed information from the visual cortex is subsequently sent to other regions of the brain to be analyzed and utilized. This process is highly specialized and allows the brain to recognize objects and patterns quickly without a significant conscious effort.

One advantage of this specialization is that other cortical regions are free to perform other computations, such as those responsible for executive functioning and decision-making. However, since visual processing is mostly an unconscious process, it can lead to misinterpretations of visual data, which are demonstrated by the efficacy of visual illusions.[2]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The primary function of the visual cortex is to process visual information. The visual cortex subdivides into five different areas based on structural and functional classifications. The hypothesis is that as visual information gets passed along, each subsequent cortical area is more specialized than the last. Neurons in the visual cortex often respond to stimuli within a fixed receptive field, the area of the visual field that they respond to, and the neurons in each visual area respond to different types of stimuli. One of the best-studied examples of specialized cells is that of simple and complex cells. Simple cells, which are found mostly in V1, respond to specific types of visual cues, such as the orientation of edges and lines. Complex cells, which occur in V1-V3, are like simple cells in that they respond to edges and orientations, but they do not appear to represent a single receptive field. Instead, they respond to the summation of several receptive fields that become integrated from many simple cells. Also, complex cells respond preferentially to movement in specific directions. Other examples of specialized cells include end-stopped cells, which detect line endings, and bar and grating cells.[3]

V1 is the first of the cortical regions to receive and process information and also the best-understood portion of the visual cortex. V1 is divided up into six distinct layers, each comprising different cell types and functions. Notably, layer 4 is the location that receives information from the lateral geniculate. Layer 4 is also the layer that has the highest concentration of simple cells. Complex cells, on the other hand, can be found in layers 2, 3, and 6. V1 responds to simple visual components such as orientation and direction. The summation of this information provides the foundation for more complicated pattern recognition later in the visual stream.[4]

V2 receives integrated information from V1 and subsequently has an increased level of complexity and response patterns to objects. Researchers have recorded cells in this region responding to differences in color, spatial frequency, moderately complex patterns, and object orientation.[5] V2 sends feedback connections to V1 and has feedforward connections with V3-V5. Information leaving the second visual area splits into the dorsal and ventral streams, which specialize in processing different aspects of visual information. The former is often described as being concerned with object recognition, while the latter focuses on spatial tasks and visual-motor skills.

As visual information disseminates throughout the brain, more specialized cells are present. The theory is that there are specialized cells or groups of cells that learn to respond to particular objects; this would allow for the immediate recognition of things seen previously.[6] Also, similar cells could be responsible for other important visual information, such as spatial orientation.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Branches of the posterior cerebral artery supply the visual cortex. These branches include the posterior temporal, parietooccipital, and calcarine arteries.[7]

Surgical Considerations

Many surgical cases show the risk of damage to the visual cortex.[8] The visual cortex is susceptible to mechanical damage that can be caused by surgeons attempting to remove tumors or other masses that are present in this area. To minimize the possibility of causing cortical blindness, surgeons will often use a technique called cortical mapping to try and localize important regions of visual processing.

Cortical mapping allows surgeons to localize specific regions of the visual cortex by stimulating the brain parenchyma with an electrode and asking the patient to report what they saw. This patient feedback is crucial when a differential diagnosis of malignancy from normal brain tissue is difficult. With this and other similar techniques, surgeons can make informed decisions on where to cut and what structures they can safely remove.

Clinical Significance

Cortical blindness refers to any partial or complete visual deficit that is caused by damage to the visual cortex in the occipital lobe.[9] This condition requires differentiation from other types of blindness that are caused by damage to other parts of the visual stream. Unilateral lesions can lead to homonymous visual field deficits or, if small, scotomas. Bilateral lesions can cause complete cortical blindness and can sometimes be accompanied by a condition called Anton-Babinski syndrome, which is when a patient is blind but denies having any visual deficit.[10][11]

Cortical blindness can result from any disruption or damage to the normal architecture of the visual cortex. Most commonly, this occurs in patients with a stroke in the territory of the posterior cerebral artery.[7] If an ischemic stroke causes cortical blindness, there is the possibility that visual impairment is reversible through reperfusion. However, many patients do not fully regain cortical function and maintain some level of cortical visual impairment. Prosopagnosia is a term referring to the inability to recognize faces and can result from a stroke that inhibits information traveling from the visual cortex to the inferior temporal cortex. Other non-stroke causes of cortical blindness include infection, eclampsia, traumatic brain injury, encephalitis, meningitis, medications, and hyperammonemia.

Media

References

Tran A, MacLean MW, Hadid V, Lazzouni L, Nguyen DK, Tremblay J, Dehaes M, Lepore F. Neuronal mechanisms of motion detection underlying blindsight assessed by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Neuropsychologia. 2019 May:128():187-197. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2019.02.012. Epub 2019 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 30825453]

Goodale MA. Transforming vision into action. Vision research. 2011 Jul 1:51(13):1567-87. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2010.07.027. Epub 2010 Aug 4 [PubMed PMID: 20691202]

Goodale MA, Milner AD. Separate visual pathways for perception and action. Trends in neurosciences. 1992 Jan:15(1):20-5 [PubMed PMID: 1374953]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDeAngelis GC, Ohzawa I, Freeman RD. Receptive-field dynamics in the central visual pathways. Trends in neurosciences. 1995 Oct:18(10):451-8 [PubMed PMID: 8545912]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAnzai A, Peng X, Van Essen DC. Neurons in monkey visual area V2 encode combinations of orientations. Nature neuroscience. 2007 Oct:10(10):1313-21 [PubMed PMID: 17873872]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFournier J, Müller CM, Schneider I, Laurent G. Spatial Information in a Non-retinotopic Visual Cortex. Neuron. 2018 Jan 3:97(1):164-180.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.11.017. Epub 2017 Dec 14 [PubMed PMID: 29249282]

Sceleanu A. [Arteries of visual cortex]. Oftalmologia (Bucharest, Romania : 1990). 2002:54(3):87-90 [PubMed PMID: 12723208]

Sanai N, Berger MS. Recent surgical management of gliomas. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2012:746():12-25. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-3146-6_2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22639156]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAldrich MS, Alessi AG, Beck RW, Gilman S. Cortical blindness: etiology, diagnosis, and prognosis. Annals of neurology. 1987 Feb:21(2):149-58 [PubMed PMID: 3827223]

Chen JJ, Chang HF, Hsu YC, Chen DL. Anton-Babinski syndrome in an old patient: a case report and literature review. Psychogeriatrics : the official journal of the Japanese Psychogeriatric Society. 2015 Mar:15(1):58-61. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12064. Epub 2014 Dec 16 [PubMed PMID: 25515048]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceM Das J, Naqvi IA. Anton Syndrome. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30844182]