Introduction

Chagas disease, or American Trypanosomiasis, is a potentially life-threatening zoonotic illness caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, first described in 1909 by Brazilian physician Carlos Chagas.[1] The disease is primarily found in Central and South America, Trinidad, and the southern United States, with rural areas being most affected due to the presence of the reduviid bug (also known as the triatomine or "kissing bug"). The term kissing bug is a colloquial term that refers to a variety of species of insects in the Triatominae family (triatomines) that commonly seek out uncovered host mucosal surfaces and thus will frequently bite the face.[2][3][4]

The vector-borne disease is transmitted primarily via contact with contaminated excrement of the reduviid bug into an open wound (eg, the bite of the bug itself), with the insect serving as the intermediate host for the parasite and humans and other mammals serving as definitive hosts.[5] Vertical transmission between mother and fetus is also possible. Other modes of transmission include transfusion of blood products, transplant of an infected organ, or consumption of infected food or drinks.

Chagas disease has 2 phases: acute and chronic. The acute phase, lasting about 2 months, often presents with mild or no symptoms, though fever, localized edema, and Romana’s sign (unilateral eyelid swelling) may occur. In the chronic phase, which affects approximately 30% of infected individuals, cardiac complications, eg, cardiomegaly, heart failure, and arrhythmias, are common, while gastrointestinal involvement may lead to megacolon or megaesophagus.[6] Diagnosis in the acute phase relies on microscopic detection of the parasite or PCR testing, while chronic cases are confirmed through serological tests.

Treatment includes antiparasitic medications, nifurtimox and benznidazole, which are most effective in the acute phase. In chronic cases, management focuses on treating complications, with some patients requiring pacemakers, defibrillators, or surgical interventions.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Chagas disease is a vector-borne illness most commonly transmitted through contact with the contaminated feces and urine of the reduviid or kissing bug. This insect, in turn, carries the causative agent—the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. Over 140 species of triatomines have been identified, but only about 40 species are found in North America, where native infections occur. In the United States, at least 11 triatomine species have been confirmed to transmit the disease, along with 24 known hosts. The most common species in the southern United States are Triatoma sanguisuga and Triatoma gerstaeckeri. The primary vectors in Mexico, Central America, and South America are Rhodnius prolixus and Triatoma dimidiata.

The insects often lay dormant during the daytime, hiding in cracks in housing or agricultural structures and emerging at night to feed. Both sexes of reduviid bugs feed in this way, and female kissing bugs must additionally take blood meals to lay their eggs. As it takes the meal or soon afterward, the insect defecates and expels parasites in the feces and urine near the feeding bite. Local irritation at the bite site causes the person to instinctively rub the area, smearing the parasite-laden excrement into the open wound. The parasite can also enter through contact with the mucous membranes if the person touches their mouth or eyes with contaminated skin. Feces of infected reduviid bugs carry the largest number of the infectious trypomastigote form.[7]

Other mode transmissions include:

Epidemiology

Chagas is endemic in Latin America, from the southern United States to northern Argentina and Chile.[10] However, the distribution of the disease is changing due to the relocation of individuals from the endemic countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 6 to 7 million people are currently infected with T. cruzi, causing 12,000 deaths annually, with 75 million people at risk of contracting the disease. In endemic regions of the Americas, approximately 28,000 new cases are reported annually.[11] Of those infected with the parasite, 1 in 10 will develop cardiac manifestations.[12] In the most affected regions, countries (eg, Bolivia) have up to 6 cases per every 100 people. Chagas disease has traditionally been a disease that occurs in poor rural areas where the kissing bug thrives.[3]

Domestic and wild mammals are also common hosts for this parasite. The primary transmission route occurs through infected reduviid bugs, which can be found in cracks indoors or on the roofs of substandard housing made from mud, straw, or palm thatch. Outdoor locations include animal nests, agricultural buildings (eg, barns and chicken coops), and tree bark or logs.[13] Children are most commonly affected, followed by women and then men.

In the United States, more than 300,000 Latin American immigrants are estimated to be currently infected with Chagas disease.[11][14] Reduviid bugs are frequently found in border states (eg, Texas) and commonly test positive for T. cruzi.[15] Kissing bug bites have been confirmed as far north as Delaware, with reports stretching to Maine.[16][17] Factors that influence the spread of disease are a combination of vector-borne transmission of infected individuals and the migration of people from rural to urban areas.[9] Chagas cardiomyopathy in nonendemic regions like the United States is likely underestimated.[18]

The presence of T. cruzi in blood donors from United States samples is about 0.02%. If transfused with infected blood, approximately 10% to 20% of recipients will contract Chagas disease.[2] Trypanosoma cruzi infection can also be transmitted from organs transplanted from an infected individual. Transmission rates vary on the organ transplanted, ranging from 18% to 19% for the kidney and 29% for the liver. A heart transplant from infected donors is contraindicated. T. cruzi reactivation can occur in up to 20% of HIV-infected patients.

Pathophysiology

The T. Cruzi Parasite Life Cycle

T. cruzi, in its leishmanial (trypanomastigote) form, is ingested by the vector reduviid bug when it takes a blood meal from an infected host. The trypomastigotes transform into epimastigotes in the insect's midgut, where they multiply and become flagellated in the midgut. Finally, they mature to the infective form in the hindgut, where they are excreted to infect a new host after the insect bites again (see Image. T. Cruzi Parasite Life Cycle).

When the reduviid bug bites and takes a blood meal, the metacyclic trypomastigotes are passed in the insect's feces near the open bite wound. Local irritation causes the mammal to scratch or contact the area, introducing the trypomastigotes to the mammalian host's bloodstream through the open bite. Alternatively, the mammalian host may innoculate themselves later by touching mucous membranes with a contaminated appendage.

After the parasite enters through an open wound or mucous membrane, the metacyclic trypomastigote penetrates various host cells near the site of infection, where they transform into amastigotes intracellularly. The amastigote stage of the parasites is found mainly inside pseudocysts located in muscle or nerve cells, where they multiply via binary fission. The intracellular amastigotes transform into trypanomastigotes, resulting in cell rupture and the entrance of the trypanomastigotes into the host bloodstream. These circulating trypanomastigotes can then infect additional host cells, and this host auto-infection cycle repeats, leading to clinical disease. If such a host is then bitten by another reduviid bug, these circulating trypomastigotes are then uptaken with the blood meal by the reduviid vector, facilitating transmission to additional hosts.[19]

Clinical Phases

Chagas disease has 2 clinical phases: acute and chronic.

Acute infection

Signs and symptoms are directly related to the T. cruzi parasite's replication and the host immune response to this replication. During this phase, the cycle of replication and auto-infection results in circulating trypomastigotes in the bloodstream, and the host's immune system produces antibodies to combat the infection. This phase lasts several weeks after initial infection and is primarily driven by host immune cells targeting intracellular pathogens, eg, natural killer T-cells and macrophages.[3]

Chronic infection

In the absence of treatment, host immune responses will ultimately control the parasite replication and resolution of symptoms in 4 to 8 weeks.[9] These patients remain asymptomatic and carry the infection for life. However, untreated infection can lead to ongoing circulation and deposition of parasite trypomastigotes into various cells throughout the host's body, and clinical disease is the result of years of continuing replication, circulation, and immune response, ultimately leading to end-organ damage in the host.[20]

After several decades in the chronically infected, approximately 30% will develop significant gastrointestinal or cardiac sequelae.[4][11] The parasites show a predilection for infecting striated muscle cells, with significant parasite load detectable in cardiac muscle early in the chronic infection course. Late in the chronic phase of infection, parasite levels drop to barely detectable levels as the number of viable myocardial cells decreases.[20][21] This leads to local immune response inciting fibrosis of the cardiac muscle, leading to cardiomegaly and an overall decrease of viable myocardium. Approximately 20% to 30% will develop cardiomyopathy.[9] Chagas cardiomyopathy can result in conduction delay, dysrhythmia, and dilated nonischemic cardiomyopathy.[9][18]

A less common sequela from Chagas is gastrointestinal disorders. The parasite routinely infects nerve cells in the gastrointestinal tract, leading to a profound loss of nerve endings in the digestive system, leading to decreased peristalsis in the esophagus and loss of function in the esophagus, as well as in the colon, with this loss of neurologic control of these organs being the underlying cause of organ dysfunction, as well as interrupting the blood supply. Disorders of motility resulting in dilation, eg, achalasia or megacolon, can also result.[21][9]

Reactivation of Chagas disease following immunosuppression results in parasite replication, parasitemia, and a clinical picture similar to acute infection, which is often more severe.[22][23] Common predisposing conditions include organ transplantation, untreated human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), or chemotherapy.[22] Immunosuppression from corticosteroids does not appear to increase rates of reactivation.[23]

Histopathology

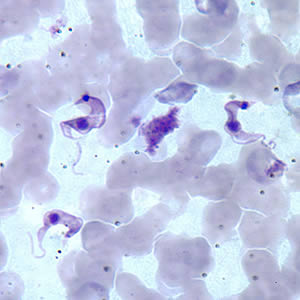

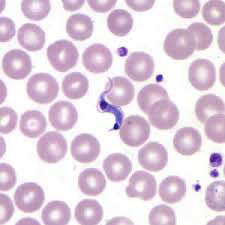

Microscopic detection of T. cruzi parasites is diagnostic for Chagas disease. Motile parasites can be detected microscopically by examining fresh, anticoagulated blood or the buffy coat of a fresh blood sample (see Image. Chagas Disease).[9] Alternatively, both thick and thin peripheral blood smears can be stained with Giemsa, where parasites can be visualized with a sensitivity ranging from 34% to 85% (see Image. Trypanosoma Cruzi).[3][2] Microscopically, the T. cruzi parasite has an undulating cell membrane with a flagellum, a visible nucleus, and a hallmark kinetoplast structure, distinguishing T. cruzi from other Trypanosoma species.[24]

History and Physical

Clinical Features of Chagas Disease

The clinical features of Chagas disease depend on its phase: acute or chronic. In either case, though possible, it is rare for a patient to remember or report a reduviid bug bite. Therefore, the astute clinician must consider Chagas disease as part of a broad differential diagnosis, especially in endemic areas.

Acute phase

The acute phase of Chagas disease lasts for approximately 2 months following infection from a bite, and symptoms may be very mild or absent altogether. Patients may rarely present with a skin lesion or visible bite with local irritation but, more commonly, will experience fever, localized edema, lymphadenopathy, myalgias, pallor, shortness of breath, and abdominal or chest pains.[25][26]

Intense local inflammation with uniocular conjunctivitis, or a purplish discoloration of 1 eyelid, is known as a Chagoma or Romana's sign and is a hallmark of Chagas disease (see Image. Romana's Sign).[27] Thus, a comprehensive physical examination is required. Care should be taken to perform a thorough skin examination and diligent heart, lung, abdominal, and extremity examinations to assess for lymphadenopathy. A small subset of patients will experience an anaphylactic reaction to the kissing bug bite, with presenting signs and symptoms including acute onset of urticarial rash, flushing, difficulty breathing, wheezing, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, tachycardia, and edema.[28][29] Congenital infections may cause premature birth, low birth weight, fever, anemia, and hypotonicity.[2][3]

Chronic phase

An estimated 30% of Chagas patients will have cardiac involvement and may thus present with fever, cardiomegaly, apical aneurysms, or electrocardiography (ECG) abnormalities. Patients may present with heart failure, and subsequent cardiac workup may lead to the initial diagnosis of Chagas. Approximately 10% of patients may have gastrointestinal tract involvement and may present with fever, megaesophagus, or megacolon due to the destruction of myenteric plexus and constipation. Such gastrointestinal complaints of chronic Chagas may also be the presenting/diagnostic complaints for the patient.[30] Clinical manifestations of Chagas reactivation often occur in the setting of immunosuppression and result in an acute illness that may include chagoma, panniculitis, myocarditis, or meningoencephalitis.[23]

Patients living in or from endemic areas presenting with signs and symptoms worrisome for heart failure or with intractable constipation warrant a thorough physical examination with special attention paid to heart, lung, abdominal, and extremity examinations. Signs of cardiomegaly, eg, a displaced point of maximal impulse, diminished pulse pressures, or sinus tachycardia, may be present.[31] Features of right heart failure, including bibasilar pulmonary rales or bipedal pitting edema, may be present. Abdominal distention with a soft abdomen and diminished bowel sounds may be present. Digital rectal examination may reveal hardened or impacted stool.[32] The abdominal examination may also reveal hepatosplenomegaly, and the conjunctival exam may reveal pallor from chronic anemia.[33][34]

Evaluation

The presenting symptoms will guide the investigations when evaluating a patient for potential Chagas disease.

Laboratory Studies

Diagnosis is established during the acute phase by detecting the parasite microscopically, from a fresh preparation of anticoagulated blood or buffy coat due to the high level of parasitemia. However, levels may decrease within 90 days of infection and may be undetectable by microscopy as the sensitivity of the test decreases and as the disease progresses from acute to chronic. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is another diagnostic tool that may be used during the acute phase, monitoring for acute infection in organ transplant recipients or following accidental exposures. PCR assays can demonstrate positive results days to weeks before a peripheral blood smear detects circulating trypomastigotes.

Additional Diagnostic Studies

When examining a patient with suspected chronic Chagas disease, further investigations will focus on the organ system dysfunction being assessed. Long-term cardiac manifestations are most common; an initial workup will often entail an ECG, and chest x-ray and echocardiography may also be indicated. Signs of cardiomegaly will be evident on all 3, and diminished ejection fraction may be demonstrated on echocardiography.[35][36] Common ECG findings are right bundle branch block, left anterior fascicular block, first-degree AV node block, and atrial flutter/fibrillation.[37]

Similarly, if a patient presents with gastrointestinal complaints, a series of abdominal x-rays may demonstrate pseudo-obstruction of the bowels, and a megacolon may be evident.[38] Ancillary testing for those with gastrointestinal symptoms may consist of a barium swallow and barium enema. The diagnosis of Chagas is confirmed via the detection of IgG antibodies to T. cruzi in chronic infections.[39]

Treatment / Management

Acute Chagas Disease Treatment

Clinicians should consider antitrypanosomal treatment for acute, congenital, and reactivation infections, indeterminate forms, women of childbearing age, accidental high-risk exposures, and chronic infections in the pediatric population.[6] Treatment may also be indicated for immunosuppressed patients.[11] Treatments for Chagas disease include nifurtimox and benznidazole, with >80% success during the acute phase but with no effect on the amastigote stage.[40](B3)

Benznidazole and nifurtimox are the only approved antitrypanosomal drugs available. Based on the 2018 Pan American Health Organization guideline, evidence to suggest which medication should be used as the first-line option is lacking; however, in the United States, benznidazole is used more often due to availability.[11] Benznidazole was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017 with a recommended dosage of 5 to 10 mg/kg/day divided every 12 hours for 30 to 60 days.[9][11] Pediatric dosing also includes a 60-day weight-based regimen. A common adverse effect is dermatitis; more serious adverse effects include myelosuppression and peripheral neuropathy.[22] The presence of myelosuppression or neuropathy is an indication to discontinue treatment immediately. Nifurtimox is the other antitrypanosomal therapy but is not currently FDA-approved. However, nifurtimox can be obtained through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) under an investigational protocol. Dosing is 8 to 10 mg/kg/day divided into 3 doses for 60 to 120 days. Pediatric dosing also includes a weight-based regimen.[11] Gastrointestinal adverse effects are very common with nifurtimox and may include nausea and vomiting.[9] More serious adverse effects can include neurotoxicity, including neurocognitive effects or neuropathy.[22][9](B3)

Cure rates are variable and dependent on several factors, including the patient's age, disease stage, and infection duration. During the acute phase, cure rates range from 80% to 90% and 20% to 60% in chronic disease.[22][9] Children generally respond better to therapy; earlier screening and treatment lead to a higher negative seroconversion rate.[9][6] Transplant patients with prior infection should undergo monitoring at intervals similar to monitoring for rejection and if concerns for an acute infection or reactivation are present.[22](B3)

Management of Chronic Chagas Disease

Treatment for chronic Chagas disease is dependent on which organ is involved. Treatment of Chagas heart failure is largely symptomatic, with pacing and defibrillation used to ameliorate life-threatening arrhythmias. Simply treating the patients with antiparasitic medications does not halt or reverse the end-organ symptoms in chronic Chagas disease.[41] Trypanocidal therapy for established Chagas cardiomyopathy is controversial. In a randomized trial, trypanocidal treatment for patients with Chagas cardiomyopathy resulted in a higher negative seroconversion rate but did not appear to improve clinical outcomes.[42] Despite largely negative results, some authors continue to advocate for treating Chagas cardiomyopathy with trypanocidal therapy.[43] Current thinking revolves around a parasite-driven systemic immune response that leads to end-organ damage, and there is much ongoing research into the use of immunomodulating medications in the treatment of these patients.[44][45](A1)

End-stage cardiac disease from Chagas is treated in much the same way as other forms of end-stage heart failure, with rate and rhythm control, prophylaxis for thromboembolism, and implanted defibrillators. Chagas cardiomyopathy is not a contraindication for heart transplantation, though the required immunosuppression makes reactivation of the latent disease highly likely.[46]

End-stage colon dysfunction, also called chagasic megacolon, may require surgical intervention. The Duhamel-Haddad procedure involves resection of the dilated, hypofunctional sections of the colon and has also been described with frozen section controls to evaluate for subclinical neuronal loss.[47][48] Other operations have been described, including partial sigmoidectomy with loop interposition, all to avoid a permanent ostomy.[49][50]

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses may be broad since signs and symptoms of Chagas disease are nonspecific and may include dysfunction of multiple organ systems. During the acute phase, symptoms of fever and malaise can mimic many other febrile illnesses. Unilateral palpebral edema could be mistaken for periorbital cellulitis. A chagoma could be mistaken for another arthropod bite or other dermatologic conditions of localized inflammation. Differential diagnoses that should also be considered when evaluating Chagas disease include:

- Esophageal motility disorders

- Esophageal rupture

- Esophageal spasm

- Esophagitis

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- Leishmaniasis

- Malaria

- Meningitis

- Myocardial infarction

- Myocardial rupture

- Congestive heart failure

Prognosis

The overall prognosis depends upon when the disease is diagnosed and treatment begins. Those patients diagnosed and potentially cured in the acute phase, before end-organ damage has occurred, have an overall favorable prognosis. However, rare reports of death from acute Chagas exist, primarily due to acute myocarditis.[51] In the acute phase, 1% to 5% of patients will develop severe disease, with a mortality rate of 0.2% to 0.5%.[3]

Patients with chronic Chagas disease have a prognosis dependent upon the organ function (especially cardiac) at the time of diagnosis and treatment. Patients with Chagas cardiomyopathy have higher mortality and morbidity when compared to other causes of nonischemic heart disease, and overall, lower quality of life and lower life expectancy than those not infected.[52] Of those who develop chronic infection, approximately 10% develop symptomatic organ dysfunction, and 20% develop asymptomatic organ involvement.[17] Studies estimate that approximately 12,000 people per year die from Chagas disease. Significant variability in morbidity and mortality based on the route of infection exists.[3]

Complications

Chronic cardiomyopathy and heart failure are the principal complications of untreated Chagas disease, though megacolon and other chronic intestinal dysmotility are also well-described.[53] Other rarer complications include esophageal dilatation and dysmotility, as well as brain abscess formation.[54]

During the acute phase of infection, serious complications include:

- Myocarditis

- Pericardial effusion

- Encephalitis

- Meningoencephalitis

During the chronic phase, complications include:

- Heart failure

- Arrhythmias

- Thromboembolic disease

- Megaesophagus

- Megacolon

- Neuropathy

Consultations

Once the diagnosis is made, consultation with an infectious disease specialist is recommended. Other important specialists can include cardiologists and gastroenterologists.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Preventing Chagas disease primarily relies on public health initiatives and reducing exposure to the reduviid bug in endemic regions. Public health campaigns should focus on educating communities about the bug’s habitats, its nocturnal feeding behavior, and ways to minimize contact. Encouraging the use of insecticide-treated bed nets, sealing cracks in walls and roofs, and improving housing conditions—such as using plastered walls and screened windows—can significantly reduce the risk of infestation.[24] Additionally, community-based vector control programs, including insecticide spraying and environmental management, play a crucial role in reducing transmission. Proper food hygiene is also essential, as oral transmission through contaminated food or beverages has been reported in some outbreaks.

Clinician awareness is equally vital, particularly in endemic areas and among healthcare practitioners treating at-risk populations, including travelers, immigrants, and those receiving blood transfusions or organ transplants.[55] Physicians should educate patients about potential transmission routes, the importance of early diagnosis, and available treatment options. Pregnant women in endemic regions should receive counseling on congenital transmission risks, and blood banks should ensure proper screening procedures. By improving public awareness and clinician competence, preventive efforts can significantly decrease the burden of Chagas disease and reduce its long-term health consequences.[55]

Pearls and Other Issues

Currently, Chagas disease has no vaccine. The main methods for preventing transmission include education, improved housing, vector control using bed netting, and screening donated blood and children in endemic areas.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of Chagas disease require a collaborative, interprofessional approach to ensure timely detection, effective treatment, and improved patient outcomes. Physicians, including infectious disease specialists, cardiologists, emergency physicians, gastroenterologists, and internists, play a critical role in recognizing symptoms, ordering appropriate diagnostic tests, and implementing treatment strategies. Since the disease is rare in North America, clinicians must maintain a high index of suspicion when evaluating patients from endemic regions. Advanced practitioners and nurses are essential in patient education, monitoring treatment adherence, and providing long-term care, particularly for those with severe residual complications affecting the heart and gastrointestinal system. Pharmacists contribute by ensuring proper medication use, managing potential adverse effects of antiparasitic treatments like benznidazole and nifurtimox, and advising on drug interactions, especially for patients with cardiac involvement requiring additional therapies.

Effective interprofessional communication and care coordination are crucial to enhancing patient-centered care, improving outcomes, and ensuring patient safety. Close collaboration between healthcare professionals allows for comprehensive management, addressing both acute infection and chronic complications. Nurses and advanced practitioners serve as primary contact points for patient education, reinforcing the importance of vector control, screening, and symptom monitoring. Social workers and public health professionals are key in community outreach, helping at-risk populations access preventive resources and healthcare services. Coordinated efforts between primary care clinicians and specialists ensure that patients receive long-term follow-up, particularly those with cardiac complications requiring ongoing monitoring. A well-integrated healthcare team enhances patient safety and treatment adherence, and public health efforts can be strengthened to reduce transmission risks.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

T. Cruzi Parasite Life Cycle. Illustration of the various phases of the T. Cruzi life cycle.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Steverding D. The history of Chagas disease. Parasites & vectors. 2014 Jul 10:7():317. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-317. Epub 2014 Jul 10 [PubMed PMID: 25011546]

Guarner J. Chagas disease as example of a reemerging parasite. Seminars in diagnostic pathology. 2019 May:36(3):164-169. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2019.04.008. Epub 2019 Apr 17 [PubMed PMID: 31006555]

Pérez-Molina JA, Molina I. Chagas disease. Lancet (London, England). 2018 Jan 6:391(10115):82-94. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31612-4. Epub 2017 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 28673423]

Montgomery SP, Parise ME, Dotson EM, Bialek SR. What Do We Know About Chagas Disease in the United States? The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2016 Dec 7:95(6):1225-1227. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0213. Epub 2016 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 27402515]

Martinez SJ, Romano PS, Engman DM. Precision Health for Chagas Disease: Integrating Parasite and Host Factors to Predict Outcome of Infection and Response to Therapy. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology. 2020:10():210. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00210. Epub 2020 May 8 [PubMed PMID: 32457849]

Echeverria LE, Morillo CA. American Trypanosomiasis (Chagas Disease). Infectious disease clinics of North America. 2019 Mar:33(1):119-134. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2018.10.015. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30712757]

Padilla N A, Moncayo AL, Keil CB, Grijalva MJ, Villacís AG. Life Cycle, Feeding, and Defecation Patterns of Triatoma carrioni (Hemiptera: Reduviidae), Under Laboratory Conditions. Journal of medical entomology. 2019 Apr 16:56(3):617-624. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjz004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30768666]

Coura JR, Viñas PA, Junqueira AC. Ecoepidemiology, short history and control of Chagas disease in the endemic countries and the new challenge for non-endemic countries. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2014 Nov:109(7):856-62 [PubMed PMID: 25410988]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBern C. Chagas' Disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2015 Jul 30:373(5):456-66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1410150. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26222561]

Martins-Melo FR, Carneiro M, Ribeiro ALP, Bezerra JMT, Werneck GL. Burden of Chagas disease in Brazil, 1990-2016: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. International journal for parasitology. 2019 Mar:49(3-4):301-310. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2018.11.008. Epub 2019 Feb 8 [PubMed PMID: 30738925]

Norman FF, López-Vélez R. Chagas disease: comments on the 2018 PAHO Guidelines for diagnosis and management. Journal of travel medicine. 2019 Oct 14:26(7):. pii: taz060. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taz060. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31407784]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGómez-Ochoa SA, Rojas LZ, Echeverría LE, Muka T, Franco OH. Global, Regional, and National Trends of Chagas Disease from 1990 to 2019: Comprehensive Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Global heart. 2022:17(1):59. doi: 10.5334/gh.1150. Epub 2022 Aug 24 [PubMed PMID: 36051318]

Gomez M, Matamoros WA, Larre-Campuzano S, Yépez-Mulia L, De Fuentes-Vicente JA, Hoagstrom CW. Revised New World bioregions and environmental correlates for vectors of Chagas disease (Hemiptera, Triatominae). Acta tropica. 2024 Jan:249():107063. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2023.107063. Epub 2023 Nov 8 [PubMed PMID: 37944838]

Bern C, Montgomery SP, Katz L, Caglioti S, Stramer SL. Chagas disease and the US blood supply. Current opinion in infectious diseases. 2008 Oct:21(5):476-82. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32830ef5b6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18725796]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCurtis-Robles R, Auckland LD, Snowden KF, Hamer GL, Hamer SA. Analysis of over 1500 triatomine vectors from across the US, predominantly Texas, for Trypanosoma cruzi infection and discrete typing units. Infection, genetics and evolution : journal of molecular epidemiology and evolutionary genetics in infectious diseases. 2018 Mar:58():171-180. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.12.016. Epub 2017 Dec 18 [PubMed PMID: 29269323]

Eggers P, Offutt-Powell TN, Lopez K, Montgomery SP, Lawrence GG. Notes from the Field: Identification of a Triatoma sanguisuga "Kissing Bug" - Delaware, 2018. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2019 Apr 19:68(15):359. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6815a5. Epub 2019 Apr 19 [PubMed PMID: 30998670]

Garcia MN, Hernandez D, Gorchakov R, Murray KO, Hotez PJ. The 1899 United States Kissing Bug Epidemic. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2015 Dec:9(12):e0004117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004117. Epub 2015 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 26719888]

Traina M, Meymandi S, Bradfield JS. Heart Failure Secondary to Chagas Disease: an Emerging Problem in Non-endemic Areas. Current heart failure reports. 2016 Dec:13(6):295-301 [PubMed PMID: 27807757]

Martín-Escolano J, Marín C, Rosales MJ, Tsaousis AD, Medina-Carmona E, Martín-Escolano R. An Updated View of the Trypanosoma cruzi Life Cycle: Intervention Points for an Effective Treatment. ACS infectious diseases. 2022 Jun 10:8(6):1107-1115. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.2c00123. Epub 2022 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 35652513]

Bonney KM, Luthringer DJ, Kim SA, Garg NJ, Engman DM. Pathology and Pathogenesis of Chagas Heart Disease. Annual review of pathology. 2019 Jan 24:14():421-447. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020117-043711. Epub 2018 Oct 24 [PubMed PMID: 30355152]

Nunes MCP, Beaton A, Acquatella H, Bern C, Bolger AF, Echeverría LE, Dutra WO, Gascon J, Morillo CA, Oliveira-Filho J, Ribeiro ALP, Marin-Neto JA, American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Stroke Council. Chagas Cardiomyopathy: An Update of Current Clinical Knowledge and Management: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018 Sep 18:138(12):e169-e209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000599. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30354432]

Bern C. Chagas disease in the immunosuppressed host. Current opinion in infectious diseases. 2012 Aug:25(4):450-7. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328354f179. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22614520]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePinazo MJ, Espinosa G, Cortes-Lletget C, Posada Ede J, Aldasoro E, Oliveira I, Muñoz J, Gállego M, Gascon J. Immunosuppression and Chagas disease: a management challenge. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2013:7(1):e1965. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001965. Epub 2013 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 23349998]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBern C, Messenger LA, Whitman JD, Maguire JH. Chagas Disease in the United States: a Public Health Approach. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2019 Dec 18:33(1):. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00023-19. Epub 2019 Nov 27 [PubMed PMID: 31776135]

Bern C, Martin DL, Gilman RH. Acute and congenital Chagas disease. Advances in parasitology. 2011:75():19-47. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385863-4.00002-2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21820550]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRincón-Acevedo CY, Parada-García AS, Olivera MJ, Torres-Torres F, Zuleta-Dueñas LP, Hernández C, Ramírez JD. Clinical and Epidemiological Characterization of Acute Chagas Disease in Casanare, Eastern Colombia, 2012-2020. Frontiers in medicine. 2021:8():681635. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.681635. Epub 2021 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 34368188]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBeucler N, Torrico F, Hibbert D. A tribute to Cecilio Romaña: Romaña's sign in Chagas disease. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2020 Nov:14(11):e0008836. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008836. Epub 2020 Nov 12 [PubMed PMID: 33180778]

Klotz JH, Dorn PL, Logan JL, Stevens L, Pinnas JL, Schmidt JO, Klotz SA. "Kissing bugs": potential disease vectors and cause of anaphylaxis. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2010 Jun 15:50(12):1629-34. doi: 10.1086/652769. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20462351]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAnderson C, Belnap C. The Kiss of Death: A Rare Case of Anaphylaxis to the Bite of the "Red Margined Kissing Bug". Hawai'i journal of medicine & public health : a journal of Asia Pacific Medicine & Public Health. 2015 Sep:74(9 Suppl 2):33-5 [PubMed PMID: 26793414]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVieira JL, Távora FRF, Sobral MGV, Vasconcelos GG, Almeida GPL, Fernandes JR, da Escóssia Marinho LL, de Mendonça Trompieri DF, De Souza Neto JD, Mejia JAC. Chagas Cardiomyopathy in Latin America Review. Current cardiology reports. 2019 Feb 12:21(2):8. doi: 10.1007/s11886-019-1095-y. Epub 2019 Feb 12 [PubMed PMID: 30747287]

ROSENBAUM MB. CHAGASIC MYOCARDIOPATHY. Progress in cardiovascular diseases. 1964 Nov:7():199-225 [PubMed PMID: 14223289]

OKUMURA M, NETTO AC. [ETIOPATHOGENESIS OF CHAGAS' MEGACOLON. EXPERIMENTAL CONTRIBUTION]. Revista do Hospital das Clinicas. 1963 Sep-Oct:18():351-60 [PubMed PMID: 14113332]

KOEBERLE F. ENTEROMEGALY AND CARDIOMEGALY IN CHAGAS DISEASE. Gut. 1963 Dec:4(4):399-405 [PubMed PMID: 14084752]

Köberle F. Chagas' disease and Chagas' syndromes: the pathology of American trypanosomiasis. Advances in parasitology. 1968:6():63-116 [PubMed PMID: 4239747]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAcquatella H. Echocardiography in Chagas heart disease. Circulation. 2007 Mar 6:115(9):1124-31 [PubMed PMID: 17339570]

Santos É, Menezes Falcão L. Chagas cardiomyopathy and heart failure: From epidemiology to treatment. Revista portuguesa de cardiologia. 2020 May:39(5):279-289. doi: 10.1016/j.repc.2019.12.006. Epub 2020 Jun 10 [PubMed PMID: 32532535]

Rojas LZ, Glisic M, Pletsch-Borba L, Echeverría LE, Bramer WM, Bano A, Stringa N, Zaciragic A, Kraja B, Asllanaj E, Chowdhury R, Morillo CA, Rueda-Ochoa OL, Franco OH, Muka T. Electrocardiographic abnormalities in Chagas disease in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2018 Jun:12(6):e0006567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006567. Epub 2018 Jun 13 [PubMed PMID: 29897909]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDíaz Alcázar MDM, Zúñiga de Mora Figueroa B, García Robles A. Megacolon with infectious etiology that is infrequent in our country: Chagas disease. Revista espanola de enfermedades digestivas. 2020 May:112(5):423-424. doi: 10.17235/reed.2020.6643/2019. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32338024]

Mayta H, Romero YK, Pando A, Verastegui M, Tinajeros F, Bozo R, Henderson-Frost J, Colanzi R, Flores J, Lerner R, Bern C, Gilman RH, Chagas Working Group in Perú and Bolivia. Improved DNA extraction technique from clot for the diagnosis of Chagas disease. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2019 Jan:13(1):e0007024. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007024. Epub 2019 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 30633743]

Caroli AP, Mansoldo FRP, Cardoso VS, Lage CLS, Carmo FL, Supuran CT, Beatriz Vermelho A. Are patents important indicators of innovation for Chagas disease treatment? Expert opinion on therapeutic patents. 2023 Mar:33(3):193-209. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2023.2176219. Epub 2023 Feb 15 [PubMed PMID: 36786067]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBenck L, Kransdorf E, Patel J. Diagnosis and Management of Chagas Cardiomyopathy in the United States. Current cardiology reports. 2018 Oct 11:20(12):131. doi: 10.1007/s11886-018-1077-5. Epub 2018 Oct 11 [PubMed PMID: 30311008]

Morillo CA, Marin-Neto JA, Avezum A, Sosa-Estani S, Rassi A Jr, Rosas F, Villena E, Quiroz R, Bonilla R, Britto C, Guhl F, Velazquez E, Bonilla L, Meeks B, Rao-Melacini P, Pogue J, Mattos A, Lazdins J, Rassi A, Connolly SJ, Yusuf S, BENEFIT Investigators. Randomized Trial of Benznidazole for Chronic Chagas' Cardiomyopathy. The New England journal of medicine. 2015 Oct:373(14):1295-306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507574. Epub 2015 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 26323937]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRassi A Jr, Marin JA Neto, Rassi A. Chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy: a review of the main pathogenic mechanisms and the efficacy of aetiological treatment following the BENznidazole Evaluation for Interrupting Trypanosomiasis (BENEFIT) trial. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2017 Mar:112(3):224-235. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760160334. Epub 2017 Feb 16 [PubMed PMID: 28225900]

Santos ES, Silva DKC, Dos Reis BPZC, Barreto BC, Cardoso CMA, Ribeiro Dos Santos R, Meira CS, Soares MBP. Immunomodulation for the Treatment of Chronic Chagas Disease Cardiomyopathy: A New Approach to an Old Enemy. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology. 2021:11():765879. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.765879. Epub 2021 Nov 12 [PubMed PMID: 34869068]

Lannes-Vieira J. Multi-therapeutic strategy targeting parasite and inflammation-related alterations to improve prognosis of chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy: a hypothesis-based approach. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2022:117():e220019. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760220019. Epub 2022 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 35320825]

Gray EB, La Hoz RM, Green JS, Vikram HR, Benedict T, Rivera H, Montgomery SP. Reactivation of Chagas disease among heart transplant recipients in the United States, 2012-2016. Transplant infectious disease : an official journal of the Transplantation Society. 2018 Dec:20(6):e12996. doi: 10.1111/tid.12996. Epub 2018 Oct 2 [PubMed PMID: 30204269]

Teixeira FV, Netinho JG. Surgical treatment of chagasic megacolon: Duhamel-Haddad procedure is also a good option. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2003 Nov:46(11):1576; author reply 1577-8 [PubMed PMID: 14605585]

Di Martino C, Nesi G, Tonelli F. Surgical treatment of chagasic megacolon with Duhamel-Habr-Gama technique modulated by frozen-section examination. Surgical infections. 2014 Aug:15(4):454-7. doi: 10.1089/sur.2012.181. Epub 2014 May 13 [PubMed PMID: 24824159]

Espin-Basany E, Vallribera-Valls F, Lopez-Cano M, Lozoya-Trujillo R, Sánchez-Garcia JL, Armengol-Carrasco M. Multimedia article. Laparoscopic-assisted rectosigmoidectomy with ileal loop interposition. Surgical treatment of chagasic megacolon. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2008 Sep:51(9):1421. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9275-7. Epub 2008 Jun 7 [PubMed PMID: 18536972]

Netinho JG, Cunrath GS, Ronchi LS. Rectosigmoidectomy with ileal loop interposition: a new surgical method for the treatment of chagasic megacolon. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2002 Oct:45(10):1387-92 [PubMed PMID: 12394440]

Bastos CJ, Aras R, Mota G, Reis F, Dias JP, de Jesus RS, Freire MS, de Araújo EG, Prazeres J, Grassi MF. Clinical outcomes of thirteen patients with acute chagas disease acquired through oral transmission from two urban outbreaks in northeastern Brazil. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2010 Jun 15:4(6):e711. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000711. Epub 2010 Jun 15 [PubMed PMID: 20559542]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTorres RM, Correia D, Nunes MDCP, Dutra WO, Talvani A, Sousa AS, Mendes FSNS, Scanavacca MI, Pisani C, Moreira MDCV, de Souza DDSM, de Oliveira Junior W, Martins SM, Dias JCP. Prognosis of chronic Chagas heart disease and other pending clinical challenges. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2022:117():e210172. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760210172. Epub 2022 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 35674528]

Edwards MS, Stimpert KK, Montgomery SP. Addressing the Challenges of Chagas Disease: An Emerging Health Concern in the United States. Infectious diseases in clinical practice (Baltimore, Md.). 2017 May:25(3):118-125. doi: 10.1097/ipc.0000000000000512. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37200690]

Bern C. Antitrypanosomal therapy for chronic Chagas' disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2011 Jun 30:364(26):2527-34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct1014204. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21714649]

Mills RM. Chagas Disease: Epidemiology and Barriers to Treatment. The American journal of medicine. 2020 Nov:133(11):1262-1265. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.05.022. Epub 2020 Jun 24 [PubMed PMID: 32592664]