Introduction

Right aortic arch anomalies occur in 0.01 to 0.1% of the general population. Abnormalities of aortic arch branching and orientation are associated with a variety of congenital heart defects (tetralogy of Fallot and truncus arteriosus), as well as chromosomal abnormalities, such as DiGeorge syndrome (22q11 deletion). While a right aortic arch with mirror image branching of the head and neck vessels does not cause any physiologic cardiovascular effects, a right aortic arch can be associated with other congenital heart defects. A subset of right aortic arches with certain nonmirror image branching patterns of the head and neck vessels can be associated with a vascular ring.[1][2] There are scenarios where the anatomic features of a right aortic are clinically relevant.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

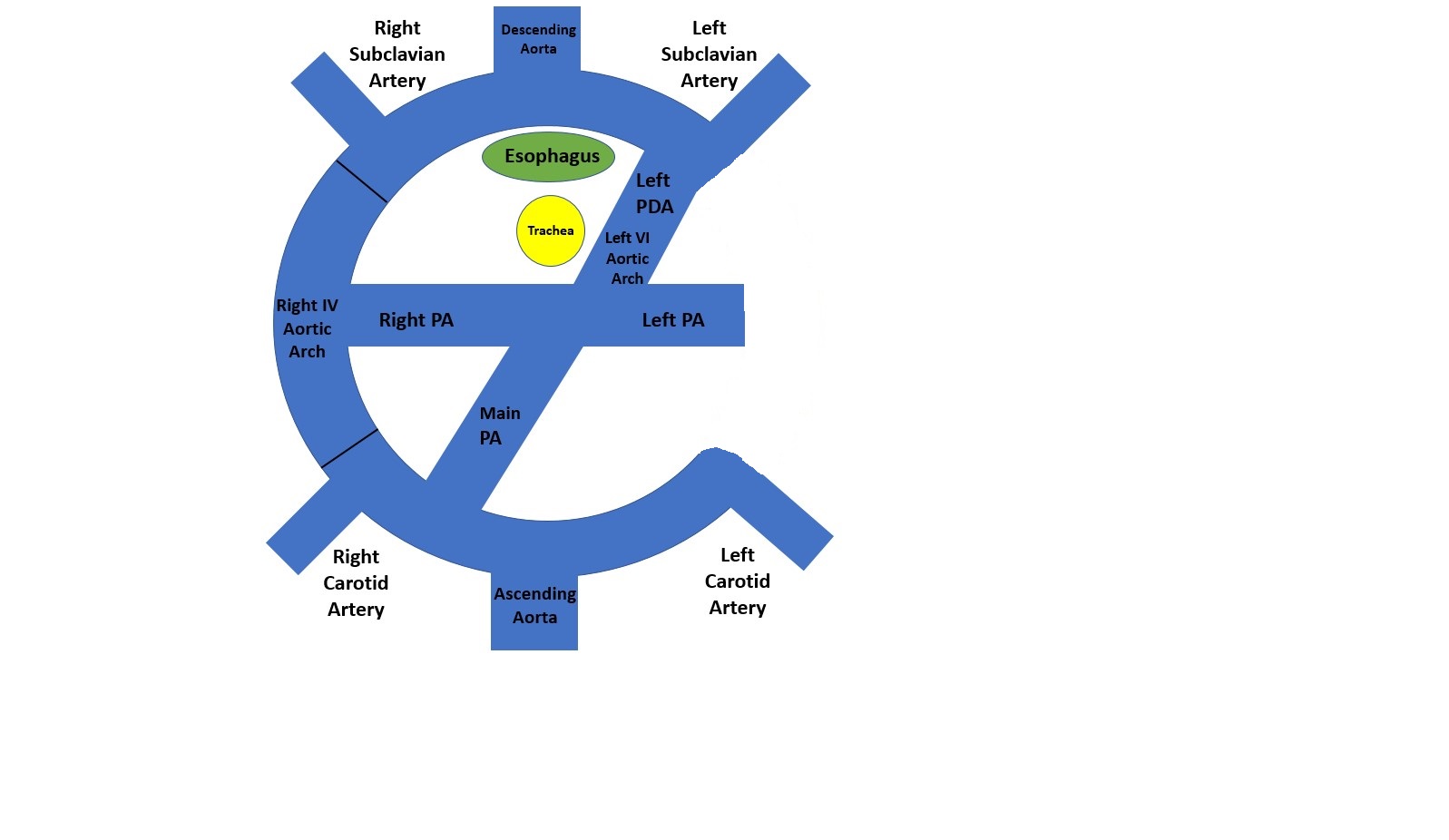

In many patients, no underlying genetic abnormality is identified in patients with a right aortic arch; however, a right aortic arch can be associated with Digeorge syndrome (22q11 deletion) as well as conotruncal congenital heart defects such as tetralogy of Fallot, truncus arteriosus, and d-transposition of the great arteries.[3][4][5] Generally, three types of aortic arches exist in the literature as defined by the Edwards classification scheme. [6] These types are as follows:

- Mirror image branching of the head and neck vessels. The first branch left the innominate artery, the second right carotid, and the third right subclavian.

- Most common (59%).

- Often associated with conotruncal congenital heart disease (truncus arteriosus and tetralogy of Fallot)

- Aberrant left subclavian artery from a diverticulum of Kommerell as a fourth branch from the aorta. The first branch is left carotid, second right carotid, and third right carotid.

- Second most common with a prevalence of approximately 40%.

- Not usually associated with congenital heart disease.

- Completes a vascular ring

- Obliteration/isolation of the left subclavian artery with collateralization. Otherwise, the arch branching is similar to type 2.

- Third most common with a prevalence of 1.5%.

Epidemiology

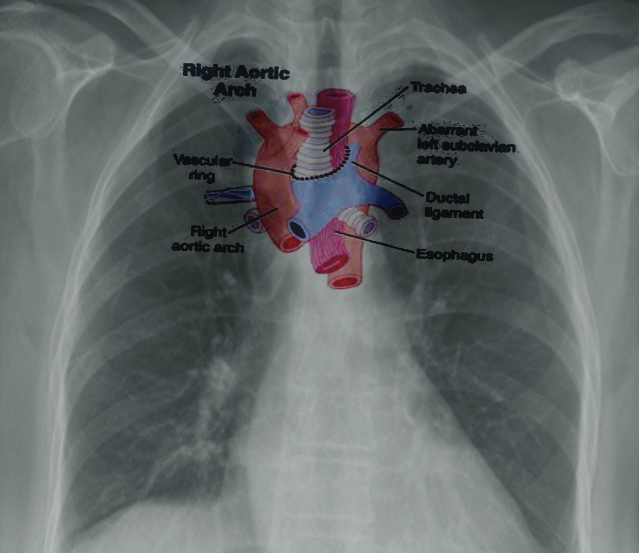

A right aortic arch occurs when the aortic arch traverses over the right bronchus instead of the left bronchus (which defines a left aortic arch). Embryologically, this develops when the right dorsal aorta persists and the left dorsal aorta regresses. Depending on the formation of the other branches of the aortic arch, various forms of the right aortic arch can develop. This includes a mirror type right aortic arch, defined by the first branch originating from the aorta being the left innominate artery, the second being the right common carotid artery, and the third being the right subclavian artery. This branching pattern is similar to the normal anatomical branching seen in the general population, however, in a mirror image. The ductus arteriosus in this scenario originates off the underside of the aortic arch or from the left innominate artery, which predisposes patients to left pulmonary artery stenosis or even isolation. In type 2 right-sided aortic arch, the first branch off the aorta is the left common carotid artery, followed by the left common carotid artery, right subclavian artery, and finally the left subclavian artery. If an aberrant left subclavian is present (type 2 aortic arch), the ductus arteriosus originates from this subclavian artery, which leads to an outpouching of the aorta (diverticulum of Kommerell). After the closure of the ductus arteriosus connection to the left pulmonary artery, and due to a retroesophageal course of the left subclavian artery, a vascular ring circumscribing the esophagus, causing am esophageal stricture. An extremely rare form of a right aortic arch with isolation of the left subclavian from a ductal attachment to the left pulmonary artery can occur. Rarely, a double aortic arch with an atretic left segment can be misdiagnosed as a right aortic arch. This differentiation is very important as the expected symptomatology, and surgical treatment are different.[7][8][9][2]

Pathophysiology

The right aortic arch with mirror image branching does not cause any cardiovascular, airway, or swallowing symptoms. It can be associated with left pulmonary artery flow abnormalities, especially if a left ductus from the innominate artery was present. Right aortic arch with an aberrant left subclavian causes a vascular ring can be associated with swallowing difficulties (dysphagia lusoria) in children after they begin to eat solid foods, especially meat. Rarely, it can be associated with stridor and recurrent croup if there are compression and malacia of the trachea; however, this symptomatology is more common in double aortic arches.[10][11]

History and Physical

History and physical examination show abnormalities associated with an underlying intracardiac congenital heart defect such as tetralogy of Fallot or truncus arteriosus. Without an underlying intracardiac congenital heart defect, the cardiac physical examination in a patient with a right aortic arch is normal. Symptoms of a vascular ring include a history of recurrent croup and an examination finding of stridor, more often noted in double aortic arch forms of vascular rings. The history of dysphagia is a more common finding in the right aortic arch and aberrant left subclavian form of a vascular ring. In "loose vascular rings," the patient could remain asymptomatic over their lifetime.[10][11]

Evaluation

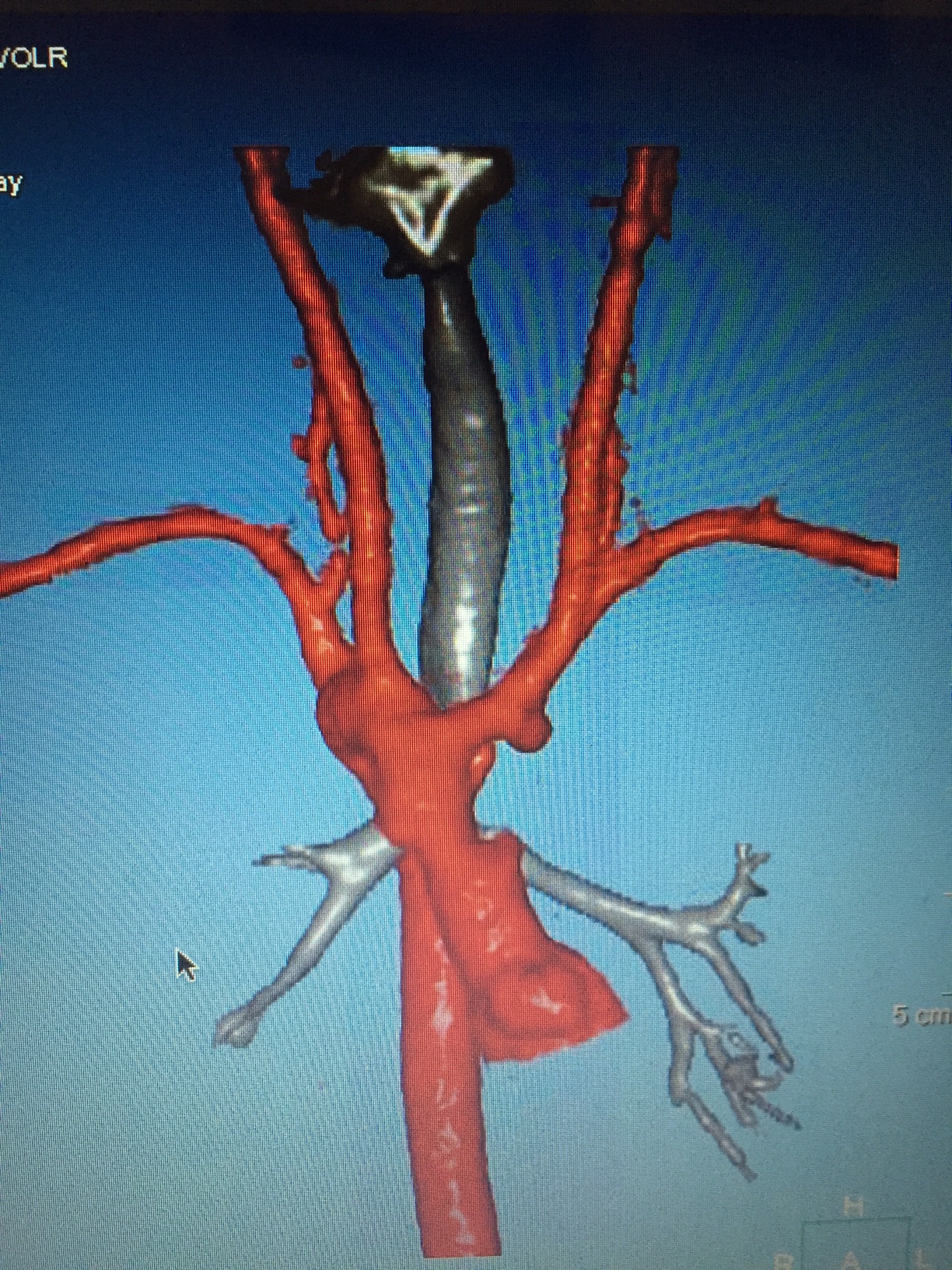

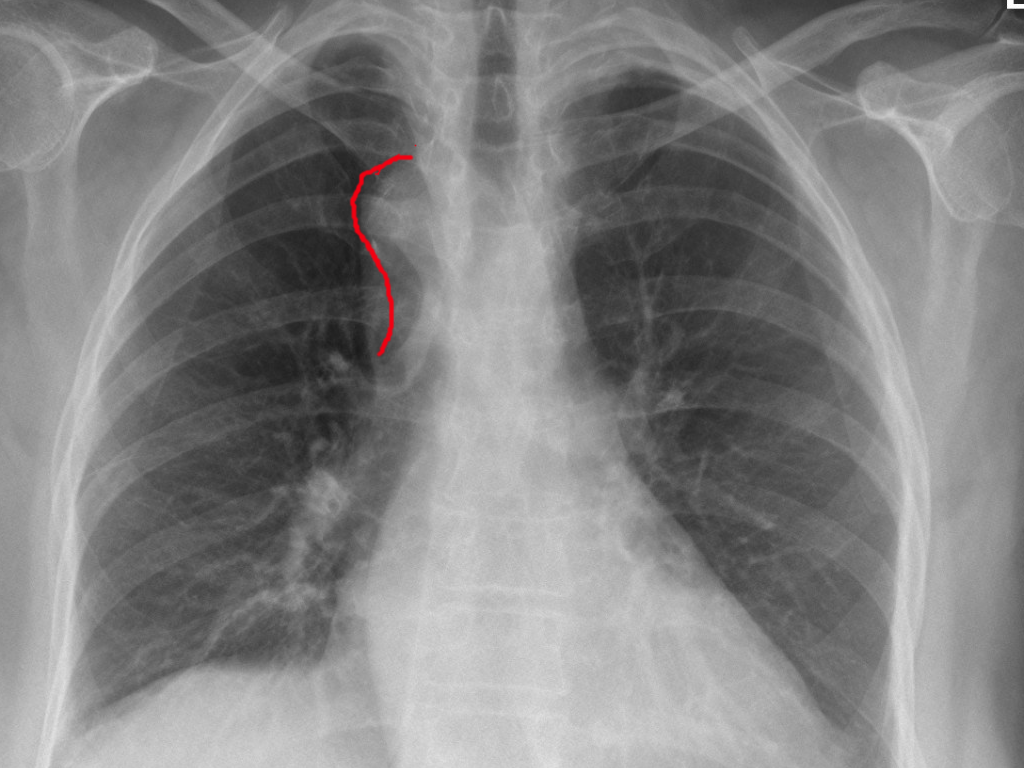

A chest x-ray can demonstrate the trachea deviated to the left in the presence of a right aortic arch. This occurs from the aortic arch crossing over the right bronchus instead of the more common right-sided deviation from a left-sided aortic arch. A barium swallow evaluation can demonstrate a posterior esophageal indentation from the aberrant left subclavian in patients with a vascular ring. An echocardiogram evaluation will demonstrate any associated intracardiac abnormalities and can demonstrate arch sidedness, including the anatomy of the arch. By echocardiography, the first branch of the aorta defines the sidedness of the aortic arch. If the first branch of the aorta bifurcates to the left, then a right aortic arch is present. CT scans can be performed when there is a concern for a vascular ring causing important symptoms. This can be helpful in preoperative surgical planning, but it should be reserved for patients in whom vascular ring surgery is considered. CT scans can also demonstrate the airway and esophagus and yield an anatomic evaluation of narrowing or compression of these structures. [12] MRI of the aorta can be performed en lieu of a CT scan to avoid a potential long-term radiation risk. Cardiac catheterization and angiography can be performed to image the aortic arch. However, due to its invasiveness, this imaging modality is reserved for patients with other congenital heart defects that require hemodynamic information of cardiac interventions.

Treatment / Management

A patient symptomatic from a right aortic arch with an aberrant right subclavian (vascular ring) can undergo surgical division of the ligamentum arteriosus with plication of the diverticulum of Kommerell off of the esophagus. If stridor secondary to tracheomalacia is present, this symptom might not fully resolve immediately after surgery. Right aortic arch with mirror imaging branching does not typically require medical or surgical therapy unless an important left pulmonary abnormality is noted. In the case of left pulmonary artery stenosis, a transcatheter balloon or stent angioplasty intervention can be performed to alleviate the stenosis. In the scenario of left pulmonary artery isolation, a strategy of left pulmonary artery rehabilitation and reimplantation can be employed. Surgical treatment of a vascular ring is rarely associated with long-term morbidity. However, there is a small surgical risk of recurrent laryngeal nerve injury and vocal cord paralysis, as well as thoracic duct injury, leading to chylous pleural effusions.[13][14][15](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

When a right aortic arch is identified, it is important to be confident of the branching pattern of the aortic arch to counsel families and patients regarding the propensity to develop symptoms. In general, patients with congenital heart defects would have symptoms as a neonate or infant that would be more concerning than the symptoms associated with a vascular ring. Feeding and swallowing difficulties in children would be more commonly associated with reflux. Respiratory symptoms, which are less common with a right aortic arch, would be common in asthma, croup, or laryngomalacia.

Consultations

When a vascular ring is suspected, pediatric cardiology and pediatric cardiovascular surgery consultation is advised.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with right aortic and mirror-image branching should be counseled that this is a benign entity. Vascular rings rarely have important respiratory symptoms, and treatment is usually advised to improve swallowing symptoms.

Pearls and Other Issues

In general, the isolated right aortic arch is a benign lesion. Right aortic arch and left pulmonary artery anomalies are more difficult to identify and may require more extensive evaluation and intervention. Vascular rings associated with right aortic arch anomalies are intervened upon for symptomatic benefit. Failure to identify a patient with a 22q11 deletion or DiGeorge syndrome can place the patient at risk for unrecognized hypocalcemia, development delay, or other future non-cardiac problems.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Evaluation and management of the patient with a symptomatic vascular ring require an interprofessional approach. Evaluation is often performed in the symptomatic patient by gastroenterology, cardiology, and otolaryngology. Repair is performed by cardiovascular surgery. Limited but specialized postoperative ICU is useful to recognize the rare complications that can occur immediately following surgery.

Media

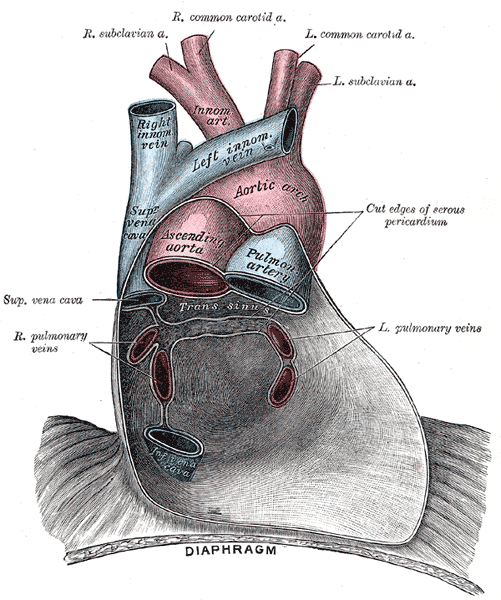

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Pericardium anatomy, Right Subclavian Artery, Right Common Carotid Artery, Left Common Carotid Artery, Left Subclavian Artery, Innominate Artery, Right Innominate vein, Left innominate vein, Aortic Arch, Superior Vena cava, Ascending Aorta, Pulmonary Artery, Left and Right Pulmonary veins, Inferior Vena Cava, Diaphragm

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

McElhinney DB, Hoydu AK, Gaynor JW, Spray TL, Goldmuntz E, Weinberg PM. Patterns of right aortic arch and mirror-image branching of the brachiocephalic vessels without associated anomalies. Pediatric cardiology. 2001 Jul-Aug:22(4):285-91 [PubMed PMID: 11455394]

Evans WN, Acherman RJ, Berthoty D, Mayman GA, Ciccolo ML, Carrillo SA, Restrepo H. Right aortic arch with situs solitus. Congenital heart disease. 2018 Jul:13(4):624-627. doi: 10.1111/chd.12623. Epub 2018 Jul 22 [PubMed PMID: 30033669]

Stern SJ, Wadekar N, Mertens L, Manlhiot C, McCrindle BW, Jaeggi ET, Nield LE. The impact of not having a ductus arteriosus on clinical outcomes in foetuses diagnosed with tetralogy of Fallot. Cardiology in the young. 2015 Apr:25(4):684-92. doi: 10.1017/S1047951114000638. Epub 2014 Apr 28 [PubMed PMID: 24775715]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNakano K, Hayashi T, Ono H. Vascular ring associated with d-transposition of the great arteries: when should we suspect aortic arch anomalies? Cardiology in the young. 2018 Dec:28(12):1489-1490. doi: 10.1017/S1047951118001610. Epub 2018 Sep 17 [PubMed PMID: 30221608]

Altun G, Babaoğlu K, Oğuz D, Dönmez M. Crossed pulmonary arteries associated with persistent truncus arteriosus and right aortic arch on the three-dimensional computed tomographic imaging. Anadolu kardiyoloji dergisi : AKD = the Anatolian journal of cardiology. 2013 Aug 5:13(5):E29. doi: 10.5152/akd.2013.164. Epub 2013 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 23728269]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePriya S, Thomas R, Nagpal P, Sharma A, Steigner M. Congenital anomalies of the aortic arch. Cardiovascular diagnosis and therapy. 2018 Apr:8(Suppl 1):S26-S44. doi: 10.21037/cdt.2017.10.15. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29850417]

Goldbach A, Dass C, Surapaneni K. Aberrant Right Vertebral Artery with a Diverticulum of Kommerell: Review of a Rare Aortic Arch Anomaly. Journal of radiology case reports. 2018 May:12(5):19-26. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v12i5.3239. Epub 2018 May 31 [PubMed PMID: 30651910]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLi S, Wen H, Liang M, Luo D, Qin Y, Liao Y, Ouyang S, Bi J, Tian X, Norwitz ER, Luo G. Congenital abnormalities of the aortic arch: revisiting the 1964 Stewart classification. Cardiovascular pathology : the official journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Pathology. 2019 Mar-Apr:39():38-50. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2018.11.004. Epub 2018 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 30623879]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceQiu Y, Wu X, Zhuang Z, Li X, Zhu L, Huang C, Zhuang H, Ma M, Ye F, Chen J, Wu Z, Yu X, An M, Chen R, Chen J, Guan L, Sang H, Ye Y, Han Y, Chen Z, Qin H, Zhu H, Zhou Y, Zilundu PLM, Xu D, Zhou L. Anatomical variations of the aortic arch branches in a sample of Chinese cadavers: embryological basis and literature review. Interactive cardiovascular and thoracic surgery. 2019 Apr 1:28(4):622-628. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivy296. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30445440]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceArakoni R, Merrill R, Simon EL. Foreign body sensation: A rare case of dysphagia lusoria in a healthy female. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2018 Nov:36(11):2134.e1-2134.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.08.029. Epub 2018 Aug 8 [PubMed PMID: 30194019]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOuedraogo AR, Boncoungou K, Maïga S, Ouedraogo G, Badoum G, Diallo O, Bonkoungou G, Nacanabo R, Ouedraogo M. [A case of malformation of aortic arches simulating asthma]. Revue de pneumologie clinique. 2018 Sep:74(4):253-256. doi: 10.1016/j.pneumo.2018.03.002. Epub 2018 Jul 17 [PubMed PMID: 30017752]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMuller CO, Derycke L, Kheniche A, Garcia G, Bernard S, Teissier N, Bonnard A. Routine multi detector computed tomography evaluation of tracheal impairment compared to laryngo-tracheal endoscopy in children with vascular ring. Pediatric surgery international. 2018 Aug:34(8):879-884. doi: 10.1007/s00383-018-4279-4. Epub 2018 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 29961107]

Slater BJ, Rothenberg SS. Thoracoscopic Management of Patent Ductus Arteriosus and Vascular Rings in Infants and Children. Journal of laparoendoscopic & advanced surgical techniques. Part A. 2016 Jan:26(1):66-9. doi: 10.1089/lap.2015.0126. Epub 2015 Aug 27 [PubMed PMID: 26312644]

Burke RP, Wernovsky G, van der Velde M, Hansen D, Castaneda AR. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for congenital heart disease. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 1995 Mar:109(3):499-507; discussion 508 [PubMed PMID: 7877311]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBidar E, Arrigoni SC, Accord RE. Resection of Kommerell Diverticulum and Reimplantation of Aberrant Left Subclavian Artery in Right Aortic Arch Vascular Ring. Seminars in thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2019 Autumn:31(3):561-563. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2018.11.015. Epub 2018 Dec 7 [PubMed PMID: 30529160]