Introduction

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) can be caused by any external mechanical forces, impact, rapid acceleration-deceleration, or penetrating injury to the head and presents a significant health challenge worldwide. This article primarily addresses those suffering from a traumatic brain injury or closed head injury, which is the most common form of TBI, rather than a penetrating head injury. The various types of closed head injuries include conditions like concussion, parenchymal contusions, and various types of intracranial hematomas. In the United States, TBI affects approximately 1.7 million individuals annually, with a noticeable prevalence among older adolescents (ages 15 to 19 years old) and adults over the age of 65. These injuries frequently impact the frontal and temporal brain regions, leading to substantial healthcare burdens, particularly in lower-income countries.[1][2][3][4]

TBI severity is classified into three categories: mild, moderate, and severe. Mild TBI or concussion is clinically defined as a loss of consciousness lasting <30 minutes, post-traumatic amnesia lasting <24 hrs, or any alteration of consciousness. Moderate or severe TBI is clinically defined as a loss of consciousness lasting ≥ 30 minutes to prolonged coma, post-traumatic amnesia lasting ≥24 hours up to permanently, or a Glasgow Coma score as low as 3.

A Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score is also used in the description of those with TBI. It is scored out of 15, where it is defined as mild when the GCS is 14-15, moderate when the GCS is 9-12, and severe when the GCS is 3-8. A mild TBI (otherwise known as a concussion) comprises over 90% of the cases.[5][6] Symptoms vary widely, from transient consciousness to prolonged unconsciousness or coma in severe cases. Long-term risks include persistent postconcussive symptoms, such as headaches, dizziness, difficulty concentrating, and depression. Recurrent TBIs can lead to cumulative, permanent neurologic damage and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), emphasizing the critical need for research and education to understand the long-term effects of TBI.[7][8][9][10][9]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Traumatic brain injuries can occur from minor impacts or blows to the head, large blows from significant impact, and penetrating injuries to the head. TBI can also occur secondary to rapid acceleration and deceleration of the brain without impact, resulting in diffuse axonal injury (DAI), and can be very debilitating. [11][12] Depending on the scenario, they can all lead to various degrees of TBI. Statistically, falls are the most common cause of TBI, responsible for 49% of TBI-related emergency department visits in children aged 0 to 17 years and 81% in adults aged 65 years and older. The second most common cause of TBI is motor vehicle collisions/traffic-related injuries, followed by sports or work-related injuries and assaults.[13][14] For patients requiring hospitalization due to TBI, falls account for 52% of cases, while motor vehicle accidents are responsible for 20%.[15] Penetrating and blast-related head injuries are the most lethal form of head trauma.[16]

Epidemiology

It is reported that almost 70 million individuals are estimated to suffer from some form of TBI, which is seen more commonly in males than females and occurs more in children, adults up to 24 years, and those older than 75.[17][18][19][20] Mild TBI is the most common form of TBI and comprises over 90% of cases presenting acutely to the hospital.[21] Although only 10% of TBIs occur in the elderly, they account for up to 50% of head trauma-related deaths. In middle and low-income nations, most head trauma results from road traffic accidents.[21] These are reported to be the highest in Africa and Southeast Asia.[17] In high-income nations, most TBI cases occur related to falls secondary to age-related frailty and alcohol misuse.[21] This group encompasses a considerable portion of the global injury burden.[22] The Global Burden of Disease study reported a worldwide age-standardized head trauma incidence of 346 per 100,000 people in 2019. In 2016, it was estimated that TBI resulted in 8.1 million years lived with disability and a pooled age-standardized rate of about 160 years of life lost per 100,000 people.[21]

Pathophysiology

Traumatic brain injury following head trauma results from primary and secondary injury/insults.

Primary Injury

Primary injury includes injury upon the initial impact that causes displacement of the brain due to direct impact, rapid acceleration-deceleration, or penetration. These injuries may cause skull fractures, cerebral contusions, hematomas (epidural, subdural, intraparenchymal, intraventricular, or subarachnoid), and diffuse axonal injury (DAI).

Secondary Injury

A secondary neurotoxic cascade occurs after the initial insult and is most commonly secondary to hypoxia, hypotension, and raised intracranial pressure. Neuropathogenesis implicated in secondary injury in head trauma include:

- Wallerian degeneration

- Mitochondrial dysfunction

- Glutamate hyper-excitotoxicity [23]

- Lactate storm

- Oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation

- Apoptotic cell death

- Neuroinflammation

- Impaired autophagy

- Impaired G-lymphatic pathways [24][25]

The glutamate hyper-excitotoxicity pathway describes when injured nerve cells secrete intracellular glutamate into the extracellular spaces. This then overstimulates a subtype glutamate receptor, allowing sodium and calcium influx into the injured nerve cell. This influx of ions activates various enzymes, which then degrade cell membranes and structure, leading to free radicals, cell death, and edema.[23]

According to the Monro-Kellie doctrine, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and cerebral blood volume (CBV) are the prime buffers against any extra volume increment inside the rigid skull.[26] Cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) may be estimated by measuring intracranial pressure (ICP) and the mean arterial pressure (MAP), CPP=MAP-ICP. ICP is a function of the relative amounts of CBV, brain parenchyma, and CSF in the inelastic space of the cranium. When raised, ICP overrides the compensatory displacement of the CSF and disrupts the cerebral autoregulatory capacity, leading to decreased brain compliance and a fall in compensatory reserve. This triggers sequential cascades of herniation syndrome, each showing salient neurological and radiological characteristics.[27] Subfalcine herniation leads to contralateral lower limb weakness due to pericallosal and callosomarginal vessel compression. Uncal herniation causes ipsilateral anisocoria with contralateral motor weakness. Furthermore, the torsion on the diencephalon alters the sensorium following distortion of the reticular activating system and obliteration of CSF pathways. The transtentorial herniation shows decorticate and decerebrate posturing alongside loss of brainstem reflexes. The patient may develop Cheyne-Stoke breathing followed by hyperventilation, ataxia, apnoea, and eventually respiratory arrest from tonsillar herniation.[27]

History and Physical

History

Important historical features, including the mechanism of injury and the presence of loss of consciousness (and, if so, for how long), are essential components in the initial evaluation. In addition to the mechanism of injury, the clinician must understand the patient's past medical history and whether or not there is any use of any antiplatelet or anticoagulation agents. Symptoms of TBI may be nonspecific and include nausea, vomiting, headaches, tinnitus, visual changes, dizziness, "foggy" feeling, or confusion. In the longer term, many patients struggle with ongoing post-concussive symptoms, including dizziness, balance problems, cognitive difficulties, memory deficits, emotional lability, anxiety, depression, sleep difficulties, delusions, hallucinations, vision changes, and headaches.

Exam

It is important to review initial vital signs in patients following a closed head injury. In patients with increased intracranial pressure of >20 mmHg (normal is <15 mmHg), the Cushing triad, a combination of hypertension, bradycardia, and irregular or decreased respirations, may be present.

Assuming that the patient's airway, breathing, and circulation are intact, the patient should be evaluated using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), assessing for eye-opening, verbal responses, and motor responses. The minimum score is 3, and the maximum score is 15.

Glasgow Coma Scale:[28]

Eye-opening response

- Spontaneous (4)

- To verbal stimuli (3)

- To pain (2)

- No response (1)

Verbal response

- Oriented (5)

- Confused (4)

- Inappropriate words (3)

- Incomprehensible speech (2)

- No response (1)

Motor response

- Obeys commands for movement (6)

- Purpose movement to painful stimuli (5)

- Withdraws to painful stimuli (4)

- Flexion response to painful stimuli (decorticate posturing) (3)

- Extension response to painful stimuli (decerebrate posturing) (2)

- No response (1)

Battle sign (bruising behind the ears), raccoon eyes (bruising beneath the eyes), hemotympanum, and CSF otorrhea or rhinorrhea are signs of basilar skull fracture and are highly associated with intracranial hemorrhage.[29] Pupil response is testable in all patients. A fixed, dilated pupil ("blown" pupil) on one side may correspond to ipsilateral hemorrhage and herniation.

In patients who can cooperate with the exam, a thorough neurologic exam, including assessment of cranial nerves, strength, sensation, reflexes, and clonus, should follow. Gait testing should be performed in patients not suspected of cervical spine injury, though most patients with a severe head injury will require cervical spine immobilization until cervical injury is clinically and radiologically ruled out. In patients who are following up after brain trauma, further neuropsychiatric testing may be necessary in those persistent symptoms.

Evaluation

Laboratory studies may be indicated in the acute evaluation of patients with TBI. The decision to obtain any laboratory studies will depend on the severity of the injury or associated polytrauma and the medical history of the patient. For example, a simple head injury following a ground-level fall with a resultant head contusion and no other trauma may only require imaging and no labs, whereas a head injury following an MVC in a patient with multiple other traumatic injuries who is also on an anticoagulant will likely need a full lab panel. When clinically indicated, common labs include a CBC, CMP, coagulation profile (PT and PTT), and a type and screen.

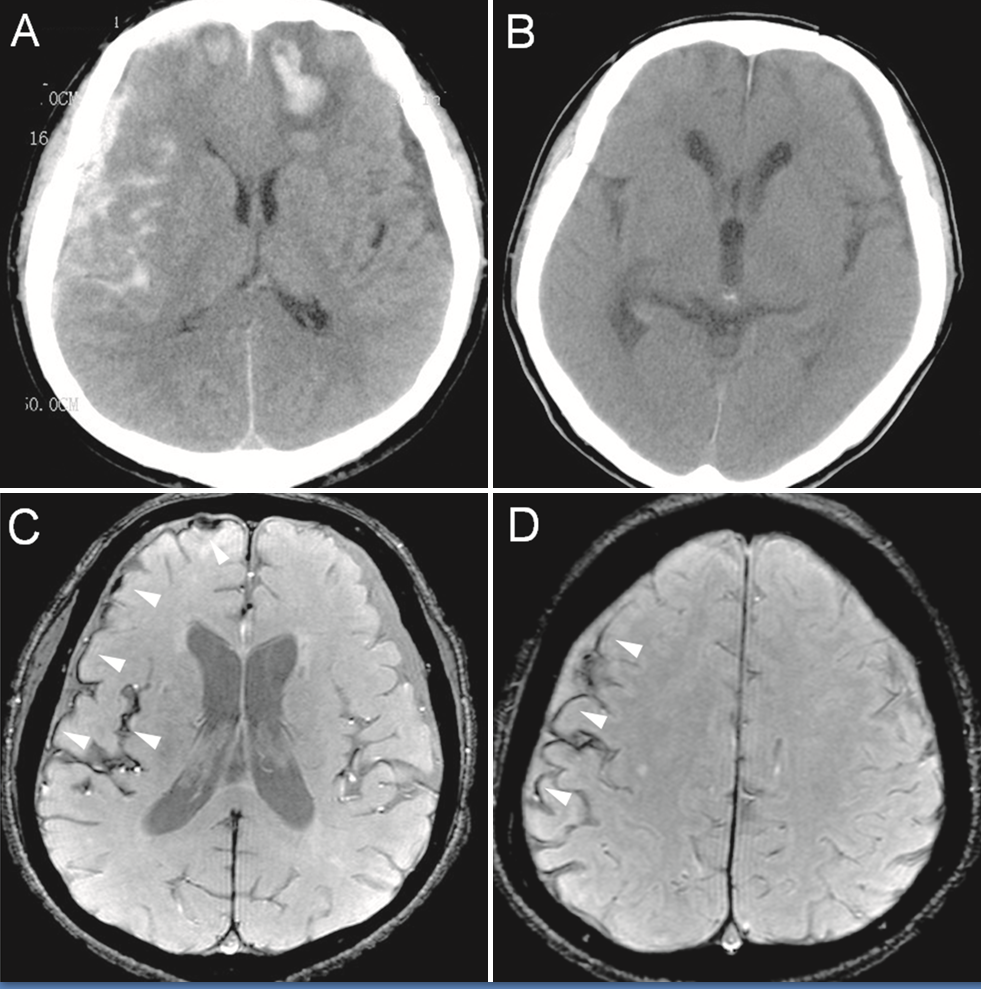

The initial imaging study of choice is a CT scan of the brain without contrast, as it is often readily available in just about any hospital setting and is rapidly obtainable. Skull X-rays are not recommended unless assessing foreign bodies, gunshots, or stab wounds due to their poor diagnostic value. MRI can be helpful but takes much longer to obtain than a head CT. MRI may be indicated in follow-up for head injuries but is not used as the initial evaluation.

A CT scan of the brain is advocated for patients with moderate to severe head injury as this helps rule out or diagnose the majority of intracranial emergencies like subdural, epidural, intraparenchymal, and subarachnoid hemorrhages. Those suffering from DAI may have normal initial CT scans, but some may reveal small punctate hemorrhages to white matter tracts. MRI imaging is best used to help diagnose DAI, especially diffuse tensor imaging (DTI) and gradient-recalled echo (GRD) MRI.[30] For adults with mild head injury (mild TBI) and are at low risk for intracranial injuries, there are two commonly used and externally validated scoring algorithms that help guide when to obtain a head CT scan after a head injury.[31][32][33][34][35] These are the New Orleans Criteria (NOC) and Canadian CT Head Injury/Trauma Rules (CCHR). For patients with minor head trauma and a GCS of 15, both rules have a 100% sensitivity in predicting the need for neurosurgical intervention with the CCHR, resulting in lower CT rates (52% vs. 88%) and being more specific (50.6% vs. 12.7%).[34] Similar to the CCHR and NOC, the PECARN head injury rule has a 100% sensitivity and 100% negative predictive value in ruling out clinically important traumatic brain injury (ciTBI) in the pediatric population under two years of age. In those over two, the rules had a 96.8% sensitivity and negative predictive value of 99.95% for ruling out ciTBI but had a 100% sensitivity in predicting those requiring neurosurgical intervention.[36][37][36] If any of the criteria are met, a CT scan of the brain may be warranted.

New Orleans Criteria

- Headache

- Vomiting (any)

- Age > 60 years

- Drug or alcohol intoxication

- Seizure

- Trauma visible above clavicles

- Short-term memory deficits

Canadian CT Head Injury/Trauma Rule

- Dangerous mechanism of injury (defined as a pedestrian struck by a motor vehicle, occupant ejected from a motor vehicle, or a fall from >3 feet or >5 stairs)

- Vomiting > than once

- Age > 65 years

- GCS score < 15, 2 hours post-injury

- Seizure after injury

- Any sign of basal skull fracture

- Possible open or depressed skull fracture

- Amnesia for events 30 minutes before injury

For pediatric patients (<16) at low risk for intracranial injuries, the best decision tool to determine the recommendation of the CT scan is the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) head trauma algorithm, which is based on a large-scale clinical trial of the same name and has had repeated external validation.[38][36][38]

PECARN for children younger than 2 years old:

- Scalp hematomas (especially those that are not frontal)

- Loss of consciousness for 5 seconds or more

- Severe mechanism of injury (such as motor vehicle collision, fall from elevation greater than 3 feet, or being struck by a high-impact object)

- Abnormal behavior, according to the parents, and palpable skull fracture

PECARN for children 2 years old and older:

- Loss of consciousness

- Vomiting

- Severe headache

- Severe mechanism of injury

- Signs of basilar skull fracture

- Altered mental status

There are many other trauma rules that can help risk stratify and help guide on prognosis and testing. Many of them can be found at https://www.mdcalc.com/. Some other commonly used and studies rules include CRASH and IMPACT. The CRASH prognosis calculator predicts death at 14 days and death and severe disability at 6 months in adult patients with GCS 14 or less. It does not help determine whether or not a CT is necessary.[39] The IMPACT prognosis calculator predicts a 6-month outcome in adult patients with moderate to severe traumatic intracranial injury. It does not help determine whether or not a CT is necessary.[40]

Treatment / Management

The prime objective in the management of head trauma involves preventing secondary brain insults. The algorithm in the management involves:

- Securing airway and maintaining ventilation

- Maintaining adequate cerebral perfusion pressure

- Preventing hypoxia, hypotension, hypercapnia, or hypocapnia

- Evaluating and managing raised ICP

- Obtain urgent neurosurgical consultation for traumatic intracranial lesions

- Identifying and treating other life-threatening injuries or conditions [41][42][43] (A1)

Airway, Breathing, and Circulation

Identify any condition that might compromise the airway, such as a pneumothorax, hemothorax, or pulmonary contusion causing hypoxemia. For sedation, consider using short-acting agents that have a minimal effect on blood pressure or ICP (etomidate or propofol for induction and vecuronium or rocuronium for neuromuscular blockade). Consider endotracheal intubation in the following situations:

- Inadequate ventilation or gas exchange, such as hypercarbia, hypoxia, or apnea

- Severe head injury

- Inability to protect the airway

- Severely agitated patient

The cervical spine should be maintained in line during intubation. Nasotracheal intubation should be avoided in facial trauma or basilar skull fracture patients.

The targets should maintain oxygen saturation greater than 90%, PaO2 greater than 60 mm Hg, and PCO2 at 35 to 45 mm Hg.

Avoid hypotension. Normal blood pressure may not be adequate to maintain adequate flow and CPP if ICP is elevated. The target is maintaining systolic blood pressure greater than 90 mm Hg and MAP greater than 80 mm Hg. Isolated head trauma usually does not cause hypotension. If the patient is in hypovolemic shock, look for another cause.

Mild Head Trauma

Epidemiological data suggests that the majority of head trauma is mild. In this event, many of these patients can be discharged following a routine neurological examination as there is minimal risk of developing intracranial pathology. The utilization of the externally validated head injury trauma rules like the New Orleans Criteria and Canadian CT Head Injury rules can assist in this triage process on who will likely benefit from head imaging prior to discharge. If CT imaging is not available, one can consider observing for at least 4 to 6 hours if no imaging was obtained. One should consider hospitalization if any of these other risk factors are present:

- Bleeding disorder

- Patients taking anticoagulation therapy or antiplatelet therapy

- Previous neurosurgical procedure

It is imperative to provide strict return precautions for patients discharged without imaging. A study of metabolomics and microRNAs can help predict the need for a CT scan of the head among these cohorts.[21][44] Collaborative European NeuroTrauma Effectiveness Research in Traumatic Brain Injury (CENTER-TBI) compared six biomarkers (S100B, glial fibrillary acidic protein, ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1, neuron-specific enolase, neurofilament light, and total tau) with four clinical decision rules (the Canadian CT head rule, the CT in Head injury Patients, the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline for head injury, and New Orleans criteria).[21] The study revealed that Glial fibrillary acidic protein demonstrated superior performance compared to other biomarkers in distinguishing the necessity for CT scans among individuals with mild head injuries. It exhibited a 99% probability of more effectively identifying CT-positive patients than the clinical characteristics utilized in current decision-making frameworks.[21](B2)

Scandinavian Neurotrauma Committee advocates CT imaging among cohorts with minimal head injury presenting with the following clinical characteristics:

- Loss of consciousness and repeated vomiting alongside increased S100B assay

- Seizures, neurological deficits, and clinical evidence of depressed or skull base fractures

- Patients on therapeutic anticoagulation or having bleeding disorders

- Age >65 years and on antiplatelet medications

- This minimizes health costs, radiation hazards, and emergency overcrowding without compromising patients' safety.[45]

Moderate to Severe Head Trauma

Prehospital and ED care should prioritize on:

- Stabilization of physiological parameters as per the principles of Advanced Trauma Life Support

- Rapid correction of impaired coagulation

- Noninvasive techniques to monitor ICP

- Emergent surgical evacuation of mass lesions or decompressive craniectomy and

- Temporary measures to counteract ICP [46] (B3)

Current recommendations include:

- Optimizing Oxygenation (SpO2 >90%), blood pressure (SBP >110 mm Hg), and maintaining euthermia. Prehospital guidelines of the Brain Trauma Foundation recommend intubation with a GCS of 8 or less, while the CENTER-TBI advocates in-hospital intubation with a GCS of 10 or lower.[21] Maintaining euthermia may help prevent coagulopathy and infection associated with hypothermia, as well as increased metabolic demand and energy failure associated with hyperthermia.

- Supplemental oxygen to all patients in the prehospital environment

- Maintain end-tidal CO2 reading between 35 to 45 mm Hg

- Pupil and GCS assessment every 30 mins

- Prophylactic administration of hyperosmolar therapy in the absence of signs of herniation and prehospital tranexamic acid is discouraged.[47]

The central dogma in managing raised ICP is preventing secondary insults. Ventricular catheters represent a "global" ICP and are the gold standard.[26] Parenchymal monitors, though easier to insert in cases of midline shift or malignant brain swelling, cannot be recalibrated in vivo, only measure a localized pressure, and have a high propensity for drift issues in long-term usage. The current noninvasive techniques such as pulsatility index from transcranial doppler, tympanic membrane displacement (otoacoustic emissions), near-infrared spectroscopy, and optic nerve sheath diameter assessments are not accurate enough to replace traditional invasive techniques and have significant inter-rater variability.[26]

Brain Trauma Foundation guidelines advocate ICP monitoring for cohorts with:

- Severe TBI (GCS of 3 to 8) with abnormal CT images or

- At least two criteria: age over 40 years, SBP <90 mm Hg, or abnormal posturing.[27]

Other ICP Monitoring Recommendations include:

- Patients with an initial normal CT scan or with minor changes in CT images but later show features of neurologic worsening or progression on the repeat scan

- Evidence of brain swelling (eg, compressed or absent basal cisterns)

- Extensive bifrontal contusions independent of the neurological condition

- When sedation interruption to check neurological function is not justified (eg, respiratory failure from lung contusions and flail chest)

- When the neurological examination is not reliable (eg, maxillofacial trauma or spinal cord injury) [26]

World Society of Emergency Surgery strongly recommends following guidelines for the 'Hub and Spike' model of managing severe head injury:

- Telemedicine to facilitate the early transfer of radio images

- Hemodynamic stabilization before referral

- Clear therapeutic communications and collaborations between personnel at the multispeciality level

- Transfer via trained and certified health team with serial neurological monitoring (check only pupils without interrupting sedation among cohorts with features of raised intracranial pressure)

- Pupillpmetry study or ocular ultrasound study for optic nerve sheath diameter assessment should not unnecessarily delay the transfer of patients.

- The patient should be sedated, intubated, and on mechanical ventilation during transfer, with the head of the bed elevated to 30° to 45°

- Provision of cardiorespiratory and invasive BP monitoring, keeping SBP >110 mm Hg and MAP >90 mm Hg

- Platelet count >75.000/mm3, PT/aPTT <1.5

- Aim for normothermia, Hemoglobin level >7 g/dL, SpO2 >94%, PaCO2 of 35 to 38 mm Hg, serum Na 140 to 145 mEq/L

- Increased sedation, osmotherapy, and short-term hyperventilation are justified for patients with brain herniation awaiting emergent neurosurgery [48] (B3)

Proposed tiers in the management of refractory intracranial hypertension include:

- Evacuation of hematoma harbingering or causing cerebral herniation

- Physiological neuroprotection

- Sedation, analgesics, and ventilation

- CSF drainage

- Osmotherapy with mannitol or hypertonic saline

- Hyperventilation

- Hypothermia

- Barbiturate coma

- Decompressive hemicraniectomy [27]

Differential Diagnosis

Primary Brain Injuries

- Concussion

- Contusion

- Diffuse Axonal Injury (DAI)

- Epidural Hematoma

- Subdural Hematoma

- Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage

- Traumatic Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Secondary Brain Injuries

- Cerebral Edema

- Ischemia/Stroke

- Infection (eg, meningitis, ventriculitis)

- Hypoxic-Anoxic Injury

Other Injuries and Conditions

- Skull Fractures

- Cervical Spine Injuries

- Post-Concussion Syndrome

- Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE)

- Second Impact Syndrome

- Psychiatric Conditions (eg, PTSD, adjustment disorders)

Prognosis

The outcomes after head trauma depend on a multitude of factors. These include the patient's age, the initial Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, the presence of anisocoria, the time to onset of herniation symptoms, the presence of associated polytrauma, concurrent conditions such as hypoxia or hypotension, the type of lesion (whether extradural or subdural hemorrhage), and the Marshall and Rotterdam CT scores.[27] Notably, the post-resuscitation GCS score is a critical determinant of outcome, with patients presenting a GCS of less than eight having a significantly higher mortality risk.

CT imaging of the brain is the gold standard in assessing and risk-stratifying those with TBI. There are two well-known scoring systems, Marshall and Rotterdam, that utilize imaging findings to help predict complications, mortality, and the need for neurosurgical intervention. The Marshall score was the first in 1991, followed by the Rotterdam score system in 2005. [49][50] The Rotterdam score uses the presence of epidural lesions, intraventricular blood, and subarachnoid hemorrhage for scoring and outperforms the Marshall score utilizing the following components: intraventricular blood or subarachnoid hemorrhage is graded as 0 (absent) or 1 (present), the basal cistern is graded as 0 (normal), 1 (compressed), or 2 (absent), the epidural mass lesion is graded as 0 (absent) or 1 (present), and the midline shift is graded as 0 (no shift or shift < 5mm) or 1 (shift > 5mm). Those with a score of 1 have been found to have lower mortality, 3.2%, while those with a score of 6 can have mortalities of almost 80%.[51]

Research studies such as the International Mission for Prognosis And Clinical Trial (IMPACT), TRACK-TBI, and CENTER-TBI have developed prognostic scoring systems to aid outcome prediction.[6][52] Interestingly, genomics plays a role in head trauma outcomes, with approximately 25% of the variance attributed to genetic factors.[21]

Advancements in patient management now include the monitoring of partial pressure of brain tissue oxygen (PbtO2) and cerebral metabolism through microdialysis, alongside focused management of intracranial pressure (ICP) and cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP).[53] The importance of early and continuous rehabilitation in improving long-term clinical outcomes cannot be overstated, emphasizing the need for a holistic and interdisciplinary approach to precision medicine.[21] Additionally, machine learning is emerging as a valuable tool in predicting adverse outcomes and mortality.[54][55][56]

For mild traumatic brain injury(concussion), potential physical sequelae include postconcussive syndrome, which is thought to occur in 80% of patients; second impact syndrome, a rare disorder that results in rapid cerebral edema and high mortality; posttraumatic epilepsy; and chronic traumatic encephalopathy. In those suffering from sports-related mild TBI (concussion), most symptoms (>70%) resolve within three days to two weeks, with the rest improving within four weeks.[57][58] Although adolescent females have a higher incidence rate and risk of injury from sport-related concussions, adolescent females and males usually recover at the same rate following TBI. It has been noted in some reports that females report more neurobehavioral and somatic symptoms, and males report more cognitive symptoms like confusion and amnesia.[57][59][60] The assessment of adolescents and those playing sports following a concussion should follow a physician-directed return-to-play progression prior to returning to sport. These guidelines and recommendations can be found through various consensus statements like that of the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine (AMSSM).[61] Following the completion of the six return-to-sport (RTS) strategy steps, with each step taking about 24 hours to complete, the medical determination to return to sport or at-risk activity can be concluded.

Complications

- Brain death

- Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (especially in military personnel and athletes related to contact sports) [62]

- CNS infection [63]

- CSF leaks [64]

- Dementia [65]

- Deep vein thrombosis

- Depression and PTSD [66]

- Dyselectrolytemia (eg, cerebral salt wasting and SIADH) [67][68][67]

- Endocrinopathies such as hypopituitarism [69]

- Hydrocephalus

- Malignant cerebral edema

- Neurogenic pulmonary edema [70]

- Neurovascular injuries

- Paroxysmal sympathetic hyperactivity [71]

- Pneumocephalus [72]

- Seizures

- Spasticity [73]

- Stunned myocardium syndrome [74]

- Substance use disorder

- Vasospasm [75]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Prevention is critical, as most cases of traumatic brain injury are due to accidents from preventable trauma. Motor vehicle collisions, the most common cause of TBI, are not always preventable. However, some measures can be taken to decrease risk, including wearing a seatbelt, not driving while distracted or under the influence of drugs or alcohol, and using appropriate booster seats for children based on age. Bicyclists and motorcyclists should be encouraged to wear helmets. There is active research on recurrent traumatic brain injuries in sports. In a patient who has already experienced brain trauma, it is important to not return to activities until they have improved. Recurrent brain trauma may put patients at risk of lifelong symptoms, and there may be cumulative and permanent effects.

In patients who have already experienced an injury, posttrauma recovery is a challenging process of physical, mental, and emotional recovery. Neurologic and psychiatric complications are common. Suicide prevention in patients who have experienced brain trauma is also important, and patients should always be encouraged to seek help.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional team is crucial to successful treatment and rehabilitation of patients who have experienced traumatic brain injuries. Case managers or social workers can provide information regarding resources, coordinate appointments, assist with discharge planning, and work with insurance so that the patient may receive the care they need. Occupational therapists help in improving functional status and focus on activities of daily living, which may suffer severe limitations due to traumatic brain injuries; they may recommend alterations to the home to improve functional capacity. Physical therapists may recover strength, endurance, and coordination; they may also recommend using assistive devices and provide training on how to use them. Speech-language pathologists may evaluate and treat communication and swallowing difficulties.

The nursing staff is vital at every stage, from providing intensive monitoring and total medical care in an acute setting to educating patients in the longer term. Physiatrists may oversee the rehabilitation team and determine if a patient is appropriate for intensive rehabilitation programs. Primary care providers are essential in long-term follow-up and coordinating care in patients with brain trauma. Neurologists diagnose and treat conditions of the nervous system and may coordinate the care of brain trauma and long-term sequelae. Neurosurgeons determine the need for surgical intervention and perform such interventions as indicated. Neuropsychologists may conduct more extensive cognitive testing and aid in assessing the patient's ability to manage their financial, legal, and medical decisions. If any pharmaceutical therapy plays a role in management, pharmacists are vital to evaluating dosing, drug interactions, and counsel regarding potential adverse effects.

A coordinated interprofessional team effort is essential in the diagnosis and management of brain trauma injuries, and only through this approach can patient outcomes achieve their optimal results.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

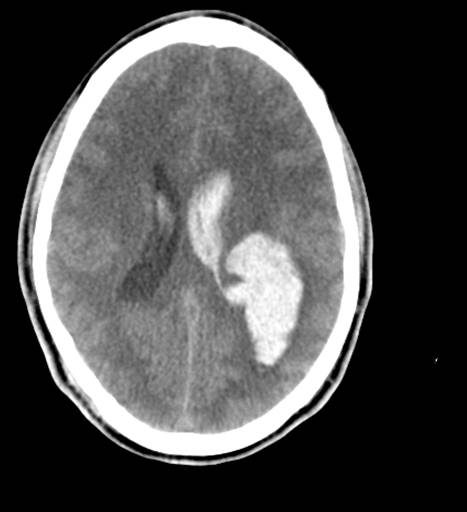

Brain Trauma Computed Tomography. This image shows a preoperative computed tomography (CT) scan of a patient with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 14. The article reads, "Emergent CT imaging revealed a sagittally oriented skull fracture extending from the vertex to the foramen magnum as well as a transverse parietal and temporal bone fracture. Multiple frontal, parietal, and temporal lobe contusions with associated interhemispheric hemorrhage and a left-sided subdural hematoma measuring 1.7 mm in greatest depth were appreciated. Effacement of the basilar cisterns was noted without shift of midline structures."

Contributed by Wikimedia Commons, Rehman T, Ali R, Tawil I, Yonas H (CC by 2.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.es

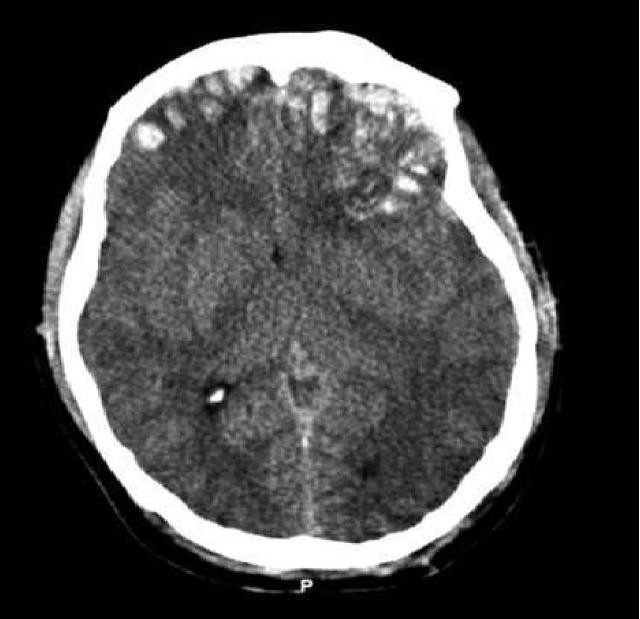

(Click Image to Enlarge)

3D reconstructed DTI image on the left demonstrates marked bilateral frontal axonal thinning and fiber tract gaps in this patient with bilateral post-traumatic frontal contusions on conventional imaging. The image on right is a normal 3D DTI. Contributed by Travis Snyder DO, SimonMed Centers Las Vegas NV

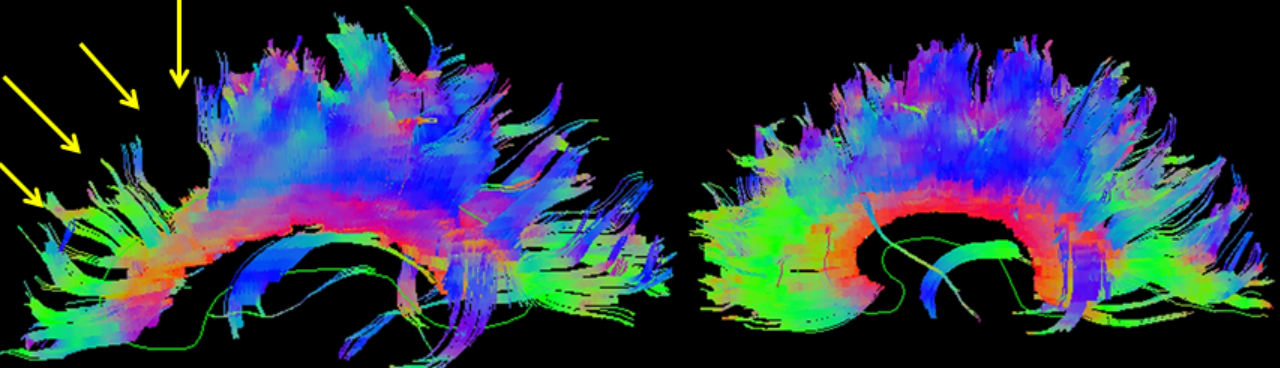

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Original description: Figure 2. CT and enhanced gradient echo T2 star-weighted angiography (ESWAN) images of the brain of a 54-year-old man who experienced a traumatic brain injury. An axial head CT image displays right frontotemporal SAH (Fisher grade 4) with bilateral frontal contusions and intracerebral hematoma (A). A follow-up CT image 26 weeks after the brain injury indicates that the hemorrhages were completely resolved and the lateral ventricles were mildly enlarged (B). A follow-up MRI (1.5T) image was obtained 26 weeks following the head injury (C,D). The axial ESWAN image displays a rim of hypointensity (arrowheads), with hemosiderin deposits forming along the cerebral convexity (C, D). Contributed by Hongwei Zhao, Jin Wang, Zhonglie Lu, Qingjie Wu, Haijuan Lv, Hu Liu, Xiangyang Gong

References

Li Q, Wang P, Huang C, Chen B, Liu J, Zhao M, Zhao J. N-Acetyl Serotonin Protects Neural Progenitor Cells Against Oxidative Stress-Induced Apoptosis and Improves Neurogenesis in Adult Mouse Hippocampus Following Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of molecular neuroscience : MN. 2019 Apr:67(4):574-588. doi: 10.1007/s12031-019-01263-6. Epub 2019 Jan 25 [PubMed PMID: 30684239]

Glynn N, Agha A. The frequency and the diagnosis of pituitary dysfunction after traumatic brain injury. Pituitary. 2019 Jun:22(3):249-260. doi: 10.1007/s11102-019-00938-y. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30684166]

Rodríguez-Triviño CY, Torres Castro I, Dueñas Z. Hypochloremia in Patients with Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: A Possible Risk Factor for Increased Mortality. World neurosurgery. 2019 Apr:124():e783-e788. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.01.025. Epub 2019 Jan 22 [PubMed PMID: 30682506]

Keelan RE, Mahoney EJ, Sherer M, Hart T, Giacino J, Bodien YG, Nakase-Richardson R, Dams-O'Connor K, Novack TA, Vanderploeg RD. Neuropsychological Characteristics of the Confusional State Following Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society : JINS. 2019 Mar:25(3):302-313. doi: 10.1017/S1355617718001157. Epub 2019 Jan 25 [PubMed PMID: 30681046]

Menon DK, Schwab K, Wright DW, Maas AI, Demographics and Clinical Assessment Working Group of the International and Interagency Initiative toward Common Data Elements for Research on Traumatic Brain Injury and Psychological Health. Position statement: definition of traumatic brain injury. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2010 Nov:91(11):1637-40. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.05.017. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21044706]

Wilson MH, Ashworth E, Hutchinson PJ, British Neurotrauma Group. A proposed novel traumatic brain injury classification system - an overview and inter-rater reliability validation on behalf of the Society of British Neurological Surgeons. British journal of neurosurgery. 2022 Oct:36(5):633-638. doi: 10.1080/02688697.2022.2090509. Epub 2022 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 35770478]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLamb LC, DiFiori M, Comey C, Feeney J. Cost Analysis of Direct Oral Anticoagulants Compared with Warfarin in Patients with Blunt Traumatic Intracranial Hemorrhages. The American surgeon. 2018 Jun 1:84(6):1010-1014 [PubMed PMID: 29981640]

Daher P, Teixeira PG, Coopwood TB, Brown LH, Ali S, Aydelotte JD, Ford BJ, Hensely AS, Brown CV. Mild to Moderate to Severe: What Drives the Severity of ARDS in Trauma Patients? The American surgeon. 2018 Jun 1:84(6):808-812 [PubMed PMID: 29981606]

Harvell BJ, Helmer SD, Ward JG, Ablah E, Grundmeyer R, Haan JM. Head CT Guidelines Following Concussion among the Youngest Trauma Patients: Can We Limit Radiation Exposure Following Traumatic Brain Injury? Kansas journal of medicine. 2018 May:11(2):1-17 [PubMed PMID: 29796153]

Stein TD, Alvarez VE, McKee AC. Concussion in Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. Current pain and headache reports. 2015 Oct:19(10):47. doi: 10.1007/s11916-015-0522-z. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26260277]

Mesfin FB, Gupta N, Hays Shapshak A, Taylor RS. Diffuse Axonal Injury. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28846342]

Laskowitz D, Grant G, Su E, Bell M. Diffuse Axonal Injury. Translational Research in Traumatic Brain Injury. 2016:(): [PubMed PMID: 26583181]

Portaro S, Naro A, Cimino V, Maresca G, Corallo F, Morabito R, Calabrò RS. Risk factors of transient global amnesia: Three case reports. Medicine. 2018 Oct:97(41):e12723. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012723. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30313071]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSalehpour F, Bazzazi AM, Aghazadeh J, Hasanloei AV, Pasban K, Mirzaei F, Naseri Alavi SA. What do You Expect from Patients with Severe Head Trauma? Asian journal of neurosurgery. 2018 Jul-Sep:13(3):660-663. doi: 10.4103/ajns.AJNS_260_16. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30283522]

Bushnik T, Hanks RA, Kreutzer J, Rosenthal M. Etiology of traumatic brain injury: characterization of differential outcomes up to 1 year postinjury. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2003 Feb:84(2):255-62 [PubMed PMID: 12601658]

Alao T, Munakomi S, Waseem M. Penetrating Head Trauma. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083824]

Dewan MC, Rattani A, Gupta S, Baticulon RE, Hung YC, Punchak M, Agrawal A, Adeleye AO, Shrime MG, Rubiano AM, Rosenfeld JV, Park KB. Estimating the global incidence of traumatic brain injury. Journal of neurosurgery. 2019 Apr 1:130(4):1080-1097. doi: 10.3171/2017.10.JNS17352. Epub 2018 Apr 27 [PubMed PMID: 29701556]

Mohammadifard M, Ghaemi K, Hanif H, Sharifzadeh G, Haghparast M. Marshall and Rotterdam Computed Tomography scores in predicting early deaths after brain trauma. European journal of translational myology. 2018 Jul 10:28(3):7542. doi: 10.4081/ejtm.2018.7542. Epub 2018 Jul 16 [PubMed PMID: 30344974]

Lalwani S, Hasan F, Khurana S, Mathur P. Epidemiological trends of fatal pediatric trauma: A single-center study. Medicine. 2018 Sep:97(39):e12280. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012280. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30278499]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSchneider ALC, Wang D, Ling G, Gottesman RF, Selvin E. Prevalence of Self-Reported Head Injury in the United States. The New England journal of medicine. 2018 Sep 20:379(12):1176-1178. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1808550. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30231228]

Maas AIR, Menon DK, Manley GT, Abrams M, Åkerlund C, Andelic N, Aries M, Bashford T, Bell MJ, Bodien YG, Brett BL, Büki A, Chesnut RM, Citerio G, Clark D, Clasby B, Cooper DJ, Czeiter E, Czosnyka M, Dams-O'Connor K, De Keyser V, Diaz-Arrastia R, Ercole A, van Essen TA, Falvey É, Ferguson AR, Figaji A, Fitzgerald M, Foreman B, Gantner D, Gao G, Giacino J, Gravesteijn B, Guiza F, Gupta D, Gurnell M, Haagsma JA, Hammond FM, Hawryluk G, Hutchinson P, van der Jagt M, Jain S, Jain S, Jiang JY, Kent H, Kolias A, Kompanje EJO, Lecky F, Lingsma HF, Maegele M, Majdan M, Markowitz A, McCrea M, Meyfroidt G, Mikolić A, Mondello S, Mukherjee P, Nelson D, Nelson LD, Newcombe V, Okonkwo D, Orešič M, Peul W, Pisică D, Polinder S, Ponsford J, Puybasset L, Raj R, Robba C, Røe C, Rosand J, Schueler P, Sharp DJ, Smielewski P, Stein MB, von Steinbüchel N, Stewart W, Steyerberg EW, Stocchetti N, Temkin N, Tenovuo O, Theadom A, Thomas I, Espin AT, Turgeon AF, Unterberg A, Van Praag D, van Veen E, Verheyden J, Vyvere TV, Wang KKW, Wiegers EJA, Williams WH, Wilson L, Wisniewski SR, Younsi A, Yue JK, Yuh EL, Zeiler FA, Zeldovich M, Zemek R, InTBIR Participants and Investigators. Traumatic brain injury: progress and challenges in prevention, clinical care, and research. The Lancet. Neurology. 2022 Nov:21(11):1004-1060. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00309-X. Epub 2022 Sep 29 [PubMed PMID: 36183712]

GBD 2016 Traumatic Brain Injury and Spinal Cord Injury Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet. Neurology. 2019 Jan:18(1):56-87. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30415-0. Epub 2018 Nov 26 [PubMed PMID: 30497965]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSchimmel SJ, Acosta S, Lozano D. Neuroinflammation in traumatic brain injury: A chronic response to an acute injury. Brain circulation. 2017 Jul-Sep:3(3):135-142. doi: 10.4103/bc.bc_18_17. Epub 2017 Oct 12 [PubMed PMID: 30276315]

Ng SY, Lee AYW. Traumatic Brain Injuries: Pathophysiology and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience. 2019:13():528. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2019.00528. Epub 2019 Nov 27 [PubMed PMID: 31827423]

Munakomi S, Cherian I. Newer insights to pathogenesis of traumatic brain injury. Asian journal of neurosurgery. 2017 Jul-Sep:12(3):362-364. doi: 10.4103/1793-5482.180882. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28761509]

Munakomi S, Das JM. Intracranial Pressure Monitoring. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31194438]

Munakomi S, Das JM. Brain Herniation. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31194403]

Sternbach GL. The Glasgow coma scale. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2000 Jul:19(1):67-71 [PubMed PMID: 10863122]

Das JM, Munakomi S. Raccoon Sign. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31194384]

Janas AM, Qin F, Hamilton S, Jiang B, Baier N, Wintermark M, Threlkeld Z, Lee S. Diffuse Axonal Injury Grade on Early MRI is Associated with Worse Outcome in Children with Moderate-Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. Neurocritical care. 2022 Apr:36(2):492-503. doi: 10.1007/s12028-021-01336-8. Epub 2021 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 34462880]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePavlović T, Milošević M, Trtica S, Budinčević H. Value of Head CT Scan in the Emergency Department in Patients with Vertigo without Focal Neurological Abnormalities. Open access Macedonian journal of medical sciences. 2018 Sep 25:6(9):1664-1667. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2018.340. Epub 2018 Sep 24 [PubMed PMID: 30337984]

Hajiaghamemar M, Lan IS, Christian CW, Coats B, Margulies SS. Infant skull fracture risk for low height falls. International journal of legal medicine. 2019 May:133(3):847-862. doi: 10.1007/s00414-018-1918-1. Epub 2018 Sep 7 [PubMed PMID: 30194647]

Stiell IG, Wells GA, Vandemheen K, Clement C, Lesiuk H, Laupacis A, McKnight RD, Verbeek R, Brison R, Cass D, Eisenhauer ME, Greenberg G, Worthington J. The Canadian CT Head Rule for patients with minor head injury. Lancet (London, England). 2001 May 5:357(9266):1391-6 [PubMed PMID: 11356436]

Stiell IG, Clement CM, Rowe BH, Schull MJ, Brison R, Cass D, Eisenhauer MA, McKnight RD, Bandiera G, Holroyd B, Lee JS, Dreyer J, Worthington JR, Reardon M, Greenberg G, Lesiuk H, MacPhail I, Wells GA. Comparison of the Canadian CT Head Rule and the New Orleans Criteria in patients with minor head injury. JAMA. 2005 Sep 28:294(12):1511-8 [PubMed PMID: 16189364]

Haydel MJ, Preston CA, Mills TJ, Luber S, Blaudeau E, DeBlieux PM. Indications for computed tomography in patients with minor head injury. The New England journal of medicine. 2000 Jul 13:343(2):100-5 [PubMed PMID: 10891517]

Kuppermann N, Holmes JF, Dayan PS, Hoyle JD Jr, Atabaki SM, Holubkov R, Nadel FM, Monroe D, Stanley RM, Borgialli DA, Badawy MK, Schunk JE, Quayle KS, Mahajan P, Lichenstein R, Lillis KA, Tunik MG, Jacobs ES, Callahan JM, Gorelick MH, Glass TF, Lee LK, Bachman MC, Cooper A, Powell EC, Gerardi MJ, Melville KA, Muizelaar JP, Wisner DH, Zuspan SJ, Dean JM, Wootton-Gorges SL, Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN). Identification of children at very low risk of clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort study. Lancet (London, England). 2009 Oct 3:374(9696):1160-70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61558-0. Epub 2009 Sep 14 [PubMed PMID: 19758692]

Schonfeld D, Bressan S, Da Dalt L, Henien MN, Winnett JA, Nigrovic LE. Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network head injury clinical prediction rules are reliable in practice. Archives of disease in childhood. 2014 May:99(5):427-31. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-305004. Epub 2014 Jan 15 [PubMed PMID: 24431418]

Prince C, Bruhns ME. Evaluation and Treatment of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: The Role of Neuropsychology. Brain sciences. 2017 Aug 17:7(8):. doi: 10.3390/brainsci7080105. Epub 2017 Aug 17 [PubMed PMID: 28817065]

Olivecrona M, Olivecrona Z. Use of the CRASH study prognosis calculator in patients with severe traumatic brain injury treated with an intracranial pressure-targeted therapy. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 2013 Jul:20(7):996-1001. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2012.09.015. Epub 2013 May 20 [PubMed PMID: 23702375]

Olivecrona M, Koskinen LO. The IMPACT prognosis calculator used in patients with severe traumatic brain injury treated with an ICP-targeted therapy. Acta neurochirurgica. 2012 Sep:154(9):1567-73. doi: 10.1007/s00701-012-1351-z. Epub 2012 Apr 29 [PubMed PMID: 22543506]

Brommeland T, Helseth E, Aarhus M, Moen KG, Dyrskog S, Bergholt B, Olivecrona Z, Jeppesen E. Best practice guidelines for blunt cerebrovascular injury (BCVI). Scandinavian journal of trauma, resuscitation and emergency medicine. 2018 Oct 29:26(1):90. doi: 10.1186/s13049-018-0559-1. Epub 2018 Oct 29 [PubMed PMID: 30373641]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJacquet C, Boetto S, Sevely A, Sol JC, Chaix Y, Cheuret E. Monitoring Criteria of Intracranial Lesions in Children Post Mild or Moderate Head Trauma. Neuropediatrics. 2018 Dec:49(6):385-391. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1668138. Epub 2018 Sep 17 [PubMed PMID: 30223286]

Bayley MT, Lamontagne ME, Kua A, Marshall S, Marier-Deschênes P, Allaire AS, Kagan C, Truchon C, Janzen S, Teasell R, Swaine B. Unique Features of the INESSS-ONF Rehabilitation Guidelines for Moderate to Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: Responding to Users' Needs. The Journal of head trauma rehabilitation. 2018 Sep/Oct:33(5):296-305. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000428. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30188459]

Fedoruk RP, Lee CH, Banoei MM, Winston BW. Metabolomics in severe traumatic brain injury: a scoping review. BMC neuroscience. 2023 Oct 16:24(1):54. doi: 10.1186/s12868-023-00824-1. Epub 2023 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 37845610]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceVedin T, Karlsson M, Edelhamre M, Clausen L, Svensson S, Bergenheim M, Larsson PA. A proposed amendment to the current guidelines for mild traumatic brain injury: reducing computerized tomographies while maintaining safety. European journal of trauma and emergency surgery : official publication of the European Trauma Society. 2021 Oct:47(5):1451-1459. doi: 10.1007/s00068-019-01145-x. Epub 2019 May 14 [PubMed PMID: 31089789]

Hossain I, Rostami E, Marklund N. The management of severe traumatic brain injury in the initial postinjury hours - current evidence and controversies. Current opinion in critical care. 2023 Dec 1:29(6):650-658. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000001094. Epub 2023 Oct 11 [PubMed PMID: 37851061]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHawryluk GWJ, Lulla A, Bell R, Jagoda A, Mangat HS, Bobrow BJ, Ghajar J. Guidelines for Prehospital Management of Traumatic Brain Injury 3rd Edition: Executive Summary. Neurosurgery. 2023 Dec 1:93(6):e159-e169. doi: 10.1227/neu.0000000000002672. Epub 2023 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 37750693]

Picetti E, Catena F, Abu-Zidan F, Ansaloni L, Armonda RA, Bala M, Balogh ZJ, Bertuccio A, Biffl WL, Bouzat P, Buki A, Cerasti D, Chesnut RM, Citerio G, Coccolini F, Coimbra R, Coniglio C, Fainardi E, Gupta D, Gurney JM, Hawryluk GWJ, Helbok R, Hutchinson PJA, Iaccarino C, Kolias A, Maier RW, Martin MJ, Meyfroidt G, Okonkwo DO, Rasulo F, Rizoli S, Rubiano A, Sahuquillo J, Sams VG, Servadei F, Sharma D, Shutter L, Stahel PF, Taccone FS, Udy A, Zoerle T, Agnoletti V, Bravi F, De Simone B, Kluger Y, Martino C, Moore EE, Sartelli M, Weber D, Robba C. Early management of isolated severe traumatic brain injury patients in a hospital without neurosurgical capabilities: a consensus and clinical recommendations of the World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES). World journal of emergency surgery : WJES. 2023 Jan 9:18(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s13017-022-00468-2. Epub 2023 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 36624517]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMarshall LF, Marshall SB, Klauber MR, Van Berkum Clark M, Eisenberg H, Jane JA, Luerssen TG, Marmarou A, Foulkes MA. The diagnosis of head injury requires a classification based on computed axial tomography. Journal of neurotrauma. 1992 Mar:9 Suppl 1():S287-92 [PubMed PMID: 1588618]

Maas AI, Hukkelhoven CW, Marshall LF, Steyerberg EW. Prediction of outcome in traumatic brain injury with computed tomographic characteristics: a comparison between the computed tomographic classification and combinations of computed tomographic predictors. Neurosurgery. 2005 Dec:57(6):1173-82; discussion 1173-82 [PubMed PMID: 16331165]

Javeed F, Rehman L, Masroor M, Khan M. The Prediction of Outcomes in Patients Admitted With Traumatic Brain Injury Using the Rotterdam Score. Cureus. 2022 Sep:14(9):e29787. doi: 10.7759/cureus.29787. Epub 2022 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 36340537]

Steyerberg EW, Mushkudiani N, Perel P, Butcher I, Lu J, McHugh GS, Murray GD, Marmarou A, Roberts I, Habbema JD, Maas AI. Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: development and international validation of prognostic scores based on admission characteristics. PLoS medicine. 2008 Aug 5:5(8):e165; discussion e165. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050165. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18684008]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceStein KY, Froese L, Sekhon M, Griesdale D, Thelin EP, Raj R, Tas J, Aries M, Gallagher C, Bernard F, Gomez A, Kramer AH, Zeiler FA. Intracranial Pressure-Derived Cerebrovascular Reactivity Indices and Their Critical Thresholds: A Canadian High Resolution-Traumatic Brain Injury Validation Study. Journal of neurotrauma. 2024 Apr:41(7-8):910-923. doi: 10.1089/neu.2023.0374. Epub 2023 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 37861325]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMekkodathil A, El-Menyar A, Naduvilekandy M, Rizoli S, Al-Thani H. Machine Learning Approach for the Prediction of In-Hospital Mortality in Traumatic Brain Injury Using Bio-Clinical Markers at Presentation to the Emergency Department. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2023 Aug 5:13(15):. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics13152605. Epub 2023 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 37568968]

Courville E, Kazim SF, Vellek J, Tarawneh O, Stack J, Roster K, Roy J, Schmidt M, Bowers C. Machine learning algorithms for predicting outcomes of traumatic brain injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgical neurology international. 2023:14():262. doi: 10.25259/SNI_312_2023. Epub 2023 Jul 28 [PubMed PMID: 37560584]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTerabe ML, Massago M, Iora PH, Hernandes Rocha TA, de Souza JVP, Huo L, Massago M, Senda DM, Kobayashi EM, Vissoci JR, Staton CA, de Andrade L. Applicability of machine learning technique in the screening of patients with mild traumatic brain injury. PloS one. 2023:18(8):e0290721. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0290721. Epub 2023 Aug 24 [PubMed PMID: 37616279]

Frommer LJ, Gurka KK, Cross KM, Ingersoll CD, Comstock RD, Saliba SA. Sex differences in concussion symptoms of high school athletes. Journal of athletic training. 2011 Jan-Feb:46(1):76-84. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.1.76. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21214354]

Eisenberg MA, Meehan WP 3rd, Mannix R. Duration and course of post-concussive symptoms. Pediatrics. 2014 Jun:133(6):999-1006. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0158. Epub 2014 May 12 [PubMed PMID: 24819569]

Gessel LM, Fields SK, Collins CL, Dick RW, Comstock RD. Concussions among United States high school and collegiate athletes. Journal of athletic training. 2007 Oct-Dec:42(4):495-503 [PubMed PMID: 18174937]

Covassin T, Swanik CB, Sachs ML. Sex Differences and the Incidence of Concussions Among Collegiate Athletes. Journal of athletic training. 2003 Sep:38(3):238-244 [PubMed PMID: 14608434]

Patricios JS, Schneider KJ, Dvorak J, Ahmed OH, Blauwet C, Cantu RC, Davis GA, Echemendia RJ, Makdissi M, McNamee M, Broglio S, Emery CA, Feddermann-Demont N, Fuller GW, Giza CC, Guskiewicz KM, Hainline B, Iverson GL, Kutcher JS, Leddy JJ, Maddocks D, Manley G, McCrea M, Purcell LK, Putukian M, Sato H, Tuominen MP, Turner M, Yeates KO, Herring SA, Meeuwisse W. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 6th International Conference on Concussion in Sport-Amsterdam, October 2022. British journal of sports medicine. 2023 Jun:57(11):695-711. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2023-106898. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37316210]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMunakomi S, Puckett Y. Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31082057]

Zhao W, Guo S, Xu Z, Wang Y, Kou Y, Tian S, Qi Y, Pang J, Zhou W, Wang N, Liu J, Zhai Y, Ji P, Jiao Y, Fan C, Chao M, Fan Z, Qu Y, Wang L. Nomogram for Predicting Central Nervous System Infection Following Traumatic Brain Injury in the Elderly. World neurosurgery. 2024 Mar:183():e28-e43. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2023.10.088. Epub 2023 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 37879436]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOh JW, Kim SH, Whang K. Traumatic Cerebrospinal Fluid Leak: Diagnosis and Management. Korean journal of neurotrauma. 2017 Oct:13(2):63-67. doi: 10.13004/kjnt.2017.13.2.63. Epub 2017 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 29201836]

Graham NS, Sharp DJ. Dementia after traumatic brain injury. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2023 Oct 19:383():2065. doi: 10.1136/bmj.p2065. Epub 2023 Oct 19 [PubMed PMID: 37857435]

Carmichael J, Ponsford J, Gould KR, Spitz G. Characterizing depression after traumatic brain injury using a symptom-oriented approach. Journal of affective disorders. 2024 Jan 15:345():455-466. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.10.130. Epub 2023 Oct 24 [PubMed PMID: 37879410]

Leonard J, Garrett RE, Salottolo K, Slone DS, Mains CW, Carrick MM, Bar-Or D. Cerebral salt wasting after traumatic brain injury: a review of the literature. Scandinavian journal of trauma, resuscitation and emergency medicine. 2015 Nov 11:23():98. doi: 10.1186/s13049-015-0180-5. Epub 2015 Nov 11 [PubMed PMID: 26561391]

Chang CH, Liao JJ, Chuang CH, Lee CT. Recurrent hyponatremia after traumatic brain injury. The American journal of the medical sciences. 2008 May:335(5):390-3. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318149e6f1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18480658]

Tahara S, Otsuka F, Endo T. Recognition and Practice of Hypopituitarism After Traumatic Brain Injury and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage in Japan: A Survey. Neurology and therapy. 2024 Feb:13(1):39-51. doi: 10.1007/s40120-023-00553-x. Epub 2023 Oct 24 [PubMed PMID: 37874463]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAl-Dhahir MA, Das JM, Sharma S. Neurogenic Pulmonary Edema. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422579]

Salasky VR, Chowdhury SH, Chen LK, Almeida E, Kong X, Armahizer M, Pajoumand M, Schrank GM, Rabinowitz RP, Schwartzbauer G, Hu P, Badjatia N, Podell JE. Overlapping Physiologic Signs of Sepsis and Paroxysmal Sympathetic Hyperactivity After Traumatic Brain Injury: Exploring A Clinical Conundrum. Neurocritical care. 2024 Jun:40(3):1006-1012. doi: 10.1007/s12028-023-01862-7. Epub 2023 Oct 26 [PubMed PMID: 37884690]

Das JM, Munakomi S, Bajaj J. Pneumocephalus. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30571033]

Tani J, Wen YT, Hu CJ, Sung JY. Current and Potential Pharmacologic Therapies for Traumatic Brain Injury. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland). 2022 Jul 6:15(7):. doi: 10.3390/ph15070838. Epub 2022 Jul 6 [PubMed PMID: 35890136]

Kenigsberg BB, Barnett CF, Mai JC, Chang JJ. Neurogenic Stunned Myocardium in Severe Neurological Injury. Current neurology and neuroscience reports. 2019 Nov 13:19(11):90. doi: 10.1007/s11910-019-0999-7. Epub 2019 Nov 13 [PubMed PMID: 31720870]

Kramer DR, Winer JL, Pease BA, Amar AP, Mack WJ. Cerebral vasospasm in traumatic brain injury. Neurology research international. 2013:2013():415813. doi: 10.1155/2013/415813. Epub 2013 Jun 19 [PubMed PMID: 23862062]