Introduction

Rhytidectomy, also known as face lifting, is a surgical procedure aiming to reposition facial soft tissues to achieve a more youthful and harmonious appearance. Now a common procedure, it was relatively unknown in the early 20th century because of negative public perceptions towards cosmetic surgery and secrecy among surgeons regarding their techniques.[1] The first documented facelift was performed in 1901 by Eugene von Holländer, which involved excision and reapproximation of excess skin with minimal undermining. After World War I ended in 1918, the demand for reconstructive surgeries increased, and so did the Western cultural acceptance of plastic surgery as a whole. However, it was not until after World War II, with the advent of antibiotics and the evolution of anesthesia, that a more aggressive approach to face lifting became practical.

In 1969, Swedish plastic surgeon Tord Skoog was the first to report a facelift procedure by dissecting along the superficial fascia of the face, leading to a longer-lasting rejuvenation. This fascia was later termed the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) in an anatomical study by Mitz and Peyronie in 1976, which ultimately led to the development of the surgical technique now known as "SMAS rhytidectomy." [2] This approach involves either plication or imbrication of the SMAS, the former consisting of folding and suspending the SMAS, while the latter involves excision of excess SMAS and closure of the gap with overlapping of the cut edges and suspension of the fascia.

The "tri-plane rhytidecomy" was introduced by Hamra in 1983 to include subcutaneous elevation of cervical skin to improve neck contouring. These approaches, however, do not address the melolabial fold or laxity of midface soft tissues. In 1990, Hamra introduced "deep-plane rhytidectomy" to further dissect zygomaticus musculature and ligaments to reposition the malar fat pad and hence efface the melolabial fold (MLF). In 1991, Hamra further modified his technique into the "composite rhytidecomy" to include the orbicularis oculi muscle in the dissection to improve the eyelid and cheek profile, allowing repositioning of the suborbicularis oculi fat (SOOF) to correct hollowing of the orbits from previous facelift procedures.[3] Today, there are myriad variations of facelift techniques designed to address patient-specific priorities, from jowls to melolabial folds, platysmal banding, and length of the scar.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Facial aging is due to the gravitational effect on soft tissues, the weakening of suspensory ligaments, and skin laxity, lipoatrophy, and bony resorption. This process results in the classic appearance of hollowing in the temporal, infracomissural, pre-jowl, and cheek areas. Sagging facial fat pads and surrounding anchoring ligaments deepen the MLFs, pre-jowl sulci, and nasojugal folds. Preferential bony resorption in the maxilla and periorbital bones also accentuates the palpebral-malar groove and causes sagging of lower eyelid soft tissues. Jowl formation from the descent of the buccal fat pad distorts the jawline and is a common reason for people to seek rhytidectomy. Jowls can often be addressed with SMAS rhytidectomy alone; however, if midface structures such as nasojugal folds or MLFs require rejuvenation, a deep-plane or composite rhytidectomy may be more appropriate.

A thorough understanding of anatomy, in particular the relationship of fascial planes to one another, is critical to the success of any surgery and the avoidance of complications. This is especially true in the face, where important structures are in close proximity, and damage may alter a patient's aesthetic appearance in a way that is not easily hidden or reversed. The elucidation of the SMAS, in particular, has had a huge impact on rhytidectomy, affecting both the current understanding of the facial aging process and the evolution of techniques to combat it. The SMAS is a fibrofatty layer of soft tissue overlying the parotid gland in the lateral face and investing the muscles of facial expression medially. It is contiguous with the platysma inferiorly, the temporoparietal fascia (TPF) or superficial temporal fascia superior to the zygomatic arch, and the SMAS attaches to the deep investing fascia of SCM posteriorly.[4]

Another major consideration in any facial surgery is the location of the facial nerve. The facial nerve exits the temporal bone of the skull via the stylomastoid foramen and travels through the parenchyma of the parotid gland, where it divides into its main branches at the pes anserinus, so-called because its branching appearance resembles that of a goose's foot. The facial nerve branches are classified into five major divisions: frontal/temporal, zygomatic, buccal, marginal mandibular, and cervical, although several different branching patterns have been described.[5] The nerve runs deep to the SMAS and its contiguous layers and innervates the mimetic muscles from their deep surfaces except the levator anguli oris, buccinator, and mentalis muscles. During rhytidectomy, the frontal and marginal mandibular branches are the most commonly injured motor nerves, although the great auricular nerve (GAN) is still more frequently injured.[6][7]

Cervicoplasty, or neck lift, is often performed at the same time as face lifting to achieve a balanced, rejuvenated appearance. The Dedo classification of the aging neck is often used to assess the condition of the skin, submental adipose tissue, platysma, and bone positioning.[8] The goal of cervical rhytidectomy is to restore a youthful contour with a cervicomental angle of 90 to 105 degrees and often to reduce excess submental fat and/or reduce the appearance of vertical platysmal bands.

Surgical Landmarks and Considerations

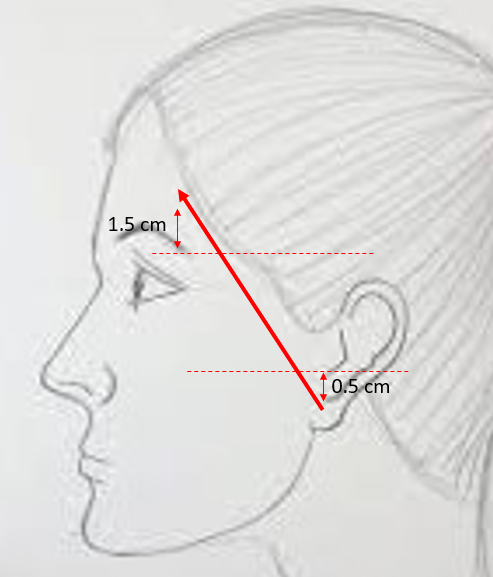

- Pitanguy's line Approximates the course of the frontal branch of the facial nerve: a line drawn from a point 0.5 cm below the tragus to a point 1.5 cm superior to the lateral brow. The nerve travels deep to the TPF and superficial to the superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia (see Image. Course of the Temporal Branch).[9]

- McKinney's point: Identifies the location of the GAN: 1/3 of the distance from the mastoid tip to the clavicular head of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM). The GAN can be consistently found at this location at the posterior border of SCM before branching into anterior and posterior segments. The external jugular vein can also be found consistently 1 cm anterior to this location, parallel to the nerve.[7]

- Transverse facial artery: A branch of the superficial temporal artery can be consistently found 2.5 cm lateral and 3 cm inferior to the lateral canthus. Injury to this vessel may contribute to necrosis of skin flaps and delayed healing. Usually, the buccal branches of the facial nerve are superior and inferior to this vessel, and Stensen's duct from the parotid gland lies inferior to it but in the same fascial plane.

- Zuker's point: Used to identify the motor branch to the zygomaticus major muscle: midway along a line between the root of the helix and the oral commissure, and the nerve that crosses this point is typically the branch lying superior to the transverse facial artery(see Image. Course of the Facial Nerve).[10]

- Facial nerve arborization: In general, injuries to the facial nerve medial to a vertical line through the lateral canthus may be less apparent due to redundancy and anastomoses of buccal and zygomatic branches in the midface and do not generally warrant nerve exploration or repair.

- Marginal mandibular nerve: Located superficially to the facial vessels, often closely associated with or wrapping around the facial vein. Posterior to the gonial notch of the mandible, this nerve can be found below the inferior margin of the mandible in 20% of patients and above it in 80%. Anterior to the gonial notch, the marginal mandibular nerve runs superior to the lower edge of the jaw in nearly all patients.[11]

- Cervical branch of the facial nerve: Located 1 cm below the midpoint of a line running between the mentum and the tip of the mastoid process, the cervical branch innervates the platysma muscle as well as the depressor labii inferioris muscle.[12] Injury to this nerve will cause lower lip asymmetry, with the affected side unable to depress the bottom lip during smiling.

Indications

Rhytidectomy is only one of many treatment modalities available to the aging face patient, repositioning soft tissue that has descended over time and reducing the amount of excess skin present. The type of facelift performed will be based on the patient’s aesthetic concerns and individual anatomy. A thorough assessment of skin quality, rhytids, scars, fat descent and atrophy, and skeletal resorption must be performed during the pre-operative consultation to establish realistic expectations for surgical outcomes. Facial analysis and photography (frontal, lateral, oblique, and base view) with special attention to facial asymmetries, contour irregularities, and hairlines must be documented to ensure the patient and surgeon share expectations.

Patients primarily concerned with jowls or neck sagging with or without platysmal banding may be offered SMAS rhytidectomy and cervicoplasty. If deep MLFs or significant malar fat descent are present, a deep-plane rhytidectomy or adjunctive mid-face lift is indicated. Composite rhytidectomy, which involves a deep-plane approach with additional repositioning of the SOOF, is indicated to further improve the lid-cheek junction.

Additionally, various rhytidectomy techniques can be combined with adjuvant therapies such as brow lift, blepharoplasty, cervicoplasty, subcutaneous fillers or fat transfer, and laser resurfacing to manage the aging face holistically with a multi-modality treatment approach.

Contraindications

Major medical comorbidities such as diabetes, immunocompromise, steroid requirements, bleeding diatheses, and connective tissue disorders can impede wound healing. Smoking is also a major risk factor for skin flap necrosis because of its adverse impact on perfusion; radiation therapy can have a similar effect, and operating aggressively on these patients should be avoided.[13][14] It is recommended that smoking cessation take place at least 2 to 4 weeks prior to surgery and be maintained for a month after surgery to allow optimal healing.

In some cases, a history of severe sun exposure with multiple burns can also predispose patients to wound-healing difficulties. Bleeding diatheses, requirements for blood thinners, and uncontrolled hypertension can be particularly problematic because they raise the risk of hematoma formation, which is already one of the more common complications after rhytidectomy. The use of medications and herbal supplements with anticoagulation properties should also be stopped, if possible, two weeks prior to surgery. Pre-operative assessment of any psychiatric history is essential in order to determine the patient’s motivation in seeking surgery. Patients with body dysmorphic disorder should be evaluated by qualified mental health professionals before considering surgery. Additionally, any significant comorbidities that can be mitigated preoperatively should be addressed before undertaking cosmetic procedures; patients who are poor candidates for surgery, in general, should not be offered rhytidectomy.

Equipment

A standard rhytidectomy instrument set should include, at a minimum:

- Facelift scissors, such as Gorney-Freeman, Kaye, Goldman-Fox, and Castañares scissors

- Suture scissors, such as Mayo and iris or tenotomy scissors

- Needle drivers, such as Halsey or Webster; Haney needle drivers may be useful for platysmaplasty, and some surgeons prefer Castroviejo needle drivers for fine suturing

- Forceps, such as Adson-Brown, DeBakey, Gerald, or fine Castroviejo forceps

- #15 blade scalpel and #3 handle

- Ferreira facelift or breast retractor, with or without a light carrier

- Headlight if there is no light carrier on the retractor

- Joseph or Freeman skin hooks

- Suction

- Bipolar and/or monopolar electrocautery

Sutures may include:

- 2-0 polydioxanone, braided polyester, or polyglactin for suspension of the SMAS and platysma

- 4-0 or 5-0 polyglactin or poliglecaprone for deep dermal closure

- 5-0 or 6-0 polypropylene, nylon, or gut for skin closure

- Staples for the portion of the postauricular incision within the hairline

Some surgeons may place drains and a pressure dressing with ice packs; others may avoid drains and consider using a fibrin tissue sealant to reduce dead space under the facial flaps. If other procedures, such as blepharoplasty, brow lift, fat transfer, or laser resurfacing, are to be undertaken during the same anesthetic, additional equipment will be required.

Personnel

As for most surgical procedures, a surgical technologist and a circulating nurse are required. In most cases, rhytidectomy is performed under general anesthesia, which requires an anesthesia provider. An assistant to the surgeon will also make the procedure more efficient.

Preparation

The patient is positioned supine on the operating table, and if the patient is intubated, suturing the endotracheal tube to one of the central maxillary incisors may help to keep the airway secure while permitting sufficient access to both sides of the face and neck. Povidone iodine or isopropyl alcohol may be used for skin preparation. Many surgeons will also inject significant amounts of local anesthetic or tumescent solution with a dilute local anesthetic before and during the operation to minimize anesthetic drug requirements and maximize hemostasis to prevent postoperative bruising. The tumescent solution typically contains 500 to 1,000 mg of lidocaine, 0.5-1 mg of epinephrine, and 10-12.5 mEq of sodium bicarbonate diluted in 1 L of normal saline. Intravenous antibiotics, steroids, and tranexamic acid may be administered as well.

Technique or Treatment

Preparation

- Marking incisions: the exact incision pattern will vary from surgeon to surgeon, but a Blair incision will typically start either within or along the inferior border of the temporal hair tuft and approach the root of the helix, at which point it will follow the junction of the auricle and the facial skin towards the tragus. The incision may proceed just medial to the posterior margin of the tragus (post-tragal approach) or within a skin crease anterior to the tragus (pre-tragal approach). The post-tragal approach may hide the scar better but risks winging the tragus laterally postoperatively, while the pre-tragal incision may result in a more apparent scar. Male patients will usually require a pre-tragal approach in order to avoid pulling hair-bearing skin onto the tragus during closure. The incision will then curve around where the lobule meets the cheek, often 1-2 mm onto the cheek skin rather than directly in the sulcus to prevent webbing. From there, the incision proceeds superiorly up the posterior surface of the auricle, approximately 1/3 of the way from the postauricular sulcus to the helical rim; as the scar contracts postoperatively, it will be pulled into the middle of the postauricular sulcus if the incision is placed slightly onto the back of the concha during surgery, as described. The incision should then turn gently 90 degrees to enter the postauricular hairline at the narrowest portion of non-hair-bearing skin behind the ear, typically at the level of Darwin's tubercle. The incision then travels inferiomedially as far as necessary to prevent a standing cutaneous cone during closure.[15][16]

- Some surgeons mark the extent of the skin flap as well

- SMAS rhytidectomy: ~6 cm anterior to the tragus

- Deep-plane rhytidectomy: mark a line between the angle of the mandible and the lateral canthus, where the surgical plane will transition from subdermal to sub-SMAS

- Marking surgical landmarks: some surgeons find it helpful to identify the paths of the frontal, marginal mandibular, and great auricular nerves prior to the incision or to mark the angle of the mandible. Marking the vertical platysmal bands may also be helpful if a platysmaplasty is planned.

1. Cervicofacial liposuction: If needed, liposuction is performed prior to flap elevation; once flaps are elevated, maintaining suction with liposuction cannulae can be very challenging. Cannulae are introduced via stab incisions in the submental crease and inferior to the lobules within the marked rhytidectomy incisions. A 3 mm liposuction cannula is introduced with the ports facing away from the dermis, and gentle outward pressure is provided to tent the skin, thereby avoiding damage to the subcutaneous layer and the subdermal plexus.

2. Incision and flap elevation: With the #15 blade scalpel, the incision is carried down to the subcutaneous layer. A subcutaneous flap is then raised with facelift scissors. The operating room light is directed at the skin surface to aid with transillumination, which will help the surgeon maintain the appropriate and consistent thickness of the flap. Proper counter-tension retraction is critical for this dissection to avoid buttonholing the skin.

3. SMAS rhytidectomy: After the SMAS has been exposed, it can be reduced with either plication or imbrication.

- Plication (folding): The SMAS is not violated in this approach. SupraSMAS adipose tissue is excised from the periauricular region. The SMAS is folded onto itself and sutured in place with multiple superolateral and lateral vectors to achieve natural-appearing resuspension.[17]

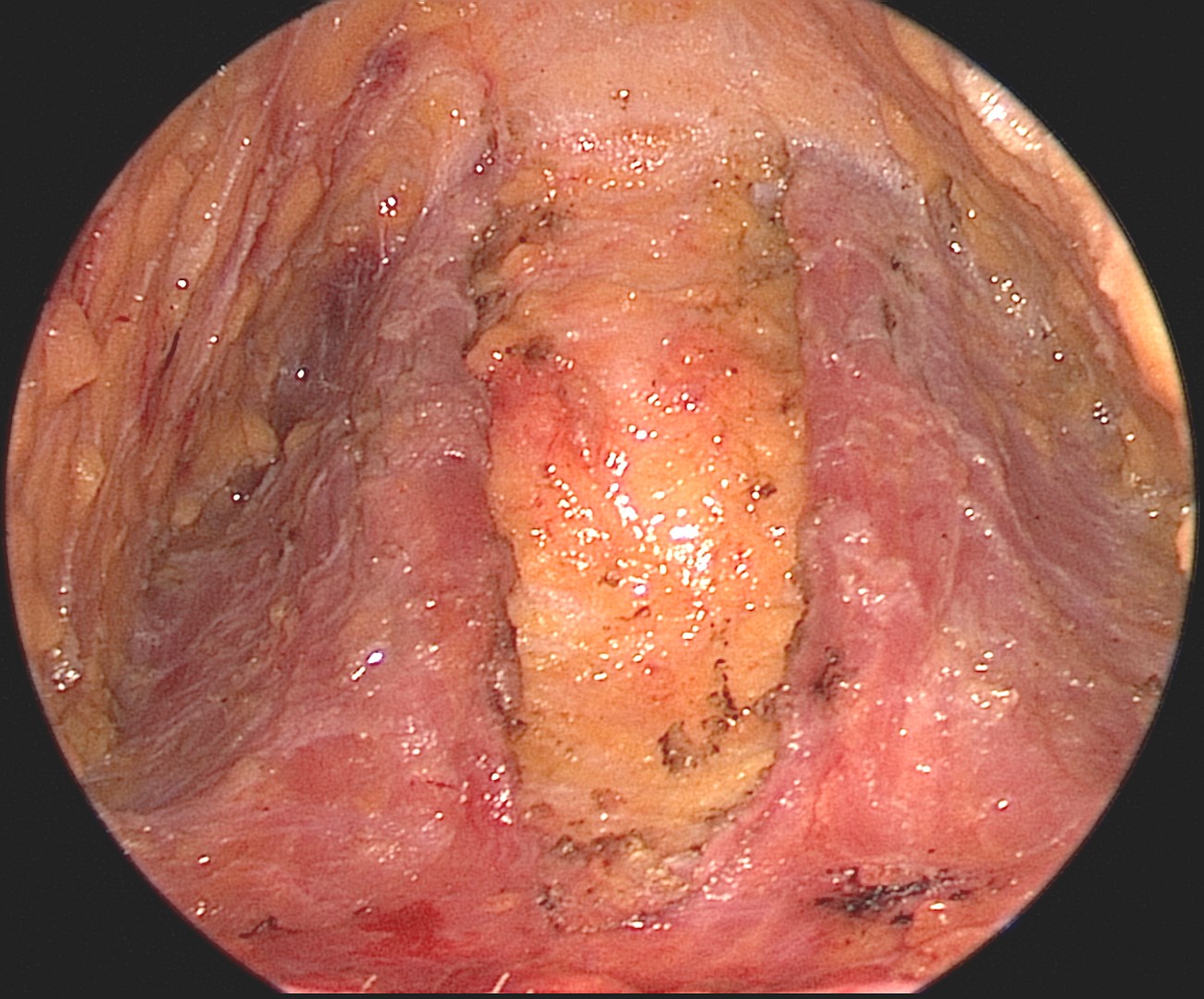

- Imbrication: Involves resection of redundant SMAS. The SMAS is incised 1 cm anterior to the ear in a "J" shape and undermined. The SMAS is then advanced in multiple superolateral vectors from the lobule to the zygomatic arch and sutured in place. If desired, the SMAS incision can be made to create an inferiorly-based flap that is then transposed postauricularly to apply tension along the margin of the mandible and efface the jowls (see Image. Endoscopic View of the Platysma After Suturing).

- Blunt dissection vertically and along the course of the facial nerve is performed in the sub-SMAS plane to avoid damaging the facial nerve. Sutures should only pass through SMAS to avoid injury to the parotid gland deep into the dissection plane.

- The type of suspension sutures used is based on surgeon preference. Either a non-absorbable suture or a large absorbable suture can be used.

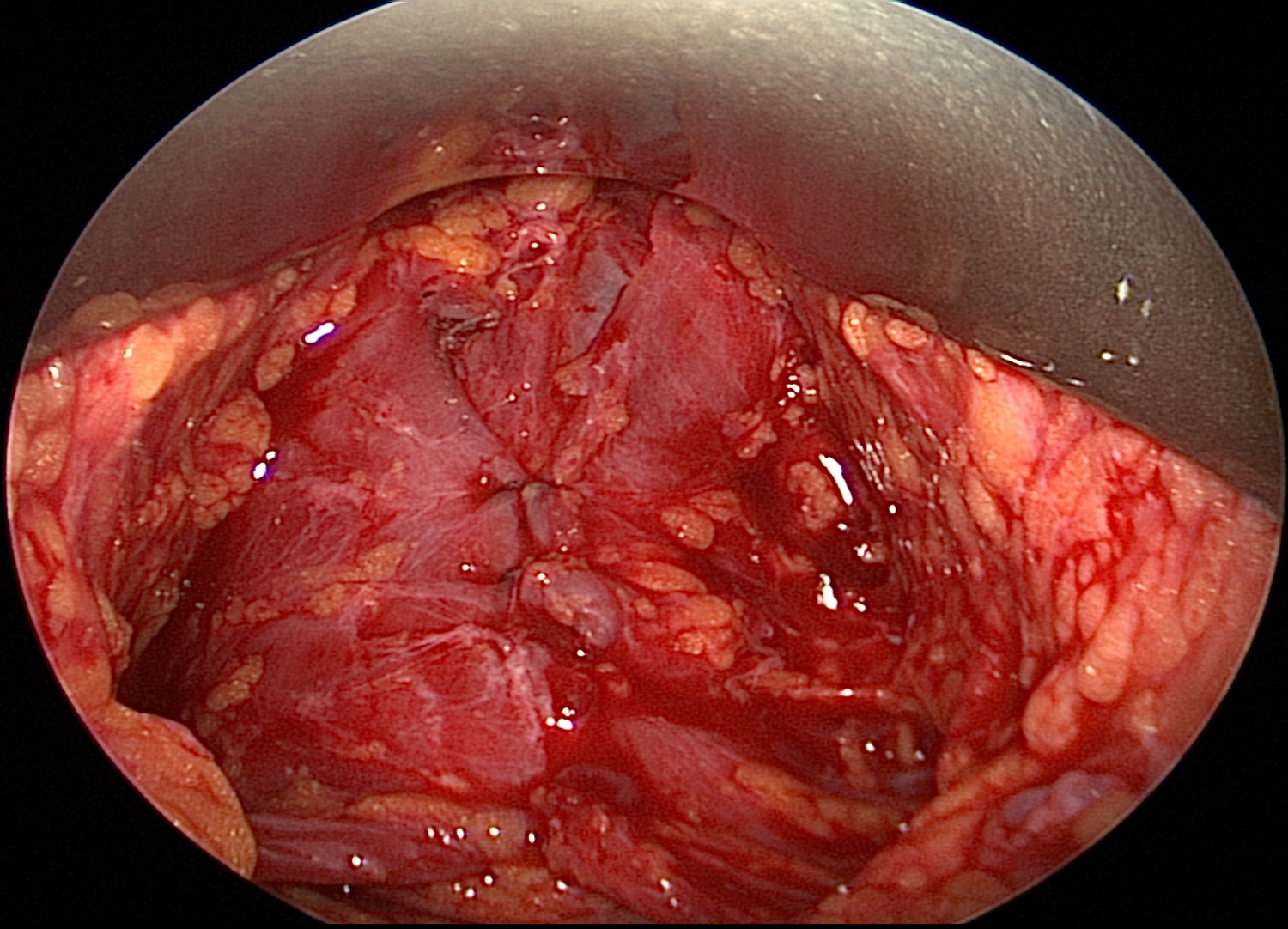

4. Deep Plane rhytidectomy: A similar subdermal skin flap is elevated until the SMAS is incised and the dissection dives deep (see Image. Deep Plane Rhytidectomy).[18]

- An incision is made in the SMAS along a line from the malar eminence to the angle of the mandible. A blunt subSMAS dissection is then carried anteriorly over the parotidomasseteric fascia with its inferior limit at the inferior border of the mandible and the upper limit at the malar eminence. Violation of the parotid should be avoided in order to prevent sialocele and/or first bite syndrome postoperatively.[19]

- The zygomaticus major muscle is identified and dissected on its superficial surface towards the MLF. As a result, the malar fat pad is elevated into the skin flap.

- The flap is suspended posterosuperiorly, taking care to ensure appropriate and symmetric repositioning of the malar fat pads.

5. Minimal Access Cranial Suspension (MACS) lift: As an alternative to aggressive elevation and suspension, subdermal elevation can be performed, and the soft tissue can be elevated with purse-string sutures.[20]

- A thin, vertical loop of 0 polydioxanone suture suspends the SMAS overlying the parotid and the superior aspect of the platysma muscle to the fascia of the temporalis muscle.

- A broad, oblique loop suspends the SMAS above the jowl to the fascia of the temporalis muscle in order to improve mandibular definition.

- The malar loop suspends the malar fat pad to the deep temporal fascia just lateral to the orbit, effacing the MLF.

Hemostasis: This is performed in a meticulous fashion with bipolar cautery. Aggressive cautery can cause facial nerve injury, alopecia, and skin burns, while inadequate control of bleeding vessels may result in hematoma and flap necrosis.

Flap trimming and closure: The skin flap is redraped and secured at 2 to 4 points along the incision using staples or interrupted sutures. Excess skin is then removed, and skin edges closed, taking care not to excise too much skin, which can lead to winging of the tragus, a pixie ear deformity, or scar widening.

- Suture use is based on surgeon preference. Deep dermal sutures are optional. In general, finer sutures (e.g., 6-0) are used to close pre- and post-auricular skin, and the occipital hairline can be closed with skin staples or resorbable sutures.

- Care is taken not to disturb the natural hairline contour.

- Excessive tension on the closure at the inferior border of the lobule can cause a pixie ear deformity.

Platysmaplasty: This may be performed before or after the facial elevation.

- The previous submental liposuction incision is extended to 2 to 4 cm, and a supraplatysmal flap is raised. The medial borders are identified if the platysma is deficient in the midline. Excess fat is then sharply removed, and the platysmal bellies are sutured together in the midline down past the level of the hyoid bone; some surgeons will also divide the platysma transversely at the level of the hyoid to improve the acuity of the cervicomental angle with or without suspension of the cut platysma to the hyoid. Excess skin can be removed prior to closure, as is performed in the facial rhytidectomy portion. If the anterior bellies of the digastric muscles are prominently visible through the skin, they may be debulked, likewise with the submandibular glands, which are often not apparent until the jowls have been effaced.

Dressing: Antibiotic ointment is applied to the incisions, and a compressive dressing is placed to help prevent hematoma formation.

Postoperative care: The patient is seen on postoperative day 1 to remove the dressing and drains, then on day 7 to remove sutures and staples. Cold packs and pain medications are suggested for comfort. Antibiotics beyond the first 24 hours postoperatively are used at the surgeon's discretion. Photographs are taken after three months of healing. The patient should avoid any heavy lifting or strenuous exercise and sleep with the head of the bed elevated. No nose-blowing is permitted.

Complications

As with any procedure, complications may occur in rhytidectomy despite careful preoperative optimization of medical comorbidities and meticulous intraoperative technique. Similar to other aesthetic procedures, the most common adverse outcome is dissatisfaction with the cosmetic result, which can result from a number of issues: scarring, asymmetry, contour irregularities, over/underdone appearance, and others. Building a strong rapport with the patient prior to operating will help the surgeon guide the patient through any postoperative challenges that occur postoperatively and may not only improve patient satisfaction but also decrease the likelihood of litigation should a suboptimal result occur.

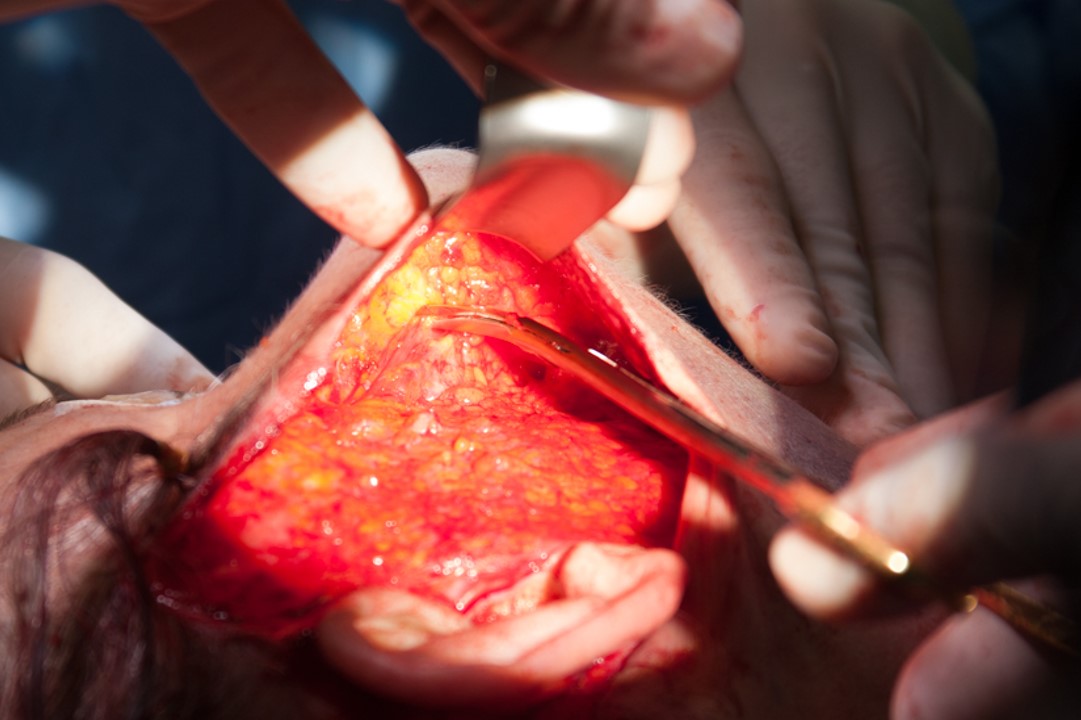

Hematoma. Hematoma is the most common complication following rhytidectomy, with a reported incidence of 0.2% to 8% (see Image. Midline Dehiscence of the Muscles).[21] Hematomas can be categorized as either major or minor. Major bleeding episodes often occur within 24 hours of surgery with symptoms of subcutaneous mass, pain, and ecchymotic skin discoloration; these require surgical intervention to control the hemorrhage. If this occurs in the neck, airway compromise may ensue, and the wound should be opened emergently. In contrast, minor bleeding tends to be delayed and may result from oozing of the subdermal plexus. These episodes can often be managed with watchful waiting or bedside drainage.

The risk of hematoma is increased by several factors, including hypertension, male gender, coagulopathy or use of anticoagulants, post-anesthesia nausea, vomiting, and pain. Male skin is more vascular than female because of its hair follicles, which leads to a greater risk of bleeding. The use of antiplatelet medications or anticoagulants like aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and herbal supplements that are known to increase bleeding, such as Ginkgo biloba, turmeric, St. John's wort, ginseng, high dose vitamin C and E, fish oils, garlic, and glucosamine should also be stopped two weeks prior to surgery.[22]

Hypertension remains the most significant risk factor contributing to hematoma formation. The goal is to maintain blood pressure below 150/90 mmHg. Baker et al. demonstrated a reduction in the overall incidence of postoperative hematoma in male rhytidectomy patients from 8.7% to 3.97% with strict blood pressure controls.[23] Preoperatively, sympatholytic medications, such as valium or clonidine, may be administered. Intraoperatively, meticulous hemostasis should be achieved before closure. Postoperatively, factors that can increase agitation in recovering patients, such as nausea and pain, should also be addressed promptly. The effect of drain placement on hematoma formation is unclear; however, drains may be able to reduce seroma formation.

Skin necrosis. This is often due to microvascular compromise from seroma or hematoma formation and comorbid conditions such as smoking and diabetes. Laser skin resurfacing performed on the lateral cheek under the same anesthetic as the rhytidectomy will also increase the risk of skin necrosis. Skin necrosis can involve partial-thickness or full-thickness dermis with eschar formation. In partial-thickness necrosis, patients present with skin discoloration and desquamation. This usually resolves with conservative wound care and heals well without scarring. Nitropaste or dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) may be considered to improve perfusion. Full-thickness necrosis will lead to prolonged healing time with skin abnormalities such as dyspigmentation, contour irregularities, and scarring and may require further intervention. Wounds must be allowed to declare themselves completely, and that early debridement is to be avoided ito avoid further damage.

The most significant risk factor for skin necrosis among rhytidectomy patients is smoking. Cigarette smoke contains nicotine, carbon monoxide, hydrogen cyanide, and nitric oxide, all of which have detrimental effects on microvascular oxygen transport and impair wound healing. In 1984, Rees et al. showed a skin sloughing rate of 7.5% in smokers compared to 2.7% in nonsmokers who underwent rhytidectomy; given the increased risk of skin necrosis with smoking, some authors feel that the deep-plane facelift is safer in smokers because the thicker flap results in better perfusion.[24][25] Two to four weeks of smoking cessation before and again after surgery is strongly recommended to avoid skin necrosis.[26] Medications that can alter wound healing, such as chemotherapy and steroids, are also essential to consider prior to rhytidectomy. Patients taking these medications should delay the rhytidectomy until some time after the course is complete or even cancel the procedure.

Lastly, skin closure should be performed without tension to avoid ischemia at the wound edges. The distal aspects of the flap, in the preauricular and superior postauricular areas, are the most susceptible to ischemic injury and, therefore, the most likely to develop necrosis.

Of note, patients undergoing revision rhytidectomy may have a lower risk of developing skin necrosis because their skin flaps have effectively been delayed since the prior surgery and have improved perfusion through dilated choke vessels.

Nerve injury. With a reported incidence of 0.7% to 2.5%, nerve injury can best be avoided by understanding the relevant anatomy and employing careful surgical techniques.[23] The surgical landmarks described above are important to remember when performing facial dissection. Although intraoperative nerve monitors can help avoid nerve injuries, nerves are often injured by aggressive retraction and electrocautery, particularly when a vessel, like the facial or external jugular vein, begins to bleed near a nerve - the marginal mandibular or GAN, respectively. If a nerve is transected and the injury is recognized during surgery, immediate microsurgical epineurial repair is recommended. Motor nerve injuries may take a year to recover or may never fully recover, but they can often be managed in the meantime with botulinum toxin injections to the contralateral facial muscle groups to improve symmetry, particularly in the case of frontal or marginal mandibular branch injury.

The GAN is the most common nerve injured during rhytidectomy, particularly during posterior skin flap elevation. This can cause anesthesia to the inferior pinna and mastoid skin, with patients reporting difficulty placing earrings, using telephones, or combing their hair.[7] The frontal and marginal mandibular branches of the facial nerve are the most commonly injured motor nerves during rhytidectomy.[6] Careful elevation of the subcutaneous flap over the zygomatic arch and the sub-platysmal flap around the angle of the mandible will help avoid injury to these nerves; if bleeding occurs in these areas, pressure and a clotting agent, such as thrombin or cellulose, should be applied rather than electrocautery.

Surgical site infection. Fortunately, cellulitis or abscess formation is a rare complication due to the robust blood supply of the face. Wound infections are most commonly caused by gram-positive cocci such as Staphylococcus or Streptococcus, and they generally resolve with antibiotics targeting skin flora.

Scarring and skin irregularities. While the incisions used for facelifts tend to be lengthy, careful placement can usually minimize their appearance postoperatively. When scars widen, they tend to do so in the postauricular area, generally due to excessive tension at closure; fortunately, they are rarely noticeable in this location. Widened, pigmented, or erythematous scars in the preauricular area can be treated with laser resurfacing, steroid injections, or potentially with hydroquinone. Avoiding sunlight exposure for the first 12 months after surgery will also help prevent noticeable scars. Hypertrophic or keloid scars may also benefit from silicone sheeting or operative revision after 6 to 12 months.

Another related complaint is subdermal contour irregularities, which often result from plication or imbrication of the SMAS, particularly when the overlying subdermal flap is very thin. Steroid injection and massage will usually alleviate these concerns.

Additionally, several named deformities also may result from improper soft tissue manipulation. A "pixie ear" deformity occurs when excessive tension is placed across the skin closure inferior to the auricular lobule; in this case, the lobule stretches inferiorly and creates the appearance of an elongated, attached ear lobe. Treatment may require a V to Y advancement of the lobule and re-elevation of the neck flap to decrease tension on the closure. A "cobra neck" deformity occurs when too much adipose tissue is removed from the central submental region, between the anterior bellies of the digastric muscles, without removing a commensurate volume from the lateral submentum and upper neck; this hollowing beneath the chin is reminiscent of a cobra's hood, hence the name. Fat transfer with either grafts or injections will ameliorate the problem. Lastly, the "wind-swept" look that may occur, especially after deep-plane face lifting, can be a result of overly aggressive lateralization of the malar fat pads or excessive tension on the cheek flaps, thereby widening the distance between the oral commissures; this is a difficult problem to repair, but it may be improved with a revision facelift performed several months later, providing enough time for tissue relaxation to permit redraping of the facial flaps without tension.

Alopecia and malposition of the hairline. This is often caused by injury to hair follicles during incision, aggressive use of electrocautery, or closure under excessive tension. Beveling the scalpel blade during incision, either parallel or perpendicular to the hair follicles, may minimize the appearance of the scar. Surgeons should also make patients aware of the possibility of post-surgical telogen effluvium, in which diffuse hair loss occurs approximately three months after surgery. This condition can be observed or treated with minoxidil but should resolve spontaneously within six months. If alopecia does occur, allow 6-12 months of healing prior to hair transplantation to rule out telogen effluvium as an etiology.

When planning incisions, it is important not to disrupt the natural hairline, which can occur if attention is not paid to avoiding a step-off of the hairline when redraping postauricular skin before closure. A pre-tragal incision should be used in male patients to avoid posteriorly displacing the sideburns too close to the auricle or even onto the tragus.

First bite syndrome This has been reported with deep plane rhytidectomy and may be a result of damage to postganglionic parasympathetic nerve fibers to the parotid gland, similar to what may occur during deep lobe parotidectomy or parapharyngeal space surgery.[19] Aberrant reinnervation results in a painful hypercontraction of myoepithelial cells within the parotid gland at the beginning of meals; the pain usually subsides with subsequent bites. While it is unpleasant for patients, it can often be relieved with botulinum toxin injections and will generally resolve spontaneously within 6 to 12 months.

Patient dissatisfaction. Perhaps the most common complication is patient dissatisfaction with the surgical outcome. Approximately 30% of patients will experience depression after the face lifting, which may require anything from reassurance to anti-depressants.[27] It is crucial to consider the patient's psychiatric history preoperatively because it may indicate a risk for postoperative depression, which can contribute to dissatisfaction with the surgical result. In some cases, dissatisfaction may be unavoidable, and many patients will require a "tuck-up" procedure within 1 to 2 years of the initial surgery, particularly for isolated areas of persistent or recurrent soft tissue ptosis. Ordinarily, a 5 to 10-year interval between facelifts is expected to maintain a favorable result.

Clinical Significance

According to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, rhytidectomy is among the top 5 most commonly performed cosmetic surgical procedures, with over 120,000 performed in 2019. It is, therefore, important for aesthetic surgeons to understand its history, relevant anatomy, and technical nuances. Surgeons must possess meticulous surgical techniques and excellent relationship-building skills to achieve optimal patient outcomes.

Each facelift is an individualized procedure with outcomes dependent on patient selection, surgical approach, and postoperative management. It is important to obtain a complete medical history and perform a thorough physical exam to identify appropriate candidates for the procedure. Medical comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension or behaviors such as smoking or using herbal supplements can significantly increase the risk of complications. Additionally, outcomes and satisfaction improve when a strong doctor-patient rapport and realistic expectations are established before the surgery.

Determining the ideal approach to rhytidectomy depends on the patient's aesthetic goals, the effects of aging on their soft tissues, and the surgeon's experience. Variations of rhytidectomy, such as SMAS rhytidectomy, deep-plane rhytidectomy, and MACS lift, address different facial subunits to varying degrees. It is also important to recognize that face lifting is only one of many treatment modalities available for facial rejuvenation. Adjuvant therapies such as blepharoplasty, cervicoplasty, liposuction, injectable treatments, and skin resurfacing should be considered at the time of surgery to optimize the outcome.

Lastly, postoperative care is critical; ensuring that patients follow instructions and have easy access to the surgeon or nurse if complications develop will help minimize adverse outcomes through timely intervention.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Rhytidectomy is a procedure that constitutes one of the primary means by which surgeons are able to address the effects of aging on the face. As an elective aesthetic procedure, it is best approached with a coordinated healthcare team to achieve optimal results. In the preoperative phase, developing good patient rapport is critical, as this will facilitate a smoother postoperative course, particularly if complications arise. Communication and coordination with primary care providers and specialists in managing comorbidities are also critical, as proceeding with elective surgery without minimizing cardiopulmonary risks preoperatively is unnecessarily dangerous. Likewise, smoking is known to cause poor wound healing. [Level 3] Smoking cessation for 2 to 4 weeks before and after surgery is thought to reduce the risk of skin necrosis.[26] [Level 5]

Peri-operatively, a team effort from circulating nurses, surgical technologists, anesthesiologists, and the surgeon is required to provide high-quality surgical care. Optimal retraction from assistants can facilitate soft tissue dissection and hemostasis to avoid nerve injury and reduce anesthesia time. [Level 5] The use of propofol during general anesthesia may contribute to less postoperative nausea and, together with strict control of blood pressure (<150/90 mmHg), may help reduce the risk of postoperative hematoma.[21] [Level 3]

An interdisciplinary and interprofessional collaborative effort is required to provide optimal patient-centered care. Communication focused on clarifying the patient's aesthetic goals and setting realistic expectations can help improve postoperative satisfaction. Risk factors for complications should be carefully minimized before the procedure.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Mangat DS, Frankel JK. The History of Rhytidectomy. Facial plastic surgery : FPS. 2017 Jun:33(3):247-249. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1603347. Epub 2017 Jun 1 [PubMed PMID: 28571059]

Mitz V, Peyronie M. The superficial musculo-aponeurotic system (SMAS) in the parotid and cheek area. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1976 Jul:58(1):80-8 [PubMed PMID: 935283]

Hamra ST. Building the Composite Face Lift: A Personal Odyssey. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2016 Jul:138(1):85-96. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002310. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26986987]

Whitney ZB, Jain M, Zito PM. Anatomy, Skin, Superficial Musculoaponeurotic System (SMAS) Fascia. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30085556]

DAVIS RA, ANSON BJ, BUDINGER JM, KURTH LR. Surgical anatomy of the facial nerve and parotid gland based upon a study of 350 cervicofacial halves. Surgery, gynecology & obstetrics. 1956 Apr:102(4):385-412 [PubMed PMID: 13311719]

Hohman MH, Bhama PK, Hadlock TA. Epidemiology of iatrogenic facial nerve injury: a decade of experience. The Laryngoscope. 2014 Jan:124(1):260-5. doi: 10.1002/lary.24117. Epub 2013 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 23606475]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLefkowitz T, Hazani R, Chowdhry S, Elston J, Yaremchuk MJ, Wilhelmi BJ. Anatomical landmarks to avoid injury to the great auricular nerve during rhytidectomy. Aesthetic surgery journal. 2013 Jan:33(1):19-23. doi: 10.1177/1090820X12469625. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23277616]

Dedo DD. "How I do it"--plastic surgery. Practical suggestions on facial plastic surgery. A preoperative classification of the neck for cervicofacial rhytidectomy. The Laryngoscope. 1980 Nov:90(11 Pt 1):1894-6 [PubMed PMID: 7432071]

Pitanguy I, Ramos AS. The frontal branch of the facial nerve: the importance of its variations in face lifting. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1966 Oct:38(4):352-6 [PubMed PMID: 5926990]

Dorafshar AH, Borsuk DE, Bojovic B, Brown EN, Manktelow RT, Zuker RM, Rodriguez ED, Redett RJ. Surface anatomy of the middle division of the facial nerve: Zuker's point. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2013 Feb:131(2):253-257. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182778753. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23357986]

Batra AP, Mahajan A, Gupta K. Marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve: An anatomical study. Indian journal of plastic surgery : official publication of the Association of Plastic Surgeons of India. 2010 Jan:43(1):60-4. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.63968. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20924452]

Chowdhry S, Yoder EM, Cooperman RD, Yoder VR, Wilhelmi BJ. Locating the cervical motor branch of the facial nerve: anatomy and clinical application. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2010 Sep:126(3):875-879. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181e3b374. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20463628]

Hwang K, Son JS, Ryu WK. Smoking and Flap Survival. Plastic surgery (Oakville, Ont.). 2018 Nov:26(4):280-285. doi: 10.1177/2292550317749509. Epub 2018 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 30450347]

Goldminz D, Bennett RG. Cigarette smoking and flap and full-thickness graft necrosis. Archives of dermatology. 1991 Jul:127(7):1012-5 [PubMed PMID: 2064398]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAdamson PA, Litner JA. Evolution of rhytidectomy techniques. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2005 Aug:13(3):383-91 [PubMed PMID: 16085284]

Rohrich RJ, Sinno S, Vaca EE. Getting Better Results in Facelifting. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. Global open. 2019 Jun:7(6):e2270. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002270. Epub 2019 Jun 27 [PubMed PMID: 31624678]

Joshi K, Hohman MH, Seiger E. SMAS Plication Facelift. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30285353]

Hamra ST. The deep-plane rhytidectomy. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1990 Jul:86(1):53-61; discussion 62-3 [PubMed PMID: 2359803]

Gunter AE, Llewellyn CM, Perez PB, Hohman MH, Roofe SB. First Bite Syndrome Following Rhytidectomy: A Case Report. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2021 Jan:130(1):92-97. doi: 10.1177/0003489420936713. Epub 2020 Jun 21 [PubMed PMID: 32567395]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTonnard P, Verpaele A. The MACS-lift short scar rhytidectomy. Aesthetic surgery journal. 2007 Mar-Apr:27(2):188-98. doi: 10.1016/j.asj.2007.01.008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19341646]

Baker DC, Stefani WA, Chiu ES. Reducing the incidence of hematoma requiring surgical evacuation following male rhytidectomy: a 30-year review of 985 cases. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2005 Dec:116(7):1973-85; discussion 1986-7 [PubMed PMID: 16327611]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChaffoo RA. Complications in facelift surgery: avoidance and management. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2013 Nov:21(4):551-8. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2013.07.007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24200374]

Baker DC, Conley J. Avoiding facial nerve injuries in rhytidectomy. Anatomical variations and pitfalls. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1979 Dec:64(6):781-95 [PubMed PMID: 515227]

Rees TD, Liverett DM, Guy CL. The effect of cigarette smoking on skin-flap survival in the face lift patient. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1984 Jun:73(6):911-5 [PubMed PMID: 6728942]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceParikh SS, Jacono AA. Deep-plane face-lift as an alternative in the smoking patient. Archives of facial plastic surgery. 2011 Jul-Aug:13(4):283-5. doi: 10.1001/archfacial.2011.39. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21768564]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRinker B. The evils of nicotine: an evidence-based guide to smoking and plastic surgery. Annals of plastic surgery. 2013 May:70(5):599-605. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3182764fcd. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23542839]

Goin MK, Burgoyne RW, Goin JM, Staples FR. A prospective psychological study of 50 female face-lift patients. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1980 Apr:65(4):436-42 [PubMed PMID: 7360810]