Introduction

The human spine consists of seven cervical vertebrae, twelve thoracic vertebrae, five lumbar vertebrae, five fused sacral vertebrae, and 3 to 5 fused coccyx vertebra. In the normal human spine, there is some degree of kyphosis in the thoracic spine and some degree of lordosis in the cervical and lumbar spine. Kyphosis is defined as an increase in the forward curvature of the spine that is seen along the sagittal plane, whereas lordosis is an increase in the backward curvature seen along the sagittal plane. When the forward curvature becomes excessive, this is called hyperkyphosis. Note that this is different than scoliosis, which is the curvature of the spine along the frontal plane. The biomechanics that influences the curvature lies in the shape of the vertebral body and intervertebral disc, with an anterior wedge increasing the angle of kyphosis.[1] The natural history of kyphosis is not exactly well known; however, an increased amount of curvature in the thoracic spine is seen starting at the age of 40 years old with women having a more rapid rate compared to men.[2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The three main types of kyphosis usually seen in individuals are postural kyphosis, Scheuermann disease, and congenital deformities. Postural kyphosis usually starts to show up in adolescents, with more females being affected compared to males. The slouching posture increases the forward curvature, which will, in turn, stretch the extensor muscles of the back and the posterior ligaments of the spine, thereby weakening it over time.[3] Postural kyphosis will usually have normal vertebral structures, and the condition usually has a benign course. In older individuals, the decreased integrity of the muscles can contribute to the poor posture, which can cause an increased compressive load on the thoracolumbar spine over time, thereby producing an anterior wedge-like fracture that we usually see in the elderly with osteoporotic compression fractures.[4]

Scheuermann disease, also known as juvenile kyphosis, is a structural deformity of the thoracic/thoracolumbar spine that usually occurs before puberty. It is thought that the discordant mineralization of the vertebral endplate and ossification during growth and development causes an anteriorly wedged vertebral body.[5] Although the mode of transmission is not entirely known, there are reports of identical radiographic findings in monozygotic twins with Scheuermann’s disease, suggesting a hereditary component.[6]

Congenital kyphosis is an uncommon cause of hyperkyphosis but can be severely disabling, rapidly progressive, and is more commonly associated with neurological complications compared to the other causes of kyphosis.[7] There are two types of congenital kyphosis: failure of formation (type 1) and failure of segmentation (type 2). In the failure of formation, 1 or more vertebral bodies will fail to develop, thereby resulting in a kyphosis that will get worse as the child grows. In the failure of segmentation, 2 or more vertebral bodies will fail to separate. This type of deformity will usually be diagnosed after a child begins walking. Besides tuberculosis, congenital kyphosis is the most common cause of spinal cord compression from spinal deformities.[8]

In addition to the three causes listed above, there are many other causes, such as an increase in age, injuries inflicted on the spine, osteoporosis, slipped disc, infections in the spine, and malignancies.

Epidemiology

Hyperkyphosis, in general, increases with age, especially after the age of 40, and the prevalence is about 20% to 40% in adults 60 years or older.[2] Although both females and males are affected, females have a greater rate of increase, especially during menopause.[2] Age-related kyphosis is usually from underlying osteoporosis and/or fractures, although upon radiographic examination, we only see vertebral fractures in one-third of those with severe kyphosis.[2] In a longitudinal study that included 100 healthy participants, including both males and females at least the age of 50, the average thoracic kyphotic angle was noted to increase about 3 degrees per decade.[2]

In Scheuermann’s disease, the prevalence is about 0.4% to 8% in the United States, with males being twice as likely to have it compared to females. Most cases are diagnosed between the ages of 13 to 16 years old and are rarely diagnosed under the age of 10.

History and Physical

The most obvious sign seen in hyperkyphosis is the cosmetic deformity seen as a rounded back due to the excessive forward curvature of the spine. As mentioned above, this deformity starts to appear after the age of 40 in age-related kyphosis, whereas the excessive curvature can begin to be appreciated in adolescents for postural kyphosis (normal vertebral structures) and Scheuermann disease (vertebral structural deformity). In addition to the cosmetic deformity, patients will also commonly display back pain ranging from mild to severe, fatigue, the pain worsened with movement, increased forward posture of the head, and uneven shoulder height. With more severe cases, patients can have chest pain, shortness of breath, weakness, and/or loss of sensation, and bowel/bladder incontinence.

For the physical examination, the exam is generally broken down into observation, palpation, and range of motion testing. In severe cases, upon observation in the sagittal plane, the upper back will have a rounded appearance, oftentimes described as a "hump". In milder cases, the "hump" in the back may not be apparent. Upon palpation, the paraspinal muscles will typically be tender. Of note, tight hamstrings are associated with Scheuermann disease, which are thought to be "lumbar compensators" and can cause an overcompensation, thereby increasing the risk of imbalance in these populations.[9] For the range of motion of the thoracolumbar spine, the normal values are 90 degrees for flexion, 30 degrees for extension, lateral side bending, and rotation. In hyperkyphosis, there will be stiffness and loss of range of motion. One distinctive feature that will separate postural kyphosis from a structural kyphosis such as Scheuermann disease is a flexible curve with the spine straightening when the patient is laying down on his or her back signifying that the origin is a postural issue rather than a structural one, where the curved spine would be rigid rather than flexible.

Lastly, it is important to examine the neurological system for patients with hyperkyphosis. Although there are typically no neurological findings in most cases, the most severe kyphosis can present with numbness, tingling, weakness, bowel, and bladder incontinence. In these cases, an MRI should be ordered to rule out cord compression.

Evaluation

As mentioned before, a small degree of kyphosis is normal, given the structure and shape of the vertebral bodies and disc. However, when the angle of kyphosis is more than 40 degrees, which is the 95th percentile for young adults, we then call this hyperkyphosis.[10]

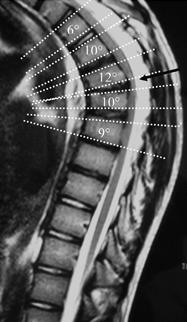

The gold standard for the objective assessment of kyphosis is obtaining a standing lateral spine X-ray. Of note, the patient can be supine instead for comfort in the elderly population. When analyzing the lateral spinal X-ray, to make the diagnosis of kyphosis, the Cobb's angle must be calculated. To do this, find the superior endplate of the vertebra that forms the beginning of the curve and the inferior endplate of the vertebra that forms the end of the curve. Draw a straight line through both the superior and inferior endplates, and the Cobb's angle will be the measured angle of these intersected lines.[10] For Scheuermann disease, in addition to Cobb's angle being greater than 40 degrees, there also needs 3 or more of the adjacent vertebral bodies to have an anterior wedge that is measured 5 degrees or more. To measure this on the X-ray, a line is drawn on the superior and inferior endplates of the vertebral body being measured with the lines intersecting as the measured anterior wedge angle.[11]

There are, however, alternatives if radiographs are unable to be obtained. The Debrunner kyphometer, as well as the flexicurve ruler, are two acceptable alternatives in place of radiographs for assessing hyperkyphosis.[10] The kyphometer is a protractor device where the two arms are placed at the top and bottom of the curve of the thoracic region. The angle is then read on the protractor.[10] The flexicurve ruler, a moldable plastic device, is placed in the C7 and the L5-S1 lumbosacral space. A kyphosis index is then calculated by using the width of the thoracic curve divided by the length of the thoracic curve multiplied by 100. An index greater than 13 is considered hyperkyphotic.[10] An easy way to conceptualize this is realizing that the greater the degree of thoracic angle, the greater the width of the thoracic width and the lesser the height of the thoracic length, thereby increasing the index.

Treatment / Management

The course of treatment for kyphosis will generally be starting conservatively and progressing to surgical intervention as a last resort if the patient’s symptoms do not improve with conservative management or if the curvature is too significant.

Conservative management will consist of observation, physical therapy, and the use of NSAIDs. The indications for conservative management are for patients with kyphosis that is less than 60 degrees.[12] Observation will consist of regular visits to a physician with x-rays to trend the progression of the curve. Physical therapy will be used to strengthen the back and abdominal muscles. This will relieve pressure on the spine, helping to improve posture and reduce discomfort. Stretching exercises and cardiovascular activities are also prescribed to help alleviate back pain and fatigue. Doctors usually recommend that people with postural kyphosis receive non-surgical forms of treatment. Of note, many men and women with hyperkyphosis are treated for osteoporosis with anti bone resorptive medications or bone-building medications to prevent spinal fractures but do not fix the kyphosis itself.[10]

Bracing should be considered for adolescents who have kyphosis greater than 50 degrees.[12] The idea behind this is that the brace will guide the growth of the spine to straighten it out. According to studies done by Lowe TG, adolescents with kyphosis between 55 degrees to 80 degrees will almost always be successful with bracing if the treatment is done before skeletal maturity.[13] Thus for skeletally mature patients, bracing will not correct the curvature itself but can be used as support and pain relief. The most common brace used is the Milwaukee brace and is usually worn for 16 to 24 hours a day per year.

The following are indications when surgery may be the appropriate course of action to take: pain not improving with a conservative approach, progressing curve, neurological deficits, cardiopulmonary compromise, and worsening trunk deformity (usually with kyphosis greater than 75 degrees). In age-related kyphosis where osteoporotic fractures of the vertebral bodies can happen and thus leading to kyphosis, two surgical approaches that can be considered are kyphoplasty and vertebroplasty (these approaches are mainly to treat refractory pain from vertebral compression fractures).[14] For patients with Scheuermann disease, the surgical approach is usually a combination of anterior release with fusion and the addition of posterior instrumentation with fusion. However, recent cases have reported a posterior only approach that offers a greater correction rate and has been gaining popularity in recent years.[15](A1)

In congenital kyphosis, surgical treatment will need to be implemented due to the progressive nature of the disease. Conservative management will not prevent the likely catastrophic deformity and neurological compromise these patients can/will have.[8] Ideally, a posterior fusion approach would be implemented for those younger than 5 years old, and with curvature, less than 50 degrees, whereas an anterior and posterior fusion approach would be used in those older than 5 years old over 60 degrees.[8] For those already with cord compression, laminectomies are contraindicated, and instead, an anterior cord decompression with fusion will need to be used.[8]

Differential Diagnosis

Vertebral Instability

This is usually secondary to an inciting event or gradual progression of a degenerative disease. Patients will have spine evaluated by laxity or surrounding muscles and stabilization techniques.

Scheuermann Disease

Scheuermann disease is a juvenile condition usually occurring before puberty where kyphotic changes become present.

Ankylosing Spondylitis

AS is an inflammatory condition usually associated with other systemic disorders such as psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease, and reactive arthritis. Xray findings are also unique to this condition and help diagnose the condition.

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a progressive degenerative disease of loss of bone mineralization evident throughout all bones in varying degrees. Bone scan, Xray, and MRI can help diagnose and qualify these findings.

Vertebral Fracture

Fractures can also cause kyphosis through an inciting traumatic event or even cancer causing the loss of bone integrity. Proper history and medications will help delineate the etiology of the kyphosis.

Prognosis

Normal variants exhibit no limitations or issues with function. Extremes of curvature may lead to back pain, respiratory complications, and limitations to the quality of life. The condition may be self-limiting, improved with physical therapy, or surgically corrected with spine surgery.

Complications

The curvature of the spine may lead to back pain and limitations to the quality of life. In more severe cases, it can lead to cardiopulmonary and neurological compromise.

The most common postoperative complications in treating kyphosis are postoperative infections and bleeding around the surgical site.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education plays an important role in the management of kyphosis if the condition leads to functional limitations. Individuals need to focus on conservative measures such as physical therapy, proper posture, and body mechanics. Developing core stability muscle strength may play a role in spine stability.

In age-related kyphosis, it is important to tell the patients, especially the female population, to avoid flexion exercises since research has shown that flexion induced movements can increase the risk of fractures when bone strength is impaired.[10] The focus should be on extension based exercises to focus on strengthening the back extensor muscles since these muscles are known to be weak for hyperkyphosis.[10]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Although traditionally a normal variant presentation, extremes of this condition may warrant further investigation. Communication in terms of presentation and understanding of patients is vital when managing kyphosis to better identify and address patient concerns when necessary. An interprofessional team can consist of primary care, radiology, rheumatology, physiatrists, nurses, and physical therapists. The team can improve outcomes with patient-centered care.[Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Rohlmann A, Klöckner C, Bergmann G. [The biomechanics of kyphosis]. Der Orthopade. 2001 Dec:30(12):915-8 [PubMed PMID: 11803743]

Roghani T, Zavieh MK, Manshadi FD, King N, Katzman W. Age-related hyperkyphosis: update of its potential causes and clinical impacts-narrative review. Aging clinical and experimental research. 2017 Aug:29(4):567-577. doi: 10.1007/s40520-016-0617-3. Epub 2016 Aug 18 [PubMed PMID: 27538834]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSingla D, Veqar Z. Association Between Forward Head, Rounded Shoulders, and Increased Thoracic Kyphosis: A Review of the Literature. Journal of chiropractic medicine. 2017 Sep:16(3):220-229. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2017.03.004. Epub 2017 Sep 28 [PubMed PMID: 29097952]

Keller TS,Harrison DE,Colloca CJ,Harrison DD,Janik TJ, Prediction of osteoporotic spinal deformity. Spine. 2003 Mar 1; [PubMed PMID: 12616157]

Sardar ZM, Ames RJ, Lenke L. Scheuermann's Kyphosis: Diagnosis, Management, and Selecting Fusion Levels. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2019 May 15:27(10):e462-e472. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-17-00748. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30407981]

McKenzie L,Sillence D, Familial Scheuermann disease: a genetic and linkage study. Journal of medical genetics. 1992 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 1552543]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKale P, Dhawas A, Kale S, Tayade A, Thakre S. Congenital kyphosis in thoracic spine secondary to absence of two thoracic vertebral bodies. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2015 Jan:9(1):TD03-4. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/11275.5431. Epub 2015 Jan 1 [PubMed PMID: 25738059]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWinter RB. Congenital kyphosis. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1977 Oct:(128):26-32 [PubMed PMID: 598164]

Hosman AJ, de Kleuver M, Anderson PG, van Limbeek J, Langeloo DD, Veth RP, Slot GH. Scheuermann kyphosis: the importance of tight hamstrings in the surgical correction. Spine. 2003 Oct 1:28(19):2252-9 [PubMed PMID: 14520040]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKatzman WB, Wanek L, Shepherd JA, Sellmeyer DE. Age-related hyperkyphosis: its causes, consequences, and management. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. 2010 Jun:40(6):352-60. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2010.3099. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20511692]

Makurthou AA, Oei L, El Saddy S, Breda SJ, Castaño-Betancourt MC, Hofman A, van Meurs JB, Uitterlinden AG, Rivadeneira F, Oei EH. Scheuermann disease: evaluation of radiological criteria and population prevalence. Spine. 2013 Sep 1:38(19):1690-4. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31829ee8b7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24509552]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePatel DR, Kinsella E. Evaluation and management of lower back pain in young athletes. Translational pediatrics. 2017 Jul:6(3):225-235. doi: 10.21037/tp.2017.06.01. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28795014]

Weiss HR, Turnbull D, Bohr S. Brace treatment for patients with Scheuermann's disease - a review of the literature and first experiences with a new brace design. Scoliosis. 2009 Sep 29:4():22. doi: 10.1186/1748-7161-4-22. Epub 2009 Sep 29 [PubMed PMID: 19788753]

Pradhan BB, Bae HW, Kropf MA, Patel VV, Delamarter RB. Kyphoplasty reduction of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures: correction of local kyphosis versus overall sagittal alignment. Spine. 2006 Feb 15:31(4):435-41 [PubMed PMID: 16481954]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHuq S, Ehresman J, Cottrill E, Ahmed AK, Pennington Z, Westbroek EM, Sciubba DM. Treatment approaches for Scheuermann kyphosis: a systematic review of historic and current management. Journal of neurosurgery. Spine. 2019 Nov 1:32(2):235-247. doi: 10.3171/2019.8.SPINE19500. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31675699]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence