Introduction

The hip joint is primarily responsible for providing dynamic support of the weight of the upper body while facilitating force and load transmission from the axial skeleton to the lower extremities. This structure and function allow for ambulation and mobility. It is a ball-and-socket synovial joint that articulates the head of the femur with the acetabulum of the pelvis.

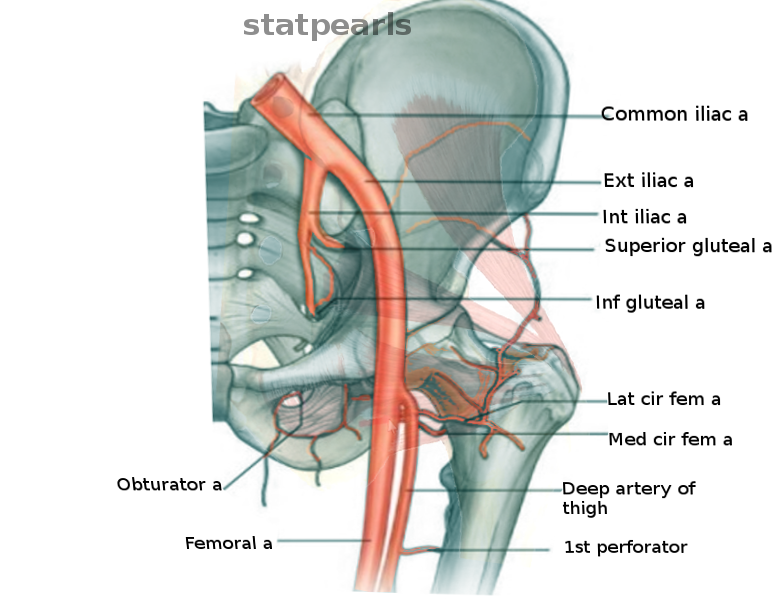

The arteries of the pelvic region originate from the bifurcation of the common iliac artery into the external iliac artery and the internal iliac artery. The internal iliac artery divides into anterior and posterior trunks at the superior border of the greater sciatic foramen. Various branches of these major vessels supply the hip joint.[1]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The hip joint is the connection that exists between the lower extremity and the axial skeleton. Its deep ball-and-socket construction allows for significant levels of stability, load transmission, and weight bearing while still being able to facilitate movement in three planes: flexion/extension, abduction/adduction, and internal/external rotation.[2][3]

Embryology

The hip joint is formed predominantly from mesoderm and begins to come into existence between weeks 4 to 6 gestational age. During week 7, cartilage precursor cells start to form the bony components of the hip joint: the acetabulum and the head of the femur. Hip joint development is mostly complete by the eleventh week of gestation.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The arterial blood supply of the hip joint is complex and comes from multiple sources.

The following list includes the branches of the anterior trunk of the internal iliac artery:

- Obturator artery

- Umbilical artery, which branches to form the superior vesical artery

- Inferior vesical artery

- Vaginal artery (female)

- Uterine artery (female)

- Middle rectal artery

- Internal pudendal artery

- Inferior gluteal artery

The following list includes the branches of the posterior trunk of the internal iliac artery:

- Superior gluteal artery

- Lateral sacral arteries

- Iliolumbar artery

Most of the arteries of the hip region originate from the external iliac artery and include:

- Femoral artery

- Superficial circumflex iliac artery

- External pudendal artery

- Superficial femoral artery

- Profunda femoral artery (the deep artery of the thigh)

- Lateral femoral circumflex artery

- Medial femoral circumflex artery

The capsular blood supply receives contributions from four key vessels: the medial and lateral circumflex femoral arteries (MFCA and LFCA, respectively), which are branches of the profunda femoris artery, as well as the superior gluteal artery (SGA), a branch of the posterior division of the internal iliac artery, and the inferior gluteal artery (IGA), a branch of the anterior trunk of the internal iliac artery. In a study of 20 cadaveric hips, Kalhor et al. found that the MFCA and LFCA give off branches that supply the distal and proximal capsule, while the IGA and SGA were the main arterial supply to the posterior capsule.[4][5][6]

There are two significant anastomoses formed by combinations of these arteries. The first is the cruciate anastomosis, a circulatory anastomosis in the upper thigh comprised of the IGA, the MFCA and LFCA, and the first penetrating artery of the profunda femoris. The cruciate anastomosis allows blood to reach the popliteal artery indirectly from the internal iliac artery and IGA if there is an interruption of flow between the external iliac and the femoral arteries. The second major anastomosis is the trochanteric anastomosis which arises from circumferential connections involving the SGA and the MFCA and LFCA around the femoral neck. This anastomosis ensures that the femoral head has multiple alternate sources of blood flow if one or more arteries are injured or occluded.

The obturator artery also provides an important source of arterial blood flow to the hip via the artery of the ligamentum teres. This artery penetrates the hip joint through the acetabular notch and traverses inside the ligament of the head of the femur to send blood to the femoral head. This blood supply is mostly insignificant in adults relative to the vessels mentioned above, but in the pediatric population, it is a crucial component as the cartilage-composed epiphyseal line does not allow for substantial blood flow to the head of the femur. Thus, the artery of the ligamentum teres helps supply the head and neck of the femur on its own until the growth plate closes. Around 15 years of age, this branch loses patency and becomes a remnant in the adult hip, explaining why it does not prevent avascular necrosis in fractures of the femoral neck.[7]

The lymphatic drainage from the anterior side of the hip drains to the deep inguinal nodes, while the posterior and medial aspects drain alongside the gluteal and obturator arteries respectively to the internal iliac nodes.

Nerves

Innervation of the hip joint primarily derives from the femoral, obturator, genitofemoral, sciatic, superior gluteal, lateral femoral cutaneous, and posterior femoral cutaneous nerves.[2]

Muscles

There are many muscles involved in the movement of the hip joint, these include (in alphabetical order) the:

- Adductor longus, brevis, and magnus

- Gluteus maximus, medius, and minimus

- Gracilis

- Hamstring muscles: semimembranosus, semitendinosus, and the biceps femoris

- Iliacus

- Obturator

- Pectineus

- Piriformis

- Psoas major

- Quadriceps muscles: rectus femoris, vastus intermedius, vastus lateralis, and vastus medialis

- Quadratus femoris

- Sartorius

- Tensor fascia latae

The blood supply to these muscles derives from the same major vessels that supply the hip joint. The MFCA supplies the adductor group, gracilis, and pectineus. The LFCA supplies the vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius, and rectus femoris. The vastus medialis gets its blood supply from the superficial femoral artery as well as the deep femoral artery. The perforating arteries of the profunda femoris give vascular supply to the hamstring muscles.

Physiologic Variants

The most common and most clinically significant source of variation in the location of hip arteries is with the MFCA and its point of origin. According to Al-Talalwah, in 342 dissected hemipelvis specimens the MFCA arose from the common and deep femoral artery in 39.3% and 57% of cases, respectively. In 2.5% of cases, it originated from the superficial femoral artery and in 0.6% of cases it arose from the LFCA. Due to this variation, it is highly important that surgeons keep in mind all possibilities to avoid iatrogenic injury of the MFCA that can lead to avascular necrosis of the femoral head.[8]

Surgical Considerations

As with all surgeries, various complications must be kept in mind to avoid intraoperative and postoperative issues. These include bleeding (usually from the MFCA during total hip arthroplasty procedures),[9] not maintaining adequate blood flow to nearby vessels during procedures on the hip,[10][11] or even avulsion injuries to the profundal femoris artery that may lead to pseudoaneurysms. These possible complications are reasons why it is of utmost importance to assess for neurovascular injuries immediately after hip operations and regularly during postoperative follow-up evaluations. Overall, though, vascular injuries are fortunately extremely rare complications of hip procedures.[12]

Clinical Significance

Avascular necrosis of the hip is a condition characterized by the death of the femoral head due to disruption of its vascular supply, chiefly the MFCA. This condition results in the insidious onset of hip pain, usually with movement, and can be the result of a variety of factors. Some of the most common causes can be remembered by the mnemonic “ASEPTIC”:

- Alcohol/AIDS

- Steroids, sickle cell disease, SLE

- Erlenmeyer flask (Gaucher disease)

- Pancreatitis

- Trauma

- Idiopathic (Legg-Calve-Perthes disease), infection, iatrogenic

- Caisson disease

Making the diagnosis is dependent on a good history and physical along with imaging. Hip radiographs may be negative early in the course of the disease so if there is a high clinical suspicion then an MRI may be utilized.[13][14]

Media

References

Gold M, Munjal A, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Hip Joint. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29262200]

Glenister R, Sharma S. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Hip. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30252275]

Bordoni B, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Thigh Quadriceps Muscle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30020706]

Kuhns BD, Weber AE, Levy DM, Bedi A, Mather RC 3rd, Salata MJ, Nho SJ. Capsular Management in Hip Arthroscopy: An Anatomic, Biomechanical, and Technical Review. Frontiers in surgery. 2016:3():13. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2016.00013. Epub 2016 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 26973840]

Kalhor M, Beck M, Huff TW, Ganz R. Capsular and pericapsular contributions to acetabular and femoral head perfusion. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2009 Feb:91(2):409-18. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01679. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19181985]

McCormick F, Kleweno CP, Kim YJ, Martin SD. Vascular safe zones in hip arthroscopy. The American journal of sports medicine. 2011 Jul:39 Suppl():64S-71S. doi: 10.1177/0363546511414016. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21709034]

Perumal V, Woodley SJ, Nicholson HD. Neurovascular structures of the ligament of the head of femur. Journal of anatomy. 2019 Jun:234(6):778-786. doi: 10.1111/joa.12979. Epub 2019 Mar 18 [PubMed PMID: 30882902]

Al-Talalwah W. The medial circumflex femoral artery origin variability and its radiological and surgical intervention significance. SpringerPlus. 2015:4():149. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-0881-2. Epub 2015 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 25883882]

Chiron P, Murgier J, Reina N. Reduced blood loss with ligation of medial circumflex pedicle during total hip arthroplasty with minimally invasive posterior approach. Orthopaedics & traumatology, surgery & research : OTSR. 2014 Apr:100(2):237-8. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2013.11.013. Epub 2014 Feb 20 [PubMed PMID: 24559883]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceStryker LS, Gilliland JM, Odum SM, Mason JB. Femoral Vessel Blood Flow Is Preserved Throughout Direct Anterior Total Hip Arthroplasty. The Journal of arthroplasty. 2015 Jun:30(6):998-1001. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.01.012. Epub 2015 Jan 21 [PubMed PMID: 25662670]

Grob K, Monahan R, Gilbey H, Yap F, Filgueira L, Kuster M. Distal extension of the direct anterior approach to the hip poses risk to neurovascular structures: an anatomical study. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2015 Jan 21:97(2):126-32. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.00551. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25609439]

Huynh S, Kayssi A, Koo K, Rajan D, Safir O, Forbes TL. Avulsion injury to the profunda femoris artery after total hip arthroplasty. Journal of vascular surgery. 2016 Aug:64(2):494-496. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.08.088. Epub 2015 Oct 21 [PubMed PMID: 26482999]

Hsu H, Nallamothu SV. Hip Osteonecrosis. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29763129]

Mills S, Burroughs KE. Legg-Calve-Perthes Disease. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30020602]